Peer-reviewed medical journals are rife with research with diagnoses of deceased artists. The findings are based on both medical records and, in rare cases, analysis of physical remains. But most often luminary doctors turn to the works of the artists for clues.

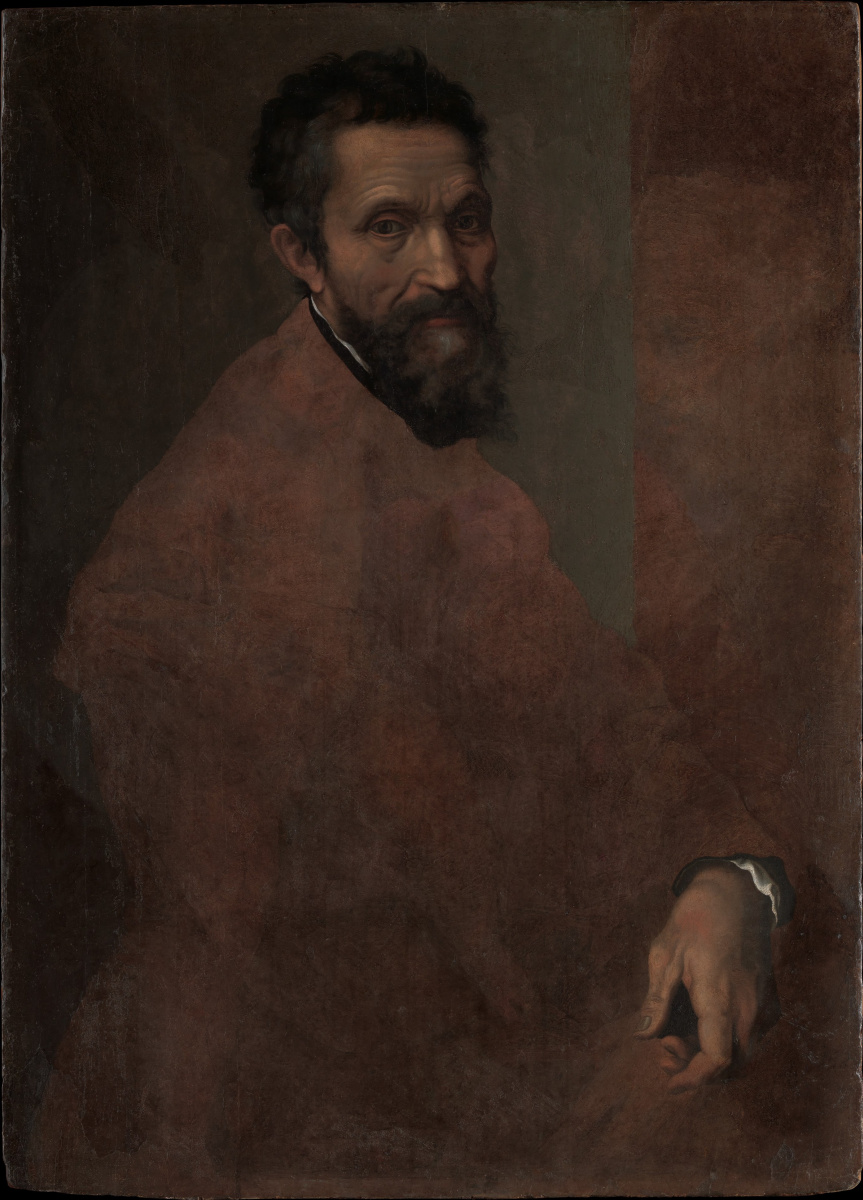

Michelangelo’s sore hands

Once Michelangelo, who was already in his late 80s, wrote to his nephew that his hands, his main instrument, were causing him great pain. "Taking notes gives me great discomfort," complained the Italian Renaissance painter and sculptor. While writing was not easy for him, working with a hammer and chisel on a solid block of Carrara marble was probably simply unbearable. But modern doctors still cannot determine exactly what kind of joint disease the fingers of the famous sculptor suffered from.Squint of Leonardo da Vinci

Artists see the world differently, and some ophthalmologists attribute this creative vision to the peculiarities of their eyes. A 2018 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association claims that Leonardo da Vinci had squint. Such a violation leads to a loss of depth perception — and this ailment could explain the extraordinary abilities of the Renaissance artist. If Leonardo did have a squint, it would be "pretty comfortable for an artist," writes study author Christopher Tyler. He believes that looking at the world with one eye allows you to directly compare nature with a drawn or painted flat image.Distorted vision of El Greco

