One day, Whistler entered the Parisian cafe chin high, monocle in his eye, frock-coated and top-hatted. Degas, seeing him from behind the table, exclaimed: "Whistler, you have forgotten your muff!"

In one of the conversations about Whistler Degas joked: "You cannot talk to him; he throws his cloak around him — and goes off to the photographer." And in another one, telling his interlocutor about his recent meeting with the American, he casually remarked: "He used his curls to flirt the same way he used his brushes."

This did not prevent the artists from remaining friends for a long time. When Whistler consulted an Austrian collector who came to Paris to get some new paintings, he said: "There are only me and Degas!"

He did not let journalists on his threshold, and preferred not to tell his personal secrets and family affairs to those of his friends who knew how to write. Nobody could be trusted — every careless word could be the reason for a new scandalous article.

When the English writer and poet George Moore decided to write an article about Degas, the painter was indignant: "Leave me alone; you didn’t come here to count how many shirts I have in my wardrobe?" "No, but your art. I want to write about it." "My art, what do you want to say about it? Do you think you can explain the merits of a picture to those who do not see them? Dites? I can find the best and clearest words to explain my meaning, and I have spoken them to the most intelligent people about art, and they have not understood; but among people who understand, words are not necessary. You say humph, he, ha and everything has been said. My opinion has always been the same. I think that literature has only done harm to art. You puff out the artist with vanity, you inculcate the taste for notoriety, and that is all; You do not advance public taste by one jot … Notwithstanding all your scribbling it never was in a worse state than it is at present. Dites? You do not even help us to sell our pictures. A man buys a picture not because he read an article in a newspaper, but because a friend, who he thinks knows something about pictures, told him it would be worth twice as much ten years hence as it is worth today… Dites?"

Still, George Moore wrote the article and, to his own harm, mentioned rumours in one small paragraph. They said, wrote Moore, that one of Edgar Degas' brothers went broke and the artist paid all his debts. After that article, Degas ceased communicating with Moore.

Today, George Moore’s article is one of the most valuable records of Edgar Degas made by his contemporaries. Among other things, Moore said: "Well, be that as it may, it is certain that today his one wish is to escape the attention of the crowd. He often says his only desire is to have eye-sight to work ten hours a day."

