log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

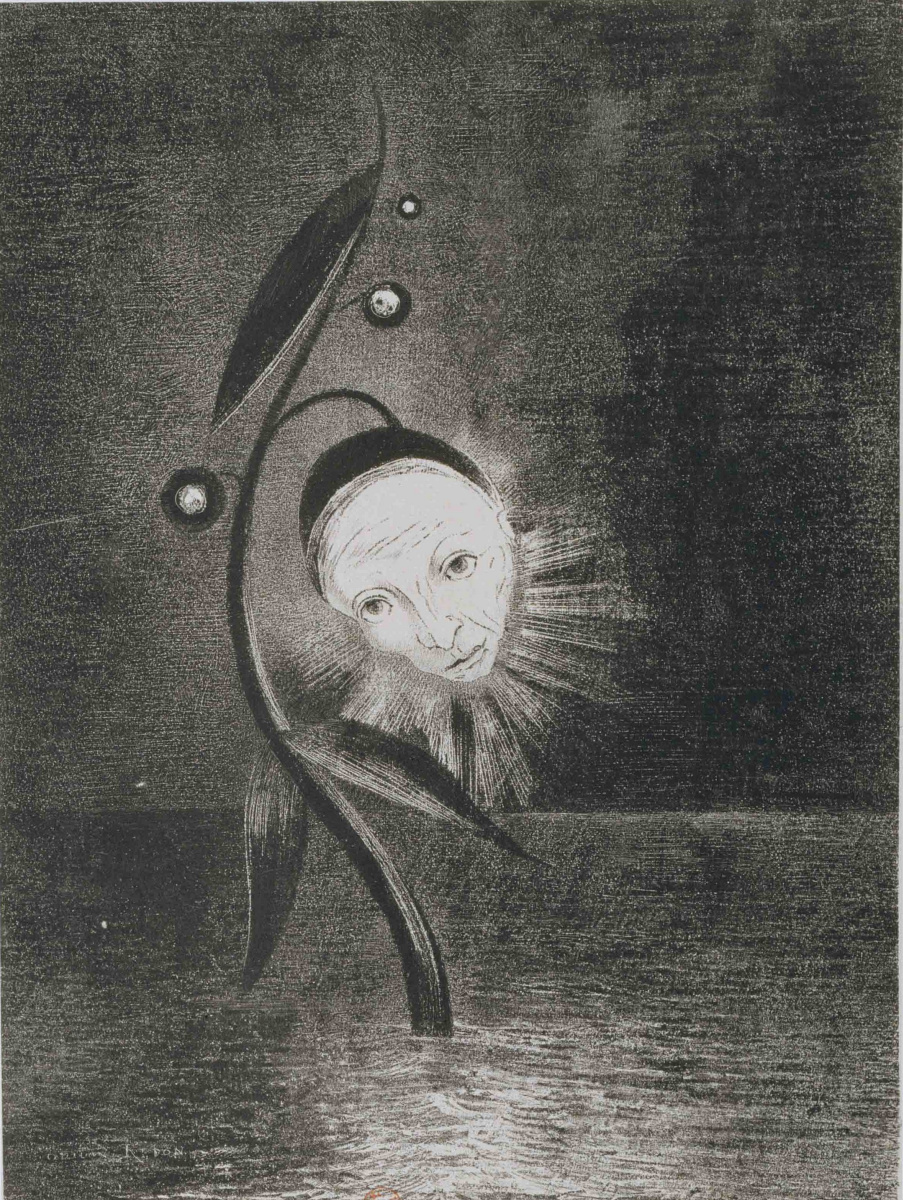

The Marsh Flower, a Sad Human Head

Odilon Redon • Painting, 1885, 27.5×20.5 cm

Description of the artwork «The Marsh Flower, a Sad Human Head»

Pop culture of the 20th and 21st centuries subjected the viewers to such a diverse range of frightening images that it would seem strange to be afraid of smiling spiders or floating winged heads which the artist drew in the 19th century. But the fact is that Odilon Redon had no intention of frightening anyone. Above all things, those mysterious images born of imagination were Redon's way of learning the world and being a part of it. And that world moved beyond the present and visible space. Redon went deep – to where everything began and everything was possible. To where the world was born out of chaos, was versatile, tried on bizarre forms and probed endless variants of viable creatures and phenomena.

