1. The origins of the artistry

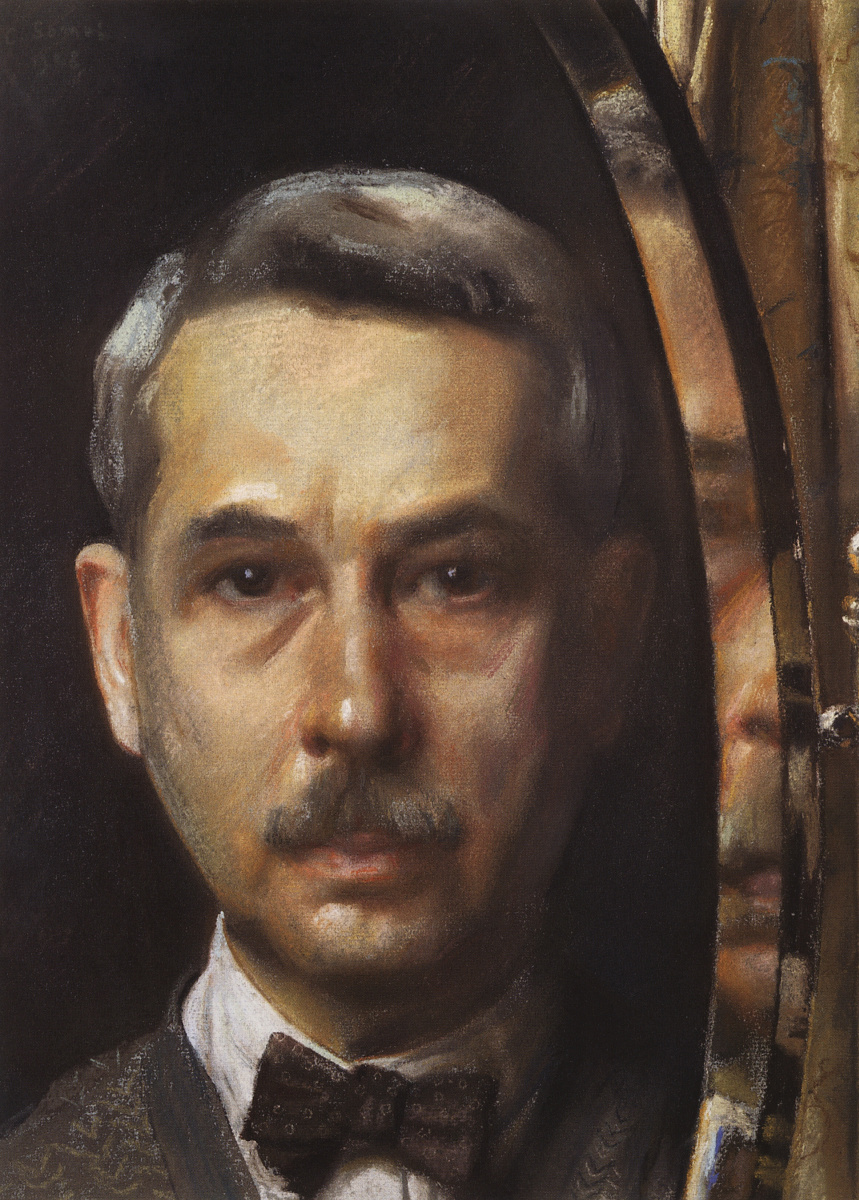

To begin with, Konstantin Somov’s desire to become a professional artist was supported in every possible way by his family. His father, Andrei Ivanovich Somov, was a famous museum figure, the Hermitage curator, and the young Somovs were surrounded by art objects and talks about art from their childhood. The eldest son, Alexander, became an art critic, while Konstantin and Anna became artists.A descendant of nobles of ancient standing, Andrei Somov was forced to build his career on his own and achieved great success on this path. A graduate of the Physics and Mathematics Faculty of St. Petersburg University, he worked for several years as a tutor, teaching mathematics, and found time for painting, which he adored. Under his leadership, cadets of the Marine Corps and students of the Mining Institute learned the wisdom of mathematical sciences, and at the same time, there remained time to study art and publish in the Picturesque Russian Library magazine. Andrei Ivanovich showed his scientific mind and language skills in translating Galileo’s works into Russian. And his love of art manifested itself in the creation of an etching guide, which he learned from one of the students of the famous engraver, Nikolai Utkin. From their early age, children of Alexander Ivanovich absorbed the history of art and drawing lessons, communicated with famous artists and art critics who often visited the house.

