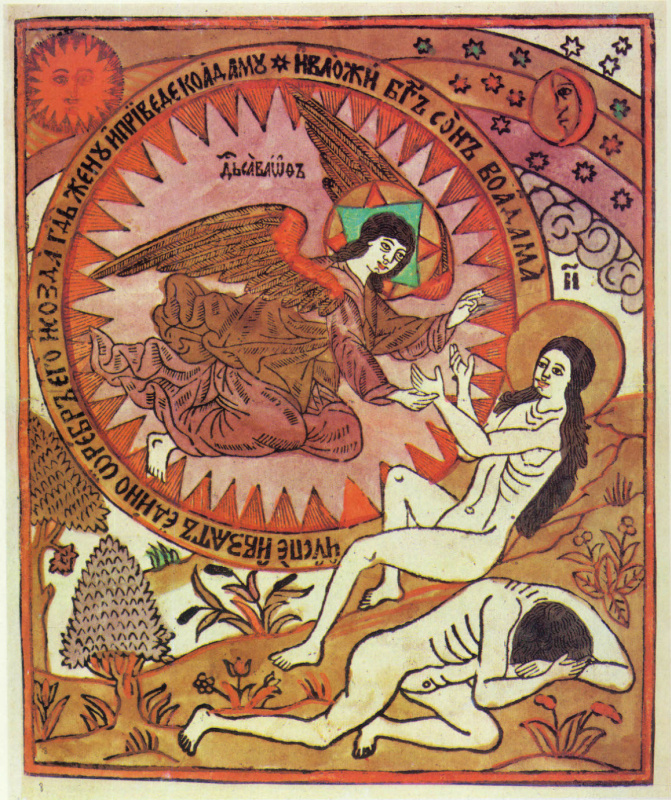

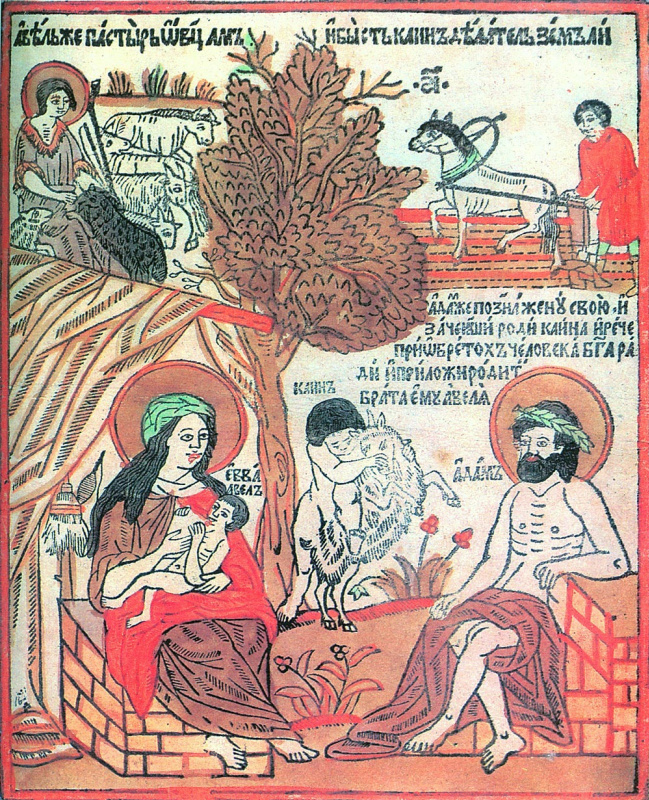

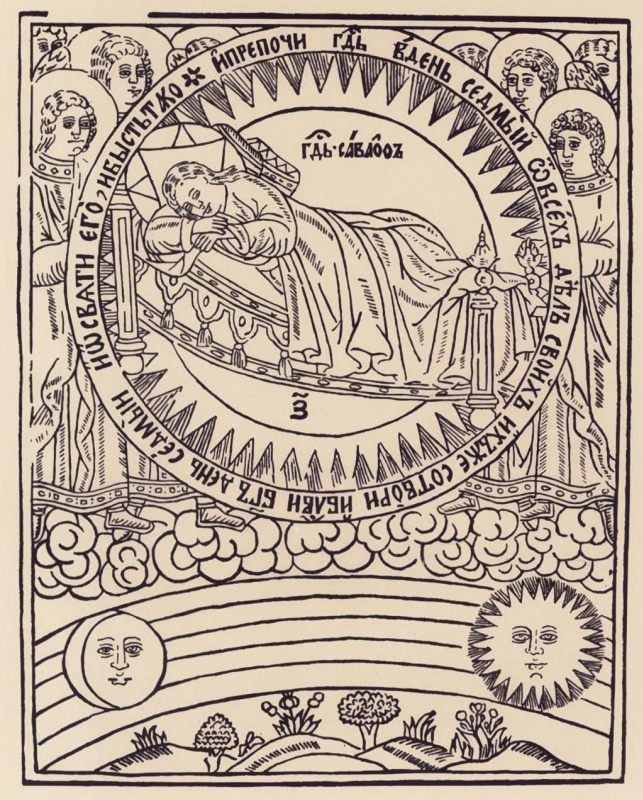

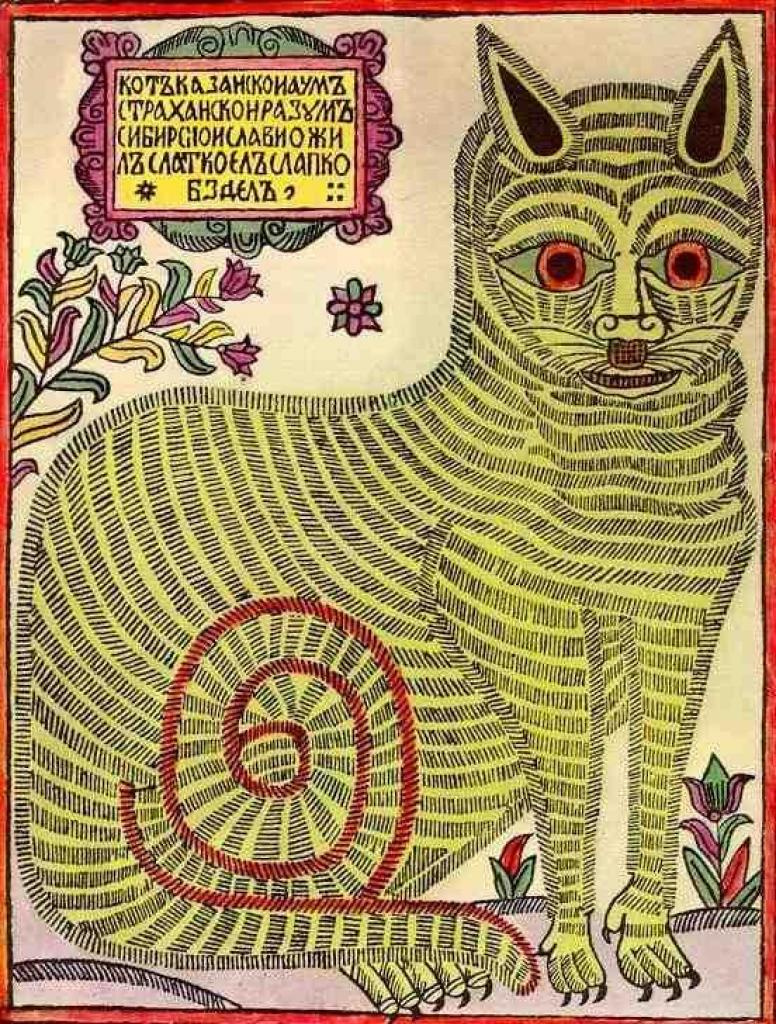

The origins of this genre are oriental outline engravings. Lubok appeared in Europe in the 15th century, and in Russia in the 17th century. It gained popularity among peasants and city dwellers. Its authors were real masters of both epithets, illustration, and caricature. Vivid pictures with simple figures and simple, often humorous, captions are an example of the Russian folk artists' product, which brought a lot of joy to inexperienced customers. The lubok prints were made using carved wooden clichés, which were used to make prints on sheets of inexpensive paper. Over time, the outline drawings of these engravings were partially painted with bright colours, which made them more expressive and attractive.

The history of contour engravings is quite old. In China, they only started to print them in the 8th century, and until that time popular pictures had been painted by hand. In India, the painted contour drawings were often part of Buddhist cult. Tibetan artists created their painted miniatures called tsakli, which were used in the Buddhist prayer tradition.

