Imagine that you enter the museum hall and see that its whole floor is covered with a layer of sunflower seeds. It brings the mood of a surreal dream even before you are told that the seeds are actually an installation, a work of art. "That's ridiculous," you might think. "How can it be art?" What if they tell you that each of the seeds is made of porcelain and painted by hand? "That's impressive. But what’s the point?" And it turns out that while in the West connoisseurs spend tons of money on exquisite porcelain vases and tea sets, Chinese craftsmen work in hellish conditions, making next to nothing while their lives cost even less. And then, the crunch of porcelain seeds under your feet makes your whole body shiver. That’s the way Ai Weiwei works.

When Ai Weiwei’s name became famous on the international art scene, there appeared a joke that the phrase "Made in China" would never be perceived as before. The super power of the Chinese conceptual artist lies in the ability to look at ordinary things from unexpected angle and help others see what he sees. Ideas brought by Ai are not particularly complicated. He talks about the value of human life, combating injustice, humanitarian crises and political persecutions. But the form he casts these ideas into, materials he uses and the new ways of communicating with the viewer make him one of the most impressive figures in contemporary art.

But what made him who he is?

Ai Weiwei’s childhood and youth were far from being easy and happy. He was about a year old when his father, the famous poet Ai Qing, fell into disgrace with the Chinese authorities. Ai Qing and his family lived in exile for almost twenty years, in small villages near the North Korean border and in the province of Xinjiang, where his father was forced to carry out hard labor, including cleaning communal toilets. The family had been able to keep only one book, a large encyclopedia — Ai’s only source of information and education. In order to survive as a child, Ai learned many of the practical skills that he would later apply to his art — such as making furniture and bricks.Ai Qing and his family were allowed to return from exile after Chairman Mao’s death in 1976. Ai almost immediately enrolled in the Beijing Film Academy to study animation and soon became part of a subversive political group of young artists, also taking part in a number of pro-democracy marches and rallies. Five years later, Ai Weiwei moved to the US, where he began his career, but in 1993 the artist had to return to his homeland because of his father’s illness. After Ai Qing’s death, the artist spent several years making furniture and building his own house and studio.

The year 1999 was a turning point in Ai’s life and career. He was chosen to represent China at the Venice Biennale. Having received international recognition, the artist became bold enough to put into life increasingly audacious projects. One of the first such projects was the provocative exhibition of young Chinese conceptualists — an open protest against the unspoken rules that for many years controlled art in the country. In a nutshell, the guidelines were that Chinese art should be representational, respectful, and celebrate the lives of everyday people thriving under Communism in a manner consistent with Western Realism — but mostly known internationally as Soviet Socialist Realism

. The exhibition, co-curated by Ai, became a direct message to the Chinese authorities, explicitly expressed in its title — "F**k off".

Even then, the government considered a rebellious artist to be a threat, since he had clout in the global art community and unveiled the problems that used to be kept secret. But it was after the Sichuan earthquake of 2008 when they got really tough on him. Back then, thousands of schoolchildren died due to the shoddy construction of school buildings in the area, while government officials didn’t release the number of victims to smother up a scandal. Ai started an independent investigation, bringing the facts and evidence to light. But police beat him so badly that he was hospitalized and had to give up further attempts to get at the truth.

And yet, the authorities failed to break Weiwei’s rebellious spirit. And each of their vicious insults was responded to with a new scandalous artistic statement. Let us recall some of Weiwei’s projects in which he entrenched upon the sacred, turned the edible into the inedible and openly talked about political repression.

And yet, the authorities failed to break Weiwei’s rebellious spirit. And each of their vicious insults was responded to with a new scandalous artistic statement. Let us recall some of Weiwei’s projects in which he entrenched upon the sacred, turned the edible into the inedible and openly talked about political repression.

