Shishkin became a classic during his lifetime. But the textbook fame sometimes does not allow the viewer to really meet the artist. Consciousness helpfully shows some soulless idol whom everyone knows, everyone saw, but did not try to peer. We would like to remove this gilding from the image of Ivan Shishkin, who was a loving, impetuous, sometimes awkward and touching person.

Shishkin is often reproached for the excessive naturalism of his paintings, they are said to be some kind of photograph, and not art. Ivan Ivanovich really considered loyalty to nature the most important property of the landscape

. However, everything is not so unambiguous with the interpretation of his paintings, there were also funny stories. Once Shishkin worked on location, finished a sketch of a pine forest, put the finishing touches and was very pleased with the result: the sketch

reproduced the landscape

with protocol accuracy. The treetops streaming skyward, the shaky thick air of the forest thicket, the dense, scaly bark of the trunks. It seems, if you look closely, you can identify each needle.

A local peasant woman approached Shishkin, looked at the creation of his hands for a long time, while sighing heavily. Artist asked her if she liked the picture, and the woman nodded fervently, saying he couldn’t do better, she liked it! "What is depicted here?" Shishkin asked. He received an instant answer: "It must be the Holy Sepulcher". Seeing the expression on the face of the strange nobleman, the peasant woman understood that she mistook, thus she hastened to console him: "Didn't I guess? Well, wait a minute, I’ll call for my son Vasyutka, he is literate, he will quickly guess."

A local peasant woman approached Shishkin, looked at the creation of his hands for a long time, while sighing heavily. Artist asked her if she liked the picture, and the woman nodded fervently, saying he couldn’t do better, she liked it! "What is depicted here?" Shishkin asked. He received an instant answer: "It must be the Holy Sepulcher". Seeing the expression on the face of the strange nobleman, the peasant woman understood that she mistook, thus she hastened to console him: "Didn't I guess? Well, wait a minute, I’ll call for my son Vasyutka, he is literate, he will quickly guess."

In front of the mirror. Reading the letter

1870, 58×39 cm

Love for nature was not the only strong feeling in Shishkin’s life. It is known about the artist’s two wives, both of them died early, leaving deep wounds in his soul. In both cases, his native Yelabuga helped him to return to life. And there was also a love story associated with Yelabuga. During one of his last visits to his small homeland, Shishkin conceived a passion from a local young woman. The passion was mutual, the woman bore him a child, but neither the official marriage nor the recognition of the child followed. In the artist’s biography, written for the ZhZL series, Lev Anisov mentioned this fact, but the trace of that woman, as well as the child, was lost.

Deadwood. Belovezhskaya Pushcha

1892, 28.4×43.4 cm

Shishkin disliked official events, long speeches and all kinds of meetings very much. He was disgusted with the very thought of putting on a tailcoat, listening and making speeches, making courteous bows… However, sometimes this could not be avoided. At the 20th traveling exhibition, Ivan Shishkin personally met with Emperor Alexander III. At that time the artist exhibited his Summer Day and one of his numerous images of a pine forest. The Emperor unambiguously expressed his desire to contemplate the famous painter of forest landscapes. So Shishkin had to rent the hated tailcoat. In the memoirs of Yakov Minchenkov, we read about this meeting:

"So you are the landscape painter Shishkin?" the tsar asked.

He shook his beard, silently agreeing that he was indeed the landscape painter Shishkin. The tsar praised him for his work and wished that Ivan Ivanovich go to Belovezhskaya Pushcha and paint a real forest there, which he cannot see here. Shishkin also had to shake his beard as a sign of consent.

The Tsar was seen off, Ivan Ivanovich approached a mirror, looked at his figure, spat, threw off his tailcoat and left home without it, wearing a fur coat.

The trip took place, but Shishkin did not experience the solitude and so much appreciated merging with nature that time. A carriage was sent from the royal hunting palace, the artist was coddled like a little child, which irritated him excessively. He could not take a step, so as not to stumble upon the ingratiating "wherever you want" and "what you please". Once Shishkin deepened into a forest thicket, hoping to take a break from the intrusive courting at least and to work to his heart’s content. Instead of the courtiers, the forest manager came, looked at the sketch , in the foreground was a half-dried tree. He crumpled and asked to erase this tree. Shishkin was surprised, and the manager explained: "After all, you will take the picture to St. Petersburg, and they will look there and say: ‘Well, the manager is quite nice — he brought the forest to the dry trees!'"

"So you are the landscape painter Shishkin?" the tsar asked.