Hayagriva Tsakli, Tibet. 13—14th cent. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Luboks only appeared in Europe in the 15th century; they were made using the woodcut

. Simple pictures and texts allowed, as they say, "enlighten the masses," and the Bible for the poor (Latin Biblia Pauperum) became one of the striking examples. The first such publication was printed in German in 1462; it appeared thanks to Christian preachers. They rightly believed that the pictures featuring the scenes from the Holy Scriptures give the illiterate parishioners greater visibility in studying the Bible. Short accompanying texts were written not in Latin, but in the language of the country for which the book was printed. By the end of the 15th century, the Biblia Pauperum for the poor was also printed in the Netherlands.

Due to its simple and intelligible form — pictures with short captions — as well as the simplicity of its copying, lubok as a kind of medieval leaflet has become a way of influencing the broad masses. Similar prints were used during the Peasant War in Germany, during the French Revolution. In fact, lubok became the progenitor of propaganda posters, and the subjects of humorous images became the prerequisites for the birth of the caricature genre.

This caricature of the time of the French Revolution (1789) depicts the "third estate", which included the middle class, merchants and peasants, who carry two privileged classes — the nobility and priests.

By the end of the 17th century, in the Moscow Vegetable Row, as well as in the shops of the Spassky Bridge, one could buy the so-called "German amusing sheets", which were printed on a special machine in the court printing house. But soon "the sheets printed by some Germans heretics, luthers and calvines" were banned by the clergy, who, in addition, were categorically against the replication of the faces of Christ. Permission to print lubok was issued by the Izugraf Chamber, but soon these restrictions began to be ignored. In the mid-18th century, the approval of the layouts for printing paper icons was entrusted to the diocesan bishops. In 1822, the print of lubok was subjected to police censorship.

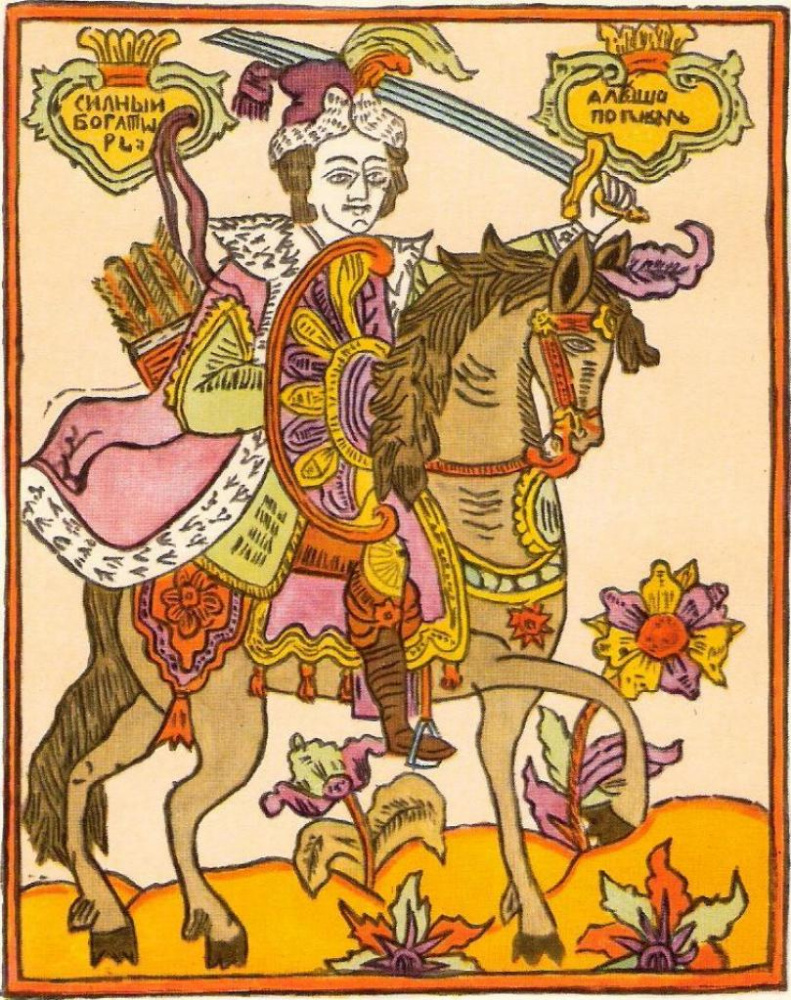

Lubok with the image of Alyosha Popovich. 18th century

Citizens and peasants willingly bought inexpensive bright goods — fairy tales and parables, historical and biblical stories, instructive drawings on vicious addictions such as drunkenness or greed, illustrations for famous folk songs, pictures with pretty young ladies and city views. The cheapest example of print art cost half a kopeck, and a beautifully painted picture with many details could cost twenty-five kopecks.

