Venice was hated by successive Roman Popes. It did not hesitate to capture areas that had belonged to the Holy See since ancient times: Ravenna, Rimini, Faenza. Padua, Vicenza and Verona paid a tribute to Venice. In April 1509, Pope Julius II imposed an interdict on Venice for its imperialist policy — the prohibition of any church activities on its territory. It turns out, a whole city can be excommunicated.

The second worst enemy of Venice in the days of Titian’s youth was the German ruler Maximilian, who wanted to unite with the Spanish Habsburgs and conquer the Italian lands. The knottiest problem arose when Maximilian intended to meet with the Roman Pope, who promised to crown him as Emperor. There was one snag: to get to Rome, the warlike German had to cross Venice. And Venice legally prohibited him from doing that! Of course, the furious Maximilian then ravaged it with fire and sword, but the very fact of the ban is impressive.

It was in such a city — daring, insolent, and self-confident — that young Titian came from the provincial Pieve di Cadore to stay there forever and win international recognition for himself and Venice.

Titian’s father then decided to let his son go to Venice and learn to draw. But the mother was so distressed that also sent Titian’s brother Francesco with him: it’s not that scary to go together, and it would be more fun. So the brothers Vecellio became the disciples of the mosaicist. The mosaics were popular among the Venetians, but almost nobody painted frescoes. They did not last long in the corrosive, humid air of Venice, containing salty sea suspension — they destroyed during the life of their creators.

Every time after the holidays spent at home in Pieve di Cadore, Titian and Francesco returned to Venice, loaded like pack-mules. With what? The biographer voluptuously lists: "with smoked ham, sausages, spicy sheep cheese, bottles of olive oil and wineskins with good home-made wine…" When it came to food, Donna Lucia Vecellio cared a lot about it. How could it be else, if in Venice, people ate — Mа́mmа Mia!, it’s disgusting even to think about! — sea reptiles and that horrible pasta imported from China by Marco Polo.

