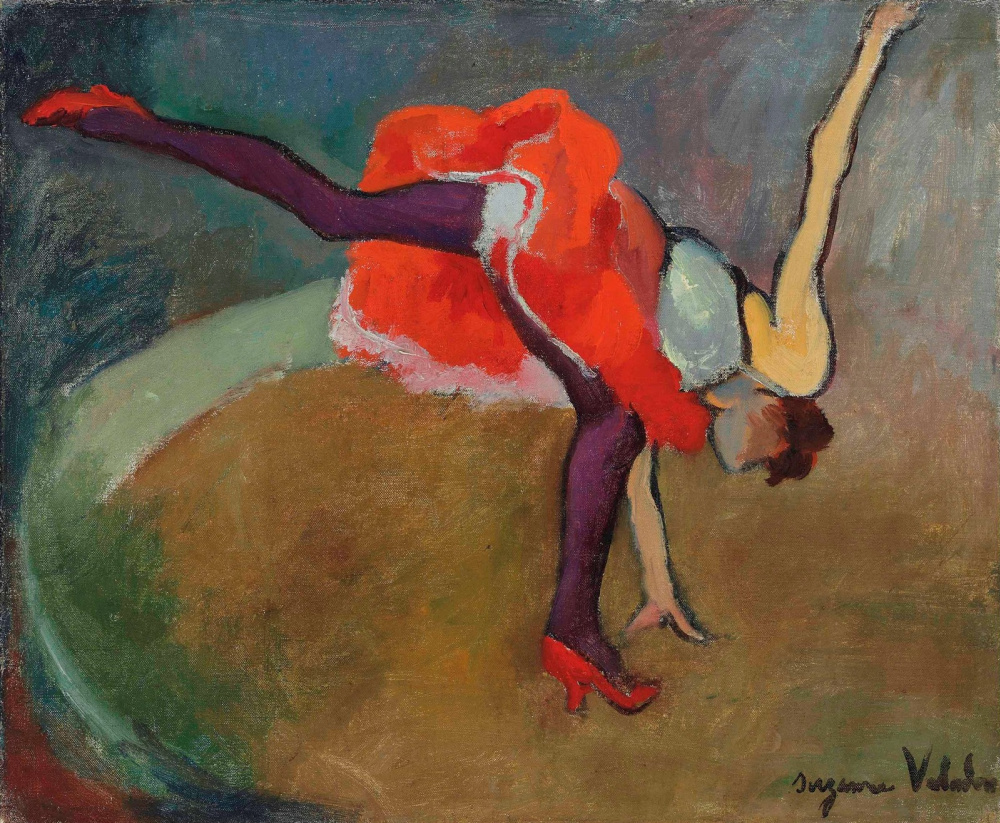

When speaking of Suzanne Valadon, who do we mean? A beautiful, always different model, captured on the masterpieces of the Impressionists? An artist who left her own mark in painting? The mother of a famous artist? A bright, distinctive woman? Or maybe the scandalous lady of Montmartre, a member of the "Cursed Trinity"? Let’s remember all of them. Let’s remember Suzanne Valadon.

Suzanne Valadon was not born Suzanne

Could anyone have imagined that Marie-Clémentine Valadon, the illegitimate daughter of a laundress, would not be famous for her achievements in the field of washing and other cleaning, but would become world famous as a model of the paintings by Renoir, Toulouse-Lautrec, Puy de Chavanne (today we admire her in the most famous museums)? Et cetera.

