Let's figure it out: could it be that the earring in the famous 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' was not really a pearl?

This painting belongs to the most recognizable images of the modern culture. It leaves the viewer fascinated with beauty, technique, dramatic style, lighting, and a subtle feeling of the moment’s transience. Well, but why does the jewel in the girl’s ear look more like a silver one rather than a pearl? If it’s a pearl, why make it so big? Let’s try to figure it out.

The Origin of the Name

Let’s start with the painting’s title. One may think that there is a clear indication of the pearl in the very name of the picture — after all, the author knew what he was depicting, didn’t he? Well, it’s not that simple. The fact is that Jan Vermeer — similarly to other artists of that time — would not entitle his works. Most often the artworks were named by solicitors who made registers of their clients' property. Thus, an inventory from 1676, compiled after the artist’s death, includes ‘two tronies in Turkish style' (in other words, two portraits-fantasies). The work in question was, most likely, one of those two. Later, it was labeled as 'Girl in a Turban' and 'Head of a Young Girl'.

'Girl with a Pearl Earring' became the official name in 1995, when the owner of the painting, the Royal Mauritshuis Gallery, the Hague, chose it among many other variants to be listed in the catalog for the Vermeer exhibition in Washington DC. That was its English name, and the Dutch one was even more unambiguous: Meisje met de parel (Girl with a Pearl). Four years later, the writer Tracey Chevalier settled the Girl with a Pearl Earring title by writing the eponymous novel which was made into a movie in 2003 starring Colin Firth and Scarlett Johansson.

As you can see, the name of the painting can not be the starting point for our research. However, before looking for the clues on the earring itself, we should digress for some significant prerequisite circumstances.

A still from the film Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) directed by Peter Webber

A Tiny Bit of History

Jan Vermeer left no diaries or records of other sort behind. He was scarcely mentioned in the letters of his contemporaries. It is known that Vermeer was a wealthy man, but he died in extreme poverty. His widow had to sell a few paintings to a local baker to pay the bills.Vermeer was born in the Dutch city of Delft in 1632. His father was an art dealer and an inn owner. He inherited both businesses and created art himself. Nowadays, only 33 paintings are confirmed as the works of artist himself.

Such a small legacy can be explained by several reasons. Firstly, the artist lived only up to 43 years; secondly, he painted only two artworks a year, paying much attention to every detail. In addition, one should note the high cost of paints and dyes, a large family (11 surviving children!), and the need to attend to his businesses.

Apart from that, Vermeer’s art had remained unappreciated for more than two hundred years, thus many of his paintings could have been repainted, discarded or put to fire.

Vermeer created Girl with a Pearl Earring in about 1665. As already mentioned, it was a tronie — that is not a commissioned portrait of a particular person, but a studio work depicting an anonymous model wearing an exotic outfit or an unusual expression. In 1881, the picture was acquired at an auction for only 2.3 guilders (about 27 US Dollars in today’s purchasing power). After the death of the buyer, the art work was acquired by the Mauritshuis. It was cleaned and restored in 1915, 1960, and in 1994 — the latter date being the most important one here.

Let’s Return to our Mystery

First of all, let’s examine our objet d’art as closely as modern technologies allow. Consider this: the earring looks silvery and reflects light as if it were made of metal or coated in metallic paint. Besides, it would be too huge for a pearl!

Girl with a Pearl Earring, detail.

Before the restoration of 1994, the art lovers had seen something completely different. The layers of the old varnish had colored the painting in yellowish shades, and some details were completely dark. In addition, the upper layer of the varnish had been found to contain a black pigment; it was apparently mixed in to alter the tone of the picture. On the lower glare of the earring, there was a small bright spot, which, as it turned out, had not been a detail of the original picture. It was a drop of paint that got there during the earlier restorations. After its removal, the jewel regained its original even glow.

Left: the screenshot from the Girl-with-a-pearl-earring.info website showing the clearly visible drop of paint (above) removed after the restoration (below).