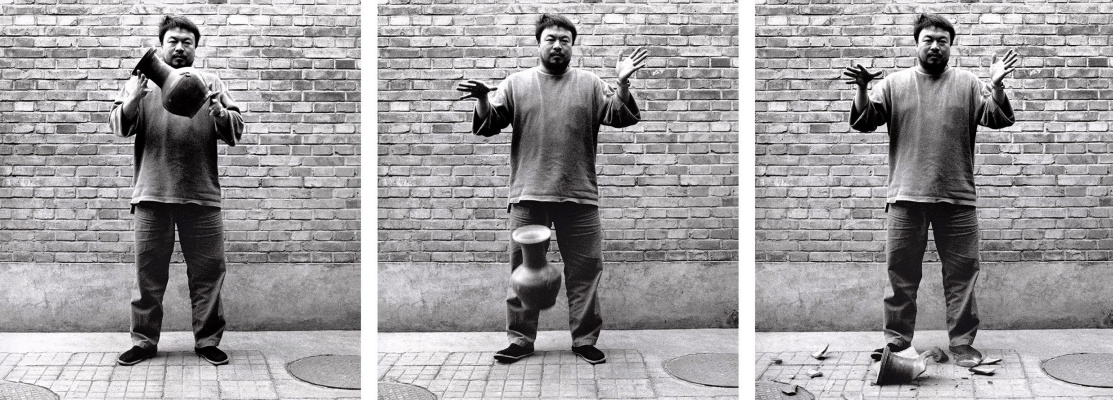

Dropping a Han dynasty urn

1995, 148×121 cm

It is difficult to attribute this shocking gesture to a certain kind of art. It was basically a performance, but without viewers — the one that can be seen only in photos. Ai Weiwei "simply" dropped and smashed a ceremonial urn outside his mother’s home in Beijing and had the process photographed. Not only did the 2000-year old artifact have considerable value (the artist paid the equivalent of several thousand US dollars for it), but symbolic and cultural worth. Antique dealers were outraged, calling Ai’s work an act of desecration. He countered by saying: "Chairman Mao used to tell us that we can only build a new world if we destroy the old one." It was a provocative act of cultural destruction in reference to the erasure of cultural memory in Communist China, an anti-elite society that carefully monitored access to information, especially about its dynastic history. After that, Ai "spoiled" a lot of valuable vessels, but later he only painted them.