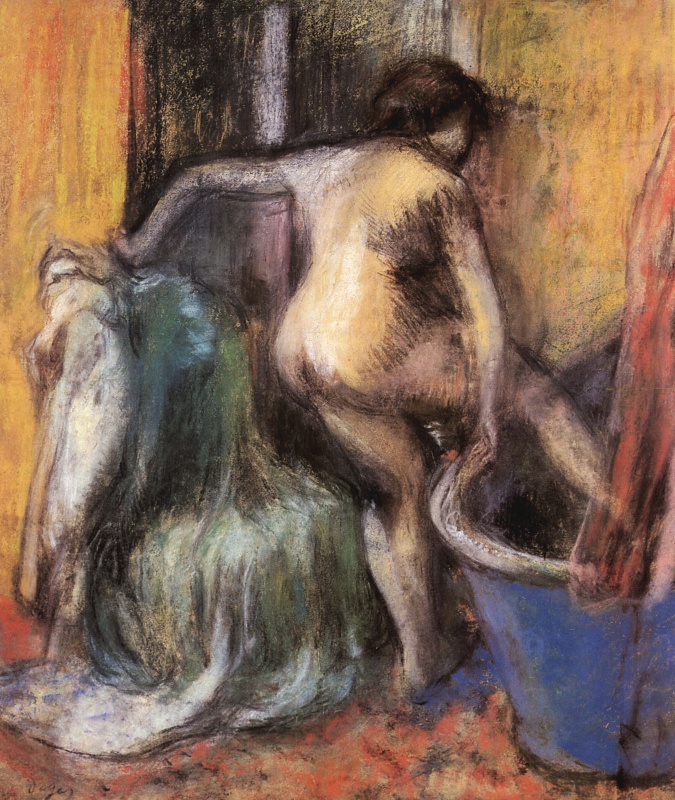

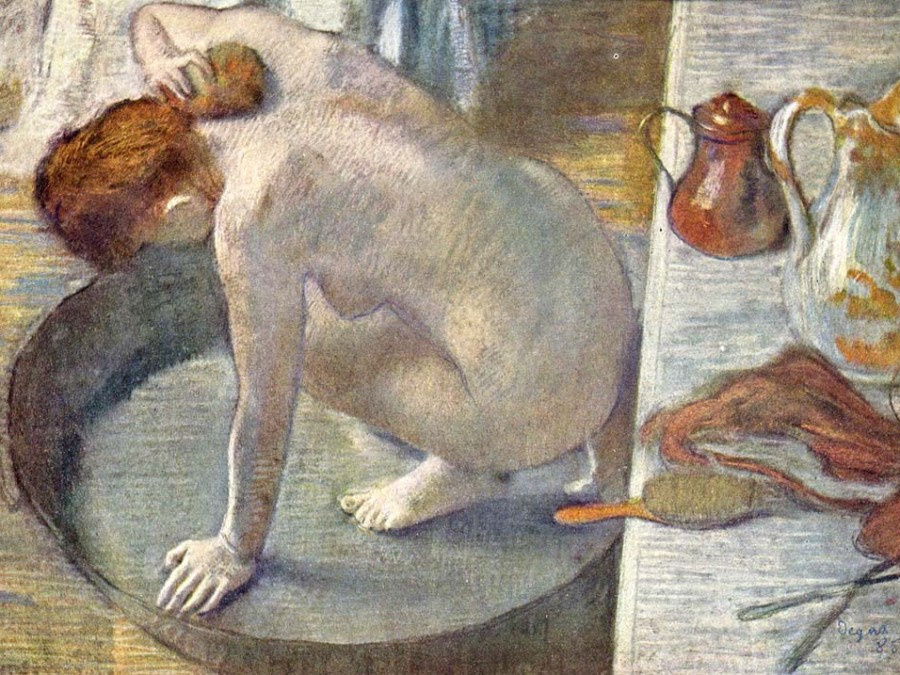

And in 1889 Degas took up poetry: he wrote about 20 sonnets. When the artist Berthe Morisot heard the news at one of the dinners, she smiled: "Are they even poetic? Or is it just a new variation on the theme of bathing?"

When Degas told stories out loud, they resembled plays. He gestured, changed voices, grimaced, joked, made spiteful remarks and used a lot of quotes. Degas’s friends used to say that it was his passionate Neapolitan blood that turned him into an actor. The story about the lady adjusting her dress in the omnibus became a real performance. Degas was telling and demonstrating straight away how she sat down, straightened her dress, pulled up her gloves, looked into her purse, bit her lips, tidied first her hair, and then her veil. Less than a minute passed — and she again felt discontent with her own posture and the state of her dress. And Degas repeated everything again. Women were a separate, sweet, inspiring target of his wit.

But rumours about Degas’s oddities, bachelor principles, and sterile celibacy wander from letters to memoirs, from his sitters' gossip to literary recollections of his friends. "This strange gentleman was combing my hair for four hours," whispers the sitter. "He is not equipped for love," said the other one meaningfully. Gossip is tenacious and readable — even now, when Degas’s bathing women can no longer cause those squeamish, bashful reproaches (after all, we live in the era of art after Lucian Freud!), some journalist or writer will still bring back Degas’s voyeurism, impotence or perverted perception of women.