He shook his beard, silently agreeing that he was indeed the landscape painter Shishkin. The tsar praised him for his work and wished that Ivan Ivanovich go to Belovezhskaya Pushcha and paint a real forest there, which he cannot see here. Shishkin also had to shake his beard as a sign of consent.

The Tsar was seen off, Ivan Ivanovich approached a mirror, looked at his figure, spat, threw off his tailcoat and left home without it, wearing a fur coat.

The trip took place, but Shishkin did not experience the solitude and so much appreciated merging with nature that time. A carriage was sent from the royal hunting palace, the artist was coddled like a little child, which irritated him excessively. He could not take a step, so as not to stumble upon the ingratiating "wherever you want" and "what you please". Once Shishkin deepened into a forest thicket, hoping to take a break from the intrusive courting at least and to work to his heart’s content. Instead of the courtiers, the forest manager came, looked at the sketch , in the foreground was a half-dried tree. He crumpled and asked to erase this tree. Shishkin was surprised, and the manager explained: "After all, you will take the picture to St. Petersburg, and they will look there and say: ‘Well, the manager is quite nice — he brought the forest to the dry trees!'"

In the photo from the Hermitage collection: the billiard room of Nicholas II. The large landscape

in the centre is the Pine Forest by Shishkin. Now this painting is in the collection of the Far Eastern Art Museum in Khabarovsk.

Emperor Nicholas II was an admirer of Shishkin’s work, but he did not always manage to get what he wanted in his collection. The attitude towards those in power as thought they were "dearer than one’s own father" was not usual for Shishkin. For example, his nephew Nikolai Stakheev was definitely nicer to him than the tsar.

The public first saw the At the Edge of a Pine Forest painting in 1897 at the 25th Exhibition of the Itinerants. The picture was shown in St. Petersburg and Moscow. The Emperor liked it extremely, he wanted to purchase it for his personal collection, but was refused. Whereas the desire of his nephew Nikolai Stakheev, the owner of a rich collection of paintings, to buy this painting, Shishkin answered with joyful consent. Therefore Nicholas II was hoodwinked, and the relative of the artist had the picture. By the way, its further fate is also interesting.

The public first saw the At the Edge of a Pine Forest painting in 1897 at the 25th Exhibition of the Itinerants. The picture was shown in St. Petersburg and Moscow. The Emperor liked it extremely, he wanted to purchase it for his personal collection, but was refused. Whereas the desire of his nephew Nikolai Stakheev, the owner of a rich collection of paintings, to buy this painting, Shishkin answered with joyful consent. Therefore Nicholas II was hoodwinked, and the relative of the artist had the picture. By the way, its further fate is also interesting.

On the edge of a pine forest

1897, 109×162 cm

After the 1917 revolution, Stakheev and his family emigrated to Paris. The Moscow House and most of its rich collection were nationalized. However, some objects of art that were especially dear for Shishkin’s nephew were shipped out of the country, including the At the Edge of a Pine Forest painting. In the 1920s, the painting was bought from the Stakheevs by the Belgian artist Charles Defreyn. It was his descendants who exhibited the work at the Sotheby’s auction in June 2016. The Shishkin’s painting turned out to be the most expensive lot at the auction of Russian art, its estimate was determined at 500 to 700 thousand pounds (that is, the upper limit was one million dollars) and was exceeded twice. Surely, the absolutely transparent provenance also had an impact on pricing. A serious struggle broke out, four buyers held out the longest. As a result, on 7 June 2016, the work was sold for 1,385,000 pounds (2,009 thousand dollars). The buyer was in the hall, but did not want to divulge his name.

The At the Edge of a Pine Forest painting depicts the expanses of his native Yelabuga, so much dear to the artist’s heart. Some researchers believe that Shishkin portrayed himself as the figure on the cart. Not long before that, he buried his wife and two sons, and all he had was his native Yelabuga. The picture echoed his most famous canvases — Rye and Noon. In the vicinity of Moscow.

The At the Edge of a Pine Forest painting depicts the expanses of his native Yelabuga, so much dear to the artist’s heart. Some researchers believe that Shishkin portrayed himself as the figure on the cart. Not long before that, he buried his wife and two sons, and all he had was his native Yelabuga. The picture echoed his most famous canvases — Rye and Noon. In the vicinity of Moscow.