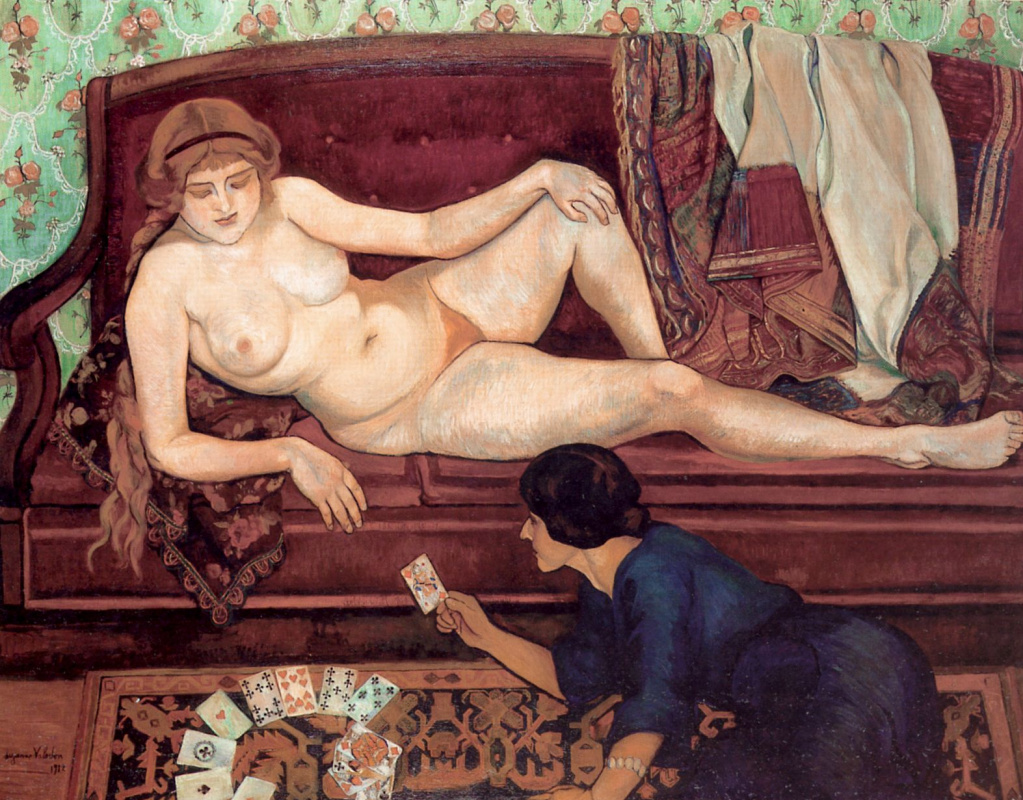

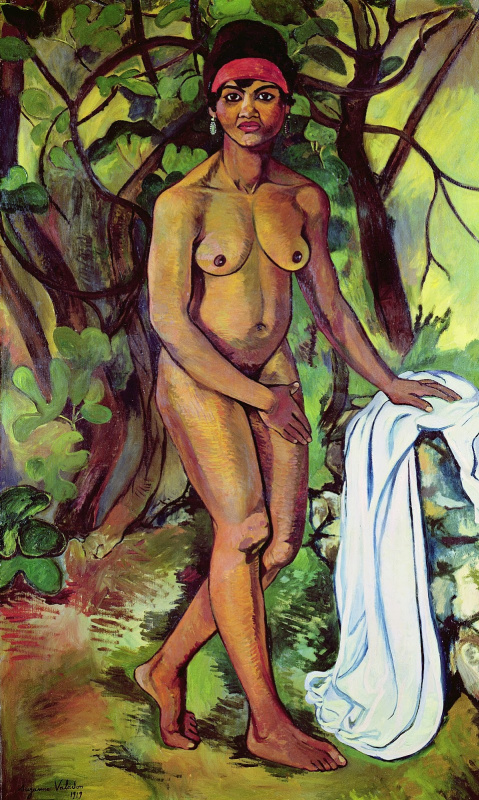

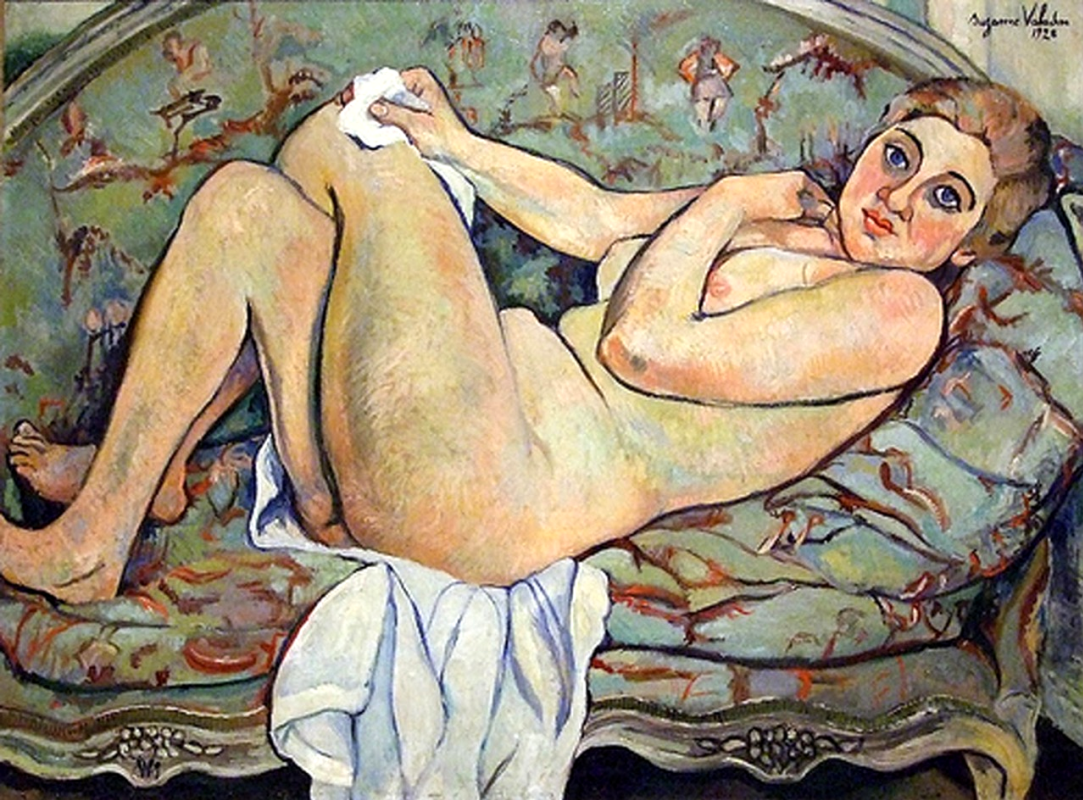

The naked future or fortune-teller

1912, 130×163 cm

We know Suzanne Valadon as an original artist. Posing for these men, Marie-Clémentine learned from them. Artists painted her, she seemed to absorb their skills. The posing sessions were also training sessions for her, which no one suspected for the time being. She is also known as the mother of the artist Maurice Utrillo, whose fame eventually surpassed her own. But why Suzanne? The jealous Toulouse-Lautrec (by the way, he was the first to see her drawings) gave the model this name, who had become famous at that time (in every sense), clearly hinting at the biblical story of Susanna and the elders.