It seems that Vincent van Gogh understood everything about Degas’s celibacy better and earlier than others: "Degas lives like a little notary and does not love women because he knows that if he … spent a lot of time kissing them he would become mentally ill and inept…"

Once in the opera, Degas met Georges Clemenceau, a famous politician, Jacobin, a merciless "destroyer of ministries." Degas began to share his ideas about political activities with the future Minister of War. He said that if he were a politician, he would lead the most inconspicuous, modest life, place his professional duties above personal ones and give all his strength to the well-being of people and the country. Having heard this story, Paul Valéry asked Degas: "So what did Clemenceau tell you?" "He looked at me with such contempt," Degas replied.

In old age, he would remain lonely, irreconcilable, self-righteous, principled and abandoned by everybody. He believed in the impeccable honesty of the French officers in the notable case of Captain Alfred Dreyfus — and wasn’t going to listen to other opinions. He ceased to communicate with Pissarro (because he was a Jew), Monet and Zola (because they supported the Jew Dreyfus, who defamed the military), and with his closest and oldest friend Ludovic Halévy and his entire family (for the same reason). He didn’t believe even the indubitable proof of Dreyfus’s innocence.

In the last 20 years of his life, Degas was surrounded only by young poets and writers, those of the new generation, worshipping his artistic gift. And yet, Degas met with them quite seldom and reluctantly.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

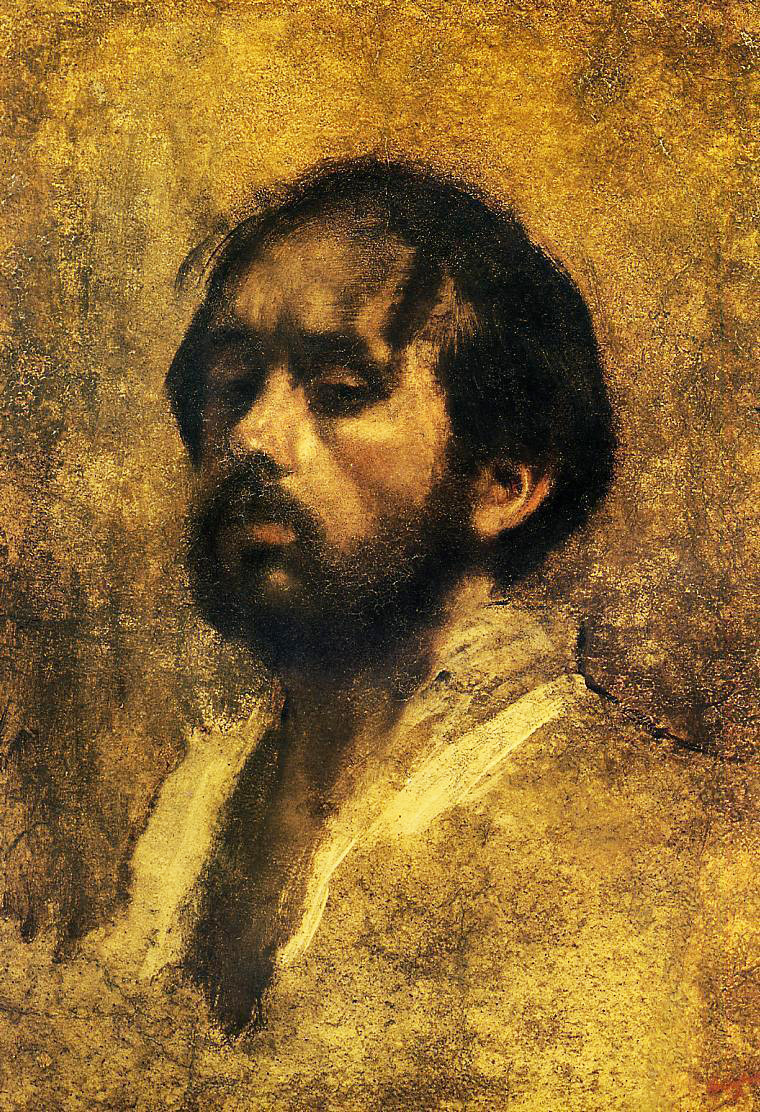

Cover photo: Edgar Degas. Self-portrait. 1895