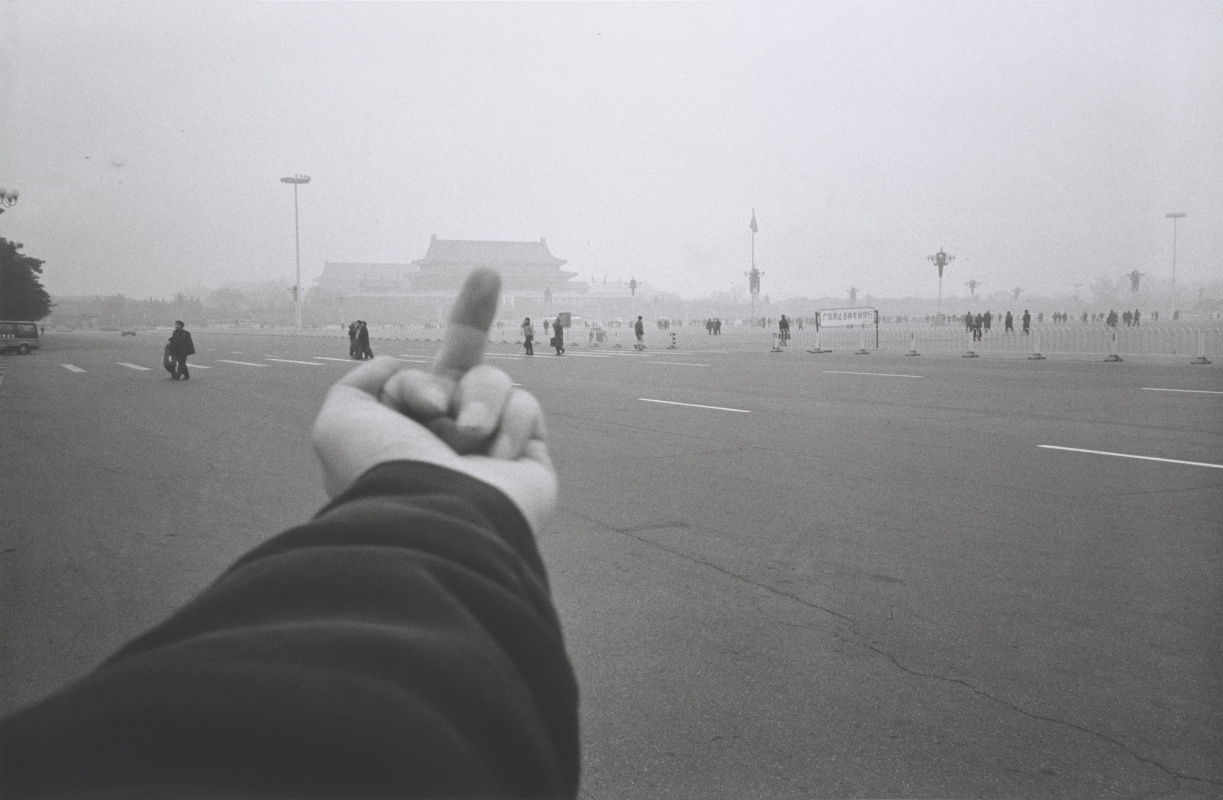

Also known as the "Gate of Heavenly Peace", and formerly the front entrance to the Forbidden City, Tiananmen Square Gate was also the site of the brutal massacre in 1989 in which state soldiers shot peaceful protesters. The Beijiing government still refuses to discuss it, and censors all footage of the event.

The central rule of traditional perspective is that objects closer to the eye must appear larger. In Ai’s photo, the closest object is his finger raised in an offensive gesture and expressing the artist’s disdain for the symbol of state power. It was by no means limited to China: Study of Perspective Tiananmen Square was the first photo of a series capturing his middle finger in front of The Eiffel Tower, The Reichstag and the White House.

The central rule of traditional perspective is that objects closer to the eye must appear larger. In Ai’s photo, the closest object is his finger raised in an offensive gesture and expressing the artist’s disdain for the symbol of state power. It was by no means limited to China: Study of Perspective Tiananmen Square was the first photo of a series capturing his middle finger in front of The Eiffel Tower, The Reichstag and the White House.

There was another layer of visual symbolism

in Ai’s photo which lies in its resemblance to a man photographed in 1989 facing alone a line of tanks. Here the artist’s offensive gesture is a provocative stand in for a figure strictly banned in the Chinese media.

Ton of tea

2008, 100×100×100 cm

It’s quite easy to guess that Ai Weiwei is a connoisseur of contemporary art. Having returned from the US to China in the mid-1990s, he produced three books on interviews with some of his favorite Western artists, including Marcel Duchamp, Andy Warhol, and Jeff Koons. Donald Judd and Robert Morris were also among the artists Ai admired. But it wouldn’t be Ai if he decided to use traditional materials like stone, glass or metal for his minimalist sculpture. This work compresses a ton of traditional pu’er tea leaves (one smells their pungent odor from afar) into the space of one cubic meter.

In the West, drinking tea (especially from Chinese porcelain) has historically been a status symbol. And pu’er is still one of the most expensive varieties of tea. In contrast, in China tea is the everyday drink. And much of it is produced in compressed cubes, so Ai’s sculpture is also a "monument" to an everyday domestic item.

In the West, drinking tea (especially from Chinese porcelain) has historically been a status symbol. And pu’er is still one of the most expensive varieties of tea. In contrast, in China tea is the everyday drink. And much of it is produced in compressed cubes, so Ai’s sculpture is also a "monument" to an everyday domestic item.

Sunflower seeds

2010

In 2010 Ai filled the enormous Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern with exactly 100,000,000 porcelain sunflower seeds, each made by a craftsman from the Chinese city of Jingdezhen, the "Porcelain Capital", where ceramics has been produced for 1700 years. Hundreds of individuals had therefore been hired to produce by hand what appeared to have grown from nature.

The meaning of this work evokes complex associations, connected to Chinese history and culture. Like Ton of Tea, it is made from a substance made for export that has long sustained the Chinese economy. Ai also addresses the issue of contemporary mass-manufacturing practices in China. Much is still made by hand in an economy where machines are expensive and labor (and human life in general) is cheap.

Moreover, the sunflower is an important Chinese communist symbol. Chairman Mao compared himself to the sun and his people to sunflowers. In Beijing, sunflower seeds are sold by urban street vendors. For Ai, a Beijing native, they evoked happy memories of wandering the city with friends. By 2010, however, he was essentially a prisoner in his own city. In this light, his seeds, cast on the ground, evoke an oppressed, downtrodden society, far from the ideal that Mao described. Seeds that will never germinate.

The meaning of this work evokes complex associations, connected to Chinese history and culture. Like Ton of Tea, it is made from a substance made for export that has long sustained the Chinese economy. Ai also addresses the issue of contemporary mass-manufacturing practices in China. Much is still made by hand in an economy where machines are expensive and labor (and human life in general) is cheap.

