Start the engine!

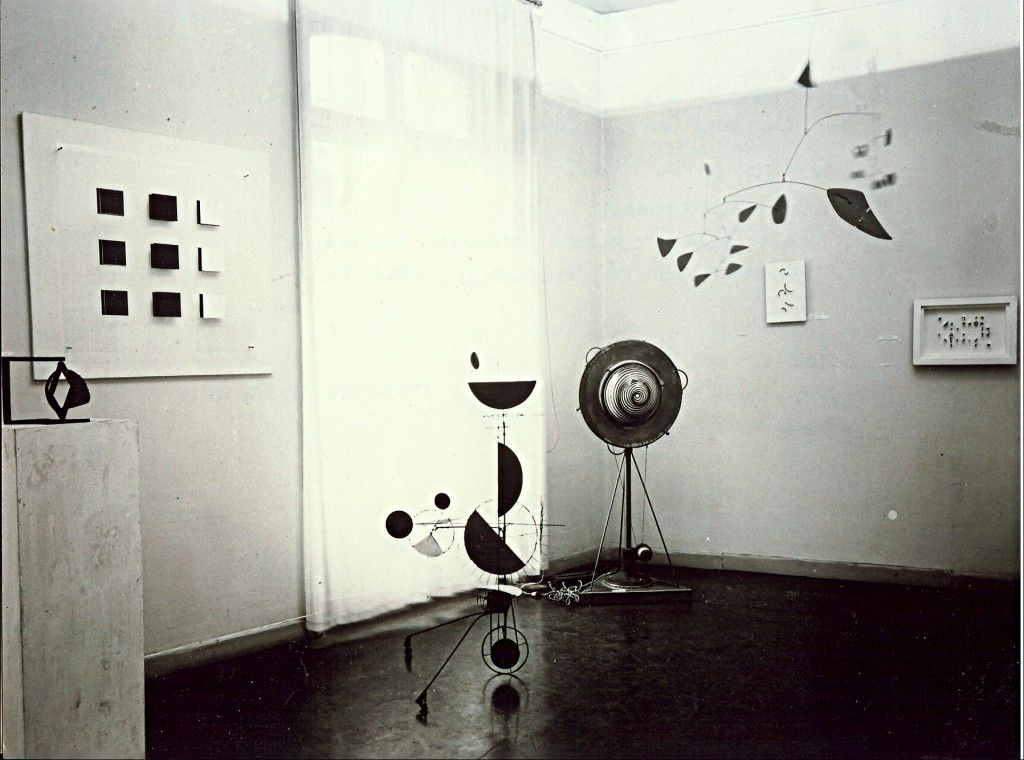

Though as early as in the 1930s, Dada and Constructivist sculptors attempted to create moving art objects, it was only in 1955 that kinetic art started being spoken of as an artistic style in its own right. That year, the Galerie Denise René in Paris held an exhibition named Le Mouvement ("The Motion"). It brought together works by Avant-garde artists from different countries who, in a variety of ways, aimed to work their way through the immobility, the stillness of an art object, its once-and-forever "museumness." The exhibitors were allowed to do anything they found necessary: they could suspend their works from the ceiling, set them drifting and rolling about the exhibition floor, confuse and perplex the public with optical illusions. The public, in turn, were allowed to approach the art pieces, touch them, breathe on them, wind them up, and play with them. Actually, Denise René had no intention to announce a new artistic movement. For a year, she had been keeping track of whatever interesting had taken place in Paris, and now, she just got the prominent artists all together.

What the hell were they thinking of!

Why was kinetic art so persistently opposed to abstract Expressionism ? What alternatives could it offer to the huge abstract canvases that had made New York a centre of modern art of that time? During centuries, Paris had got accustomed to being the artistic Mecca for the whole world, and now, it was not going to give up this title to New York that easily.The abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning rejected figurativeness and imagery to focus on their inner life and personal experience. Kinetic artists, as if indirectly arguing with them, persisted in taking a firm hold of the real world that could be felt, heard, analysed, modelled, and calculated. The mid-20th-century reality had a certain order of things they could not ignore.

