The story of Claude Monet’s life, by any biographer, rarely fails to mention revelations about his vision and medical mysteries. Some have insisted that Monet’s eyes had a special structure and his retinas were unlike those of other people. Others, whether deliberately or by chance, use vivid metaphors of scorched eyes and a sleepy shroud. Still others try to figure out which scientific works on the color spectrum influenced Monet’s work and formed the basis of his view of the world. Paul Cézanne once delightfully said about Monet, probably as a joke: "Monet — only an eye. Yet what an eye!"

Claude Monet in Giverny, 1915

Learn how to see

Claude Monet once shared his dream with American Impressionist Lilla Cabot Perry: "I wish I had been born blind, and then could suddenly see, so I could start painting without knowing what the objects I’m seeing really are." Monet was unlucky; he was born sighted, but all his life he tried to paint as if he was seeing this world for the first time, full of delight, without dwelling on the parts, and without trying to analyze and find meanings.Claude had an innate intolerance of any traditional method of teaching, he wanted to spit on academic drawing lessons and classical composition, and he yawned or became angry when the "knowledge system" was expounded to him. And he ran away each time. When talking about his first real teachers, Eugène Boudin and Johan Jongkind, Monet came right out and said: they developed my vision and taught me to see. No other schools, teachers or theories are needed. There is only vision.

View near Ruel-Le-Havre

1858, 46×55 cm

View at Rouelles Le Havre was the first painting by the 18-year-old Monet, painted outdoors in the company of the lean, stooped sailor Eugène Boudin, who Camille Corot called "the king of the heavens". Monet claimed that on that day he experienced a real revelation that changed his whole life.

Claude Monet at his water lily pond, 1905.

Create feelings

A lot of zeros in auction prices for artworks are mostly about business and smart marketing, but not in the case of Claude Monet. His paintings are completely unscientific and always produce a totally unexpected hypnotic, amusingly sweet and treacherously relaxing feeling.

Villa Bordighera

1884, 115×130 cm

The quests of the Impressionists always revolved around this very idea: to cleanse the world in the painting of meanings and subjects, and fill it with emotions. Modern psychologists uncovering the secrets of Impressionist painting from their ivory tower claim that these artists were technically able to depict the world as a newborn baby sees it — blurred and unclear. And when we look at Haystacks" or "Water Lily Pond", we involuntarily include a psychophysiological memory of a time when we perceived and evaluated what was happening around us very simply: pleasant or unpleasant, safe or dangerous, good- or bad-tasting. Without really knowing what it all means.

"Try to forget what objects you have before you, a tree, a house, a field, or whatever. Merely think, here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives your own naïve impression of the scene before you." This advice from Monet, who was already recognized as a genius, to young artists is much more than just a painting lesson. This lesson on a child’s perception of the world is the only condition for creating an emotional painting. Art experts add that this advice also contains an explicit principle of future abstract art.

Claude Monet and Georges Clemenceau on the Japanese footbridge at Giverny, 1921.