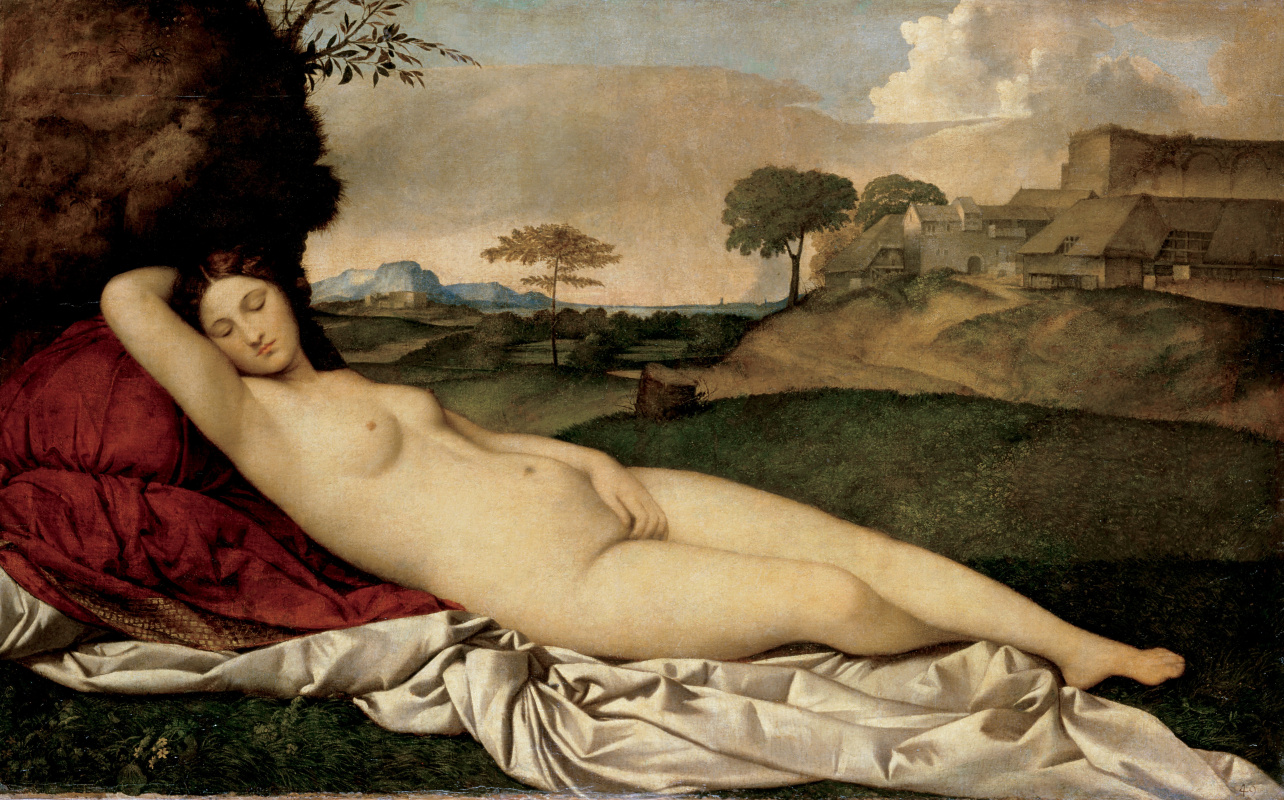

But the plague really played a crucial part in Titian’s life. When Titian was only trying to conquer Venice, there was another name familiar to everybody — Giorgione. Venetians were ready to carry in their arms that frivolous and brilliant artist with an unusually lyrical manner of painting. He was insanely popular among local intellectuals and collectors, but died of the plague quite young. Titian miraculously managed to be near the Giorgione’s house when the fires were already nearby: they burned the plagued things of the deceased in them. At the risk of his life, Titian saved from the fire several of Giorgione’s paintings, including the famous Sleeping Venus. And then the admirers of Giorgione turned to Titian with a request to finish some of the pictures, which their idol didn’t have time to finish. And although Titian did his best and did not claim the authorship of the finished works, later he had to prove for a very long time the authorship of his own paintings: malicious gossip had it that they were created by Giorgione, and Titian tried to grab the credit for his work.

It is interesting that before the withering plague of 1510, the famous Venetian gondolas were bright and colourful. But they had to carry a terrible burden. Thousands upon thousands of corpses sailed along the Grand Canal to the islands of San Lazzaro and Lido, where there were plague cemeteries. Urban legend has it that it was then that the authorities of the Republic of Saint Mark in memory of the deceased decided to leave the gondolas painted with black varnish.

11 thousand prostitutes — a whole social class! They regularly replenished the Venetian treasury with their taxes. In rich Venice, in the 16th century there was a highly developed printing industry and once a year for the convenience of citizens there was published a catalog of prostitutes — with names, addresses and prices, which varied depending on the distance from the center of the city. There were only few restrictions for courtesans: for example, they had to leave the house exclusively in yellow shawls, so that the clients, God forbid, would not confuse them with pious women.

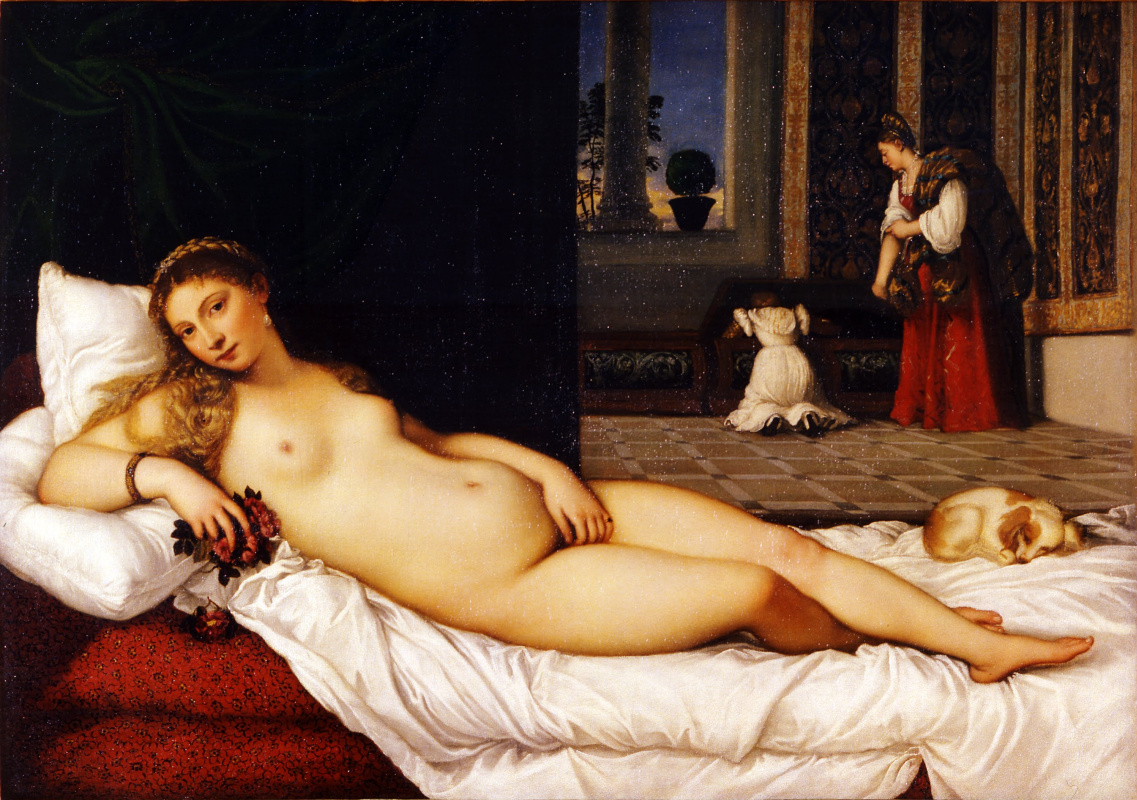

Titian’s personal preferences were not a secret. Being himself strong and well built, he always loved large women. Ve-e-ery large ones, broad-shouldered, bulky — even Rubens was out of his league! Here is how a biographer, resorting to apologetic analogies and equivocation, writes about Titian’s tastes — either artistic, or intimate ones: "The artist did not like the pre-dawn haze, the beginning of the day and the fragility of young maidens. He was more into the beginning of autumn, the hours before sunset, and preferred women with a full-blooded nature who already enjoyed life beauties."