A bear and a goat cooling off. Lubok, 18th century

Probably, these simple pictures got their name from the thin layer of wood — bast (lub), which was separated from the inside of the linden bark when barking this tree. Flat and thin strips of bast were used for weaving bags and boxes, making bast covers and shoes, and also they were used instead of paper. According to another version, since linden wood was one of the favourite materials for carving, pictures created after linden clichés were called by its name. Another name for popular prints — "prostovik" — reflected their purpose for the simple; perhaps it meant the simplicity and clearness of the images depicted on the luboks.

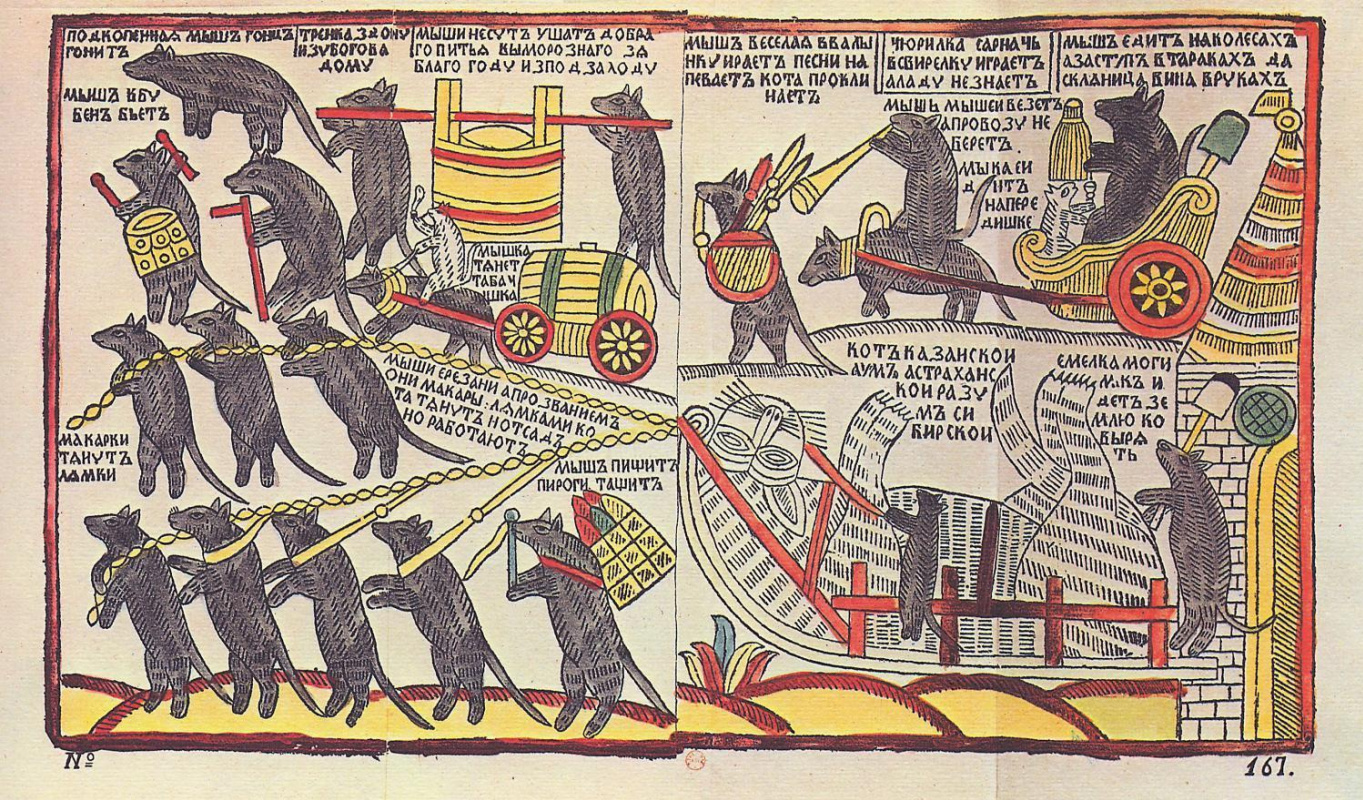

Unknown Russian artist. The Mice are burying the Cat. 1760

The lubok contours were printed on the so-called "fryazhskiye machines" from carved wooden boards. At one of the first Akhmetovs lubok printing factories, 20 machines worked. Ready-made black-and-white pictures were