2. Neva Pikwikians and meeting like-minded people

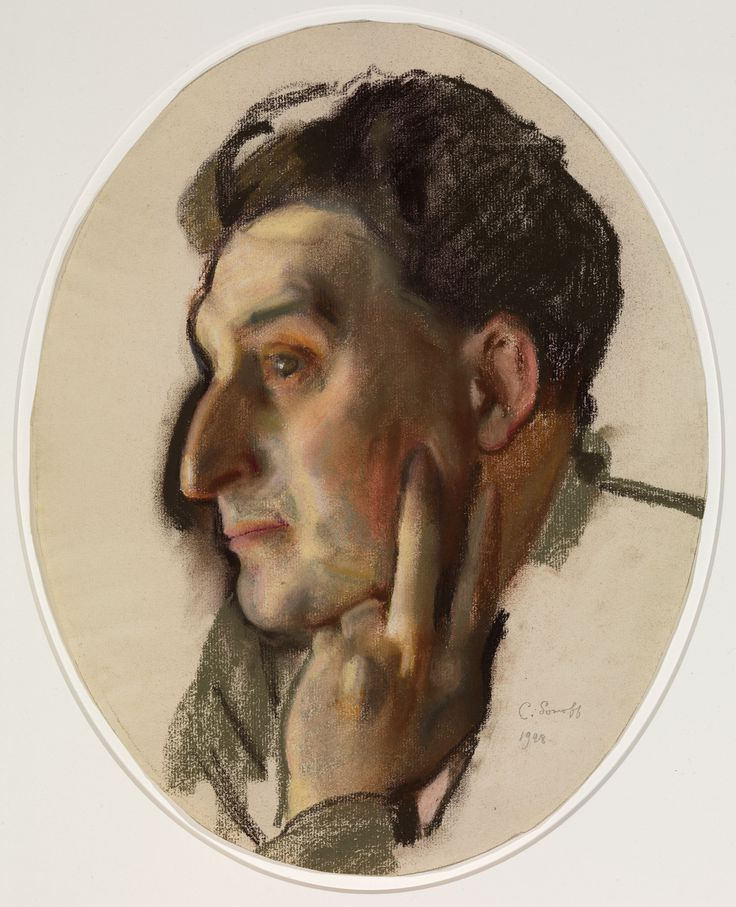

While studying at the Karl May School in St. Petersburg, an advanced educational institution for its time, Konstantin Somov met and became close to Alexandre Benois, Walter Nouvel, Dmitry Filosofov. Even then, the young gymnasium students began to think about a new art, different from the emasculated academicism. In 1887, they formed the Neva Pikwikians circle, at their meetings, they studied art history, painting and music. Later, Sergei Diaghilev and Léon Bakst joined the Pikwikians. Thanks to the energy and talent of Diaghilev, the small group of the art lovers, named after the first novel by Charles Dickens, grew into a more respectable group, Mir Iskusstva. It was joined by Moscow artists Konstantin Korovin, Valentin Serov, the Vasnetsov brothers, Mikhail Vrubel and Mikhail Nesterov.3. In Paris

