it is only love and art that can justify a human being.

Thanks to Maugham we still take Paul Gauguin as he has been depicted by the author in his novel "The Moon and Sixpence".

Somerset Maugham wrote 21 novels, more than a hundred of short stories and dozens of plays. He traveled all over the world and visited Europe, America, Far East and islands in the Pacific ocean. He studied medicine and was recruited into the British Secret Intelligence Service. He undertook a special mission in Russia during the February revolution assisting the head of the Provisional Government A. Kerensky. The British Government made an attempt to hinder bolsheviks from taking power and to save Russia as its wartime ally. Though, the mission failed.

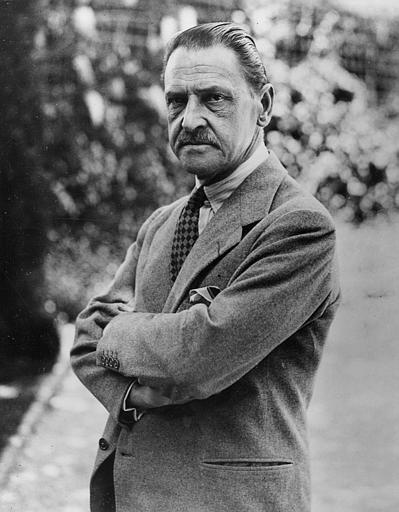

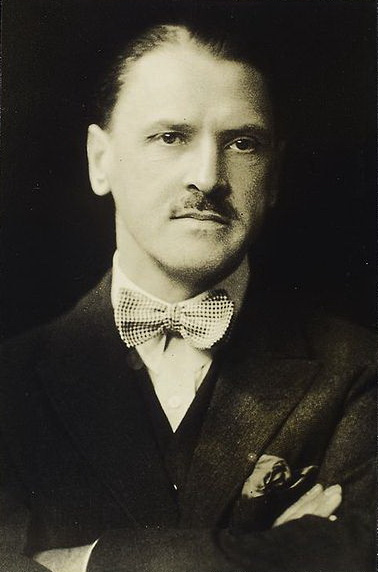

Photo: Somerset Maugham on the way from the Dorchester Hotel to the Buckingham Palace, July 14, 1954

In 1962, the Heinemann publishing house published a volume of picture plates accompanied with a short author’s story about the history of the collection Purely for My Pleasure.

On April 10 of the same year, 35 artworks from the Maugham collection were sold by Sotheby’s for GBP 524,000 with more than 2,500 bidders patricipating.

Somerset Maugham. Purely for My Pleasure, 1962

Maugham found the hut and discovered there three doors painted by Gauguin on their glasses. The children have scratched away the paintings on the two of the doors. He bought it from the owner for two hundred francs. However, in the evening, another man came and said the door was half his. He asked the writer for two hundred francs more which he gladly gave him and brought his valuable luggage to New York and then to France.

The Gauguin’s artwork "is very slightly painted, only a sketch, but enchanting. I have it in my writing-room."

Paul Gauguin. Eve with the Apple.

"On one of my visits, after he had greeted me, he said, ‘look what I did this morning.' He had engaged a model, and on sheets of paper, about nine by twelve, had made line drawings of her head. He had had them pinned up in rows, one row above another, on the wall that faced his bed. I did not count them, but I guessed that there were at least forty. It was an amazing feat for an old man lying in bed to fashion these drawings with such assurance and such distinction. I praised him and he was pleased with my praise. ‘But you must look at them again and again,' he said. ‘You must look at them and look at them, it’s only then you’ll see their power, the depth of thought in them, and their philosophy.' I could only see forty lovely drawings, but I had lived long enough to learn that the artist, no matter what his medium, is apt to see more in his production than is evident to the beholder. I nodded and held my tongue."