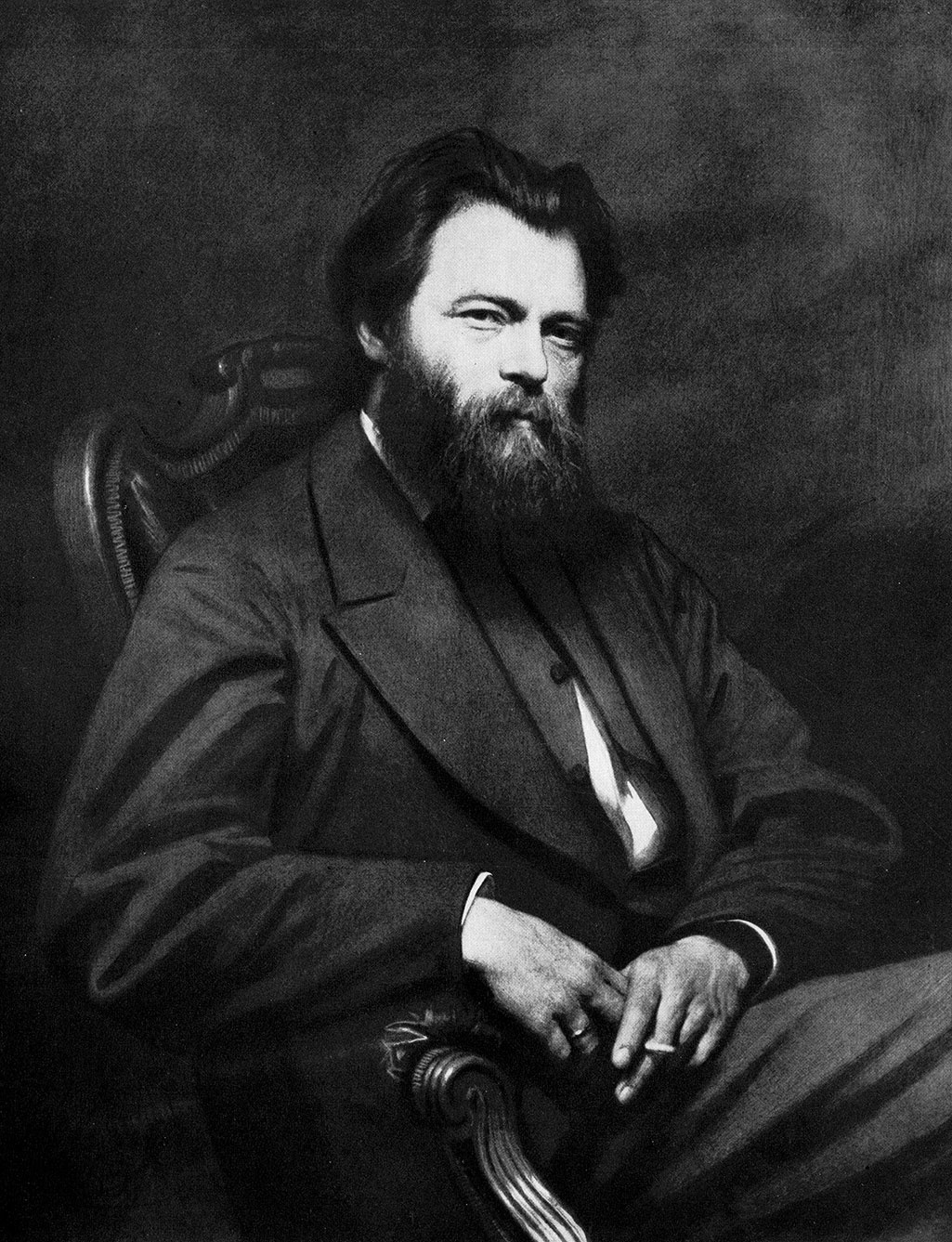

Portrait of the artist Ivan Shishkin

1873, 110.5×78 cm

Once the artist was mistaken for a "general, not a painter". Shishkin’s mother, Daria Romanovna, first visited the big city in her old age. When Ivan was little, she was very angry at his hobby, reproached that instead of doing something efficient he was doing "dirty paper", but in commerce he was showing marvellous "dementia". However, when in 1850 a terrible fire broke out in Yelabuga, first of all Daria Romanovna took her husband’s manuscripts and books, as well as notebooks and drawings of her son, out of the fire. And when he returned to his home with the medals from the Academy, and eventually with the glory of the main Russian painter, his mother changed her attitude. For that, Ivan Shishkin had to finally become famous, get rich and bring his mother to visit him in St. Petersburg. She entered the house, looked around the walls hung with paintings in gold frames, assessed the situation and rebuked her son: "Oh, Ivan, Ivan! Why did you write to me as if you were some kind of painter, while you are a general". Daria Romanovna was firmly convinced that painters could not live so well.