Lautrec introduced famous painters for whom Marie posed as the elders. However, unlike the Biblical Susanna, Suzanne Valadon, who embarrassed the "elders of Montmartre", most often did not refuse them. She did not even know exactly the surname of which eminent artist should have worn her son Maurice Utrillo. The boy was 8 years old when he was adopted by one of Suzanne’s lovers, architect, artist and art critic Miguel Utrillo. On this occasion, he is credited with a joke: "It is a great honour for me to sign the creation of one of the great artists".

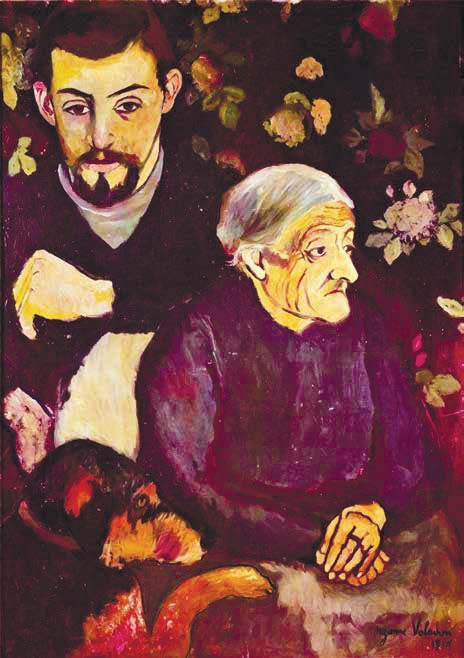

Suzanne Valadon. Miguel Utrillo with a pipe. 1891

Suzanne Valadon: it's not that easy

With Suzanne Valadon, there cannot be any accuracy and certainty: this already becomes obvious when trying to start a standard biography. Name and surname, date of birth — that’s all. We figured out the name above, but the date is also not easy to trace. Marie-Clémentine Valadon was born at 6 a.m. on 23 September 1865 in Madame Guimbaud’s house in Bessines-sur-Gartempe, as it appears in the birth registration book. However, the artist herself insisted on a different date — 23 July 1867. Marie’s mother was a laundress in the Auberge Guimbaud. Her pregnancy caused a lot of gossip: such a quiet, strict and responsible worker, and suddenly such an incident, ah. And what about the daddy, by the way? His name is left unknown. In Suzanne’s stories, he appeared as a man of a famous name and blue bloods, or as just a "simple" banker, and at times as a convict. However, sometimes she stated that her mother found her at the steps of the Limoges Cathedral. Almost all her life, Suzanne Valadon created a myth about herself, as if teasing biographers and descendants with conflicting information and shocking them with unpredictable antics. Take the assertion alone that she fed her unsuccessful paintings to a goat that lived in her workshop. And she attended events with a bunch of carrots as a bouquet!In the last years of her life, Suzanne Valadon, who had already build her fame, abandoned painting. To clearly see and identify the moment when you said everything you could say and stop is, perhaps, even more spectacular than a goat in a workshop. "I had great teachers from whom I took the best of professionalism and skill. I found myself, became who I really am. I had something to say, and I said everything. So what good is it to continue at all costs, to fall into self-repetition, like an old senile? No thanks, not my style."

Not yet feminism, but...