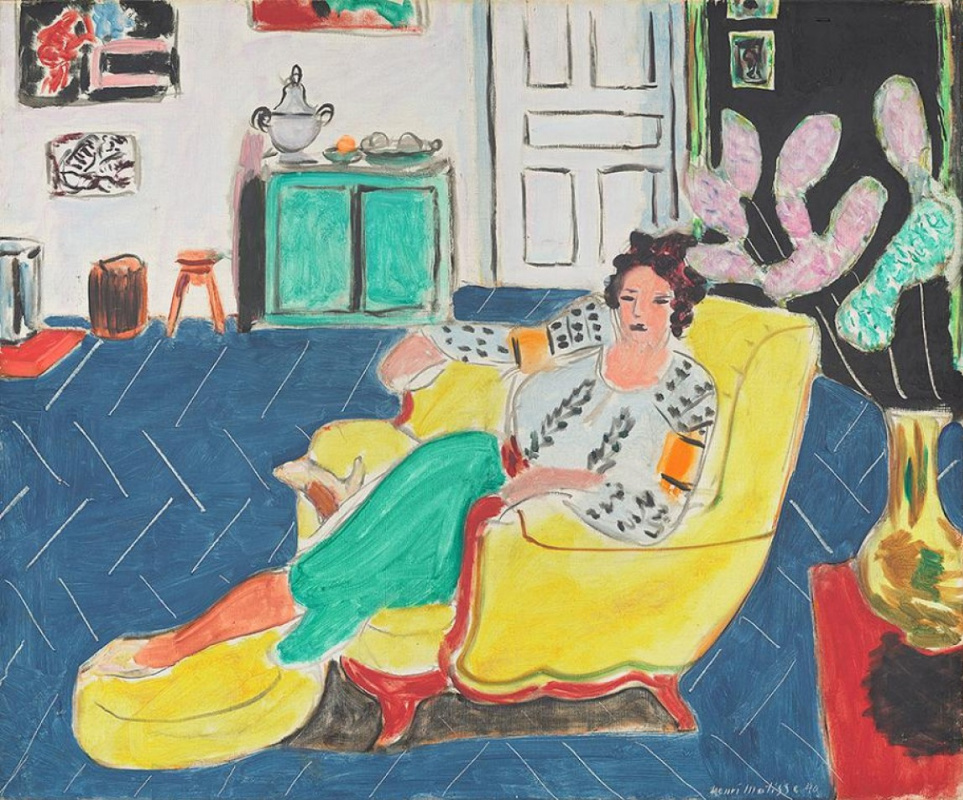

Henri Matisse, The Lady with a Parasol.

Mona Lisa was disappointment for Maugham

"When I was eighteen I entered St Thomas’s Hospital as a medical student. I took two rooms, a bedroom and a sitting-room, on the ground floor of a lodging house in Vincent Square. At that time the illustrated weeklies at Christmas gave their readers a large coloured reproduction [G. H. Barrable, Songs from Italy]. I got one of them, and as a modest decoration pinned it up in my sitting-room."

"On one of my vacations I took a trip over to Paris where two brothers of mine, both several years older than I, lived. I had read, re-read and read again Walter Pater’s essay on the Mona Lisa and on my first visit to the Louvre I hurried, full of excitement, past the pictures, till I came to Leonardo’s famous portrait. I was bitterly disappointed. Was this the picture Pater had written about with such eloquence and in prose so ornate?

I spent my mornings in the Louvre. I had no one to guide me. One young man, whom I met somewhere, an aesthete, said to me: ‘There's only one picture worth looking at in the Louvre, the Chardin. Don’t waste your time on all that rubbish they’ve got there. You’ll get much more art in the Folies Bergère.'

I was too shy to tell the young man that I thought Titian’s Man with the Glove a beautiful portrait and that Titian's Entombment had deeply moved me."

G. H. Barrable, The Songs from Italy.

"The most interesting person in this little group was an Irishman, sullen and bad-tempered, called Roderick O’Connor. He had spent some months in Brittany with Gauguin, painting, and I, already greatly interested in that mysterious, talented man, would have liked to learn from O’Connor what he could tell me about him; but unfortunately he took an immediate dislike to me which he did not hesitate to show."