In general, it would not be surprising at all if some clerk in the past centuries wrote the title 'Girl with a Pearl Earring' after a cursory glance at the picture and went home with a feeling of a job well done.

Pearl? Porcelain?

Well, it seems that we are close to solving the mystery. What about the size of the decoration, then? Can natural pearls be that large? Strange as it may seem, yes. At the moment, there are two known giant pearls. One of them is called Pearl of Lao Tzu or The Pearl of Allah. It was found in 1934 on the Philippine island of Palawan: its weight is 6.37 kg, and its diameter is 23.8 cm. The record belongs to an object that weighs 34 kilos and measures 67 cm in length and 30 cm in width. In 2016, the authorities of the Philippines reported that a certain fisherman had discovered it 10 years before that.

The largest pearl in the world weighing 34 kg. Photo via BBC.

Theoretically, such huge pearls can be split into pieces and polished, but they are very rare and cost a fortune (for example, Pearl of Lao Tzu is evaluated at 40 million dollars; the second, nameless so far, is worth about 100 million). It is even less likely that the pearl on Vermeer’s painting was artificial. The first documented success in pearl cultivation dates back to 1761 (approximately 96 years after the portrait in question had been created), and the first official patent for this process was issued only in 1916.

Another option for the material might be porcelain. As we know, porcelain jewels are almost exclusively cameos, while records indicate that this ceramic material had been used to make glazed and painted beads for necklaces, brooches, and earrings.

Let’s scrutinize the details of other paintings by Vermeer: Woman with a Pearl Necklace and A Lady Writing a Letter. One can’t help but notice that the silvery jewels look very similar to that in Girl with a Pearl Earring. Perhaps, it was a family treasure, and Vermeer used it as a prop.

The jewel in the right ear (the one that is further from the viewer) of the lady writing a letter is obviously too large for a usual pearl.

At the same time, both paintings, in addition to earrings, depict pearl strings and the light from beads is reflected not evenly — just as the light should reflect from natural jewelry; and their color is the color of pearls. Obviously, Vermeer did know how to paint pearls, but the earrings are different from the beads, because they shine in a certain metallic tint.

By the way, there are large "pearl" earrings on the female characters of other Vermeer’s paintings, for instance 'Woman with a Lute' and 'Girl with a Red Hat'.

The Argument of Professor Icke

Three years ago, Vincent Icke, Dutch astrophysicist and amateur artist from Leiden, published an article in the New Scientist, arguing that the character of Girl with a Pearl Earring was not wearing pearls. Here is an excerpt from the publication in November 2014 issue:"…The main doubt is brought by the reflection of the white collar at the bottom of the bead. If it was a pearl, it would consist of thin layers of calcite, which scatter and refract light of different lengths," Icke wrote. "It would create the famous soft white — pearl-like — shine. Instead, we see a bright glare in the upper left part of the decoration and a reflection of a piece of clothing at the bottom…" Professor Icke believes that the earring was made of "silver or, perhaps, polished tin".

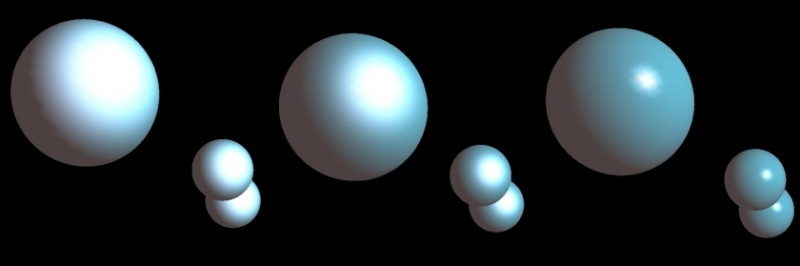

Reflections on spheres from an adjacent light source. Left — completely dispersed; right — completely reflected; middle — dispersed by 40%. Photograph by Vincent Icke, Dutch Journal of Physics.