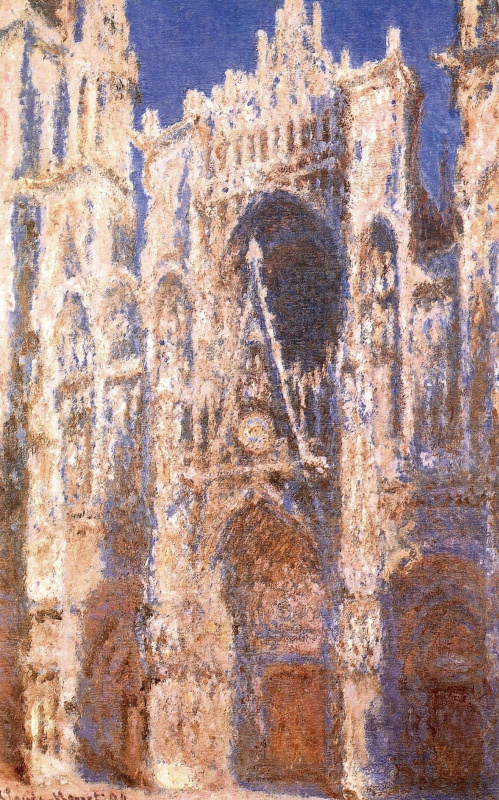

Жить глазами

Georges Clemenceau, a renowned and eloquent politician beloved by the French, and the "father of victory", was Monet’s closest friend in the last few decades of his life, a close neighbor and the inspiration for the famous water lily murals that are now in an oval hall of the Orangerie Museum. And by a rare, happy coincidence, he was also a great connoisseur of art. However, before all these celebrated activities, Clemenceau was a doctor. Thus, his persistent talk about Monet’s "unique retinas" should be taken more as a scientific term and an attempt to study it, rather than a figure of speech. Here is an example: "Claude Monet’s garden can be considered one of his artworks, in which the artist miraculously embodied the idea of transforming nature by the laws of light painting. His studio was not limited by walls; it went outside, where color palettes were scattered everywhere, training the eyes and satisfying the retina’s insatiable appetite for perceiving even the slightest flicker of life.""If you look closely at Monet’s cathedrals, it seems like they are painted with some kind of iridescent mortar thrown onto the canvas in a outburst of rage. But in its wild outburst, there is as much passion as there is exact knowledge. How was the artist, who was only a few centimeters away from his canvas, able to capture this subtle yet precise effect that could be seen only at a distance? Apparently, thanks to the mysterious quality of his retinas. But only one thing is important to me — that I’m seeing this whole pile in its entirety, in its majestic grandeur and power," wrote Clemenceau about the famous series depicting Rouen Cathedral.

Here, it is very tempting to ascribe the Monet’s genius to a physiological gift, but the most interesting part comes later. The artist created his last masterpieces when he was nearly blind, and his retinas had stopped functioning.

Claude Monet on the main path of his garden at Giverny.

Learn how not to see

Sunlight, sultry summer and icy winter, and every single day burned Claude Monet’s eyes, bringing the inevitable closer. He was healthy and strong, hardy and energetic for his 60-plus years. But his eyesight was deteriorating year by year. The lenses became dull and cloudy, and the retinas so incredibly constructed by nature received less light, colors looked dull and gloomy, and the whole outside world seemed to be covered with a yellowish filter.

The websites of modern ophthalmology clinics have pictures simulating how the world looks with cataracts (photo above).

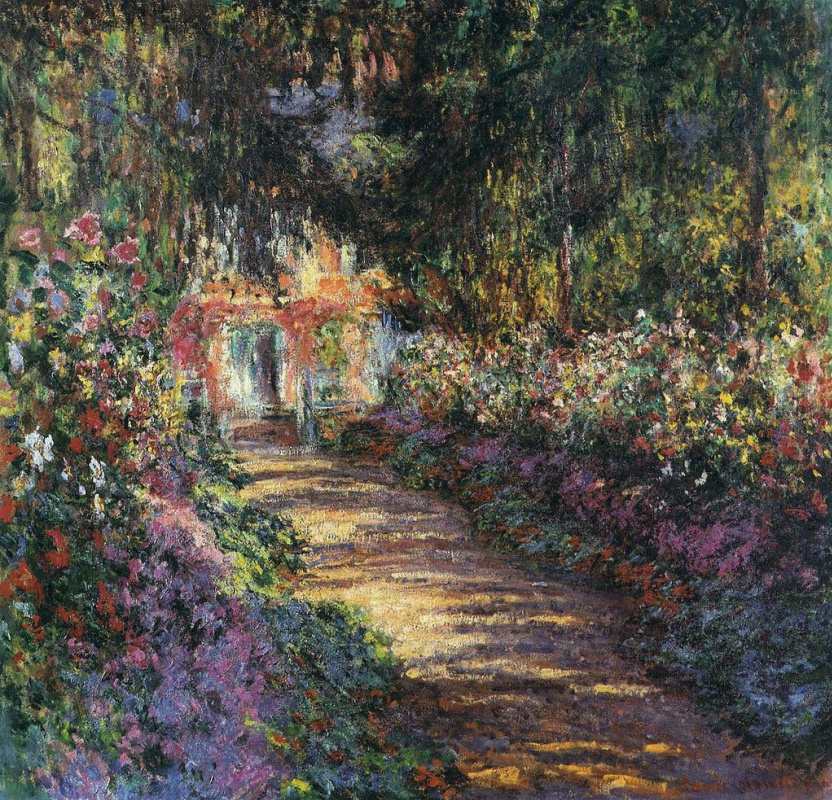

Arthive has processed the photos from Monet’s garden at Giverny to show how Claude Monet might have seen his flowers when he was suffering from cataracts, and has compared them with the artist’s later artworks. (See the original photos with views of the garden at Giverny at dturista.com).

