African adventures: what Delacroix, Renoir, Sargent, Matisse and Klee looked for on the other side of the Mediterranean

If we try to make an ideal life-long tourist route for an artist, based on biographies of the XIX—XX centuries, there will be several mandatory destinations. In order to study painting it is necessary to go to Paris, if you want to gain experience — go to Italy, and when the time comes for some drastic changes — it’s urgent to go to Africa. Why were European artists (and writers, by the way) so eager to go to Africa? What did they find or not find there? And how, for that matter, did it influence their art?

Why Africa?

The simplest and quickest answer to the question of why French artists began to travel to North Africa in the XIX century is: because they could. One more thing: because they already heard something about it.The real interest of the French to the East began with Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign — precisely at the turn of the XVIII and XIX centuries. Because in addition to soldiers and generals, Napoleon took with him several thousand scientists and artists to the African campaign. They had their own tasks: local art, architecture, language, customs, and nature. Already in 1809, France began to issue a huge 23-volume edition of "Description of Egypt" with the materials of these studies, in the Louvre there appeared the first exhibits exported from Africa, and in the suburbs of Cairo — the Institute of Egypt established by the French.

In Europe, the East became a separate discipline of some cool scientific communities, large noisy editorial offices published magazines about the East, and there appeared some individual explorers of the East: linguists, historians and naturalists. Jean-François Champollion, a brilliant 32-year-old linguist, deciphered Rosetta Stone’s hieroglyphics and Egyptian writing in general. Rich adventurers used to go on trips, returning bearded and tanned, bringing from Africa weapons, embroidered outlandish clothes, smoking a hookah and drinking coffee. They were the most welcome guests of the trendy Parisian bohemian salons. They had something to tell. Victor Hugo wrote "Les Orientales", and Gustave Flaubert — "Salammbô".

Eastern people, Eastern wisdom, Eastern colours, Eastern customs, Eastern women, Eastern beauty, along with Eastern ignorance and immorality became the main topics for conversation and fantasy. And North Africa was the closest (one could get there either swimming across the sea or through Spain straight to Tangier) place to find one’s own East, spiritual revelations, erotic adventures, and the most accessible exotic.

Algeria became a French colony in 1830 and Tunisia — by the end of the century. That meant travelling without fear: one could find themselves in a different world, on the other pole, away from civilization, journalists, salons, politics, revolutions, but under the convenient protection of French diplomats, the army and the government.

Algeria became a French colony in 1830 and Tunisia — by the end of the century. That meant travelling without fear: one could find themselves in a different world, on the other pole, away from civilization, journalists, salons, politics, revolutions, but under the convenient protection of French diplomats, the army and the government.