taken to artels, where they were painted manually by colourists. With the invention of the steam printing press, colour printing appeared, and the prints became even more massive: they began to be printed lithographically. By the end of the 19th century, Moscow printing houses of Sytin, Morozov, Chizhov and many other publishers printed about 4 million luboks annually.

"The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish. By the very pledge of the blue sea lived an old man and his old woman…"

(translated by Robert Chandler)

Moscow, P. I. Orekhov Typo-Lithography. 1878

Luboks were often printed in series, which is of great interest to historians of folk life. These drawings are a very interesting source for studying the customs, fashion and everyday life of people, as well as the growth of the artistic skill of the engravers who made the boards, and later copper clichés from which the luboks were printed.

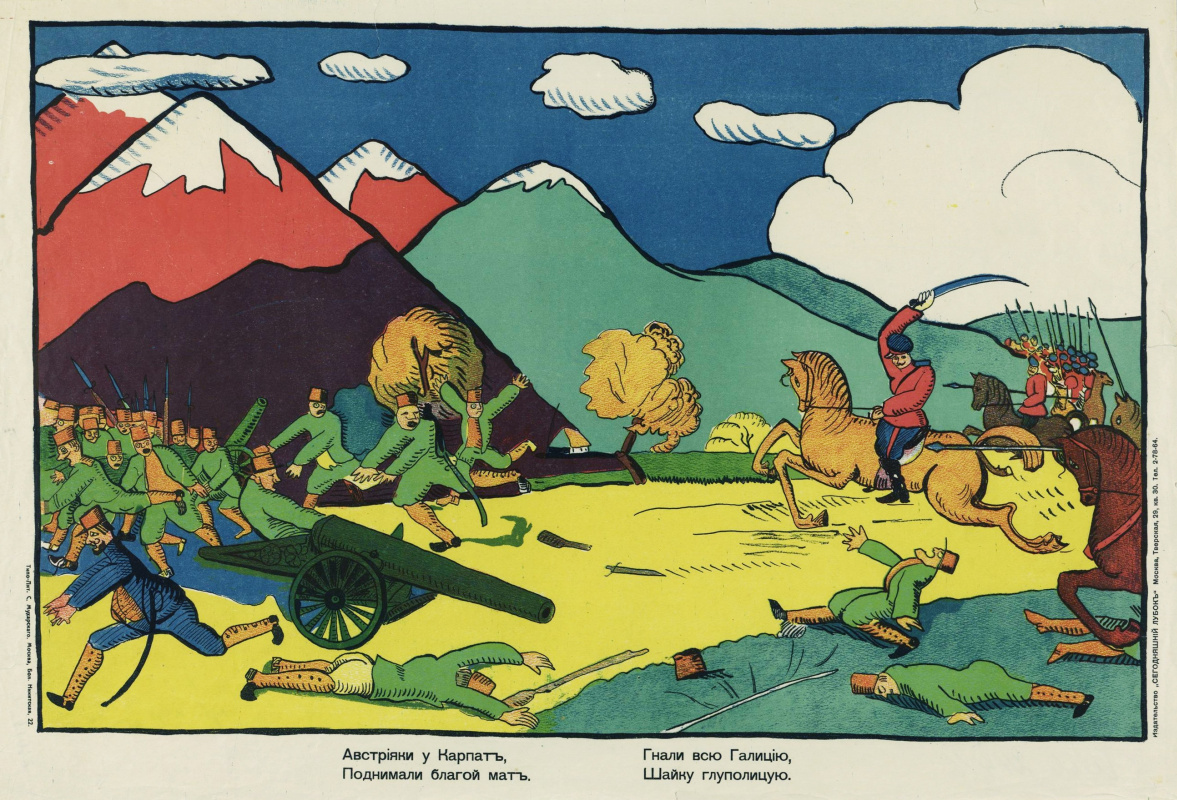

The Austrian went to Radziwill...

