log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

Reptiles

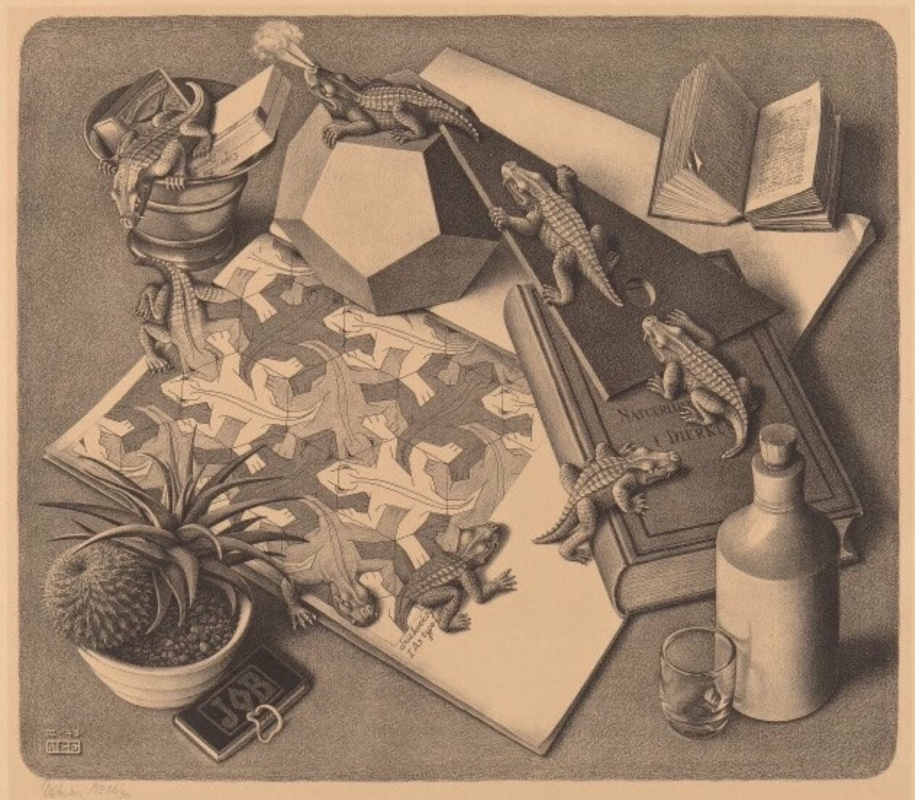

Maurits Cornelis Escher • Graphics, 1943, 33.4×38.7 cm

Description of the artwork «Reptiles»

Maurits Escher is a Belgian graphic artist who is most famous for his works with the “impossible” constructions and unusual ornaments. The impetus for the creation of the latter ones was the artist’s journey to Spain. Seeing the Moorish mosaics of the Alhambra in 1936, he did not just set out to “make them alive”. The artist wrote: “What a pity that the Islamic prohibition to depict ‘idols’ limited the masters to a variety of patterns of an abstract geometric type... to make decorative elements of specific, recognizable, naturalistic forms of fish, birds, snakes or people.” This is exactly what Escher did by bringing some game elements into the logical constructions of his original image gallery. But he did not confine himself to the purely artistic introduction of the living world into the mosaic environment.

With the help of “game” methods, the former boy, who once tightly docked small pieces of cheese on a sandwich, now being a serious man, an artist gaining his fame, solved design, geometric and philosophical problems. At the same time, Maurits, kind of a cold fish and a pedant, who nurtured every engraving with the precision and diligence of a jeweller, did not lose his truly childish fervour, passion and invention.

Thus, to create the Reptiles engraving, a 45-year-old master made a plasticine figurine of a lizard and moved it around the table. Moreover, he was by no means a neophyte in composing elements: the interweaving creatures, their transitions into each other began to appear in his work from the end of the 1930s: in 1938, Escher created an engraving with birds, which formed the basis of his iconic artwork Day and Night. Note, it is 1943, the Netherlands was occupied by German troops. Escher, who would soon save the artistic legacy of a Jewish teacher who died in a concentration camp, and after the war would take part in an exhibition of artists who refused to cooperate with the Nazis, sculpted plasticine figurines and solved artistic problems.

