1. Da Vinci: as if handless

This is a chest-high portrait: we can’t see the hands of Ginevra de' Benci, a Florentine beauty and poetess. But her hands are among the most famous ones in the history of art; they even had an effect on other artists.Lorenzo di Credi quite accurately reproduced Leonardo’s work — even painted the juniper in the background, but mirrored the composition.

It’s more complicated when it comes to a sculptural portrait by Verrocchio: the exact date of its creation remains unknown. Verrocchio was Leonardo’s teacher. Perhaps, da Vinci borrowed the idea of hands from his mentor. But the reverse is also possible: the student had already surpassed his teacher by that time — and it could be Verrocchio who was inspired by Ginevra’s hands from Leonardo da Vinci’s painting (at the time of creating Ginevra’s portrait, the girl was about 17 years old, and the artist — about 23).

In his Treatise on Painting, da Vinci wrote a lot about how to depict hands. In particular, he instructed his colleagues: "Represent your figures in such action as may be fitted to express what purpose is in the mind of each; otherwise your art will not be admirable." He himself followed that rule: hands in his works always attract attention (1, 2, 3, 4).

Those were not only the artist’s own artistic principles that would not let him ignore the hands of the girl portrayed. The thing is that those were remarkable hands: at least two poets who wrote poems dedicated to Ginevra, berhymed the beauty of her hands and fingers.

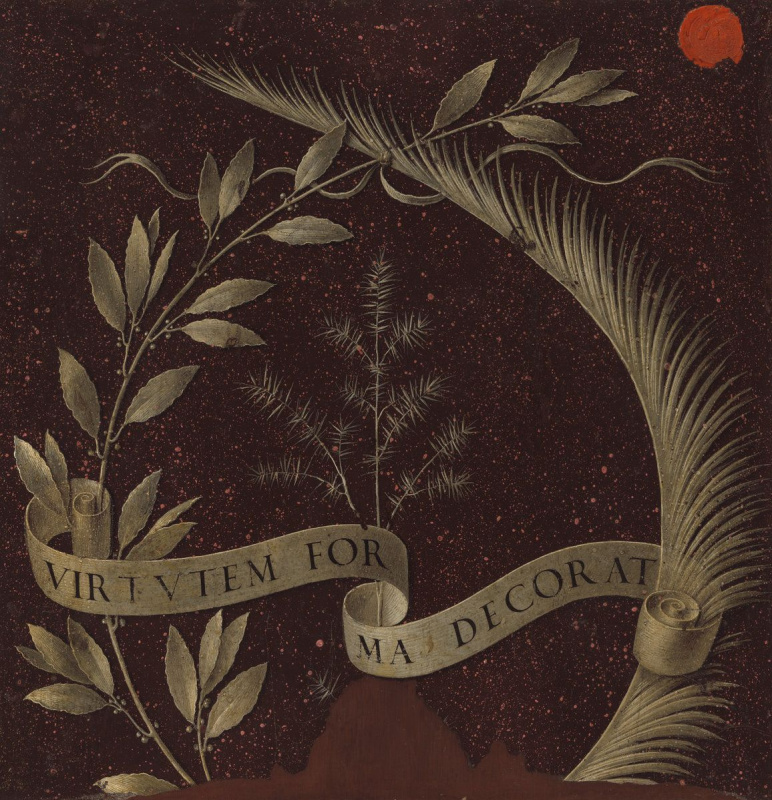

Another proof that the bottom of the painting (9−10 centimetres) was cut off, can be found when looking at the reverse side of the portrait of Ginevra de' Benci.

The reverse is decorated with a juniper sprig encircled by a wreath of laurel and palm and is memorialized by the phrase "Beauty adorns virtue". It seems that the lower part of the wreath was cut off.

But we can only guess why the bottom of the painting with Ginerva’s hands had to be removed. Perhaps, the fragment was damaged by dampness, fire or rodents.

By the way, it is possible that Leonardo’s La Gioconda was also cut down: apparently, the painting was originally wider and had side columns (they can be seen in one of the earliest copies).