Arthive has processed the photos from Monet’s garden at Giverny to show how Claude Monet might have seen his flowers when he was suffering from cataracts, and has compared them with the artist’s later artworks. (See the original photos with views of the garden at Giverny at dturista.com).

The path through the garden at Giverny

1902, 89×92 cm

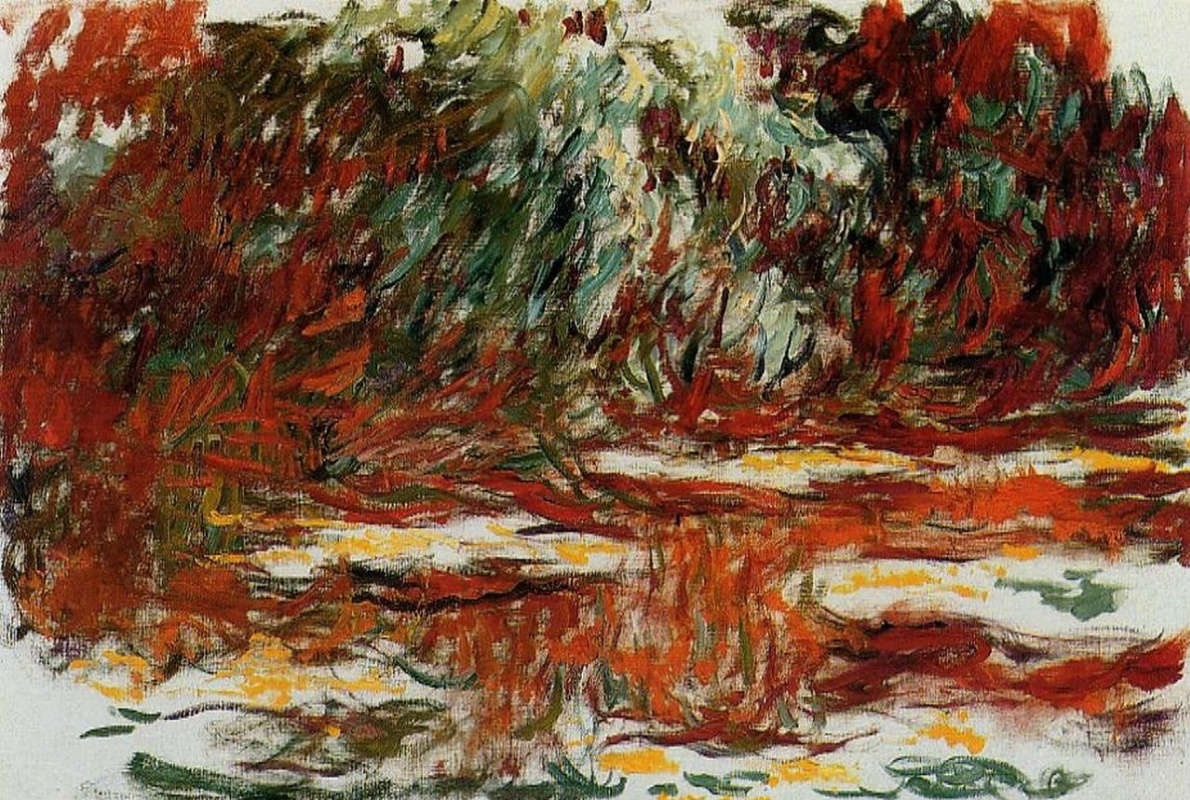

Pond with water lilies (Japanese bridge)

1900, 90.2×92.7 cm

Monet never signed his favorite paintings in order to avoid the temptation to sell them. Only his closest friends could attempt to buy one of them, and only on really lucky days. It took actor and director Sacha Guitry several months to persuade Claude to sell him one of these artworks from old stocks. Monet sighed, signed the canvas and whispered: "Listen, Sacha. I signed it ‘81, but I actually painted it in ‘82. I don’t want to deceive you. It’s just that it’s easier for me to write 1 instead of 2…"

He was 72 when the doctors made their diagnosis: cataracts in both eyes, vision in the left eye was one-tenth of normal, and the right eye could only distinguish light.