"Then, by a happy accident, a play of mine which had been refused by manager after manager, was put on at the Court Theatre and was a success. It was followed by other plays, light comedies, with the result that I became in a modest way affluent. I had come to know Wilson Steer and used sometimes to go and see him. I bought two of his landscapes."

Wilson Steer, the Effect of Rain, Corfe.

Somerset Maugham became notorious for his bisexuality. That time homosexuals were persecuted in England. So, Maugham left London and moved to America and then to France.

"..for some time I had amused my imagination with pictures of myself in the married state, — wrote Maugham in his book The Summing up, — There was no one I particularly wanted to marry. It was the condition that attracted me. It seemed a necessary motif in the pattern of life that I had designed, and to my ingenuous fancy… it offered peace;… peace and a settled and dignified way of life. I sought freedom and thought I could find it in marriage".

Maugham did not hide his homosexuality even when he was married. In 1917, he married to Syrie Wellcome, they had a daughter Liza. He continued his sexual relations with men, and in 12 years they divorced.

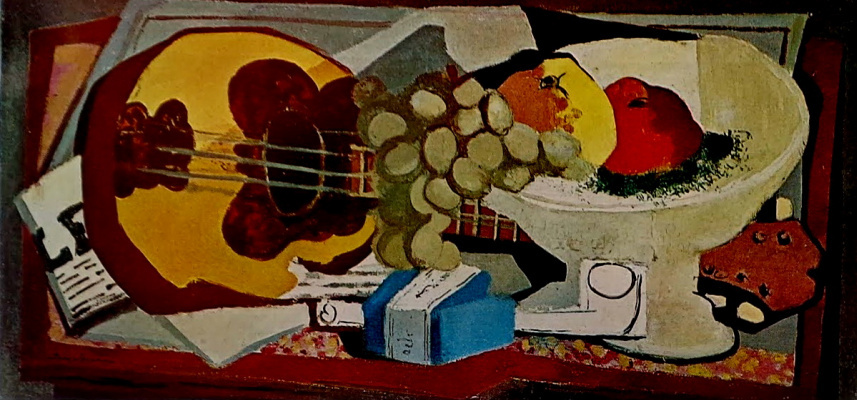

When Maugham lived in Paris he made the acquaintance of a lot of art dealers. Following the recommendation of one of them, Alphonse Kann, he bought the artworks by Jean Joveneau, who was a student of George Braque. That time he was starving. He also bought a painting by Fernand Léger.

"He was a jovial, friendly man, but, like all painters then, desperately hard up. I bought an abstract picture which Lèger called Les Toits de Paris. My friends mocked and asked me why I bought that fantastic composition."

Fernand Léger, The Les Toits de Paris. 1922

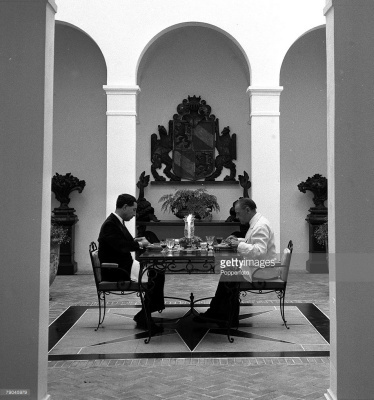

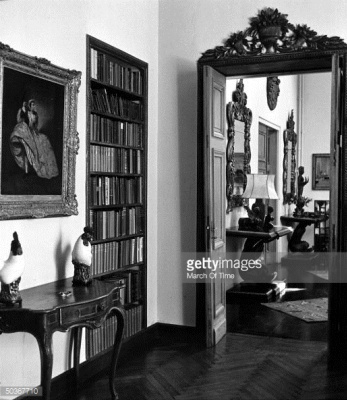

In 1926, the writer bought Villa Mauresque at Cap Ferrat on the French Riviera. It had been constructed for Félix Charmettant, the former missionary and chaplain to Leopold II, King of the Belgians; Villa La Mauresque became Maugham’s main residence until his death in 1965. When a lawyer proposed Maugham to include his daughter Liza in the will, the novelist refused and answered that he had read the King Lear by Shakespeare.