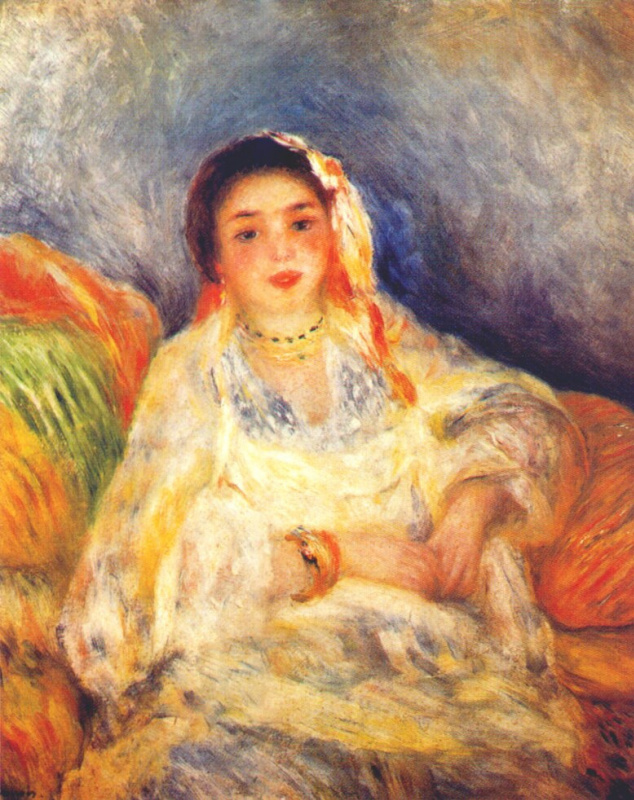

Algerian women

1834, 180×229 cm

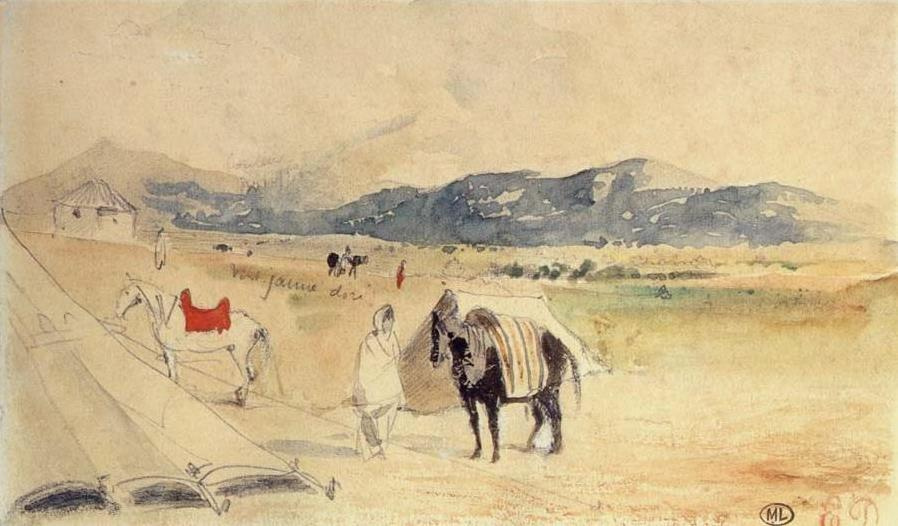

An almost diplomatic voyage of Eugène Delacroix

The Peace Treaty signed between France and Morocco implied rather stable relationships, which still sometimes, once in a few years, required sending an ambassador with regular threats or gifts. In 1833, the French ambassador, Count de Mornay, was chosen to go with a gift to the Sultan, and Eugène Delacroix got permission from the Ministry to join the diplomatic mission. As… a bored artist. By that time he had already painted The Massacre at Chios, The Death of Sardanapalus and Liberty Leading the People — his imagination, infinitely rich and rapid, was fueled by literary plots and the distant tragic events which were written about in the newspapers. But then he need live impressions — he needed Africa."Imagine, my friend, what it is to see lying in the sun, walking in the streets, or mending old shoes, such consular characters, Catos and Brutuses lacking not even that disdainful look the masters of the world must have had. These people have but one blanket in which they walk about, sleep and are buried, and they appear as satisfied with life as Cicero sitting on his curule chair," Delacroix wrote to his friend from Morocco.

Waiting for the meeting with the Sultan took several days — and the artist had time to fill the pages of his road album with sketches of landscapes and urban views, visit bazaars and festivals, and almost die at the hands of local men who found Delacroix painting their wives. The local Moors didn’t not agree to pose for the artist, so he just watched them from afar: on the streets or in the baths.

Delacroix would paint that diplomatic meeting with the Sultan more than a dozen years later, longing in Paris for African solemnity, grandeur, white clothes and white light, which used to bathe everything around.

So, the main mission was completed and Delacroix with Count de Mornay went to Algeria (the then French colony) for a few days. There would be a small event that would affect not only the painting of Delacroix, but also the work of several generations after him. The artist would go to the harem, and after arriving in Paris, based on his Algerian sketches, would create a painting Algerian Women, which would become a textbook of a new, saturated with color and light, painting.

Delacroix would paint that diplomatic meeting with the Sultan more than a dozen years later, longing in Paris for African solemnity, grandeur, white clothes and white light, which used to bathe everything around.

So, the main mission was completed and Delacroix with Count de Mornay went to Algeria (the then French colony) for a few days. There would be a small event that would affect not only the painting of Delacroix, but also the work of several generations after him. The artist would go to the harem, and after arriving in Paris, based on his Algerian sketches, would create a painting Algerian Women, which would become a textbook of a new, saturated with color and light, painting.