2. Bosch: when fools and gluttons were together

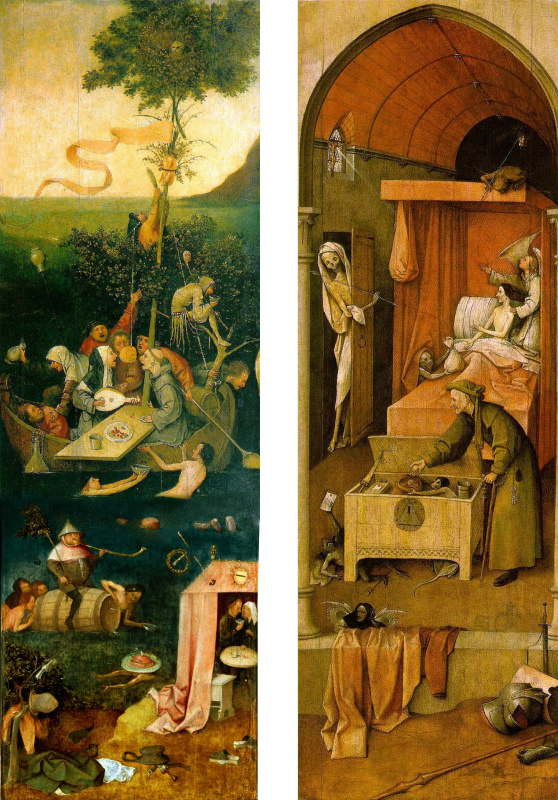

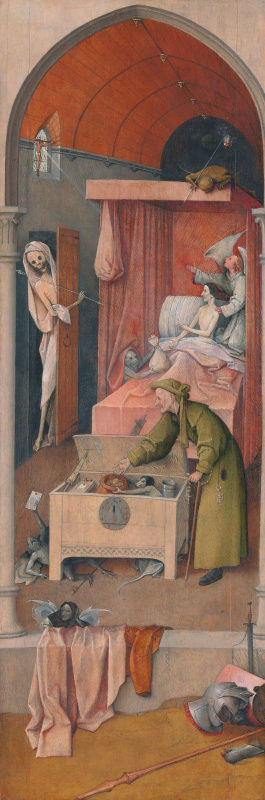

In 2016, a great exhibition, marking the 500th anniversary of the artist’s year of death was held in 's-Hertogenbosch, the city where Hieronymus Bosch was born and lived. It reunited four fragments of a lost triptych, which was probably dedicated to deadly sins.The Wayfarer was brought from Rotterdam — this famous image is believed to have been the outside shutters of the triptych. As for the internal parts — unfortunately, the central one hasn’t been preserved. But the side panels survived: one of them is Death and the Miser (now in Washington), while the second one was also cut and known to us today as two separate paintings by Bosch — The Ship of Fools (the Louvre) and Allegory of Gluttony and Lust (the Yale University Art Gallery).

It turns out that one of Bosch’s most famous paintings, The Ship of Fools, is just a small fragment of a triptych.

In general, this is not a unique case when parts of multi-panel paintings get separated. Then their "reunion" at exhibitions looks like a happy plot twist in melodramas: recently, the parts of The Melun Diptych have been reunited.

It is not uncommon when only small parts remain from the whole painting and continue to live as independent works. Such is Head of an Angel by Raphael: it is a detail of a large altarpiece The Coronation of Saint Nicholas of Tolentino, Treading on a Devil — the angels just stood next to him (three more fragments remained from this altar — the second angel, God the Father, and the Blessed Virgin Mary).

3. Carpaccio: a flower explains a lot

Carpaccio’s painting of two elegantly dressed Venetian ladies has always been considered an undisputed masterpiece and has always been surrounded by mysteries and questions: who are these ladies — courtesans or respectable women? Who are they waiting for — clients or husbands? And what was depicted in the lost parts of the painting?The left part hasn’t been found. But the upper one was found and clarified a lot.

The Venetian ladies still sit looking into the mysterious distance (or deep inside themselves?) in the Correr Museum in Venice. And the Getty Museum in Los Angeles houses another mysterious painting Hunting on the Lagoon: in the foreground, against the background of the water, there is a white lily that doesn’t look like a water one.

However, a new mystery replaced the solved one. What was this elongated panel — a cabinet door? a shutter? And if so, how many such panels were there? Only two (including the apparently lost left half of the scene) or a lot more? Both a window and a cabinet could be arbitrarily wide, and Carpaccio is known for his ability to masterfully create horizontal compositions (1, 2, 3).

4. El Greco: a fragment that changed everything

And again the story of another triptych of a hard lot. Probably, this picture, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was its central part. On the left, there was the scene of the Annunciation (now its largest part is in Madrid, and the upper part, depicting the choir of angels, is in Athens). And on the right — The Baptism of Christ, which is now in Toledo.It is possible that it was the incompleteness (El Greco’s most rapid brush strokes, general sketchiness) and fragmentarity (why is John the Baptist raising his hands?) that made this last painting by El Greco a fascinating masterpiece.