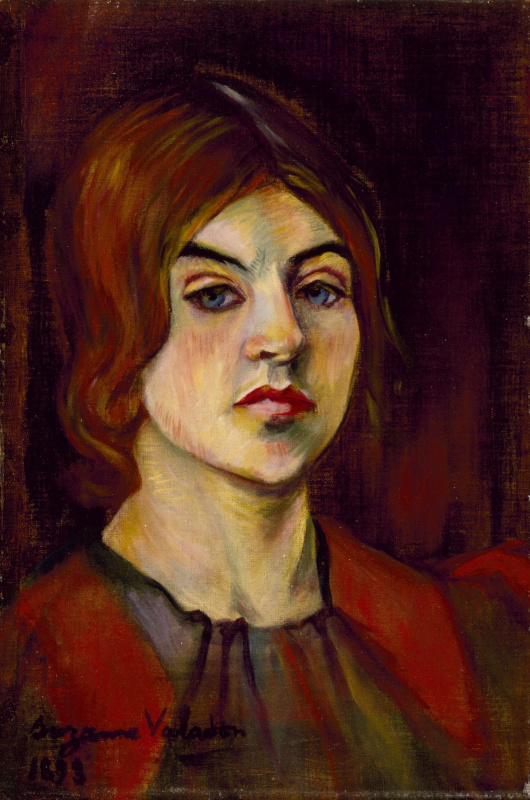

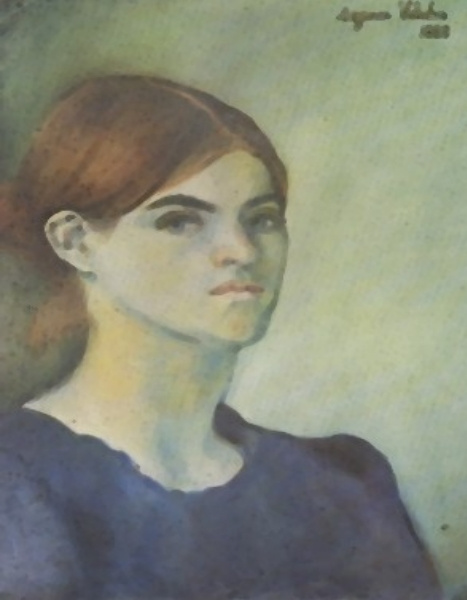

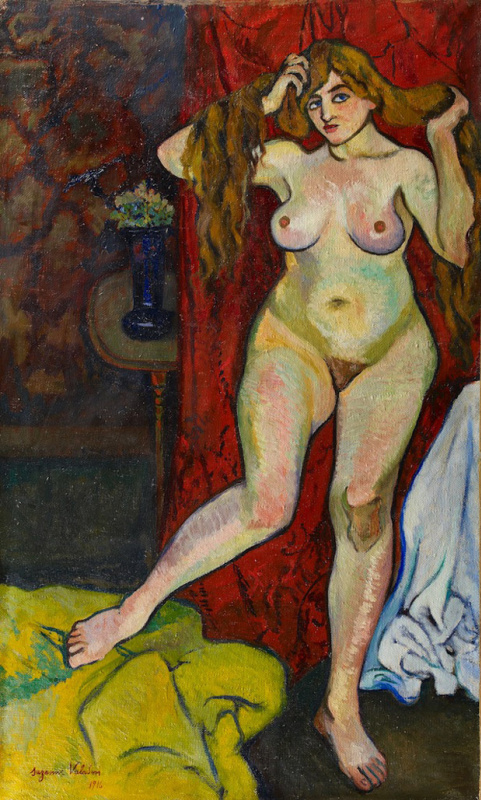

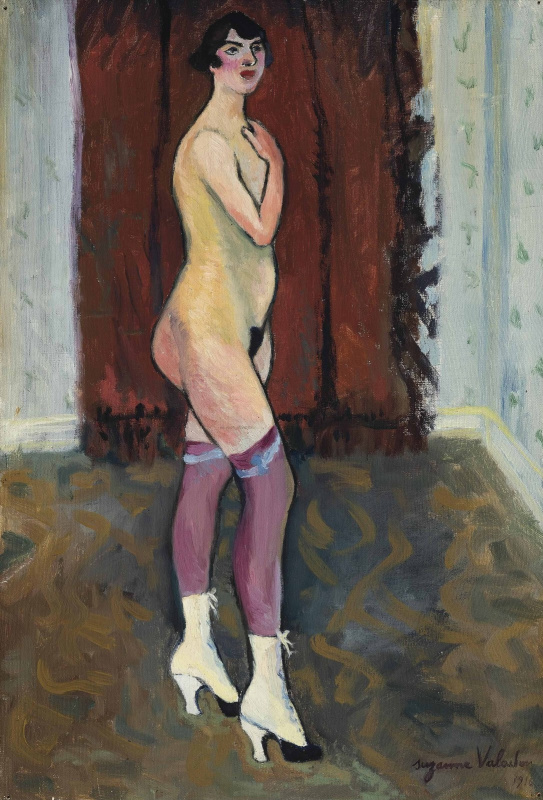

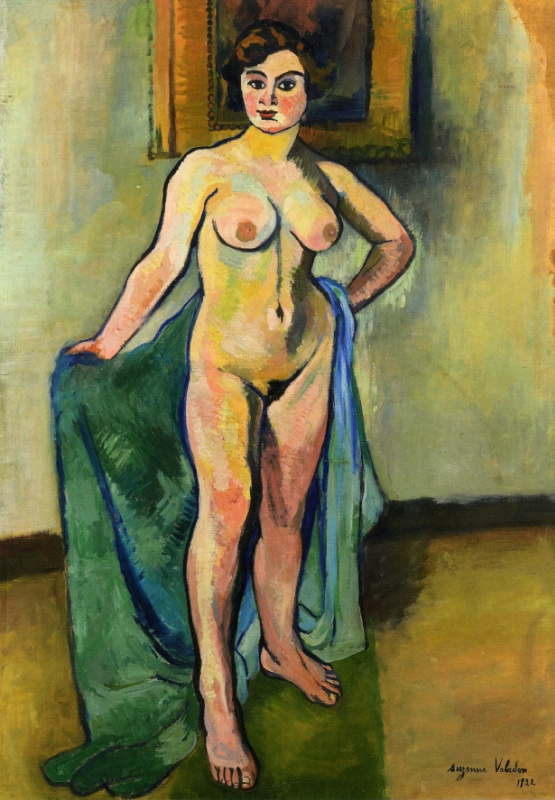

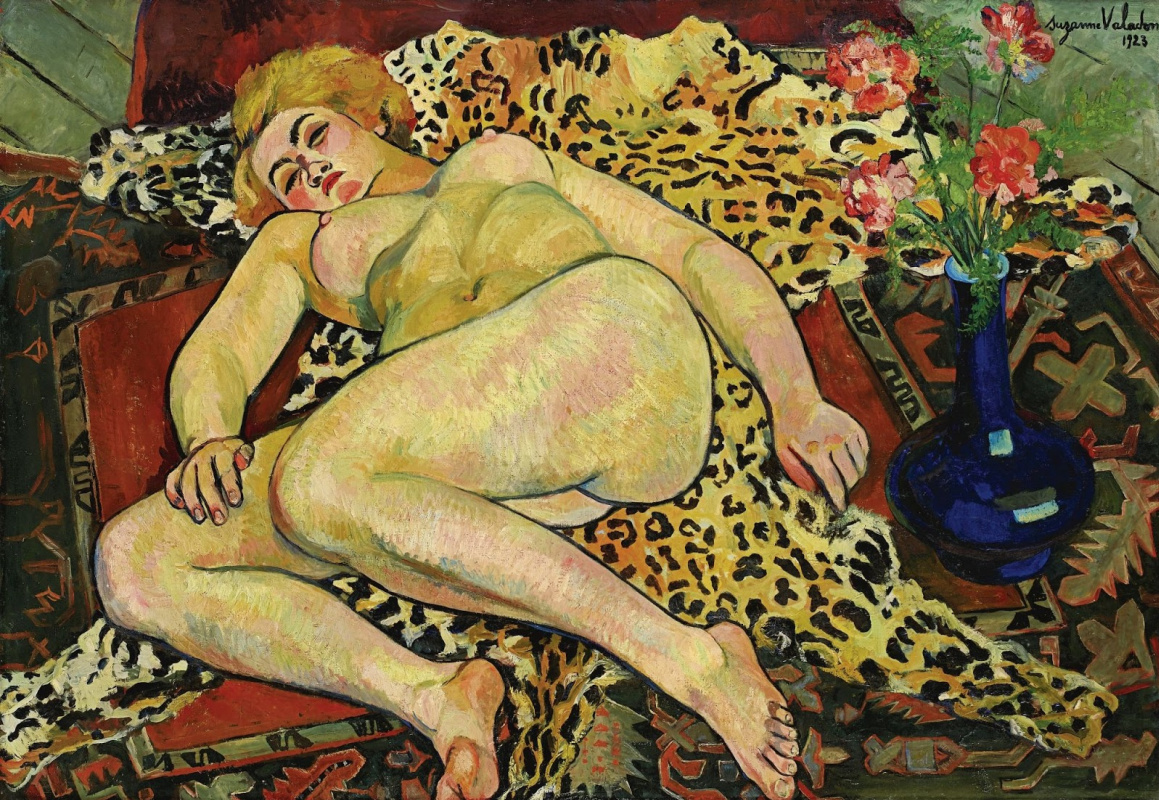

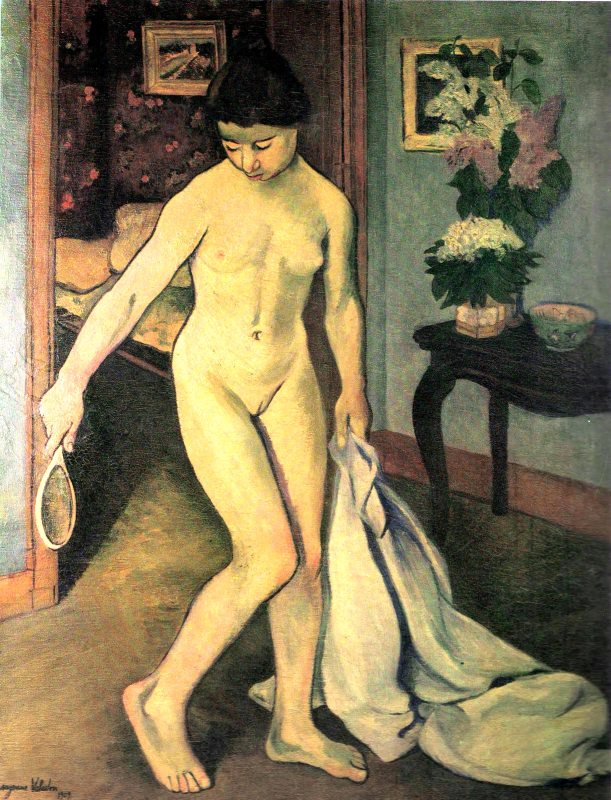

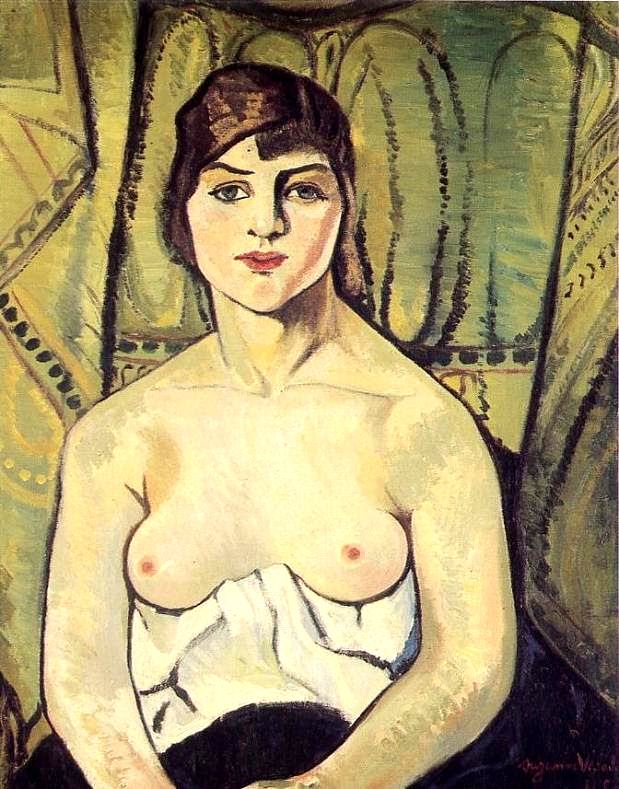

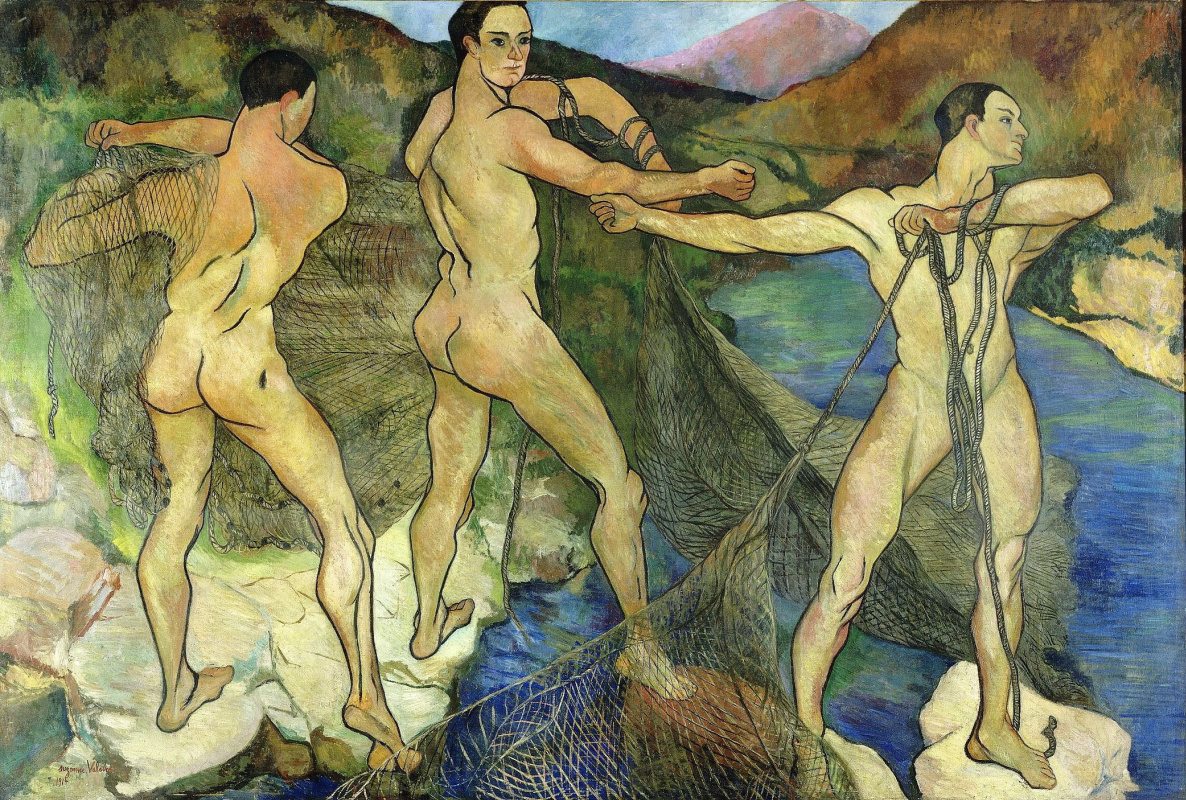

No, she did not call for the struggle for the women’s rights, she did not particularly talk about the role of women and men, about equality. She lived as if everything was already there, and managed to become equal among the best. It was Suzanne Valadon to be the first woman admitted to the Society of Independent Artists (1920). At that time, it was much more difficult for a woman to break through to the art Olympus and firmly win her place than today. Because the position of women in that society left much to be desired, because she worked in the years when brilliant men almost daily created new directions, shocked, impressed, changed the face of world painting forever.She did not care at all whether it was possible for a woman to paint nude at that time (spoiler: no), nudes constitute an essential part of her heritage. We doubt that the word "objectification" was in use then, but her paintings can not be blamed for the fact that women are depicted for the delight of men’s eyes on them. Even the children she painted did not evoke affection, and her naked women were not erotic, and they were sometimes even far from beautiful.