In 1888, Konstantin Somov entered the Imperial Academy of Arts. In order to see the masterpieces of European museums, he did not have to fight for a pensioner prize, because the Somovs regularly went on vacation abroad. Little Kostya saw Paris for the first time when he was only nine years old. Museums and theatres were part of the family’s compulsory program, which was greatly facilitated by the artist’s mother, Nadezhda Konstantinovna, who received an excellent musical education. While studying at the Academy, Somov visited Europe again — first accompanied by his mother, and later with his father. We can only imagine those fascinating excursions Somov Sr. conducted for his son when they visited the famous museums of Italy and Germany.…In 2006 and 2007, the works by Konstantin Somov set records at the Christie’s auction of Russian art in London: the Russian Pastoral painting (1922) was sold for amount of £ 2.4 million, which became a record sum for the artist’s work at that time. A year later, another work by Somov, Rainbow, was auctioned for 3 million 716 thousand pounds with a starting price of 400 thousand pounds.

4. Gauguin and Cézanne through the eyes of Somov

In Paris, Somov created portraits of his father and his sister Anna, as well as Arbor, In August, Rainbow, Confidentials paintings. And this is how he spoke of what he saw in local galleries: "I really liked Gauguin, but not Matisse. His art is not art at all!" Cézanne also got it: "Except for one (or maybe three) beautiful still lifes, almost everything is bad, dull, without values, in stale colours. His figures and his naked "bathers" are very filthy, mediocre, inept. Ugly portraits." And even Van Gogh was rejected: "Not only not brilliant, but rather not good."5. Mir Iskusstva and the first steps in illustration

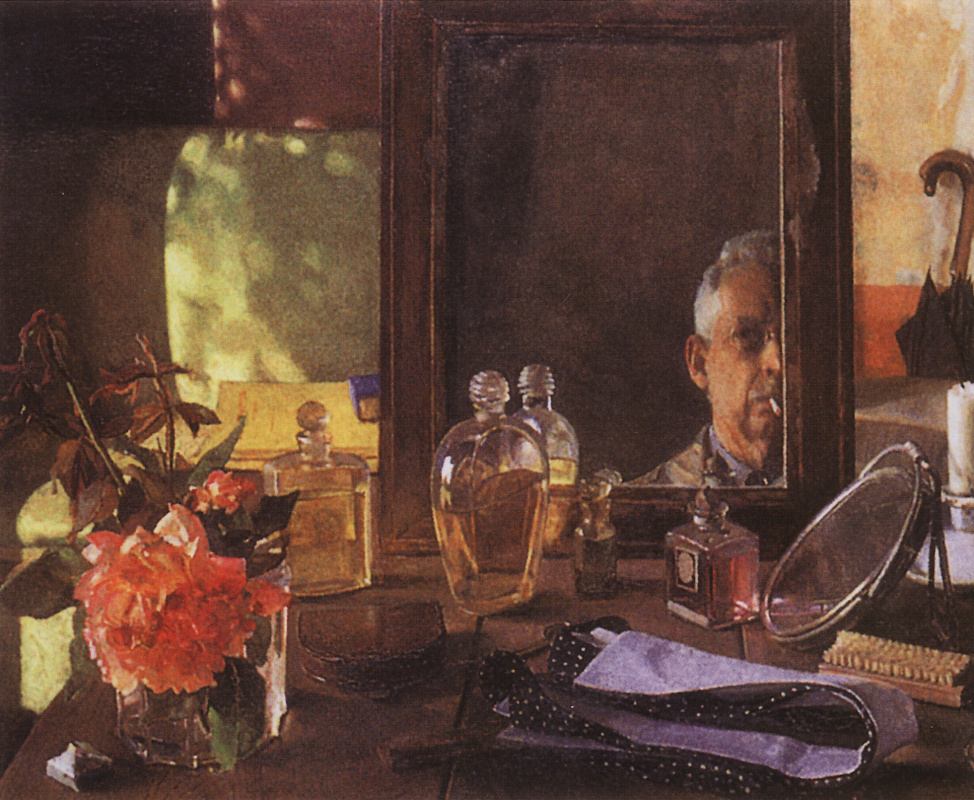

Thanks to the energy and talent of Sergei Diaghilev, the small group of the art lovers, named after the first novel by Charles Dickens, grew into a more respectable group, Mir Iskusstva. Diaghilev, who already was fond of collecting paintings by that time, organized an exhibition in St. Petersburg in 1898. Later, the exposition had place in Munich, Düsseldorf, Cologne and Berlin.6. Diary as a companion of a true dandy