The doctors also explained how colors were perceived if a cataract was present: the lens performs an important protective function by absorbing light waves before they reach the retina. Over time, the lens becomes cloudy, turns yellow and starts absorbing all shorter light waves, thus distorting color flows falling on the retina. This means that the retina no longer receives reliable information about the surrounding world due to the cloudy lens.

He was 72 when the doctors made their diagnosis: cataracts in both eyes, vision in the left eye was one-tenth of normal, and the right eye could only distinguish light.

The doctors also explained how colors were perceived if a cataract was present: the lens performs an important protective function by absorbing light waves before they reach the retina. Over time, the lens becomes cloudy, turns yellow and starts absorbing all shorter light waves, thus distorting color flows falling on the retina. This means that the retina no longer receives reliable information about the surrounding world due to the cloudy lens.

Doctor Coutela almost certainly knew what he had to do, meaning he was a daring and very brave man with enormous self possession: he offered to perform an eye operation. An operation on Monet’s eyes! Claude was first indignant, then he cried aloud, then was silent for days at a time, and then complained to his friend George Clemenceau that he was afraid to even think about the clinic and the doctor: "How do I know they won’t give me someone else’s eyes? I need Monet’s eyes! How else will I continue to work?"

In the photo: Claude Monet, August 27, 1905.

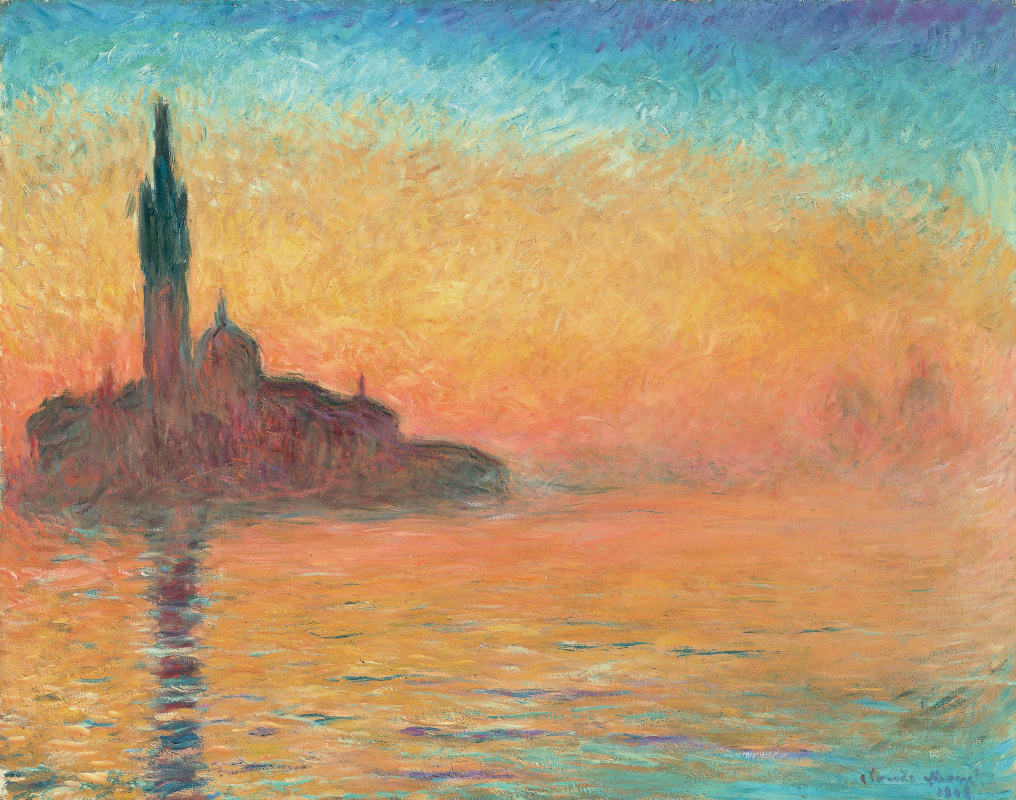

Doctors could already see the special color perception of a person with cataracts in Monet’s Venice cycle. But as 1923 approached, when the artist decided to have the operation, the more obvious and unmistakable these changes became.

Claude Monet was not exactly an easy, grateful patient. He arrived at Doctor Coutela’s Paris clinic exhausted and in abject despair; and when he saw the scalpel approaching his eyes, he panicked and was seized with nausea and vomiting. Afterwards, the patient was strictly ordered not to move for three days after the operation. On the first night, Monet tried to tear off the bandage, and in a fit of rage, he shouted that he would rather be completely blind than lie motionless for three days.