Valadon’s attitude to her models has sometimes been criticized. So, the poet Jean Vertex wrote about her nudes: "She hates women and avenges any charm they have, cursing them with her brush". It was said, perhaps, too sharply, but Valadon surely wasn’t the one who made beauties. She admitted that she did not know how to flatter, did not recommend using her services for women, warning that she would not portray them as charming or embellished, and therefore would certainly disappoint. She was no less strict with herself; one cannot find narcissism in her self-portraits.

Suzanne herself was certainly attractive to men. But was she happy? About her main man we shall talk in the next paragraph, and the artist herself summed up her love affairs at a very respectable age as follows: "Men loved me, it’s true. But I want to be loved by men who have never seen me, I want them to dream of me and imagine me in front of a square of canvas, on which I left a particle of my soul with my paints." It seems that she was more worried about the men who look, looked and would look at her paintings, than those who lusted and adored her.

Big love of Suzanne Valadon

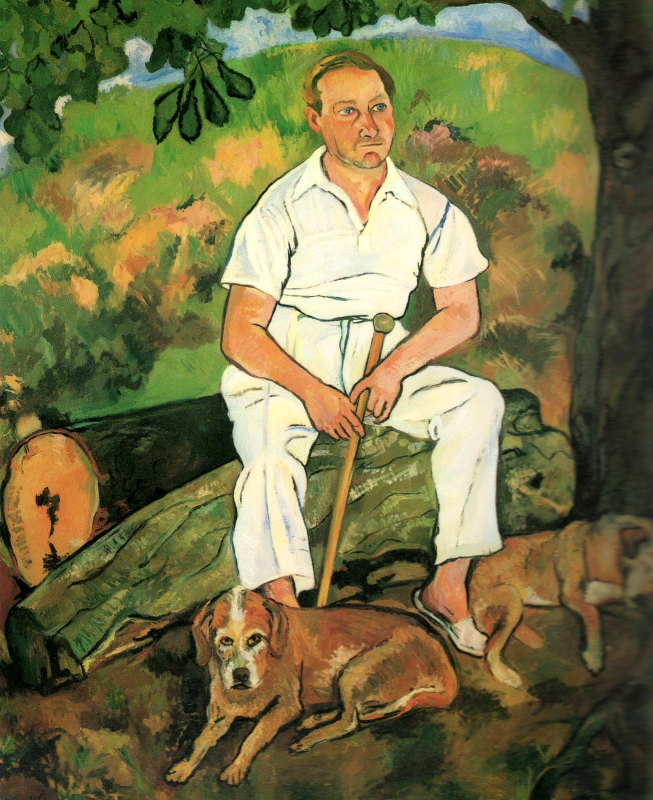

In 1909, the artist fell in love with a friend of her son, 21 years younger than her, André Utter, and invited him to stay with them, and later married him. Utter became the main love of her life, the relationship with him accounts for the pinnacle of her creativity (multiple violent scandals with her son were supplied in the kit). The three of them settled in Montmartre. With Utter, Suzanne Valadon seemed to go full throttle. It hardly was his creative influence — rather, she revealed herself in this love.Valadon began to use oil, moved from drawing to painting, began to exhibit at salons and exhibitions every year, gained her fame, her works began to be actively sold, she was accepted into the Society of Independent Artists. In parallel, the popularity of Maurice Utrillo grew. The Valadon-Utter-Utrillo family was no longer in need. However, you should not think that this story has become a story about a happy family life. In Montmartre, they were nicknamed the "Cursed Trinity": scandals, drunken quarrels, the son’s jealousy of her young husband, the mutual jealousy of the spouses, violent and stormy showdowns that caused a lot of gossip were commonplace. Take alone the situation when Valadon found her young spouse in the arms of some young lady, locked them in the room for a week, and once a day lifted a bucket of boiled cabbage through the window to reinforce her strength, amusing and entertaining the whole block. A harsh way to discourage the urge to play around…

Suzanne Valadon in her workshop. 1926 photo.