Here’s how the Mauritshuis gallery responded to the astrophysicist’s article at its official website:

"Vincent Icke’s article confirms what we wrote about Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring some time ago… The museum’s description of the painting also mentions the unusual size of the pearl. Vincent Icke came to the same conclusion, but through a different method of understanding and study

. Mauritshuis took great interest in his results. This provides an illustration on why the Dutch paintings of the seventeenth century are so interesting: everything they depict is not what it seems at first glance."

Mauritshuis did write earlier that the jewel in the ear of the Vermeer’s girl was not a real pearl. In fact, just like the turbans, "pearls" were not part of an everyday dress of the Dutch women of the seventeenth century. Quentin Buvelot, chief curator of Mauritshuis, and curator Ariane van Suchtelen noted, "The pearl in the girl’s ear is surprisingly large. In our time, most of the jewelry is grown artificially, but in the seventeenth century they used to wear the ones naturally formed in the shells of mollusks. Large pearls were a rarity and often ended up in collections of the richest people on the planet. Widespread in the seventeenth century were cheaper glass pearls, usually from Venice. They were made of glass, with a matte finish given artificially. It is possible that the girl is depicted with such a handmade pearl".

Mauritshuis did write earlier that the jewel in the ear of the Vermeer’s girl was not a real pearl. In fact, just like the turbans, "pearls" were not part of an everyday dress of the Dutch women of the seventeenth century. Quentin Buvelot, chief curator of Mauritshuis, and curator Ariane van Suchtelen noted, "The pearl in the girl’s ear is surprisingly large. In our time, most of the jewelry is grown artificially, but in the seventeenth century they used to wear the ones naturally formed in the shells of mollusks. Large pearls were a rarity and often ended up in collections of the richest people on the planet. Widespread in the seventeenth century were cheaper glass pearls, usually from Venice. They were made of glass, with a matte finish given artificially. It is possible that the girl is depicted with such a handmade pearl".

Now it would seem, that the question can be answered unequivocally? Not at all.

Objections

Responding to the arguments of Vincent Icke about the size of the earring, Ariane van Suchtelen pointed out that the picture was rather a play of imagination than an actual portrait. A large jewel could be just an artistic exaggeration. "Icke is definitely right, if one accepts that reality is represented on the painting as it was,' said the curator. She insists this work to be partly an invention, "I'm sure Vermeer intended to create a bright illusion of a pearl."It is believed that the famous The Little Street of Delft is also partly Vermeer’s imagination. However, Professor Frans Grijzenhout at the University of Amsterdam claims to have discovered it on the records of the Dredging Register in Delft dated 1667.

Ariane van Suchtelen is supported by another major specialist in Vermeer’s legacy — Arthur K. Wheelock Jr, curator of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. He believes that Vermeer was more interested in the impression of the artwork than in the ‘accuracy of depiction,' and that’s why the pearl is so large and brilliant. After all, this is the picture’s principal detail, and if the artist had meticulously depicted the pearly surface, it would have had ‘a bit boring' look. "I’m not sure you’d want to get a large fuzzy object right in the middle of a painting," says Wheelock. "We must remember that he was an artist, not a photographer or an expert on pearls. This was not up to his profession."

In turn, Vincent Icke does not give up, "If a person declares that this was a pearl, but Vermeer painted it as silver bead, I’ll find their reasoning to be very controversial." Nevertheless, the astrophysicist admits that this issue will never be settled for good. "This man has been dead for four centuries. I fully recognize that an experiment would not prove anything definitely in this case," concludes the scientist.

In turn, Vincent Icke does not give up, "If a person declares that this was a pearl, but Vermeer painted it as silver bead, I’ll find their reasoning to be very controversial." Nevertheless, the astrophysicist admits that this issue will never be settled for good. "This man has been dead for four centuries. I fully recognize that an experiment would not prove anything definitely in this case," concludes the scientist.

Whatever material the jewelry of our character was made from, the masses still remember her as Girl with a Pearl Earring. If you do not like this title, you can refer to it differently. Let’s say, you can call in the Dutch Mona Lisa.