Moreover, the sunflower is an important Chinese communist symbol. Chairman Mao compared himself to the sun and his people to sunflowers. In Beijing, sunflower seeds are sold by urban street vendors. For Ai, a Beijing native, they evoked happy memories of wandering the city with friends. By 2010, however, he was essentially a prisoner in his own city. In this light, his seeds, cast on the ground, evoke an oppressed, downtrodden society, far from the ideal that Mao described. Seeds that will never germinate.

Surveillance camera

2010, 39.2×39.8×19 cm

In 2010, the Chinese authorities arranged for the artist total surveillance. The Beijing police installed security cameras in his home and studio. Those cameras tracked him from room to room, and even outside. They also closely monitored his posts on Twitter and Instagram. Ai said: "In China, I am constantly under surveillance. Even my slightest, most innocuous move can — and often is — censored by Chinese authorities." The artist, in turn, tracked the surveillance cameras, vans, and plain-clothes police officers that monitored his gates.

Surveillance Camera, an austere and quite beautiful marble sculpture, reminds us that the artist is watching those who watch him. Like tea or porcelain, his choice of medium has significance. A surveillance camera set in stone reminds us of the omnipresence of this feature in the artist’s life. Set on a plinth at eye level, the resemblance of the shape to a head and shoulders is a visual twist characteristic of Ai’s broader sense of humor.

In 2012, he set up "Weiwei Cam", broadcasting a live feed and invited his followers to view him at work and going about his business, mimicking the intrusion of Chinese officials into his private life, but here the viewers watched him at his invitation. Authorities quickly shut it down (within two days), but it remains a testament to Ai’s persistent wit, and unwavering commitment to holding his government publicly responsible for its intrusions into the lives of its citizens.

Surveillance Camera, an austere and quite beautiful marble sculpture, reminds us that the artist is watching those who watch him. Like tea or porcelain, his choice of medium has significance. A surveillance camera set in stone reminds us of the omnipresence of this feature in the artist’s life. Set on a plinth at eye level, the resemblance of the shape to a head and shoulders is a visual twist characteristic of Ai’s broader sense of humor.

In 2012, he set up "Weiwei Cam", broadcasting a live feed and invited his followers to view him at work and going about his business, mimicking the intrusion of Chinese officials into his private life, but here the viewers watched him at his invitation. Authorities quickly shut it down (within two days), but it remains a testament to Ai’s persistent wit, and unwavering commitment to holding his government publicly responsible for its intrusions into the lives of its citizens.

River crabs

2011

At first glance, there is nothing extraordinary about this work. It’s just a pile of beautiful individually-crafted porcelain crabs, isn’t it? But do you really think that Ai Weiwei is able to create something that is not full of subtexts and hidden meanings? The installation is called He Xei, Chinese for "river crab". Yet, in a complex system of homophones designed to evade government detection, it also means "censorship". Thirdly, it sounds like the term for "harmonious", and a well-known Chinese Communist Party slogan prizes the "realization of a harmonious society" - this is often the reason given for limiting access to information.

If you think about it, it becomes obvious that this society of crabs/censorship is far from harmonious. Cast in black and red (the colors of the Chinese Communist Party) these hard-shelled creatures trample each other. The few that escape the pile seem especially vulnerable. In 2014 a visitor accidentally stepped on one and crushed it, an unintended metaphor for the consequences of resistance.

Like his sunflower seeds, 3000 porcelain crabs were crafted and painted by hand. There is also an autobiographical dimension to the work. In 2010 Ai was informed that his newly built studio would be torn down (authorities claimed he had not had the right permit). In response, Ai publicly announced he was holding a feast in celebration of the destruction of his studio. He invited 800 people and ordered 10,000 crabs. Officials, who understood but who did not appreciate the gesture, placed the artist under house arrest. While unable to attend the event, he was still able to broadcast it internationally and in near-real time. After Ai Weiwei’s studio had been destroyed, the artist used its concrete and brick rubble to create the Souvenir from Shanghai installation and set it in a rosewood bed frame .

If you think about it, it becomes obvious that this society of crabs/censorship is far from harmonious. Cast in black and red (the colors of the Chinese Communist Party) these hard-shelled creatures trample each other. The few that escape the pile seem especially vulnerable. In 2014 a visitor accidentally stepped on one and crushed it, an unintended metaphor for the consequences of resistance.