1. Rapid scientific and technical development. Since Einstein’s discoveries, the relation between time and space had no longer been a purely scientific question. Now, it had become an object for artistic study , a matter to reflect upon by means of art. It was hardly an accident that Alexander Calder and Naum Gabo, the progenitors of kinetic art, were educated as engineers. In Munich, Gabo was even Einstein’s student, and Calder had an engineering experience in the car industry and on a passenger ship.

3. Nobody was sure of anything any longer. The future had discredited itself, and the past was disastrous. In 1959, Jean Tinguely took a flight in an aeroplane over Düsseldorf, and scattered 150,000 leaflets with his artistic manifesto: one should live in the present, and the only thing which is constant and stable, the only reality available is movement.

An engineering project or a scrap heap monster?

Like any artistic trend, kinetic art did not appear out of thin air, all of a sudden. Prior to the legendary exhibition in the Galerie Denise René, absolutely different artists from different cities and countries, motivated by different ideas and outlooks, quite independently, built up moving constructions. Many of them were Constructivist artists. They greeted every technical innovation, never hesitated to apply them in their creations, and advocated the unity of art, science, and technology. There were also Dada painters, who derided the very idea that an artwork could be of any use. Besides, they sneered at people’s state of bondage to modern technologies, that is why they composed absolutely useless constructions from litter and second hand machine parts.However different, even diametrically opposite were the philosophic foundations of the first kinetic experiments in art, they all paved the way for the rise of kinetic art as an independent movement in the 1960s. There were some important examples of these experiments.

It is rather a model than a finished work of art. Its creator is the avant-garde artist Vladimir Tatlin. In 1920, he designed an architectural object that was never brought into being. However, models of the building were exhibited in Moscow and Petrograd. At an International Exhibition in Paris, a model of Tatlin’s Tower won the gold medal. This metal construction was supposed to house rotating rooms of glass, shaped as a cube, a pyramid, a cylinder, and a hemisphere. The cube was to make a complete revolution in a year, the pyramid in a month, the cylinder in a day, the hemisphere in an hour.

Light-Space Modulator by László Moholy-Nagy

A Constructivist painter and professor in the progressive Bauhaus school, László Moholy-Nagy invented a machine and built it assisted by an engineer and a metalsmith. The machine was driven by an electric motor and had mobile elements fixed on its base: metal plates, perforated discs, a glass spiral, and a small ball. Lit with 130 light bulbs, the moving parts cast grotesque shadows on the walls and ceiling. The Modulator was nothing more than a means to create a moving image, and the real objective was the shadow dance.