During World War II, after Riviera had been occupied by the Mussolini’s troops, Maugham abandoned the Villa by the last ship. When he backed after the War his villa had been ravaged; the art works disappeared (except the paintings, which had been removed to another location), porcelain lining of his swimming pool was broken, an unexploded shell was in his bedroom and his wine cell was empty. Maugham restored his villa and soon it became renowned for its lavish hospitality; La Mauresque received most of the celebrities who visited the Riviera: Winston Churchill, T. S. Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, Arnold Bennett, Ian Fleming and Jean Cocteau were among them.

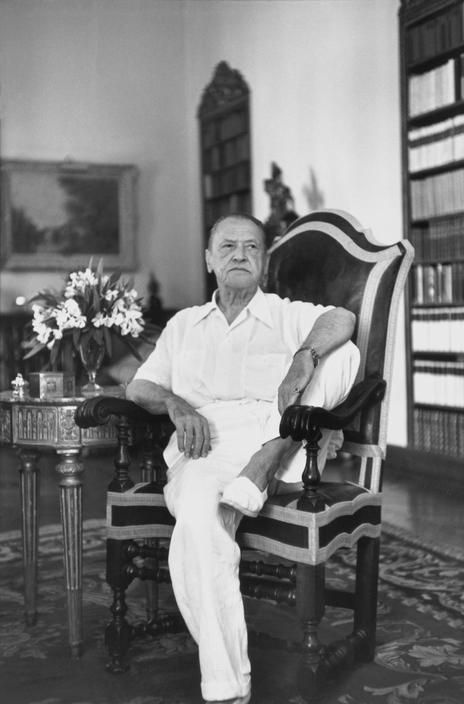

Somerset Maugham, Cap Ferrat, 1951, photo by Henri Cartier-Bresson

"I bought myself a house on the Riviera, the house I live in now, and brought my theatrical pictures from England. I hung some of them in my sitting-room and others on my staircase. For my dining-room I bought Provençal furniture and on the walls hung pictures by Marie Laurencin that I had bought some years before. The effect was pleasing and indeed was much admired.

One day Marie Laurencin called me up and said that she had heard how I had used her pictures and would like to come and see them herself. I asked her to lunch and she came… with a good-looking man who, I presumed, was then her lover. There were four pictures in the room. She looked at the first [The Rowing Boat] and smiled. ‘What a pretty little thing,' she murmured. At the second [Mother and Daughter] she said but one word: ‘Exquisite!' The third picture [Young Girl with a Fan] faced the door. She gasped. She turned to me as though I were responsible for it. ‘There can be no doubt about it,' she cried. ‘It's a masterpiece."

Somerset Maugham had a fellow feelings for the painter and did not accept her adoration of her own paintings as vanity; on the contrary, he liked her naivety. Some years afterwards, Marie Laurencin produced the portrait of Somerset Maugham and presented it to him.

Marie Laurencin, the Young Girl With a Fan.

Darryl asked Maugham’s friend George Cukor what would be the best way to thank the novelist for his job. Darryl suggested that it could be a golden cigar case. Cukor answered that Maugham had had it. Than Zanuck assumed he could offer the writer a car. The answer was the same; Maugham did not need a car as he had had it. Darryl was in despair and the painter suggested that the best gift for the writer could be an artwork.

Instead of the fee for his script (which had not been used by the Film Company) Somerset Maugham was offered to choose an artwork at the price of $15,000.

Maugham had never bought an artwork for such a price so he was thankful to Darryl Zanuck for such offer. He bought the Lady with a Parasol by Henri Matisse, A Winter Landscape, Louveciennes by Camille Pissarro, and the View Outside Paris by Stanislas Lépine.

