log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

Astronomer

Jan Vermeer • Painting, 1668, 51×45 cm

Description of the artwork «Astronomer»

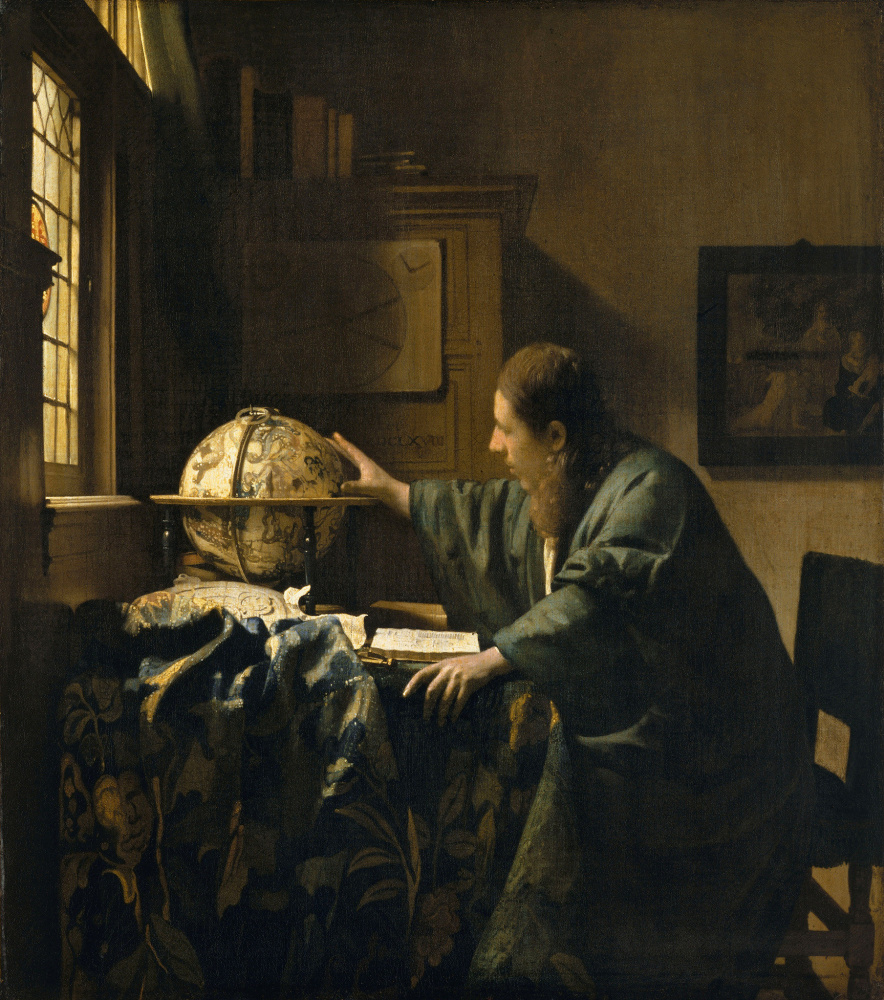

The Astronomer (c. 1668, Musée du Louvre, Paris) by Jan Vermeer portrays a solitary, studious man in his 30s intensely gazing at a celestial globe in a cozy, warmly lit studio, measuring the distance between stars with his thumb and middle finger. He is dressed in a rok kimono, a very symbolic house robe given in limited editions by the Imperial Court of Japan to Dutch merchants living in Japan during their mandatory yearly and highly controlled visits to Edo (now Tokyo). The painting itself is an ode to the 17th century fascination with science and knowledge, which was quickly transforming the world.

The Astronomer and its companion painting, The Geographer, are the only two paintings by Vermeer in which the main subjects are males, and both are men of science. It is likely, in fact, that the same model posed for both works, as they share strikingly similar sharp and intelligent features, and it has been theorized that the model for both was the self-taught scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a likely acquaintance of Vermeer and the founder of microbiology. The rooms also share more than a passing similarity, indicating that they may be one and the same.

Due to the fact that Vermeer seemed to prefer painting interiors with women, often doing chores or playing the piano, he may have been hired to create these two paintings by someone as an illustration of how people of the time envisioned scientists spent their days, looking at celestial globes and contemplating maps, much the way his The Art of Painting (1666, Kunsthistorisches Museum) romanticized the popular image of an artist at work. In this case, van Leeuwenhoek, who lived not far from Vermeer, would have been the perfect model. He is famous to this day for the microscopes he built and for discovering microorganisms, and it is possible that Vermeer, if they were indeed acquainted, would have turned to him to give his painting an air of integrity.