Noon. In the vicinity of Moscow

1869, 111.2×80.4 cm

The Russian bogatyr Shishkin showed himself in Germany. The coveted Great Gold Medal of the Imperial Academy of Arts gave Shishkin the opportunity to make a retirement trip to Europe. Personal acquaintance with European trends allowed the artist to fully realize how dear the Russian landscape

and the Russian realistic school were for him. New art trends did not affect him, and Shishkin reacted with fervour to any attempt to discredit his native language, sometimes even with aggression unusual for his temper. Art critic Dmitry Uspensky described such a case: "…in one of Munich’s pubs, the Germans began to make fun of the Russians and Russia. Shishkin stood up. A quarrel began, ending in the crushing of a whole crowd of Germans. The case went to court, and there, as material evidence, a three-finger-thick iron rod bent into an arc by the mighty hands of the fighting Ivan Ivanovich, appeared. The court acquitted Shishkin, and the German artists carried him from the courtroom to the nearest pub, where they paid tribute to his fellow and kind patriot."

Portrait Of I. I. Shishkin

1880, 115×83 cm

Shishkin did not suceed in the teaching field. After the reorganization of the Imperial Academy of Arts, Shishkin was invited to lead a workshop on the Academy site. This caused a lot of disagreements in the Association of Travelling Exhibitions (as well as the general desire of a part of the Itinerants to establish relations with the Academy), there was a high drama. After much deliberation, the artist accepted the offer. But the gossip at the Association and the intrigue at the Academy spoiled his time. All his life Shishkin did not like gossip, backstage games, intrigue! He avoided them whenever possible, but sometimes there was no opportunity. At the same time, we cannot doubt Shishkin’s teaching abilities, by that time Andrey Shilder, Fyodor Vasilyev, Olga Lagoda (Shishkin's second wife), Efim Volkov and others were listed as his students. He often took his students to go on location at his own expense, in order to work without being distracted by the fuss. In the academic workshop, Shishkin was very strict, young ladies often left him in tears. But if he saw talent in a student, he supported him with all his might, helped with advice, and patronage, and money, if necessary.

Critics often contrast Shishkin and Kuindzhi, calling the former a master of drawing, the latter an unsurpassed colourist. There are certain grounds for such a comparison. The studios of these artists existed at the Academy at the same time, and Shishkin himself suggested Kuindzhi to unite so that he would teach students to draw, and Kuindzhi to colour. Arkhip Kuindzhi flatly refused and even stated that he found Shishkin’s method harmful for painting. In general, the relationship of these two artists was a very passionate story, they often quarrelled violently, after which they reconciled, but not for long, until the next skirmish.

Studying under Shishkin turned out to be more boring than studying under Kuindzhi. Kuindzhi gave students freedom, whereas Shishkin taught his class to make more and more perfect drawings from photographs in the winter. Gradually, many of Shishkin’s students moved to the other group, and Shishkin himself practically stopped coming to classes, bitterly claiming that no one needed his training there. Soon he left the Academy — both because of all these troubles, and for health reasons. However, in a couple of years he would again be offered the place of the head of the landscape studio. Kuindzhi no longer taught at the Academy at that time, his place was taken by Kiselyov. Shishkin agreed, but not for long time as well, this time his death intervened.

Critics often contrast Shishkin and Kuindzhi, calling the former a master of drawing, the latter an unsurpassed colourist. There are certain grounds for such a comparison. The studios of these artists existed at the Academy at the same time, and Shishkin himself suggested Kuindzhi to unite so that he would teach students to draw, and Kuindzhi to colour. Arkhip Kuindzhi flatly refused and even stated that he found Shishkin’s method harmful for painting. In general, the relationship of these two artists was a very passionate story, they often quarrelled violently, after which they reconciled, but not for long, until the next skirmish.

Studying under Shishkin turned out to be more boring than studying under Kuindzhi. Kuindzhi gave students freedom, whereas Shishkin taught his class to make more and more perfect drawings from photographs in the winter. Gradually, many of Shishkin’s students moved to the other group, and Shishkin himself practically stopped coming to classes, bitterly claiming that no one needed his training there. Soon he left the Academy — both because of all these troubles, and for health reasons. However, in a couple of years he would again be offered the place of the head of the landscape studio. Kuindzhi no longer taught at the Academy at that time, his place was taken by Kiselyov. Shishkin agreed, but not for long time as well, this time his death intervened.