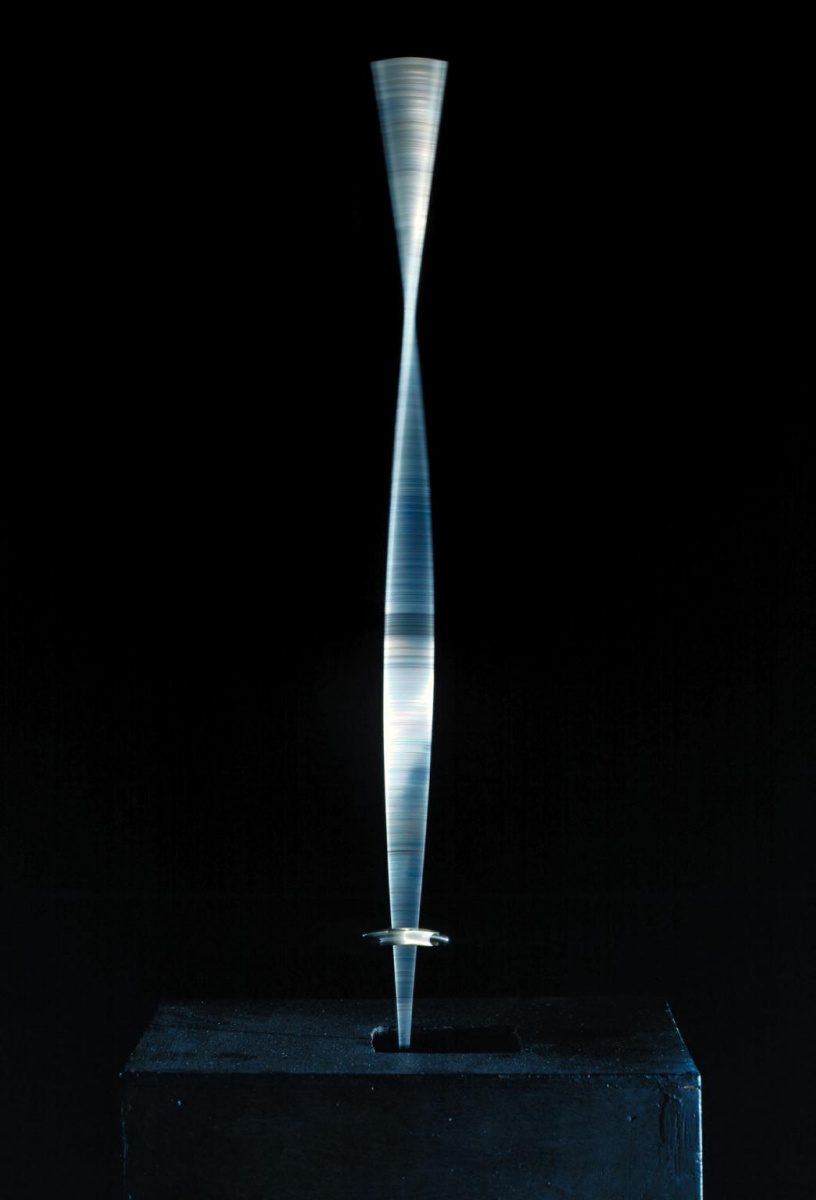

However, it was Naum Gabo who first equipped his sculpture with a motor to make it move. He did not need any technical assistance: due to his engineering education, he had no problems with tasks like that. His Standing Waves is considered the first kinetic work of art. Each time the motor started, the curved plate of metal began rotating and created new mobile shapes.

Bicycle Wheel by Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp, on the contrary, needed no specialised education to make a moving sculpture — he just fixed a bicycle wheel on a stool. By which act, he asserted the idea that any object could be considered a work of art if the viewer saw it in a museum and found any meaning in it. In our selection of classical kinetic artworks, the most unscientific and useless ones are Duchamp’s area of responsibility.

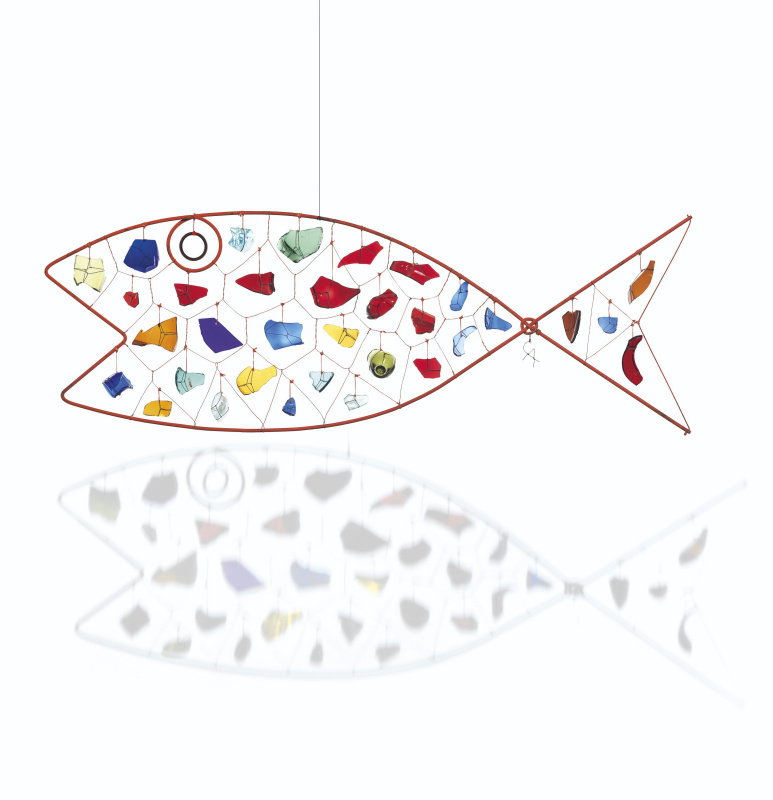

Yes, that is perfectly true: one of Alexander Calder’s mobiles was on display at the exhibition Le Mouvement in the Galerie Denise René. It is curious, though, that he made his first mobile constructions about twenty years before kinetic art became a hot point of discussion. He balanced the elements (balls or plates), suspended them on thin threads or wires, and they moved and turned in the currents of air. That is why Calder is, at the same time, a forerunner of kinetic art and its officially recognised representative.