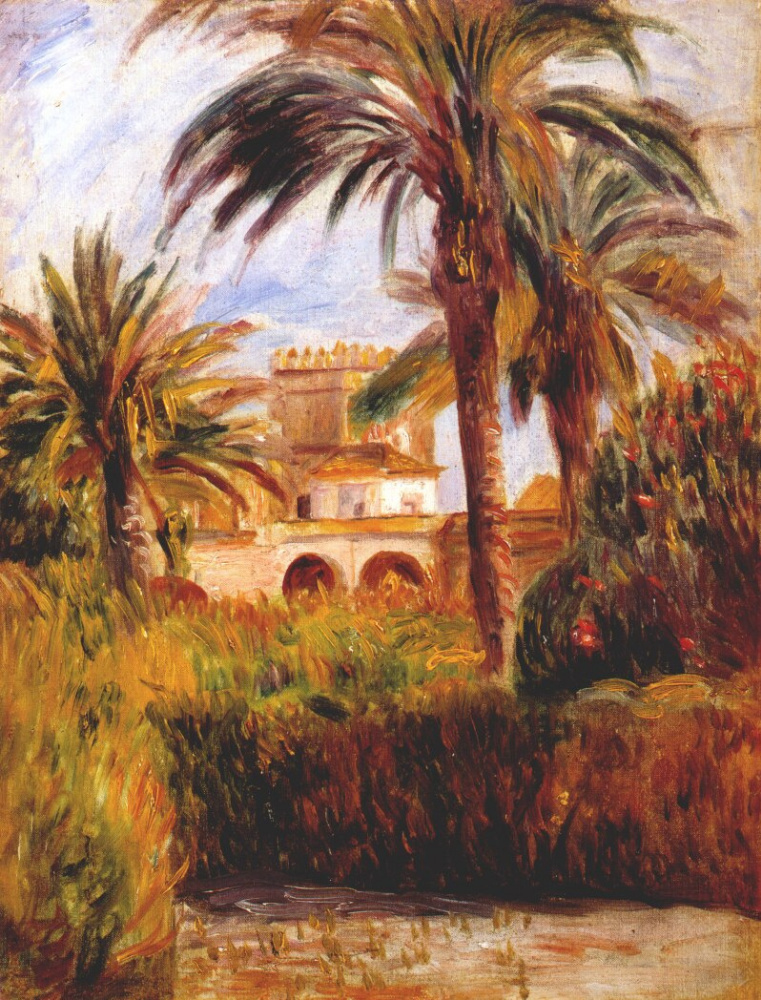

Garden in Algiers

1882

Renoir's Prenuptial Journey

Auguste Renoir went to Algeria 50 years after Delacroix visited it. He had already made a copy of the Algerian Women and several hommages. He felt that Delacroix found the secret of colour only in Africa. And he dreamed of Algeria and his own secret.The 40-Year-Old Renoir had already experienced several exhibitions of the Impressionists and an exhausting struggle for the understanding of the public. The artist was accepted, but only individual enthusiasts were ready to pay for his paintings. He was in love, but something prevented him from making an important decision and casting his lot with young Aline. His art was stuck in an already exhausted, tired pursuit of truth. And the truth, repeated dozens of times, sounded hollower.

He went to Algeria through Italy, lived in cheap hotels and farm houses. Algeria made him dizzy. He almost didn’t paint, and made only few sketches. He just watched: "I discovered the value of white in Algeria. Everything is white: the burnous they wear, the walls, the minarets, the road… And against it, the green of the orange trees and the grey of the fig trees."

But it turned out that 50 years of colonization ousted a living, real life into the mountains. There still lived the descendants of those Catos and Brutuses, whom Delacroix met: they grazed sheep and goats, looking at the sky with an inexplicable grandeur. But down in the city, there appeared offices, trams, workshops, and there came teachers, ready to share civilized knowledge.

Renoir would return to Paris and create more than a dozen paintings — all about dazzling white Algeria. He would start living with Aline Charigot, and would never part with her. If the unhasty, noble Algerians taught Renoir something, it was definitely a desire to live today and not be afraid of tomorrow.

Renoir would return to Paris and create more than a dozen paintings — all about dazzling white Algeria. He would start living with Aline Charigot, and would never part with her. If the unhasty, noble Algerians taught Renoir something, it was definitely a desire to live today and not be afraid of tomorrow.

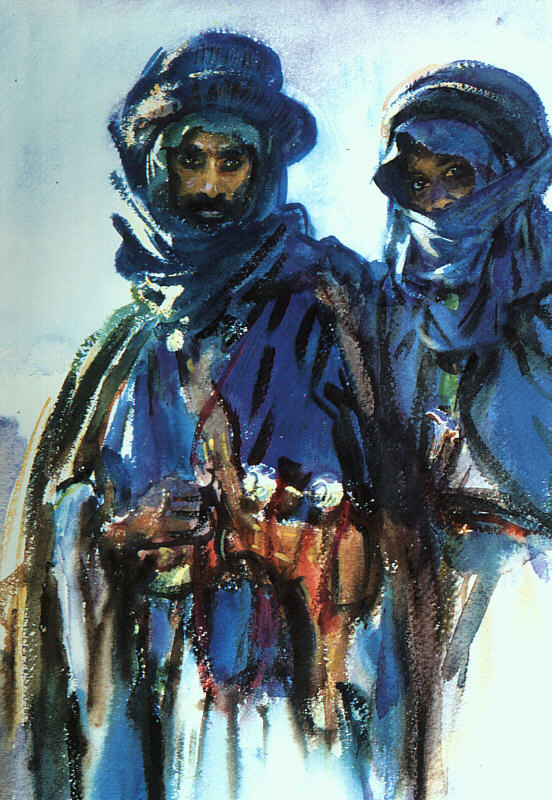

Three Moroccan women in the background of the fortress (Beduine)