Camille Pissarro, A Winter Landscape, Louveciennes. 1874

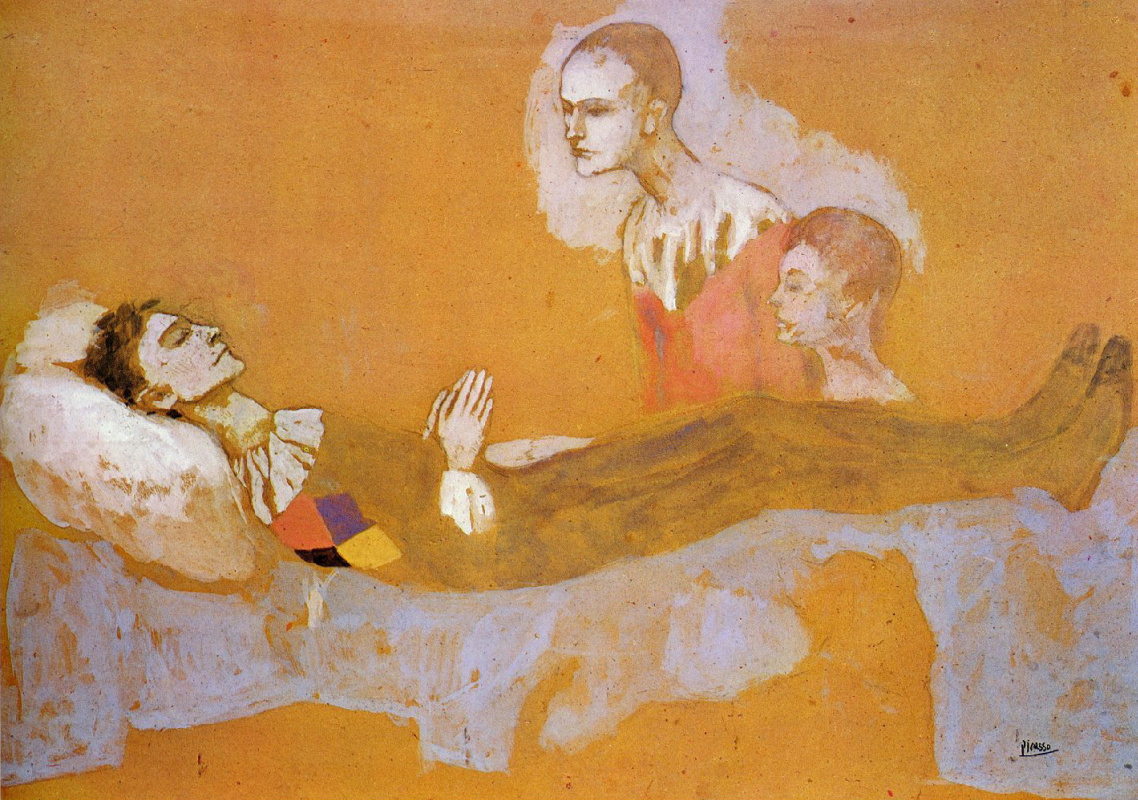

"On my last visit to New York I had seen at a dealer’s Picasso’s The Death of Harlequin and was fascinated by it. It was a deeply moving picture. But it cost a lot of money and to restore my house had proved expensive. I could not afford and returned, disconsolate, to France. But I kept thinking of the picture; I wanted badly to possess it. It was a lovely thing. I felt I should regret it all my life if it was snapped up by somebody else.

At last I said to myself, ‘damn the expense,' and made the dealer an offer. I knew that he had a monumental picture of a standing woman, also by Picasso [La Grecque], which was not an easy object to dispose of and I was aware that he had had it for some time. I had the exact place in my hall to put it and, thinking it would tempt him, included it in my offer. To my delight he took it and the two pictures eventually reached me."

