log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

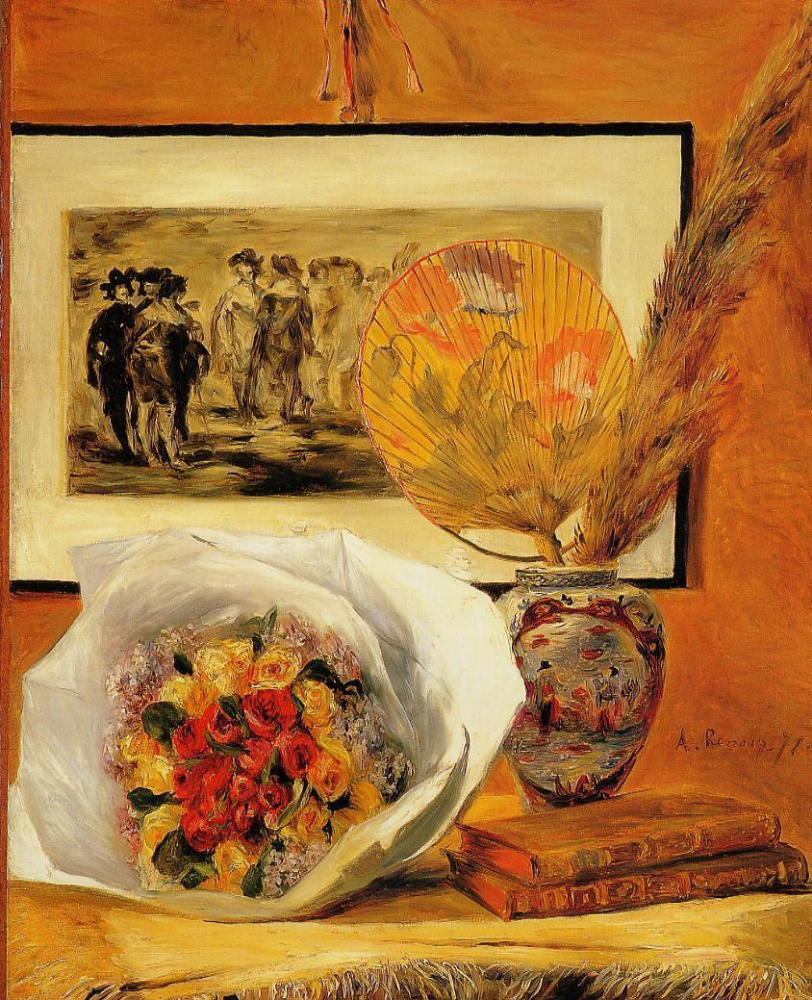

Still life with bouquet

Pierre-Auguste Renoir • Painting, 1871, 73.7×59.8 cm

Description of the artwork «Still life with bouquet»

“If I sold only good pictures, I would starve to death,” Renoir joked. He painted still lifes just to survive. They sold well and were easy to create. Renoir rested, when he painted freshly picked flowers, as other people relax, when they dance or drink wine. However, this still life is special. This is a dedication still life, a confession still life to Edouard Manet.

The first reminiscence: engraving. In the background of the Renoir’s still life is an engraving for the painting, which few people know nowadays. In the 19th century, it was considered the work of Velasquez and was stored in the Louvre along with other Spanish masterpieces that got to museum halls as Napoleonic war spoils. Manet was delighted with Spain and Velázquez, he painted dozens of paintings, inspired by Spanish motives, Spanish costumes, composition and motives of Spanish artists. Now the canvas is attributed to the son-in-law of Velázquez, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo or simply the Madrid School. However, the engraving that appeared inside the Still Life with a Bouquet was definitely made by Édouard Manet.

The second reminiscence: flowers. If there was no engraving, all other items could be considered slightly far-fetched, but Renoir himself legitimized further searches for allusions. The bouquet in the scandalous Olympia painting by Édouard Manet was too big, critics did not fail to reproach the artist for the violation of proportions. However, it is impossible not to notice it: this is the semantic centre of the picture, which turns an ordinary image of a nude female nature into a very unambiguous plot: behind the bouquet, somewhere out there, in the living room, outside the door, is a man who Olympia, the naked Olympia, is about to receive. Probably, everyone remembered this bouquet: critics who splashed poisonous reproaches for indecency, and young Impressionists, who called Manet their teacher. Renoir collected a bouquet for the still life to his liking, but wrapped it in exactly the same thick white paper as in Olympia.

The third reminiscence: the fan and the books. Japan has become no less a revelation and artistic shock for the French than Spain. Compositional solutions, colour findings, drawings of Japanese prints — they all literally sprouted into Impressionism. Monet, Van Gogh, Cézanne and, of course, Renoir bought stacks of oriental landscapes in art shops, hung them on the walls, absorbed and studied. “I’m sure that Japanese landscapes are no better than others. Only one thing: Japanese artists managed to find the hidden treasure,” Renoir admired many years later. This Japan-admiring explanation could have been the full stop, if not for the books and if it not for the already set need to look for Manet. In every detail. And we can find Manet again. Two years before Renoir undertook to collect all these iconic things in one painting, Manet painted a portrait of Émile Zola at his desk. Renoir definitely saw him and grabbed a couple of books and Japanese motives from there as a keepsake. In any case, it could be so.

Written by Anna Sidelnikova

The first reminiscence: engraving. In the background of the Renoir’s still life is an engraving for the painting, which few people know nowadays. In the 19th century, it was considered the work of Velasquez and was stored in the Louvre along with other Spanish masterpieces that got to museum halls as Napoleonic war spoils. Manet was delighted with Spain and Velázquez, he painted dozens of paintings, inspired by Spanish motives, Spanish costumes, composition and motives of Spanish artists. Now the canvas is attributed to the son-in-law of Velázquez, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo or simply the Madrid School. However, the engraving that appeared inside the Still Life with a Bouquet was definitely made by Édouard Manet.

The second reminiscence: flowers. If there was no engraving, all other items could be considered slightly far-fetched, but Renoir himself legitimized further searches for allusions. The bouquet in the scandalous Olympia painting by Édouard Manet was too big, critics did not fail to reproach the artist for the violation of proportions. However, it is impossible not to notice it: this is the semantic centre of the picture, which turns an ordinary image of a nude female nature into a very unambiguous plot: behind the bouquet, somewhere out there, in the living room, outside the door, is a man who Olympia, the naked Olympia, is about to receive. Probably, everyone remembered this bouquet: critics who splashed poisonous reproaches for indecency, and young Impressionists, who called Manet their teacher. Renoir collected a bouquet for the still life to his liking, but wrapped it in exactly the same thick white paper as in Olympia.

The third reminiscence: the fan and the books. Japan has become no less a revelation and artistic shock for the French than Spain. Compositional solutions, colour findings, drawings of Japanese prints — they all literally sprouted into Impressionism. Monet, Van Gogh, Cézanne and, of course, Renoir bought stacks of oriental landscapes in art shops, hung them on the walls, absorbed and studied. “I’m sure that Japanese landscapes are no better than others. Only one thing: Japanese artists managed to find the hidden treasure,” Renoir admired many years later. This Japan-admiring explanation could have been the full stop, if not for the books and if it not for the already set need to look for Manet. In every detail. And we can find Manet again. Two years before Renoir undertook to collect all these iconic things in one painting, Manet painted a portrait of Émile Zola at his desk. Renoir definitely saw him and grabbed a couple of books and Japanese motives from there as a keepsake. In any case, it could be so.

Written by Anna Sidelnikova