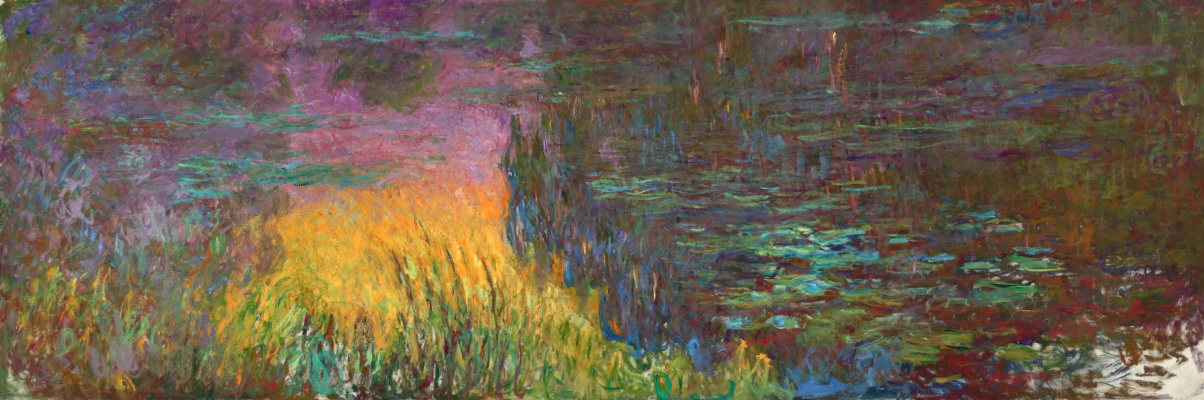

Doctor Coutela performed a total of three of these operations on Monet’s right eye. However, they did not have the expected result, and the world swam before his eyes once again. Now the eye from which the lens had been surgically removed became sensitive to short wavelengths and saw everything in a deep blue-violet color. At the same time, his left eye continued seeing everything in yellow. His brain was unable to combine the two images and showed a split picture. "It would be better to be blind than see nature as I see it," Monet said in despair. And he returned to work on his last masterpieces.

Doctor Coutela performed a total of three of these operations on Monet’s right eye. However, they did not have the expected result, and the world swam before his eyes once again. Now the eye from which the lens had been surgically removed became sensitive to short wavelengths and saw everything in a deep blue-violet color. At the same time, his left eye continued seeing everything in yellow. His brain was unable to combine the two images and showed a split picture. "It would be better to be blind than see nature as I see it," Monet said in despair. And he returned to work on his last masterpieces.

Smoke Break. Claude Monet painting water lily murals for the Orangerie Museum, 1926.

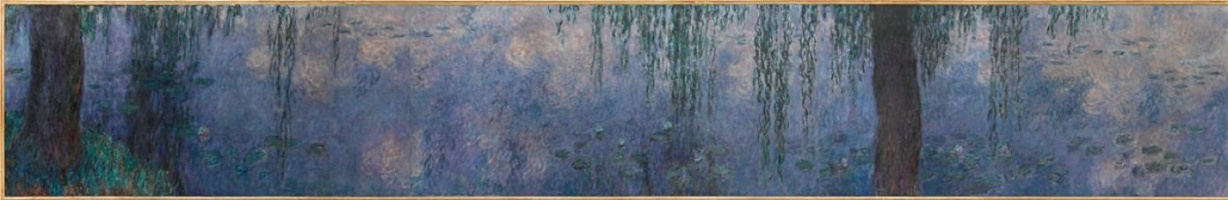

Instead of vision

"Cataracts forced him to trust his imagination rather than his vision," writes the British art critic Waldemar Januszczak. The 86-year-old artist painted the 8 huge murals in the oval halls of the Orangerie Museum, which create a sense of a translucent, lulling, resonant and enveloping watery infinity, without a lens in his right eye, and a cataract in his left.

Water lilies

1926

Nenufar

1926, 602×219 cm

Surrealist artist André Masson called the installation at the Orangerie the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism.

Title illustration: Claude Monet, "Poplars near Argenteuil", 1875 and Auguste Renoir, "Portrait of Claude Monet", 1875

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Photo reproduction: Tatiana Somova

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Photo reproduction: Tatiana Somova