The stark contrast between the light entering through the window — which features a stained-glass decoration missing in The Geographer — and the rest of the room left in shadow forces one to contemplate the scientist as an enlightened truth seeker, and perhaps the sunshine represents the ultimate truth that the astronomer seeks about the real nature of the heavens and man’s place in the Universe.

A mysterious diagram appears above the cupboard behind the astronomer, maybe some astronomical knowledge that has been lost over the hundreds of years since Vermeer painted it. Not so mysterious is the painting-inside-a-painting depicting the Finding of Moses on the wall. Moses was considered a symbol of the ancient wisdom and would have been an inspiration to any 17th century man of science, as well as a metaphorical link connecting the knowledge of the past with the present.

The book Vermeer’s astronomer is consulting is On the Investigation or Observation of the Stars by Adriaen Metius, open to Book III, espousing “inspiration from God” as an important aspect of scientific research.

Next to the globe there lies an astrolabe which has been determined to have been built by Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu, who also authored the map in Vermeer's companion painting The Geographer. These instruments were used for hundreds of years—up until the 18th century — to determine the position of stars and planets in the night sky and for determining latitude and longitude. Such a tool would have been of use for any 17th century astronomer and, in this painting, emphasizes the important role of logic and accuracy in the sciences.

Like many of the world’s greatest works of art, World War II left its mark on The Astronomer — literally, a swastika stamped on the back by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce after it was confiscated from Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild in Paris in 1940 following the Nazi occupation. The Astronomer was one of the first works of stolen art shipped out of France for the Führermuseum Hitler had planned to build in his hometown of Linz, Austria, to turn it into the most beautiful city in Europe and the cultural center of the Third Reich. It was returned to the Rothschilds after the war.

The Astronomer and its companion painting, The Geographer, are the only two paintings by Vermeer in which the main subjects are males, and both are men of science. It is likely, in fact, that the same model posed for both works, as they share strikingly similar sharp and intelligent features, and it has been theorized that the model for both was the self-taught scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, a likely acquaintance of Vermeer and the founder of microbiology. The rooms also share more than a passing similarity, indicating that they may be one and the same.

Due to the fact that Vermeer seemed to prefer painting interiors with women, often doing chores or playing the piano, he may have been hired to create these two paintings by someone as an illustration of how people of the time envisioned scientists spent their days, looking at celestial globes and contemplating maps, much the way his The Art of Painting (1666, Kunsthistorisches Museum) romanticized the popular image of an artist at work. In this case, van Leeuwenhoek, who lived not far from Vermeer, would have been the perfect model. He is famous to this day for the microscopes he built and for discovering microorganisms, and it is possible that Vermeer, if they were indeed acquainted, would have turned to him to give his painting an air of integrity.

The stark contrast between the light entering through the window — which features a stained-glass decoration missing in The Geographer — and the rest of the room left in shadow forces one to contemplate the scientist as an enlightened truth seeker, and perhaps the sunshine represents the ultimate truth that the astronomer seeks about the real nature of the heavens and man’s place in the Universe.

A mysterious diagram appears above the cupboard behind the astronomer, maybe some astronomical knowledge that has been lost over the hundreds of years since Vermeer painted it. Not so mysterious is the painting-inside-a-painting depicting the Finding of Moses on the wall. Moses was considered a symbol of the ancient wisdom and would have been an inspiration to any 17th century man of science, as well as a metaphorical link connecting the knowledge of the past with the present.

The book Vermeer’s astronomer is consulting is On the Investigation or Observation of the Stars by Adriaen Metius, open to Book III, espousing “inspiration from God” as an important aspect of scientific research.

Next to the globe there lies an astrolabe which has been determined to have been built by Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu, who also authored the map in Vermeer's companion painting The Geographer. These instruments were used for hundreds of years—up until the 18th century — to determine the position of stars and planets in the night sky and for determining latitude and longitude. Such a tool would have been of use for any 17th century astronomer and, in this painting, emphasizes the important role of logic and accuracy in the sciences.

Like many of the world’s greatest works of art, World War II left its mark on The Astronomer — literally, a swastika stamped on the back by the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce after it was confiscated from Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild in Paris in 1940 following the Nazi occupation. The Astronomer was one of the first works of stolen art shipped out of France for the Führermuseum Hitler had planned to build in his hometown of Linz, Austria, to turn it into the most beautiful city in Europe and the cultural center of the Third Reich. It was returned to the Rothschilds after the war.