In 1913, ophthalmologist Germán Beritens argued that the Spanish Renaissance painter El Greco painted such elongated human figures because he had vision problems. He claimed that the artist had severe astigmatism. This is a distortion of vision that occurs due to the fact that light on the retina is focused unevenly. This must have made the artist actually see the figures elongated vertically, which he then transferred to the canvas. Beritens' theory explained El Greco’s uniqueness and caused a sensation when it hit the newspapers.El Greco, Self-Portrait (1600s). Metropolitan Museum, New York

Nearly a century later, another researcher realized that Beritens' logic was intuitive but flawed. In a 2002 study published in Leonardo, University of California psychologist Stuart Anstis argued that if El Greco had astigmatism, vision would distort both his models and their images. In other words, if El Greco painted a portrait of a nobleman, then both the portrait and the sitter had to look alike in his eyes, this would confirm the diagnosis. But Anstis conducted experiments that showed that people with astigmatism can draw proportional objects. El Greco’s elongation was an artistic expression, not a symptom of vision problems, Anstis concluded. The theory he debunked has been termed the El Greco fallacy.

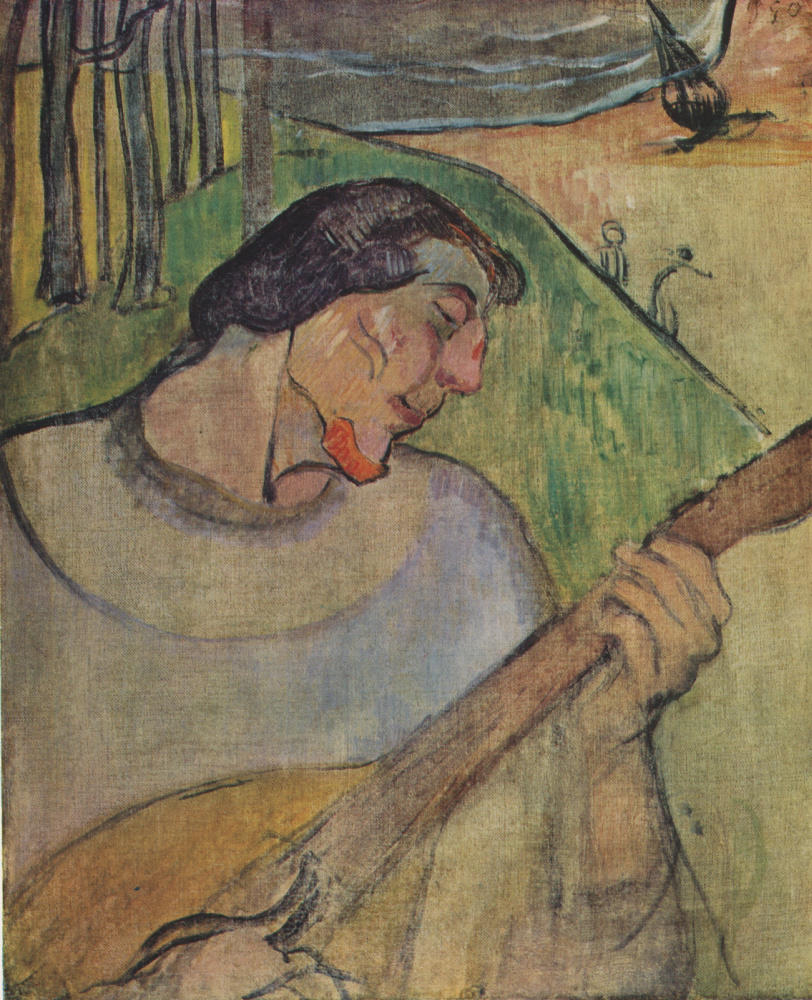

The mysterious death of Paul Gauguin

When the post-impressionist Paul Gauguin died in the Marquesas in 1903, he left four teeth in a glass jar and many speculations about syphilis as the cause of death. The opportunity to answer a number of unanswered questions about his legacy came in 2000. The teeth were extracted from a sealed well near the artist’s hut. Caroline Boyle-Turner, an expert on Gauguin, first wanted to confirm that they really belonged to the French, and then see what can be learned from them.However, this does not necessarily mean that Gauguin was not a syphilitic. This indicates that he did not take such a medicine, or at least not in the dosage that leaves traces.