The Parisian artists of the early 20th century were very impressed with the painting. And especially Pablo Picasso, who, inspired by The Opening of the Fifth Seal, created his Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) — the painting that gave rise to Cubism.

5. Rembrandt: an unlucky move

Perhaps, this is the most egregious case in our article. In the 18th century, Rembrandt’s Night Watch was cut down in order to fit a new room when it was decided to be transferred from a militia headquarters (which commissioned the painting) to the city’s Town Hall.Compare the original painting with the copy: on the left of the original painting, two characters are missing.

Yet, Rembrandt’s paintings experienced even worse crucibles.

In 1656, he created The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Joan Deyman — a group portrait of surgeons, like the famous Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (actually, Deyman was Tulp’s successor as head lecturer of anatomy at the guild of surgeons). In 1723, a large part of the painting was destroyed by fire and only hands were left of Dr. Deyman, who was dissecting the brain of an executed criminal. And nothing more. The painting is now in Amsterdam Museum. And anyone who takes up the study of the work of Andrea Mantegna, will certainly use this fragment as the most famous quoting of his Dead Christ.

6. Delacroix: cut after the break

The portrait of the writer is now in Copenhagen. Portrait of the composer — in the Louvre Museum in Paris. But once they were together. In all senses.

You can come across this portrait, signed by Delacroix, on the web. In fact, this is a reconstruction created by an unnamed artist already in our century — a hypothesis about how a joint portrait of George Sand and Frédéric Chopin could look like.

7. Monet: a mouldy luncheon

Claude Monet decided to send his Luncheon on the Grass to the Paris Salon of 1866: three years before, they rejected the painting of the same name, created by Édouard Manet.Something went wrong from the very beginning.

Monet created the first, medium-sized version of the Luncheon. Then painted it on the larger canvas. But he left the painting a bit unfinished: he was disappointed. However, the artist didn’t throw his work away. In 1878, Monet experienced yet another financial difficulties (in fact, the painter lived in great poverty until he became famous): he owed a lot of money to a carpenter Alexandre-Adonis Flament, his landlord from Argenteuil. In 1878, Monet folded his Luncheon on the Grass and gave it to Flament as collateral for rent. Flament put the roll in a cellar.

When in 1884, Monet borrowed the necessary amount of money from his art dealer Durand-Ruel and repurchased The Luncheon on the Grass, it turned out that the painting had been badly damaged by damp and mould. The artist had to cut the large canvas up, having only two undamaged fragments. He would keep them until the end of his life, then they would go to his son Michel and, after being part of various private collections, would finally reunite at the Musée d’Orsay — only in 1987.

8. Manet: God-level marketing

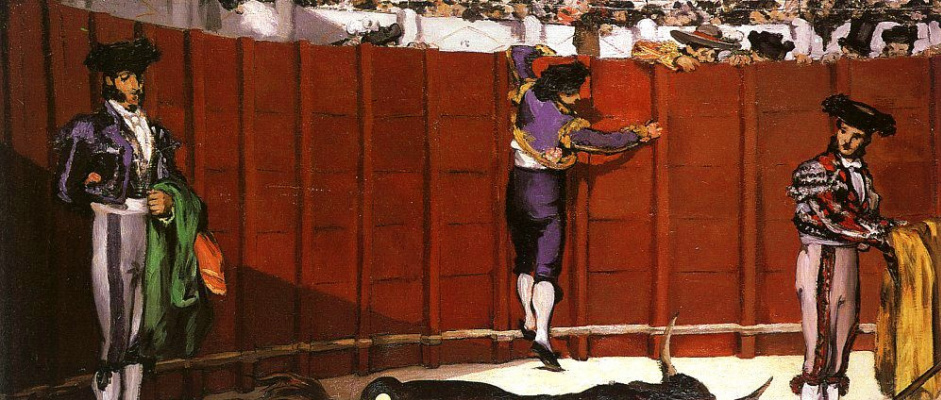

Édouard Manet sent his Episode from a Bullfight to the 1864 Salon. The audience laughed at the painting. Art critics breathed fire and brimstone. They made fun of Manet, who overcomplicated the composition and didn’t cope with the perspective. Comparing to rather large human figures, the bull looked small — more ridiculous than menacing. Hector de Callias from L’Artiste wrote: "the toreadors appear to be laughing at this little bull which they could crush under the heels of their pumps."Alas, it wasn’t about the critics not understanding Manet’s innovative techniques. Of course, they should have been filled with admiration for his bold palette. They should have admired Manet’s energetic brushstrokes, but kept talking about him painting pictures with a shoe brush. However, they were right about the composition, perspective and size. Manet understood that — and took a knife. However, he did not destroy the painting, but cut out two successful fragments from it, destroying both the composition and the perspective — that is, his mistakes. Instead of one objectively bad painting, he got two independent masterpieces: one of the fragments is now on display in the Frick Collection in New York, the second one — in the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