1880, 35.2×26 cm

John Singer Sargent Passing Through Africa

Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt are quite expected points on the travel map of John Sargent. If it were possible to calculate the kilometers of his travels around the world and the time spent on the road, he would probably become a record-breaking artist. He was even born a tourist — on a long-term European tour of his parents. And he spent his childhood moving from Italy to France, from Spain to England. His first childhood drawings were travel sketches.These trips fulfilled his passionate, or even innate craving for new impressions, and determined his professional genre predisposition. The fact is that in the Paris workshop, where Sargent took lessons, he was taught that portraits were sold better. He believed his teacher, and then became personally convinced of the fidelity of this instruction, earning well and being really famous. But at the same time he was just a brilliant, masterful landscape painter.

Judging by the dates on African watercolors and canvases, Sargent visited Africa at least three times. In 1891, already being a permanent resident of London, the artist even reached Egypt. Here he found the same thing as in any other unfamiliar city — the opportunity to sit down with a watercolor album on some sun-warmed stone and paint everything surrounding him. People, architecture, trees and rocks. Sargent, who did not take his own watercolour

sketches seriously, was very surprised when the Brooklyn Museum of Art bought all the paintings from his first exhibition of watercolours, and the Boston Museum — from the second one.

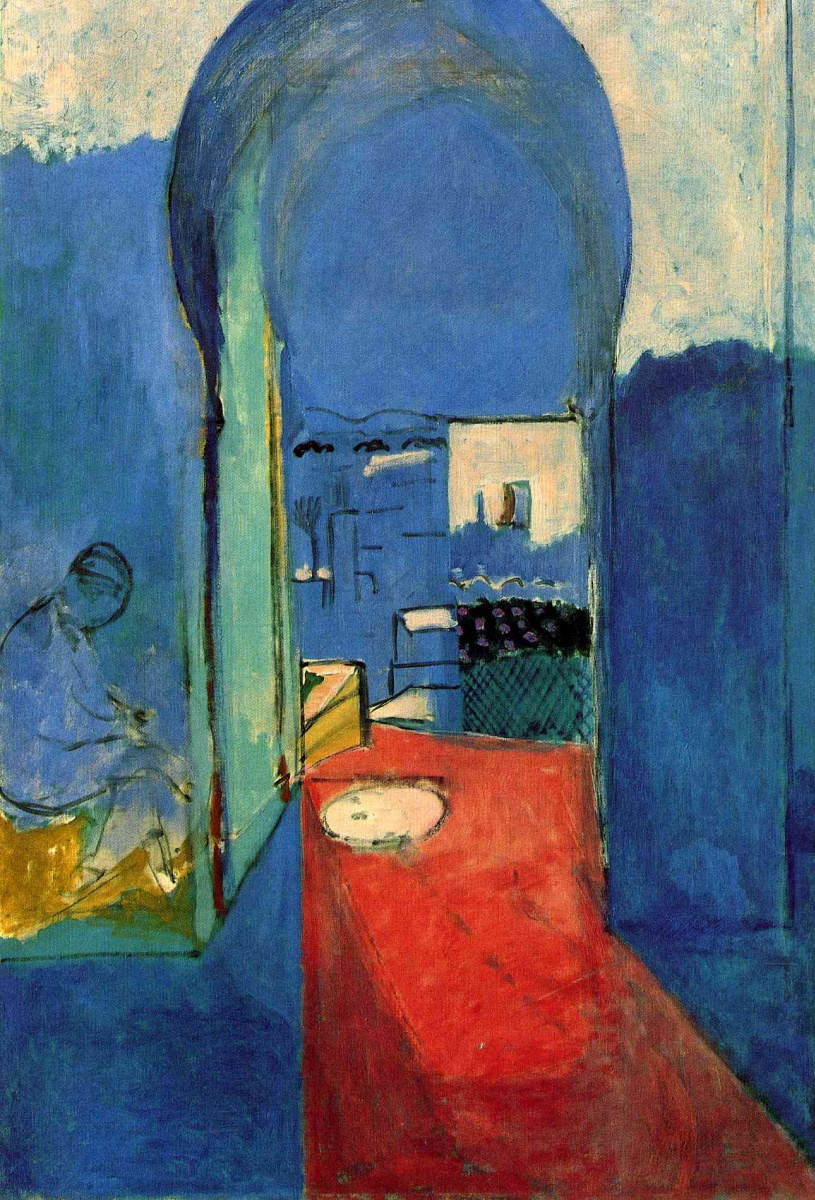

Entrance to the Kasbah

1913, 80×116 cm

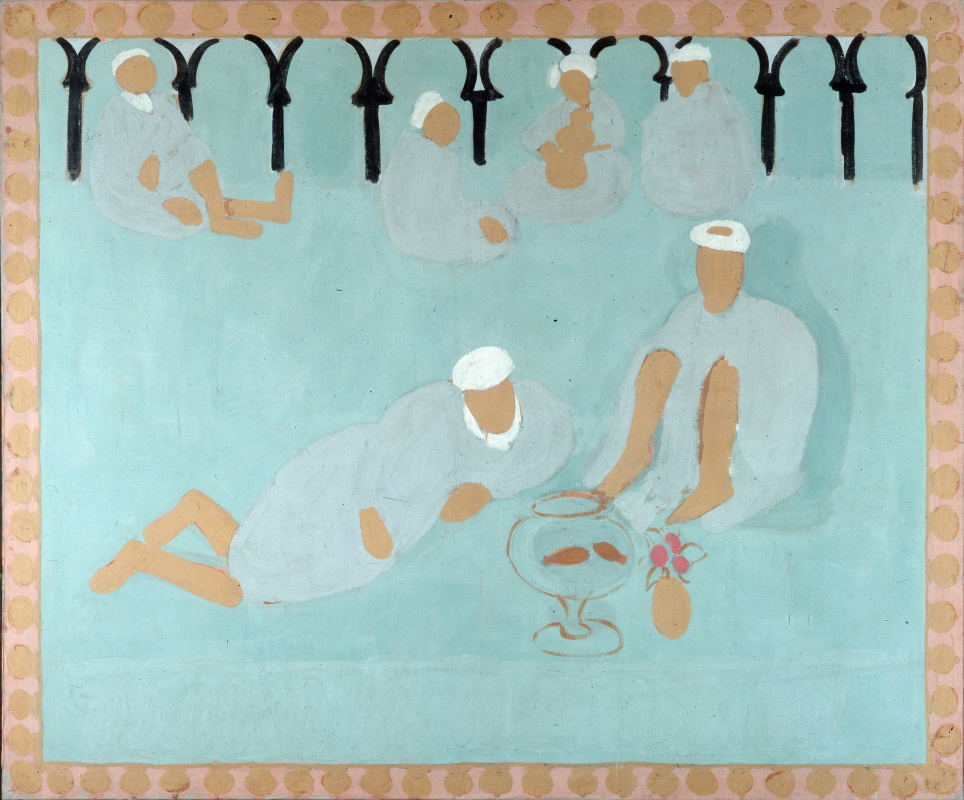

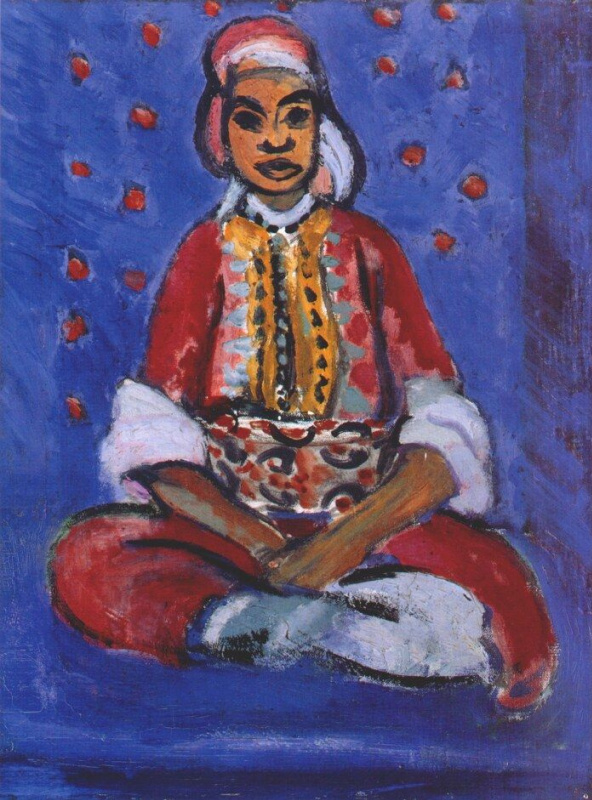

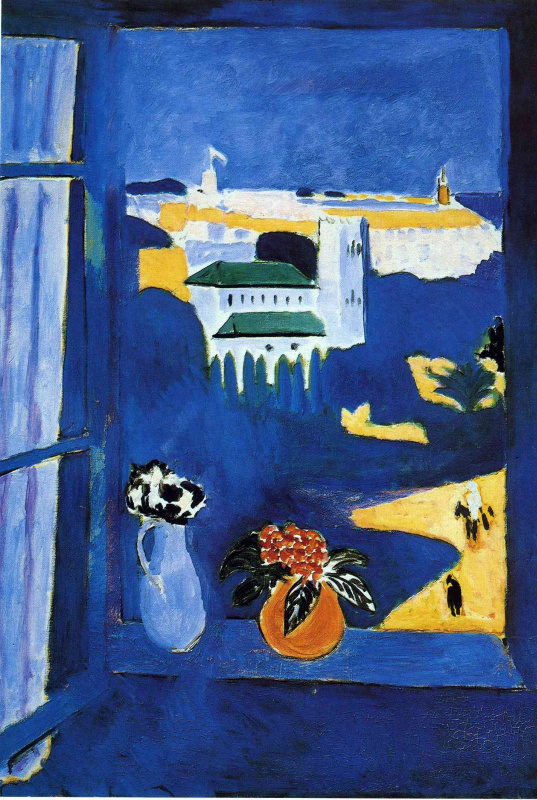

Matisse's Commissioned Trip

When Henri Matisse arrived in Tangier in the winter of 1912, there was already a whole French quarter with hotels, cafés, telegraph, shops, brothels, and local bureaus of European newspapers. Eastern outlandish things could be found only in the market, and the houses of the Moroccans were still inaccessible to the European. In order to work calmly, Matisse had to find a secluded villa, using his connections with local French.The artist arrived in Morocco not because of yearning or the thirst for exotics and adventures — he received a commission connected with Africa. Russian collector Sergei Shchukin commissioned him to paint several pictures with Moroccan motifs and hinted that he would like to see people on them. At the same time, Matisse thought that it would be nice to finally fulfill another long-standing commission from another Russian, Ivan Morozov.