Pablo Picasso, Standing Woman (La Grecque)

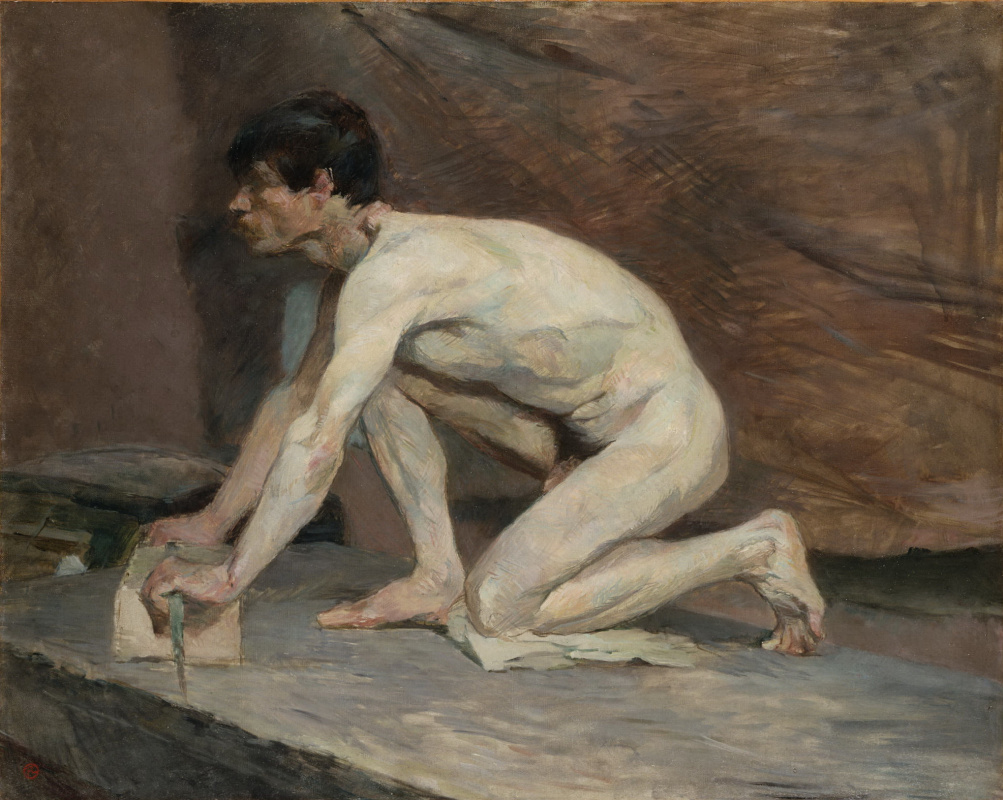

Somerset Maugham often asked the experts who came to see his pictures whether they could guess who had painted it. Only one of them could. "My old friend, Sir Kenneth Clark, looked at it for two minutes and then said, ‘No one could have painted that head or that foot but Toulouse-Lautrec,' and of course he was right."

Maugham also collected theater paintings and artworks related to the theater. He highly estimated his collection and intended to give it to the National Theater in London. He moved his collection to the Theater in the 1950s, though that time the Theater was under construction and his collection was taken by the National Theater after the writer’s death. When a temporary exhibition was held almost 30 years ago, four paintings were stolen, and one never recovered. So it was clear that the National Theater would have a lot of troubles to keep the paintings safe and they were given to the Holburne Museum or Art in Bath.

Bannister and Suett in George Coleman the Younger’s 'Sylvester Daggerwood'

The book The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham by Selina Hastings was published not long ago. The writer became the first biographer who had an access to the private correspondence of the famous novelist and playwriter. In one of her interviews, Hastings shared her impression from the nature of the writer and his hidden features of the character.

According to Selina Hastings, Maugham intended to hide his inner world; in reality he was a passionate, sensitive and emotional person. He positioned himself completely different as a cynical personality as if there were nothing sacred with him. That was far beyond the truth. In reality he was moral, courageous and reasonable. Nothing in a human nature could surprise him.

The biographer told that at his old age the writer suffered with a thought disorder. That could likely explain his odd behavior that time. In 1962, Maugham disclaimed Liza as his daughter and intended to disinherit her. He made an attempt to adopt his secretary Alan Searle and to settle his property on him. His daughter filed a lawsuit and the court ruled in Liza’s favor, she could not be disinherited and the attempt of adoption of the secretary was invalid.

Graham Sutherland, the Portrait of Somerset Maugham, 1949