For a long time, following the critic John Ruskin’s example, it was assumed that this picture of Carpaccio depicts two Venetian prostitutes waiting for the client. This, allegedly, was seen from their decolletes and chopines, standing near the balustrade — wedge platform sandals which were often worn by Venetian demi-monde, as well as their expectant glances and poses, and a note, pressed by the dog’s paw. Pavel Muratov, the author of the famous Images of Italy, even believed that on the terrace the courtesans were drying their hair after dying it reddish-gold — the most fashionable colour in Venice. However, after the missing upper part of the board was found in the second half of the 20th century (thanks to it, in particular, it becomes clear that the flower in the flowerpot is a white lily, a symbol of purity), the ladies were "rehabilitated" and are now considered noble Venetians waiting for their husbands to come back from hunting.

For three hundred years Venice managed both to fight and to trade with the Turks. Titian’s teacher Gentile Bellini (Giovanni's older brother, whom Titian was later taught by) lived at the Turkish court, helping his art to build bridges between the warring subjects — the huge Ottoman Empire and the small but proud Republic of St. Mark. According to the modern writer and Nobel prize winner Orhan Pamuk, the profile portrait of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II, the conqueror of Constantinople by Bellini is still considered iconic in Turkey — almost like a portrait of Che Guevara in Cuba.

When Gentile dared to present Mehmed II with a canvas with the severed head of John the Baptist, the sultan noticed that the veins sticking out of his head were painted incorrectly. Gentile tried to object. Mehmed immediately grabbed the sword, cut off the head of the servant standing next to him and began explaining the intricacies of anatomy on a living (or, rather, no longer living) example.

In the heyday of Titian’s talent, the Ottomans were already ruled by another sultan — Suleiman I the Magnificent. Those who watched the Turkish TV series The Magnificent Centuries don’t need any explanation of who he was. In 1521, Suleiman signed peace agreement with the Republic of St. Mark. It is not quite clear whether Titian was at the Sultan’s court, but, for example, his portrait of Laura Dianti (Duke Alfonso I d’Este’s mistress, who took the place of his legal wife, Lucrezia Borgia) was mistakenly considered a portrait of the Sultan’s wife at one time because of the turban on her head. And, unfortunately, until now it is not known for certain who’s depicted in the two portraits below — Suleiman’s wife Hyurrem or his daughter Cameria (Mihrimah), and also whether the portraits belong to Titian, whom they are attributed to, or to the painters from his workshop.

Venice was famous for freedom of speech and antifeudal feuilletons. So it is quite natural that it was there that they began to produce a jaunty printed sheet called "Gazzettino", from which comes the word 'newspaper'. The first media in Venice was named after a small coin with the image of a magpie (in Italian — gazza) — that was the cost of the newspaper.

At the beginning of the XVI century Giovanni Taxis, an entrepreneur from Bergamo, opened a post and transport office in Venice, near the Rialto bridge. Taxis crews could drive even to Verona, or Padua, and very soon he became a monopolist in his field. There is a version that the name "taxi" comes from his name. Whether it’s true or not, Titian enjoyed using the services of the newly invented service, ordering the stagecoaches in the Taxis office. It was especially pleasant that in the cold season some of them had heating systems. The only frustrating thing was that Taxi’s stagecoaches did not want to take people to Titian’s homeland Pieve di Cadore: it was a rugged mountainous terrain, crossed by rivers, and in comparison with Venice, a terrible wilderness.

Titian used all his connections to take this place, although for many years the position of salt mediator was taken by the elderly Giovanni Bellini, his teacher. Titian’s intrigues worked. He got what he wanted and even more — the unfinished palace of Francesco Sforza on the Grand Canal as a place for a workshop. There was everything there: spacious rooms, a glass ceiling, giving the incredible lighting necessary for work, and even a private pier. However, having learned about such inhuman insidiousness, the decrepit Bellini at once changed his mind to die and regained his lost rights through the courts.

Only after his death, Titian, repentant of his blind greed, became a salt mediator.

But why did he ignore Titian in the first one? It turns out that was because of pure jealousy. For Vasari it was important to prove that the birthplace of the great art was Rome and his beloved Florence, but not some sort of the overambitious Venice.

Cover illustration: Titian. Self-portrait. 1550−1562. Berlin Picture Gallery

Author: Anna Vcherashnia