The journey went wrong from the very beginning: Matisse and his wife came to Tangier in the rainy season and spent two weeks looking from the window of the cramped hotel at the unpaved roads that were turning into mud rivers. And only when the rain stopped and the ground was covered with lush vegetation, Matisse felt that he was looking at the same land that Delacroix wrote about almost 100 years ago. Finding models wasn’t an easy task: only with the help of his friends and hotel owners he persuaded a 12-year-old brothel employee Zorah and a hotel groom Amido to pose for him.

In his palette there appeared new colours: colours for a transparent quiet Moroccan night, and for the impenetrable, wild, majestic appearance of a local highlander. In his paintings, a new ornamentality arose: conventional images, patches of pure colour, patterns that flew from the objects to the background. In those places, as Matisse wrote, "his eyesight was restored".

The artist had to leave Tangier in a hurry: the Moroccans raised an uprising against the French troops and French rule. Just a couple of days after his departure, the local Arabs walked through Tangier’s European quarter with the heads of the French on their peaks. Of course, the uprising would be suppressed — and Matisse would return to Africa.

The artist had to leave Tangier in a hurry: the Moroccans raised an uprising against the French troops and French rule. Just a couple of days after his departure, the local Arabs walked through Tangier’s European quarter with the heads of the French on their peaks. Of course, the uprising would be suppressed — and Matisse would return to Africa.