1914, 32.8×49.5 cm

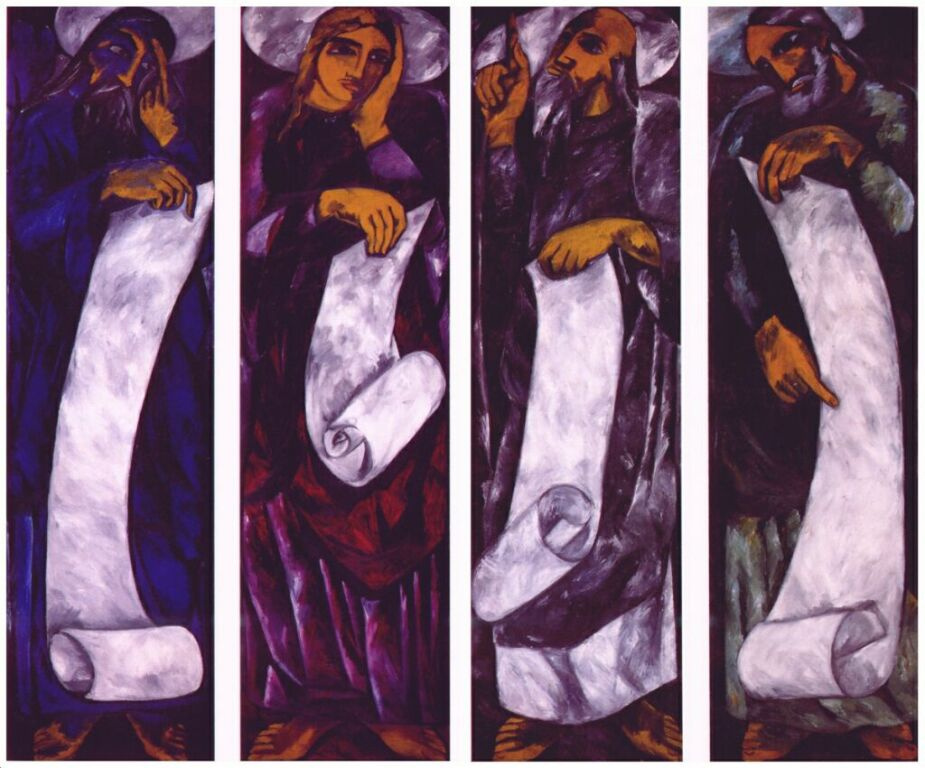

Many Russian artists turned to folk art of lubok, including illustrator Ivan Bilibin. The "peasant" theme and primitive folk art often appeared in popular prints and textile patterns by Russian avant-garde

artists. Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky worked in the genre of lubok. Natalia Goncharova constantly used lubok in her works, and her husband, Mikhail Larionov, was a passionate collector of lubok. As the artist Pavel Mansurov recalled, "most of all they wandered around the bazaars with Kandinsky, looking for peasant luboks. Bova Korolevich and Tsar Saltan with the angels and archangels, thoroughly covered with aniline — this, and not Cézanne, was the source of all the beginnings."

The four evangelists

1911

In the autumn of 1914, Today’s Lubok Publishing House was created, whose task was to create postcards to raise the morale of Russian soldiers. In total, the publishing house issued 42 popular lubok postcards by such artists as Ilya Mashkov, David Burliuk, Kazimir Malevich, Aristarkh Lentulov, Vasily Chekrygin and Vladimir Mayakovsky, who also wrote some of the poem texts.

Today’s Lubok. Postcard "Austrians near the Carpathians shout at the top of their voice". 1914. Source

The senator, legal scholar and art critic Dmitry Alexandrovich Rovinsky (1824−1895) investigated Russian lubok most deeply. He published 19 scientific works, including "The History of Russian Iconography Schools", "Materials for Russian Iconography", as well as "The Detailed Dictionary of Russian Engraved Portraits". Dmitry Rovinsky devoted his Russian Folk Pictures nine-volume edition to the history of lubok, which includes four atlases, the most comprehensive study

of this genre to date.