Like his sunflower seeds, 3000 porcelain crabs were crafted and painted by hand. There is also an autobiographical dimension to the work. In 2010 Ai was informed that his newly built studio would be torn down (authorities claimed he had not had the right permit). In response, Ai publicly announced he was holding a feast in celebration of the destruction of his studio. He invited 800 people and ordered 10,000 crabs. Officials, who understood but who did not appreciate the gesture, placed the artist under house arrest. While unable to attend the event, he was still able to broadcast it internationally and in near-real time. After Ai Weiwei’s studio had been destroyed, the artist used its concrete and brick rubble to create the Souvenir from Shanghai installation and set it in a rosewood bed frame .

In 2011 Ai Weiwei was arrested at Beijing International Airport. He was detained 81 days without formal charges. At the 2013 Venice Biennale, he presented the S.A.C.R.E.D. project, providing a realistic representation of life in prison. Ai created six dioramas depicting him inside a prison cell: we see Ai being interrogated, having a shower, eating, sleeping, and relieving himself, all of it while the two guards look on. This method of treating prisoners was designed to break the spirit of a person locked in four walls. But it only impelled Ai Weiwei to let the world know about the state of things in China. The following year, at an exhibition in Berlin, he showcased life-size replicas of his cell. One could go inside the cell, examine its highly modest adornments, touch the walls covered with soft foam, stand under the lamps working round the clock, and even look into the toilet.

Trail

2014

Continuing on the topic of confinement, Ai’s next project was implemented in a real, but no longer functioning prison — Alcatraz. And it was also devoted to combating human rights violations and restriction of freedom of expression.

The Trace installation consists of portraits of 176 people who have been jailed or exiled for their beliefs or political affiliations (i.e. Nelson Mandela, Edward Snowden and Nobel prize-winning Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo). Most of these people, whom Ai called "heroes of our time", were still in prison at the time of the installation. What is striking is that the artist himself was unable to attend the exhibition, where Trace was shown, since the Chinese authorities withheld his passport.

The effect produced by the number of characters featured in the installation is enhanced by the complexity of the work done: each portrait was crafted by hand, using Lego bricks. Some parts were created in the artist’s studio, others — directly in San Francisco, by over 80 volunteers managed by the artist.

Ai planned to make another Lego project the following year and made a bulk order for the toy bricks. But the Danish company refused his request saying that they did not endorse the use of their products in conjunction with works that had a political agenda. Ai then took to social media, inviting his supporters all over the world to send him Lego pieces.

The Trace installation consists of portraits of 176 people who have been jailed or exiled for their beliefs or political affiliations (i.e. Nelson Mandela, Edward Snowden and Nobel prize-winning Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo). Most of these people, whom Ai called "heroes of our time", were still in prison at the time of the installation. What is striking is that the artist himself was unable to attend the exhibition, where Trace was shown, since the Chinese authorities withheld his passport.

The effect produced by the number of characters featured in the installation is enhanced by the complexity of the work done: each portrait was crafted by hand, using Lego bricks. Some parts were created in the artist’s studio, others — directly in San Francisco, by over 80 volunteers managed by the artist.

Ai planned to make another Lego project the following year and made a bulk order for the toy bricks. But the Danish company refused his request saying that they did not endorse the use of their products in conjunction with works that had a political agenda. Ai then took to social media, inviting his supporters all over the world to send him Lego pieces.

Current work

In recent years, Ai both as an artist and political activist, raises awareness of the humanitarian crises and catastrophes. Most of his recent projects focus on refugees. Sometimes they are large-scale works like his installation of life jackets at Vienna’s Belvedere Palace or a giant boat carrying about 300 oversized human figures at Prague’s National Gallery. But sometimes these are the simplest actions that many are capable of. For instance, when a Syrian refugee in a Greek camp mentioned missing her piano, he had one brought to her and videotaped her performance. Ai said: "The refugee crisis isn’t about refugees. It’s about us."Ai’s impact on the West is arguably greater than it is in China, where he remains a controversial figure. He is an inspirational figure for many people both in and outside the art world. And constantly reminds us of the power of visual art to move us as individuals, and sometimes entire nations, to action.

Ai Weiwei at the Law of the Journey exhibition in Prague.

Arthive on Instagram

Cover illustration: Ai Weiwei with his Sunflower Seeds at Tate Modern.

Author: Yevheniia Sidelnikova.

Cover illustration: Ai Weiwei with his Sunflower Seeds at Tate Modern.

Author: Yevheniia Sidelnikova.