Mosque

1914, 23×22 cm

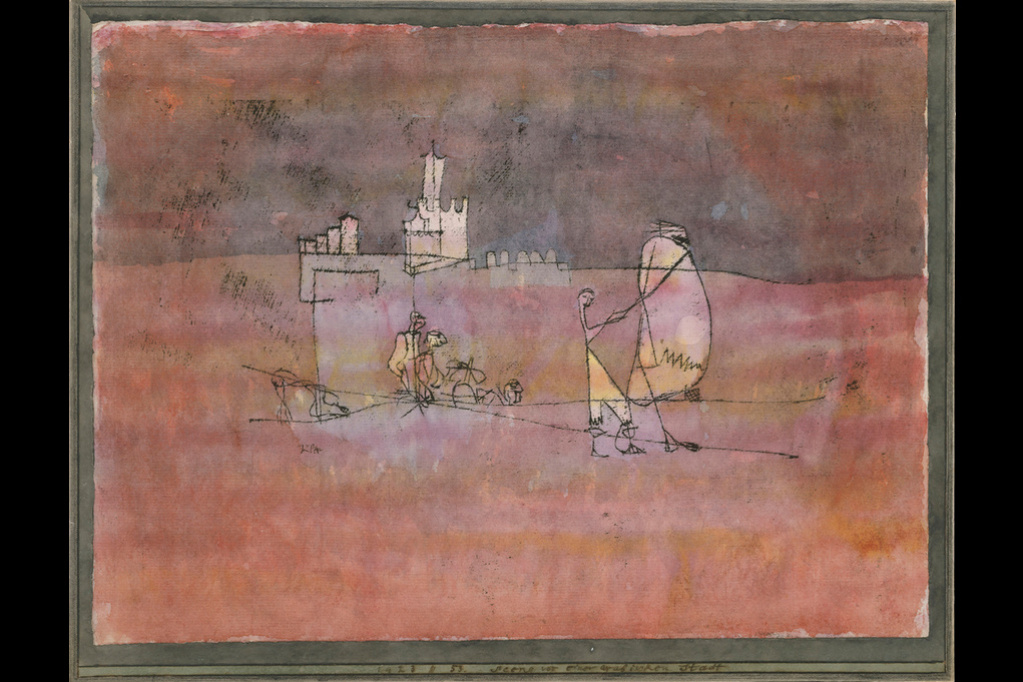

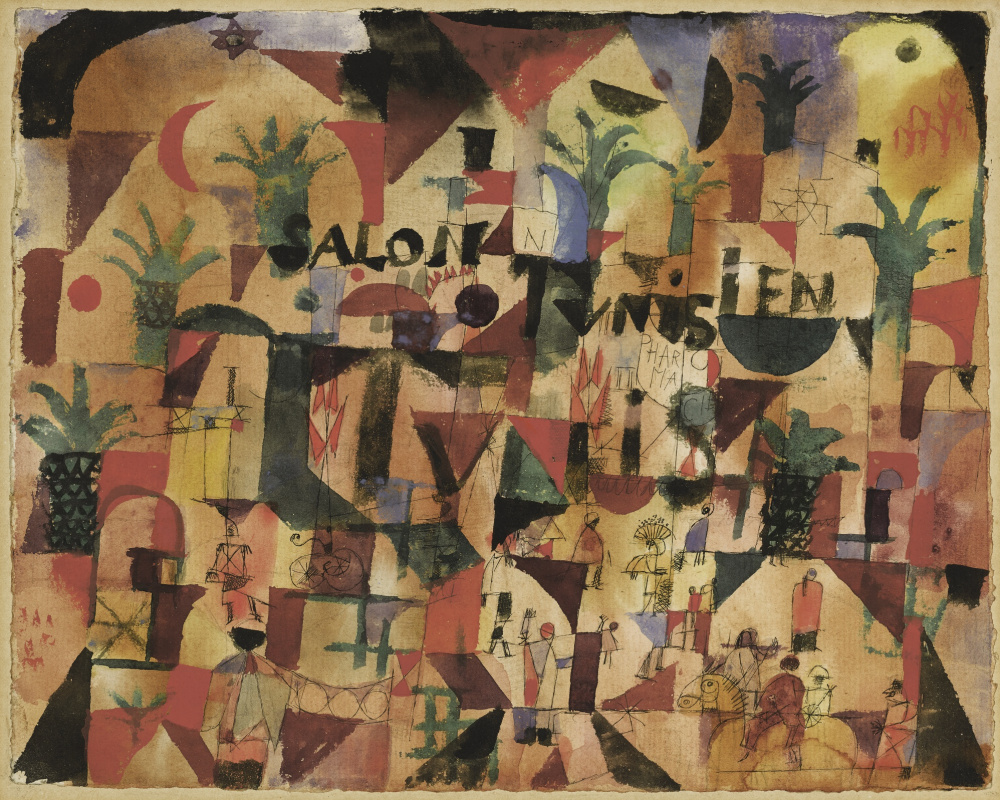

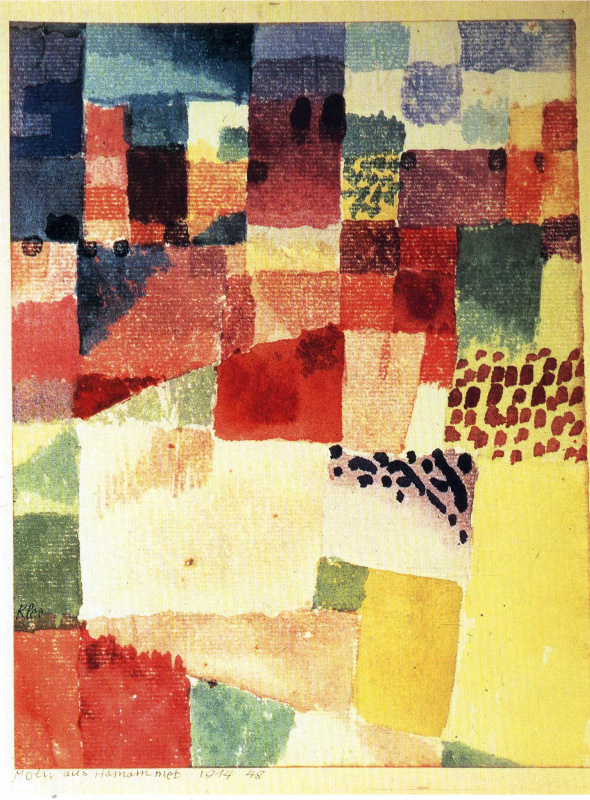

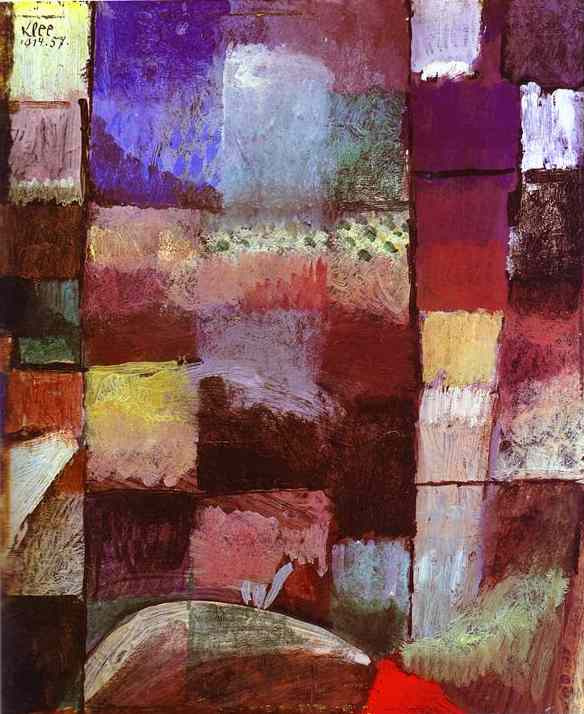

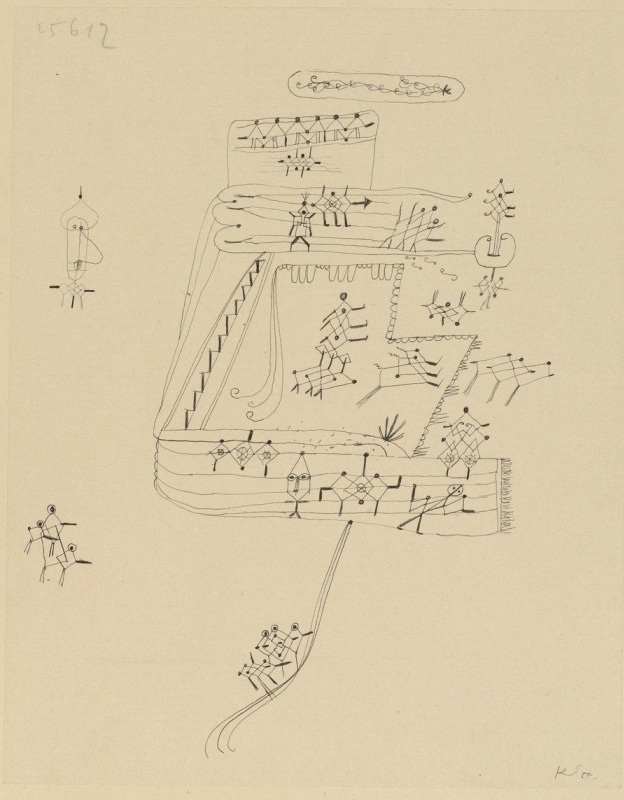

Paul Klee's African Initiation

Swiss by origin, Paul Klee went to Tunisia from Germany, where he lived at that time. He was 35 years old, interested in cubism, fond of graphics, and a member of the artistic group "The Blue Rider." He went to Africa together with his two friends — artists August Macke and Louis Moilliet. After a few decades, art historians would call this African journey the beginning of modernism."Colour has claimed me. I need no longer run after it. I and colour are one. I am a painter," wrote Klee in his diary, standing at the gates of the Islamic quarter of the city of Kairouan. And he wasn’t exaggerating. Africa made sounds, and musician Klee listened to them: to the sound of voices, the cries of animals, the melodies of local songs. Africa smelled, and Klee inhaled it: the smell of spices, fabrics, hot stones, sea, and city. Africa shone in the sun, and Klee looked at it: at the patterned windows, doors, Hammamet’s domes, cacti, reeds, and lush gardens. There he understood how to paint objects without depicting their form in precise detail. And he understood that he had to paint smells, colours and sounds — the feelings experienced in Africa, but not landscapes and local residents.

Coming back from this two-week trip, the artist brought with him 35 watercolours, 13 paintings and a new understanding of painting. All his life he would return to the African impressions and create more than 20 paintings connected with Tunisia. These memories didn’t fade — they became part of his artistic inspiration, an endless fuel for new discoveries. Figures and objects turned into Klee’s paintings into a new African secret, a new hieroglyphic writing, new signs, a new Rosetta Stone of painting that no one would ever decipher. Even a brilliant linguist.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Cover illustration: Eugène Delacroix. Moroccans Outside the Walls of Tangier. 1834