9. Degas: Madame Manet without a face

Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas were friends. Once Degas created a family portrait for his friend: Manet is reclining on a couch and his wife Suzanne, a talented pianist, is playing some melody (perhaps, a relaxing one). From the workshop of Degas, the painting moved to Manet’s house. The friendship continued.After some time, Degas came to visit Manet and saw that his painting was slashed with a knife — right across Susanne’s face. Degas was mad: "Who did it?" "Me," admitted Manet. No one knows if Manet explained why he did that. It is only known that Degas then took his damaged painting and left. Over time, the artists reconciled, but never became so close as before that incident. Degas was going to restore the painting but did not do it — he only sized the canvas sewn into the cut section and put a signature on it in the lower right corner. That variant of painting is exhibited in the museum.

Édouard Manet. Madame Manet at the Piano, 1868

Soon after damaging his family portrait, Manet himself painted his wife — in the same pose, at the same piano. Maybe he did it to apologize to Susanne for spoiling her portrait. Or taught Degas a lesson: that is how he should have painted her face.

First of all, when Édouard and Suzanne got married, 11-year-old boy Léon, who was either Suzanne’s younger brother or nephew, started to live with them. And Manet was his godfather. In fact, Léon was Suzanne’s son — and the couple kept it secret all their life. Those were the times when it was impossible to clear oneself from illegitimacy in hindsight. But the name of his biological father is another mystery: it could be Édouard Manet or his father (which would make the boy the artist’s brother). Suzanne gave piano lessons to the Manet brothers — and got pregnant from someone in that house: whether from the father, or from the eldest brother, that is from Édouard. Both Édouard and his father had a penchant for women. Both died from the effects of syphilis.

Secondly, other women. Just at the time when Degas was painting a family portrait of the Manet couple, Édouard was taken with artist Berthe Morisot. And it was not an ordinary affair, but a real big feeling.

10. Renoir: was there a bird?

Renoir’s little-known early work Woman Looking at the Bird is one of the most valuable pieces of the Nizhny Novgorod state Art Museum. This painting has been dealt a tough hand. It ended up in the USSR in 1945, along with dozens of other works that previously belonged to wealthy Hungarian Jews.It is assumed that this was the case: the Germans tried to bring the works taken away from the Hungarians back to Germany, but were forced to abandon a carriage with their treasures halfway — that is how the Red Army soldiers stumbled upon it. Of course, books and paintings from the so-called "Hungarian collection" became objects of both diplomatic negotiations and court sessions many times. Some of the trophies have already returned to the heirs of their previous owners. But this Renoir is still in Nizhny Novgorod.

Only in the title. In fact, this female portrait is just a fragment of a big painting. And we can see it as a whole: Renoir’s work was captured on a canvas of Frédéric Bazille — a talented Frenchman who would have also become a famous impressionist if he had not died in a war four years before the exhibition, which would be called the First Impressionist Exhibition. During their stay in Paris, Renoir and Manet lived and worked with Bazille, who kindly offered harbourage to them (the future stars were still poor beginning artists and did not have means to rent a house or a workshop).

We can only make wild guesses as of what happened to the painting and who was depicted on it naked. Our version is: the naked woman is the same Lise Tréhot. In six years of their relations, Renoir painted her at least 20 times and, according to the researchers of the artist’s work, most of the female figures in Renoir’s paintings of that period were painted from Lise.

Maybe he didn’t like what he created. Or he was not ready for a scandal — at that time it was still considered indecent to portray mere mortals naked; only ancient goddesses deserved to be painted without clothes. Renoir knew that and was not yet ready for a creative compromise. At the same time, he painted Lise nude on the river bank. But at the last moment changed the work: he rendered Lise as the Roman goddess Diana the Huntress, adding a loincloth, a killed doe and a bow so that the work was not faulted for obscenity and could be exhibited at the Salon (it didn’t help — the jury of the Salon still rejected Diana).