Claude Monet’s abstract look

The impressionist painter Claude Monet created his expressive works close to abstract already at the end of his career. And a 2015 case study published in the British Journal of General Practice argues that poor eyesight was the cause of innovation. After sixty years, Monet’s age-related bilateral cataract began to progress, which muffled the colours of the surrounding world. In 1913, an ophthalmologist recommended that he undergo cataract surgery. The artist refused, frightened by an unsuccessful operation in front of his colleague Mary Cassatt. He ordered to stick labels on the tubes with paint, so as not to make a mistake in the choice of colour.Metaphysical hallucinations of Giorgio de Chirico

What helped the Italian artist of the 20th century Giorgio de Chirico to create metaphysical images in his mysterious canvases besides boundless imagination? An article published in 2003 in the European Neurology magazine argues that temporal lobe epilepsy may be the answer. It is a neurological condition that in some cases causes complex hallucinations. In his Gebdomeros (1929) book, de Chirico himself wrote that the paintings reflect his hallucinatory experiences. This discovery puzzled doctors, who tried to establish whether the artist’s visions were the result of a migraine headache or temporal lobe epilepsy.Giorgio de Chirico, Metaphysical Self-Portrait (1919). Private collection

The article notes that the consequence of migraine in the subjects was usually blurred or deformed vision, which is not typical for de Chirico’s works. His combination of several realities is more like the complex images that arise during partial seizures. However, the study’s author admits that while the neurological medical histories of artists may provide additional information, "they often lack important clinical data, so the final diagnosis remains controversial".

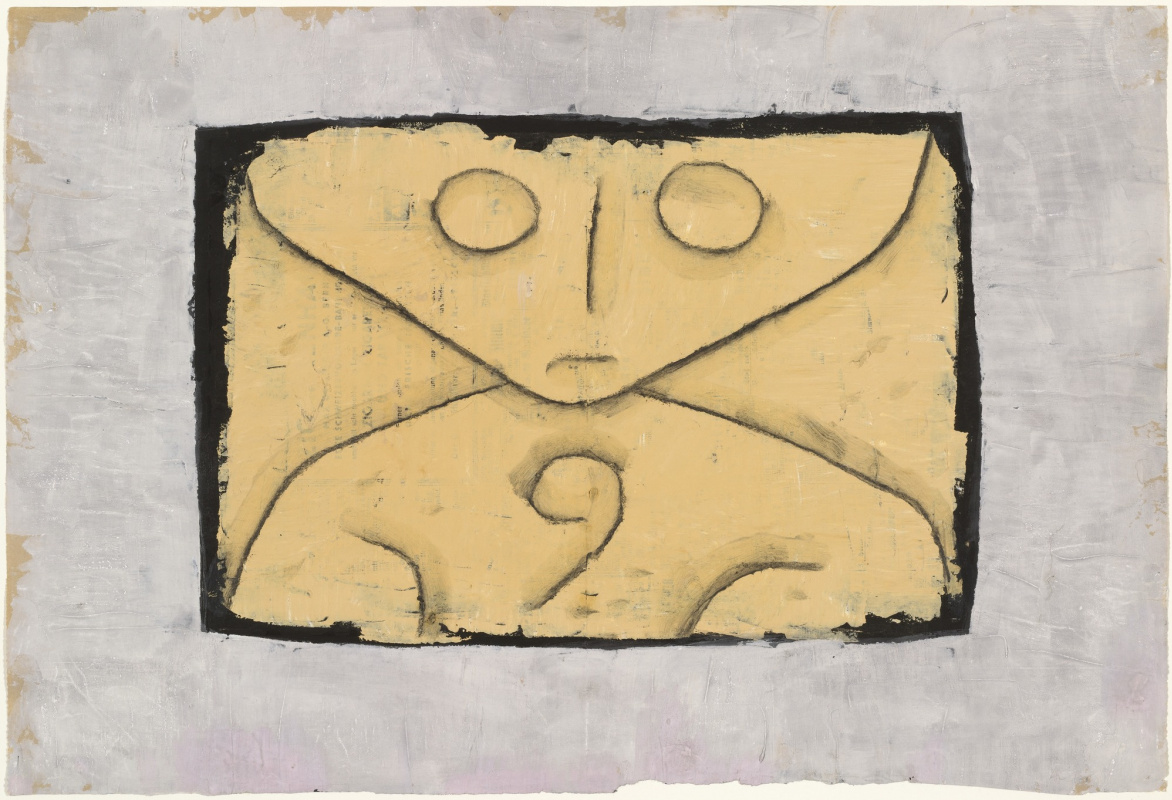

Autoimmune disease of “degenerative” Paul Klee

The last five years of the life of the Swiss and German artist Paul Klee have been fruitful. He created almost 2,500 works of art, a quarter of his entire work. But this work was the most physically exhausting for him. Klee suffered from a combination of skin conditions, ulcers, anaemia, and distension of the oesophagus. During his lifetime, he was not given a final diagnosis, and almost 40 years after his death, these ailments interested a young trainee dermatologist Dr. Hans Suter. For decades, he reconstructed the artist’s medical history, spoke with his widow and only son, and studied unpublished letters describing the symptoms.Based on materials from Artsy