That time the idea was as follows: “…the transition from plane to space and vice versa. On the one hand, a frozen whole of plane elements comes to life; on the other hand, independent individuals weaken and dissolve in the mass. A series of identical three-dimensional beings... often emerge as a single individual in motion. This is a static method of illustrating the motion dynamics.”

The artist visualized the idea very vividly. This is how Escher described one of his most famous works, considering it one of the best among the hundreds of his subjects. “On the table, among other things, is a sketchbook; on the open page we can see a mosaic of zoomorphic forms in three contrasting shades. As you can see, one amphibian is tired of lying sprawled next to the same companions, therefore it lowers its front, like a plastic foot from the edge of a book, scarcely frees itself from the two-dimension world and enters the real life. It crawls onto the thick binding of the zoological book and makes the hard way up the slippery slope of the drawing square to the highest point of its existence (the hexagon platform). Sneezing briefly, tired but contented, it crawls over the ashtray, and goes down to its original place — onto a flat sheet of sketchbook, and resignedly joins its friends, regaining its function of a surface dividing element.”

As you can see, three-dimensionality is a rebellion of a living creature, plane is limitations and frames, submission of a two-dimensional image for a thinker artist. On this sublime note, the story of the remarkable artwork of the graphic paradox praiser, the philosopher and the original creator could have been completed, if not for his own remark from the description of the engraving. “Note. The little book that says ‘JOB’ has nothing to do with the Bible: JOB is a brand of Belgian cigarette paper.” This is the prose of life, and art is an organic component of the world of things. As Escher saw it.

Author: Olha Potekhina

With the help of “game” methods, the former boy, who once tightly docked small pieces of cheese on a sandwich, now being a serious man, an artist gaining his fame, solved design, geometric and philosophical problems. At the same time, Maurits, kind of a cold fish and a pedant, who nurtured every engraving with the precision and diligence of a jeweller, did not lose his truly childish fervour, passion and invention.

Thus, to create the Reptiles engraving, a 45-year-old master made a plasticine figurine of a lizard and moved it around the table. Moreover, he was by no means a neophyte in composing elements: the interweaving creatures, their transitions into each other began to appear in his work from the end of the 1930s: in 1938, Escher created an engraving with birds, which formed the basis of his iconic artwork Day and Night. Note, it is 1943, the Netherlands was occupied by German troops. Escher, who would soon save the artistic legacy of a Jewish teacher who died in a concentration camp, and after the war would take part in an exhibition of artists who refused to cooperate with the Nazis, sculpted plasticine figurines and solved artistic problems.

That time the idea was as follows: “…the transition from plane to space and vice versa. On the one hand, a frozen whole of plane elements comes to life; on the other hand, independent individuals weaken and dissolve in the mass. A series of identical three-dimensional beings... often emerge as a single individual in motion. This is a static method of illustrating the motion dynamics.”

The artist visualized the idea very vividly. This is how Escher described one of his most famous works, considering it one of the best among the hundreds of his subjects. “On the table, among other things, is a sketchbook; on the open page we can see a mosaic of zoomorphic forms in three contrasting shades. As you can see, one amphibian is tired of lying sprawled next to the same companions, therefore it lowers its front, like a plastic foot from the edge of a book, scarcely frees itself from the two-dimension world and enters the real life. It crawls onto the thick binding of the zoological book and makes the hard way up the slippery slope of the drawing square to the highest point of its existence (the hexagon platform). Sneezing briefly, tired but contented, it crawls over the ashtray, and goes down to its original place — onto a flat sheet of sketchbook, and resignedly joins its friends, regaining its function of a surface dividing element.”

As you can see, three-dimensionality is a rebellion of a living creature, plane is limitations and frames, submission of a two-dimensional image for a thinker artist. On this sublime note, the story of the remarkable artwork of the graphic paradox praiser, the philosopher and the original creator could have been completed, if not for his own remark from the description of the engraving. “Note. The little book that says ‘JOB’ has nothing to do with the Bible: JOB is a brand of Belgian cigarette paper.” This is the prose of life, and art is an organic component of the world of things. As Escher saw it.

Author: Olha Potekhina