Kinetic art: A fact sheet

Landmark works

When speaking of kinetic art, people often mention artists whose works contained optical illusions. There was nothing moving, spinning, or squealing: the effect of movement resulted from careful selection of colours and sizes of colour spots. Their combinations made the picture seem vibrating, moving, or even three-dimensional. An example is Victor Vasarely, a painter of optical experiments, and also an art theorist who wrote the Yellow Manifest for the exhibition Le Mouvement. The special terms op art and kinetic art would be invented later, in the sixties. But so far, in Parisian studios, the cosmopolitan company of young mavericks were experimenting with motion, and for them everything came in handy — motors as well as geometrical puzzles.Still, nowadays, kinetic sculptures, in a strict sense, are those that do rotate, produce sounds and light, pump water, or, at the very least, slightly sway. Among such, there are iconic works, the true landmarks of kinetic art.

Jean Tinguely

In 1960, Jean Tinguely assembled a huge machine from parts found on a scrap heap: motors, steel pipes, details of bicycles, empty fuel tanks, troughs, radio-sets, and even a piano. This monster, set ablaze, destroyed itself before the audience of 200 people (among them, by the way, was the abstract Expressionist Mark Rothko — indeed, the clash between kinetic artists and abstract Expressionists seems a sort of exaggeration). By the end of the performance, there was no machine. A few fragments of it are now kept, for example, in the Museum of Modern Art (New York City) and in Tate Modern (London). Tinguely made no secret of the message of the show: it is a hell of a job to make a commercially pointless object that, once made, is destined to return to the scrap heap where it originated.

Jesús Rafael Soto

Works made by kinetic sculptors are generally non-durable — and are not supposed to be so. Being constantly on exhibition, they cannot but wear out. Today’s museum curators and directors have to choose whether to preserve these objects or to follow the ideas the authors put into them. Jesús Rafael Soto designed his penetrables as objects a viewer could literally come inside. The colour cube consisting of long multicoloured threads is a sculpture as well as an activity zone: touching it, listening to the sound of the shimmering threads, walking inside — all this is not only allowed, but necessary.

Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel (GRAV)

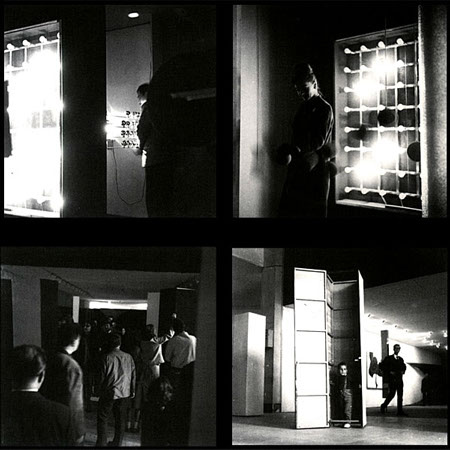

In 1963, when kinetic art was surging in popularity, the company of artists called Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel, or simply GRAV ("Research Art Group"), produced a big labyrinth for the Third Paris Biennial. The structure had twenty locations where viewers could (and sometimes had to) interact with different objects. Light installations, mirrors, mobile bridges, reliefs — everything was part of a large interactive art object created by the eleven artists. "Our labyrinth is just an initial experiment deliberately aimed at the elimination of the difference existing between the spectator and the work. […] We want to get the spectator to participate. We want him to be aware of his participation. […] It is forbidden not to participate. It is forbidden not to touch. It is forbidden not to break," wrote the authors of the most monumental collective artistic project — the GRAV members.

You are an expert if you:

— while hanging a bees-and-mice mobile over your baby’s cot, feel silent gratitude to Alexander Calder for the invention;

— when planning a visit to Paris, mark on your map not only the Louvre, but also the Stravinsky Fountain (next to the Centre Pompidou) designed and built by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint-Phalle;

— despite the strict museum rules, understand that there are pieces of art that not only can, but are supposed to, be touched.

You are incompetent if you:

— are sure that there are no museums where visitors are by any means allowed to touch things, and especially to press any buttons.