Redon saw little point in depicting reality. And yet, he was obsessed with a meticulous, almost scientific study of its small, minor components. He drew blades of grass, stones and pieces of peeling plaster on the old wall – and created a vast catalogue of patterns used by nature in its craft. Studying at the architectural school, a long friendship with the well-known and enthusiastic botanist Armand Clavaud, his own solitary walks in the thickets and forests provided Redon with the understanding of "visual logic" – he was getting a better grasp of how an imaginary image should be depicted in order to be perceived as a real one. His monsters look as if they were created by nature itself. And that realness, consistency, and even casualness of Redon's monsters is scarier than zombies rising from the dead and spitting green slime or ghosts of little girls from another horror movie, squeezing adrenaline from its viewers.

"My originality consists in bringing to life, in a human way, improbable beings and making them live according to the laws of probability, by putting – as far as possible – the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible," said Redon.

The lithography Marsh Flower belongs to the Homage to Goya series, which Redon released in 1885 in an edition of 50 copies (the later second edition included 25 copies). The album consisted of only 6 lithographs not sharing any common symbolic meaning or philosophical maxim. Except that one ingenious visionary was inspired by the bizarre fantasies of the other one. Here’s a head of a wise goddess brought by the morning drowse – her hair is full of accessories, or fragments of ancient rocks, or the fused shells of prehistoric oceanic molluscs. And here we've got the creatures-embryos of the plainest shape, but with frightfully sad, tired eyes: they must have been waiting to be born for a thousand years. A madman in the midst of an extinct, withered landscape. Still, The Marsh Flower is the scariest lithography of the series, since here the invisible with all the visual logic becomes visible.

The endless marsh touches the horizon – it's either the world before the birth of the land, or the one where the firm ground is not conceived by the creator. The flower with a human face, in which, without much effort, it is possible to see a bizarre anatomy, either that of a vegetable, or a human: veins-stems, blood-juice, sharp wrinkles, foreshadowing the rapid withering, inner shining, which turns out to be the only possible action. And embryonic buds ripening in transparent cocoons, which are awaited by the same contemplative stillness and infinitely long growing-up in the world where land is not conceived. In the world where there's nothing else to see except the marsh. In the world where you are sure to ripen and illuminate this impenetrable depth of muddy water.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Redon saw little point in depicting reality. And yet, he was obsessed with a meticulous, almost scientific study of its small, minor components. He drew blades of grass, stones and pieces of peeling plaster on the old wall – and created a vast catalogue of patterns used by nature in its craft. Studying at the architectural school, a long friendship with the well-known and enthusiastic botanist Armand Clavaud, his own solitary walks in the thickets and forests provided Redon with the understanding of "visual logic" – he was getting a better grasp of how an imaginary image should be depicted in order to be perceived as a real one. His monsters look as if they were created by nature itself. And that realness, consistency, and even casualness of Redon's monsters is scarier than zombies rising from the dead and spitting green slime or ghosts of little girls from another horror movie, squeezing adrenaline from its viewers.

"My originality consists in bringing to life, in a human way, improbable beings and making them live according to the laws of probability, by putting – as far as possible – the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible," said Redon.

The lithography Marsh Flower belongs to the Homage to Goya series, which Redon released in 1885 in an edition of 50 copies (the later second edition included 25 copies). The album consisted of only 6 lithographs not sharing any common symbolic meaning or philosophical maxim. Except that one ingenious visionary was inspired by the bizarre fantasies of the other one. Here’s a head of a wise goddess brought by the morning drowse – her hair is full of accessories, or fragments of ancient rocks, or the fused shells of prehistoric oceanic molluscs. And here we've got the creatures-embryos of the plainest shape, but with frightfully sad, tired eyes: they must have been waiting to be born for a thousand years. A madman in the midst of an extinct, withered landscape. Still, The Marsh Flower is the scariest lithography of the series, since here the invisible with all the visual logic becomes visible.

The endless marsh touches the horizon – it's either the world before the birth of the land, or the one where the firm ground is not conceived by the creator. The flower with a human face, in which, without much effort, it is possible to see a bizarre anatomy, either that of a vegetable, or a human: veins-stems, blood-juice, sharp wrinkles, foreshadowing the rapid withering, inner shining, which turns out to be the only possible action. And embryonic buds ripening in transparent cocoons, which are awaited by the same contemplative stillness and infinitely long growing-up in the world where land is not conceived. In the world where there's nothing else to see except the marsh. In the world where you are sure to ripen and illuminate this impenetrable depth of muddy water.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova