Maxim Kantor, a Russian painter, writer, and essayist, in his book 'Thistle. Philosophy of Oil Painting' wrote these lines about Rembrandt, "Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn was a very sad artist. Only in the beginning had he an easy life, then it went hard, and he did not paint laughing people in his maturity."

Saskia van Uylenburgh

This is Saskia van Uylenburgh, the youngest daughter of Leeuwarden burgomaster and the beloved wife of a young painter from Leiden, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. On the portrait above she makes an ambiguous gesture, chaste and seductive at the same time. She covers her breast with one hand and offers a daisy to the artist with another one — a symbol of an unbreakable marital fidelity.

Isn’t it strange? Leeuwarden is in the north of the Netherlands, Leiden is in the south. She was a purebred noblewoman, albeit from a province, and he was a son of a miller, grinding and delivering to a marketplace malt, not flour. Where did they have a chance to meet?

Hendrick van Uylenburgh returned from Poland where his family fled to because of religious persecution, and set up as an artist in Amsterdam. He opened a studio, employed other artists, and started selling their work as well as his own. His workshop shortly became well-known as a good place to by a good picture. In 1631−32, Hendrick took Rembrandt into his studio and, as a wily merchant, used his chief talented painter as a poster boy in his entrepreneurship.

Business was blooming. Portraits made by Rembrandt was so popular that he, supported by van Uylenburgh, took liberties to set unbelievable prices. The portrayal of a human face painted by the young genius costed 50 florins, and the author could demand for a full-size portrait up to 600 florins! Never before or after that most successful period in Rembrandt’s life, has the artist ever made such progress in a society. Van Uylenburgh and Van Rijn came out together a lot, and it was a kind of natural for Rembrandt to ask Hendrick for his niece’s hand. At that time, Saskia came to Amsterdam from her Friesland and calmly and quietly lived in a house of Jan Cornelis Sylvius, a preacher of the Dutch Reformed Church, who was husband to her elder cousin, Aaltje.

In the absence of Saskia’s parents, Rembrandt asked her sisters and brothers-in-law for Saskia’s hand and discussed details of their upcoming engagement in May 1633. Apparently, it was important for him to make a positive impression on these people. The Uylenburghs were members of the Mennonite community, one of the most pacifist and pious Protestant denominations. Rembrandt did not want to appear an idle spendthrift or a bohemian wastrel. Basing on their consent, he has succeeded at that moment.

Portrait of Saskia in a Straw Hat (or Portrait of Saskia as a Bride) is stored in a Staatliche Museen in Berlin. It is made by silverpoint, a small fine rod of silver inserted into a wooden rod, on a specially prepared parchment. The inscription on it was added by Rembrandt at least a year after the drawing was made. It reads: "This was drawn after my wife, when she was 21 years old, the third day after we were engaged 8 June 1633." Over time, light silver lines have darkened and we enjoy the portrait in brown-black tones. Nonetheless, there is probably no image of Saskia made by Rembrandt as fresh and tranquil as it is in this etching.

We cannot consider their marriage to be idillic, for Rembrandt most likely has not received his parents' blessing. And in three or four years, it was the Uylenburghs family’s turn to be offended and outraged. Their brother-in-law, Rembrandt the artist, painted his self-portrait with Saskia that was too far from the image of аsceticism and piety.

His famous 'Prodigal Son in the Brothel,' which is kept in Dresden, has a definite portrait resemblance between Rembrandt and the young fellow with his back to viewers. And as he turns around to us, we see him laughing and reaching his hand out with a glass of wine as if inviting us to immediately partake his celebration. There are plenty of dishes on the table, including a roasted peacock, which stands here for the rampant luxury. And there is a harlot with the face of Saskia on the fellow’s lap. We should not forget that it’s not the image of an artist but of a prodigal son, a biblical character. Rembrandt would also show us what happened to him later.

This picture was made at the juncture between genre and history paintings and it has done Rembrandt a sorry service. His first biographers started writing about the artist basing on it. They turned him into a lecher, boozing and wasting his time and money, ignoring the fact that the 'Prodigal Son in the Brothel' might not have had any roots in the author’s biography. Even if it had, Saskia was totally safe. Even in such a boozing air she keeps stern and serious expression on her face.

Rembrandt has made his etching Death Appearing to a Wedded Couple from an Open Grave in 1639. The ominous allegorical significance had the artist put in it. A beau, wearing a beret with a plumage (which Rembrandt usually wore himself in his self-portraits), freezed by the edge of the grave, and his lady, with her hair reminding us of Saskia’s curls, handed her flower not to her beloved man, as Saskia had offered a daisy to Rembrandt before, but to a death in front of her. Death is traditionally rendered here as a skeleton. Its hand, outstretched ardently, is ready to take somebody else to the grave. And sure enough it would have happened this way.

Saskia passed away in 1640, aged 29. Rembrandt did not buried her near their kids in Zuiderkerk, but carried her corps to the Oude Kerk. They’ve made their wedding vow in there, and his brother-in-law Jan Cornelis Sylvius still served there as a preacher. Rembrandt hoped that his pious prayers would make Saskia`s afterlife easier since they could not support her here on Earth.

When Rembrandt came back home to his deserted house, which actually had put him into debts three years before, and therefore сaused Saskia’s concern and reasoned her scolding him, the artist took off his wife’s portrait painted 10 years before in order to repaint it. This portrait, produced by Rembrandt in the beginning of their marriage, depicted Saskia wearing a red hat and standing in strict profile. The copy of the first version made by Govert Flinck has survived. It helped the researchers to found out that the portrait had looked different before.

Saskia’s blouse and her outward garments were barely defined by Rembrandt in the fist version. Her dress was not embroidered with a plentiful decoration. There was no plumage on her scarlet hat and no mink coat on her shoulders. The painting was much more simple and unsophisticated. In the repainted version, though, Rembrandt transformed his beloved woman into a Renaissance princess, he wrapped her in fur and velvet and put the expensive jewelry and accessories on her, but he deprived her of something essential and important. In contrast to her other portraits, Saskia seems extremely beautiful in this one, although she is cold and distant. Simon Shama thinks that here Saskia turned into a shining jewel, bending under the mass of pearl necklaces, and disappeared in a cabinet of curiosities of her husband along with his other treasures forever.

It might be the way Rembrandt said farewell to his wife and paid his last respects to her in such a way.

Geertje Dircx

What about her face? We fail to find it in the artworks by Rembrandt. We have never seen it, just her figure. In one of the artist’s drawings she is depicted standing on the porch of the house speaking with someone in the street dressed in a peasant frock typical for the northern provinces. This portrait by Rembrandt has disappeared. (According to Paul Dearg’s book 'Rembrandt').

Unfortunately, she evidently existed in Rembrandt’s life — nobody could avoid the reality.

Titus was nine months when Saskia died. His father, who loved the boy most of all, was very busy working most of his time at the workshop. Important patrons stayed away from Rembrandt confused with the growing naturalism of his portraits, but the artist was stubbornly and fanatically seeking his own artistic manner. Rembrandt lost himself in work.

We could only assume that it was either just a love sick, which made the artist neglect the roughness of their relations and nonmorality of such kind of a gift, or just the desire to get rid of his deep sorrow, still hurting and painful. Though, many times later on Rembrandt would be sorry for this.

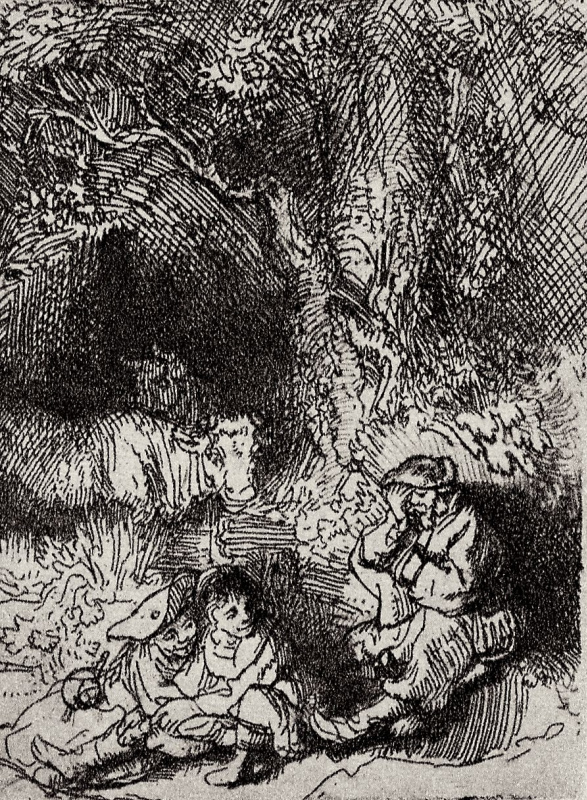

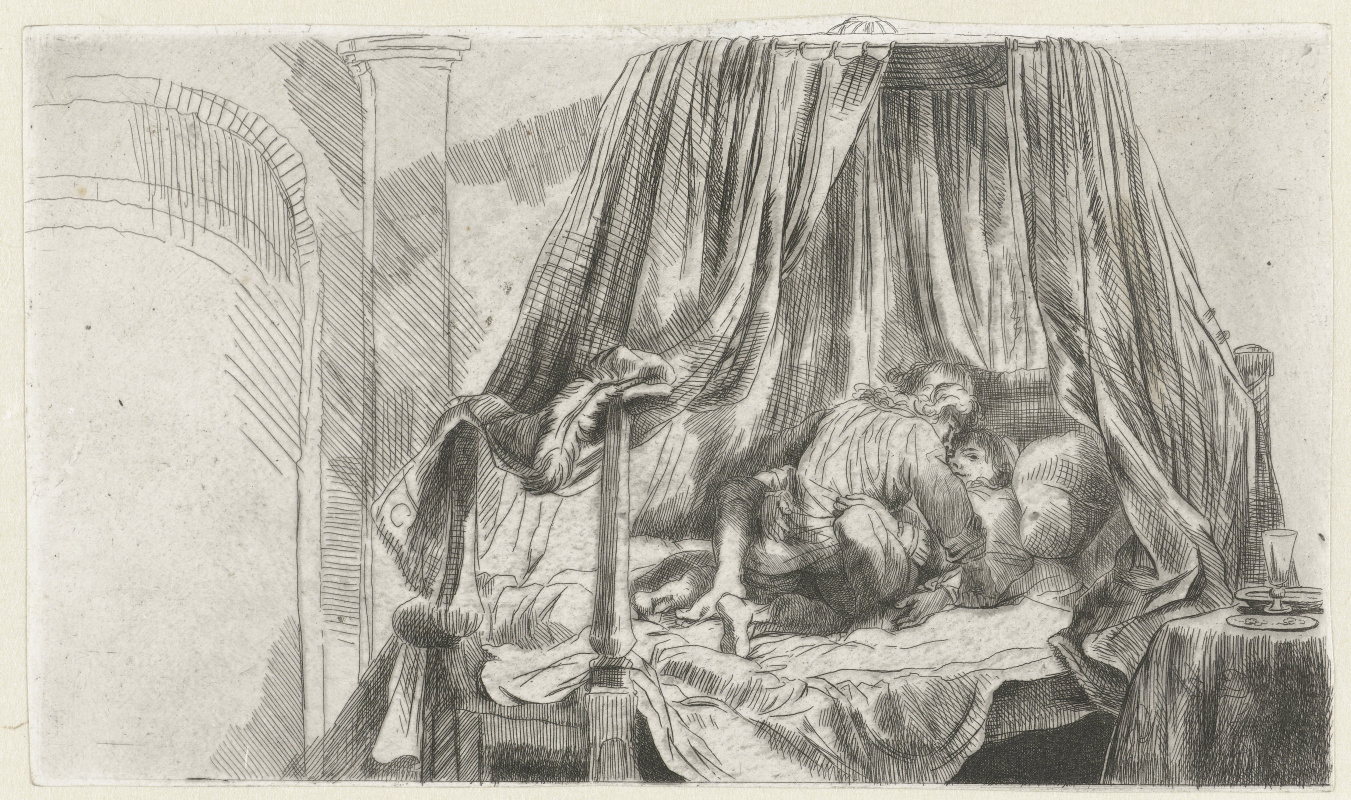

He evidently enjoyed his passion; the erotic theme is explicitly revealed in his etchings of the time of his love affair with Geertje (The Sleeping Herdsman, the Monk in the Cornfield, ‘Ledikant' or ‘Lit à la française'). We cannot but mention the collection of prints Rembrandt had been acquiring during his life, which included classical examples of erotic art, like Agostino Caracci’s erotic engravings or illustrations by Marcantonio Raimondi and Giulio Romano to Pietro Aretino’s book 'Sonetti lussuriosi'. These erotic etchings by Rembrandt do not cozy up to mythology like those of his predecessors, but according to Simon Schama they depict a heavy awkwardness of the animal like coition. It looks like Rembrandt did not intend to elevate his way of life at that period of time but realistically depicted his love affair instead, which was just sex, coition and no-nonsense relations.

Art historians are not unanimous in interpreting her act. Paul Dekarg assumed that Geertje treated Titus as if he had been her own son to become an integral part of the family; making sex with her, Rembrandt was not going to marry Geertje keeping in mind the testament of Saskia. He could loose all his fortune because of his re-marriage, so he did not intend to ignore this. Simon Schama assumed that Rembrandt’s attitude to Geertje made her act in such a way. The artist might have felt guilty because Titus could loose the jewellry of his mother, which he had to inherit instead of his father`s lover. It is known that in the late 1640s young Hendrickje Stoffels obtained work as Rembrandt’s housekeeper, and having lost his interest to Geertje the artist switched his attention to a 23-year-old beauty.

He was going to separate with Geertje peacefully and offered her annual alimentation of 160 guilders (under the official contract), and she agreed first. Though, on leaving Rembrandt she appeared to be absolutely alone and changed her mind feeling cut to the heart. First, she pawned Saskia’s jewellries and then filed a lawsuit against the artist.

Rembrandt obediently visited the hearings where Geertje publicly testified that the artist had promised to marry her, and he had even given her a ring as a present, that it had not been once that he made sex with her. She insisted on either marriage or alimony regardless the alimony agreement she had signed before, under which she had to get 160 guilders annually. In the court she demanded more. The court hold that the sum of the alimony should be 200 guilders. She felt hurt and demanded more.

Then Rembrandt’s revenge was brutal, the artist’s reputation had been dented and he had nothing to loose. He bribed his neighbours to talk ill of Geertje. He managed to prove her disability (he accused her in mental disorder and evil life), and the woman was confined to an insane asylum for women; there were a lot of such kind of prisons in Holland at that time. Severe austerity reigned there; smell of leach and cooked peas was everywhere. The prostitutes and the homeless were reformed there working hard, their fingers aching after long hours working at the spinning wheels. Their souls and ears accepted nothing but endless instructions of their supervisors.

Geertje was released in five years (Rembrandt wanted her to be sentenced for 11 years of imprisonment). She was absolutely ill. In the mid-1650s she died without a chance of enjoying a cruel destiny of her offender; Rembrandt lost his patrons and crashed.

In the middle of the XX century Yuriy Kuznetsov, a Russian art expert from the Hermitage Museum carried out an X-ray scan of the Danaë by Rembrandt. There were some doubts as to this painting, which is famous for its stunning sensuality and erotism. Rembrandt produced it in about three years after his marriage to Saskia, he depicted a wedding ring on Danaë's wedding finger. It could be reasonably to assume that a model for this seducing and tempting image could be the wife of the artist. At the same time the sharp features of the lady in the painting are not alike the features of Saskia — plump, rounded and so familiar to us from the other portraits by Rembrandt.

Hendrickje Stoffels

The other lady, Geertje by name, could not decide whether she was a servant in the house or a housekeeper. She and Rembrandt were constantly quarreling, and the reasons were different: either the lunch was unbearable, or a bedsheet was not clean enough; a lot of faults could be invented when passion calmed down and they were not able to become friends.

Shortie Stoffels was not afraid. She was a daughter of a sergeant. All her brothers served in the army and her sisters married to the army men. Hendrickje was also a steadyfast tin soldier. When she had to testify upon a trial of the fact that Geertje Dircx had agreed to 160 guilders annually, Hendrickje did not hesitate to do that.

"Hendrickje was a modest common servant who became a lover of Rembrandt. She was a model for Rembrandt’s drawings and some paintings, for instance, for his 'Woman in Bed'. His artworks demonstrated sexuality of the model and the artist was evidently fascinated by her, depicting the details of her young flesh. Rembrandt had never hidden his relations with Geertje from Hendrickje, and she had never been boring and quarrelsome."

In 1654, Rembrandt began painting his Bathsheba at Her Bath (or Bathsheba with King David’s Letter) the most beautiful nude in his oeuvre according to the common opinion. Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah, a general of King David’s army, is sitting nude on pure white drapery, with a letter from her lover King David in her hand. She appears to be lost in thought. On the contrary to the previous traditional images of Bathsheba (including Rubens’s) depicting her light-minded and flirting: Rembrandt reveals sorrow in the subject’s face. She knows that she is pregnant; her husband has been in the army for several months; very soon her sin will be disclosed.

She had been ignoring the rumors behind her back for a long time. The neighbors called her a prostitute and a fallen woman because of her relations with the artist. By 1654, the couple had faced a serious problem. Hendrickje became pregnant at the beginning of the year, and in June her pregnancy became noticeable; Hendrickje and Rembrandt were summoned to the Church council.

Rembrandt was not charged because he was not a member of the Reformed Church. Hendrickje’s situation was much more serious. The charge of the Church council was "that she had committed the acts of a whore with Rembrandt the painter". She admitted this and was banned from receiving communion. The verdict of the Church was that the woman had to be convicted of sin and quit her illegal relations with Rembrandt.

In October 1654, being faithful and courageous in her love to the artist, Hendrickje gave birth to a healthy child. It was a girl, the third daughter of Rembrandt, and he gave her a name of Cornelia without any hesitation. This daughter of Rembrandt survived, unlike both Saskia’s babies who had died before they become one year old. At least, she was known to get married in 1670, give birth to two boys, Rembrandt and Hendrick.

Hendrickje Stoffels died in 1663 at the age of 38; she devoted 15 years of her life to Rembrandt. The painter buried her and outlived this lover of him as well. Just mind it when you are looking at his late self-portraits with the face of a hard bitten and experienced old man who loved and suffered a lot.

![Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. The beggars` figures and the woman in bed [Saskia during her illness] Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn. The beggars` figures and the woman in bed [Saskia during her illness]](https://arthive.com/res/media/img/oy800/work/291/460935.jpg)