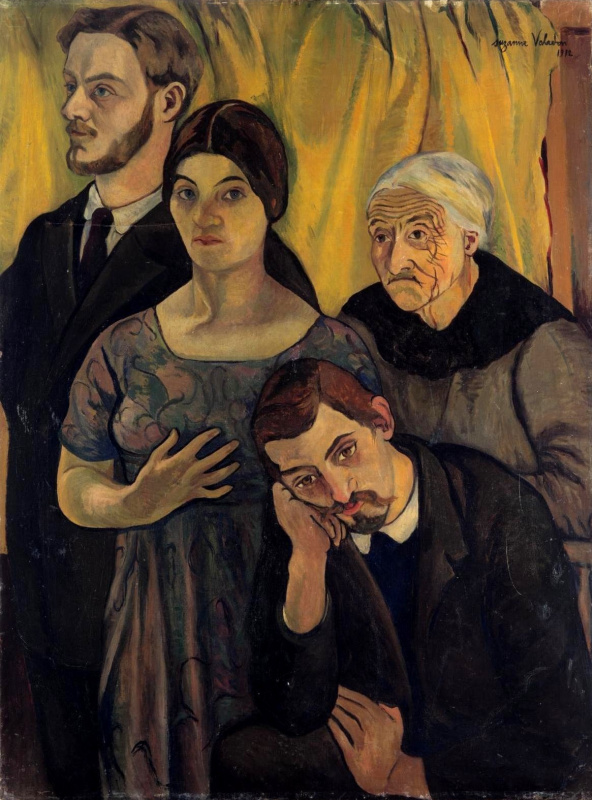

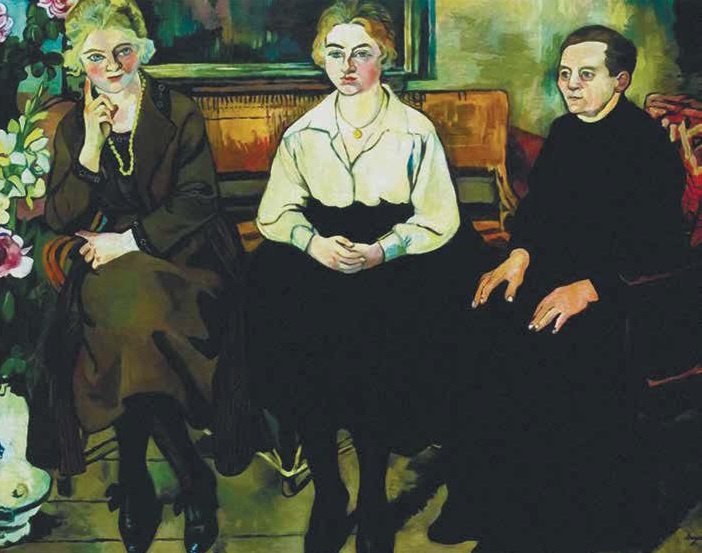

Non-family family portraits

Suzanne Valadon had an uneasy relationship with her mother. Until Madeleine Valadon’s death, they were practically inseparable, but there was always some coldness and distance between them. With her son, it was also very, very difficult. According to some reports, he was addicted to alcohol almost from infancy (grandmother poured wine into his bottle of milk so that the child slept well), Maurice had a painful attachment to his mother all his life.The men loved her, and what about her? She definitely loved André Utter, according to her own statement. But she was completely devoid of illusions about closeness and spiritual community of territorially, kindred and seemingly voluntarily close people. At least, we will come to this conclusion by looking at the family portraits by Suzanne Valadon. All participants are disconnected, separated, looking in different directions and, it seems, at different times. People are as if artificially collected on canvas, they are not together. Obviously, each of them lives his own separate life.

Edgar Degas and Suzanne Valadon

Edgar Degas is a special person in the artist’s work and life. It was he, who was already a recognized master, to give her his blessing by looking at the drawings and summarizing: "You are one of us". He bought several of her works and hung them on the wall in his home. Sometimes Valadon claimed that she did not pose for Degas, but only studied with him, sometimes she repeated the opposite. Their relationship did not go into the personal sphere, although the artist herself did not mind it, but the maître was too "afraid of women".Undoubtedly, the principle of "peeping through the keyhole" proclaimed by Degas is reflected in her numerous nudes, while having a completely different mood. The works are obviously aligned with each other.

And the Portrait of Marie Coca with her daughter Gilberte is a direct reference to Degas, whose style is quite recognizable in the picture hanging on the wall.

Portrait of Maria Coca and her daughter

1913, 16.1×13 cm

Suzanne Valadon’s beautiful life

The 1920s were not only the flowering time of the artist’s work, but also that of the accompanying material wealth. The Bernheim-Jön Gallery signed a contract with her and with Maurice Utrillo, guaranteeing a million francs annually in exchange for future works. Valadon and Utrillo wrote that André Utter was very successful in administrative and production work. The wealthy life began with Suzanne’s lavish antics to make up for previous years of poverty.

Suzanne Valadon, Maurice Utrillo, André Utter in the studio on Avenue Junot. 1926

The people around were shocked; however, they were familiar with such antics. And Suzanne Valadon, who had become very wealthy, wanted to bestow and make happy everyone she could reach. She sent the butcher’s wife, who complained of back pain, to a sanatorium for medical treatment, sent a gift to the postman for his wedding anniversary, fed her cat caviar on weekends, could easily gather fifty poor children on the street and take them all to a circus performance. The streets of Montmartre were her home and her school, and she wanted to thank them for her success. Perhaps. And perhaps the reasons were in something else, as speaking of Suzanne Valadon, one cannot count on unambiguous interpretations.