Keeping a personal diary at the end of the 19th century was fashionable. Somov, like many of his colleagues, kept daily notes, trusting the diaries not only with his own innermost thoughts, but also describing the works that he drew, compiling a kind of a catalogue raisonné. Somov apparently destroyed the notes of his youth himself; the notes, which have come down to us, he took from the age of 25. Somov not only wrote, but also re-read his diary, his notes became more and more interconnected and literary perfect. Sometimes he read excerpts to his sister Anna, sometimes to his life partner Methodius Lukyanov; however, the latter did not like these "seances". Without a doubt, the artist wanted the diary to be published after his death, and even rewrote some parts of it in his declining years.Konstantin Somov. Portrait of the composer Sergei Vasilievich Rachmaninoff. 1925

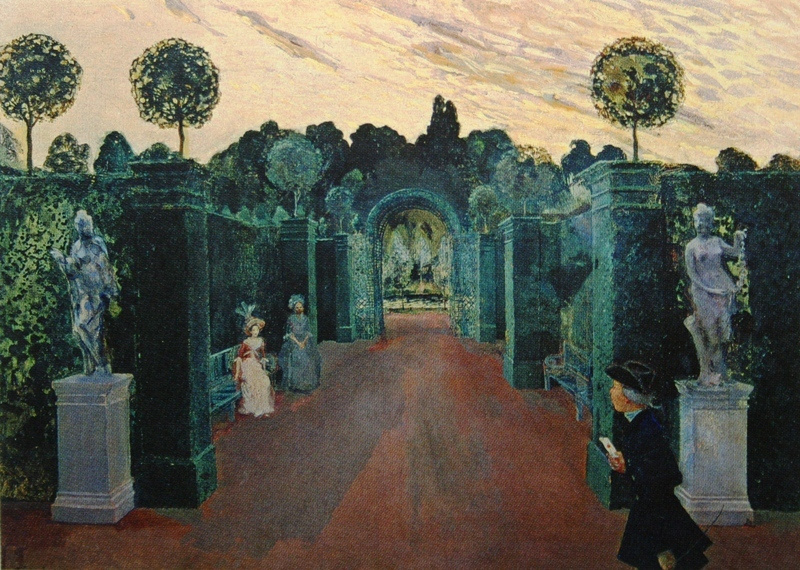

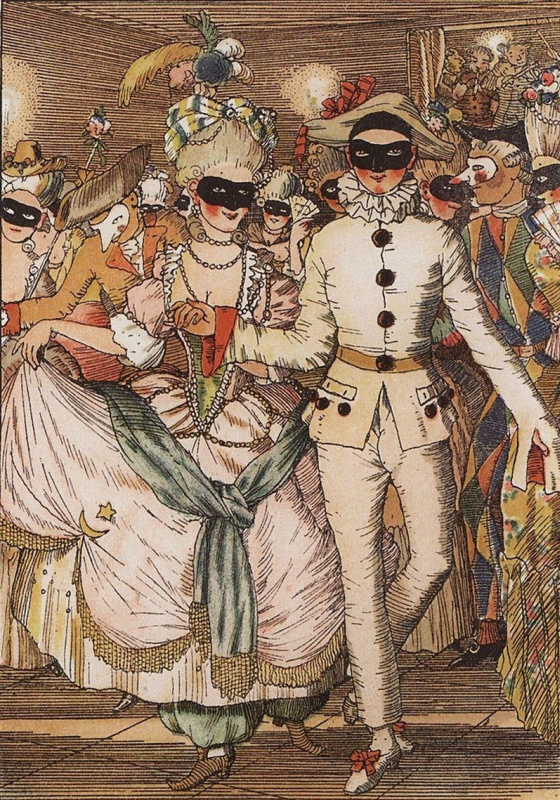

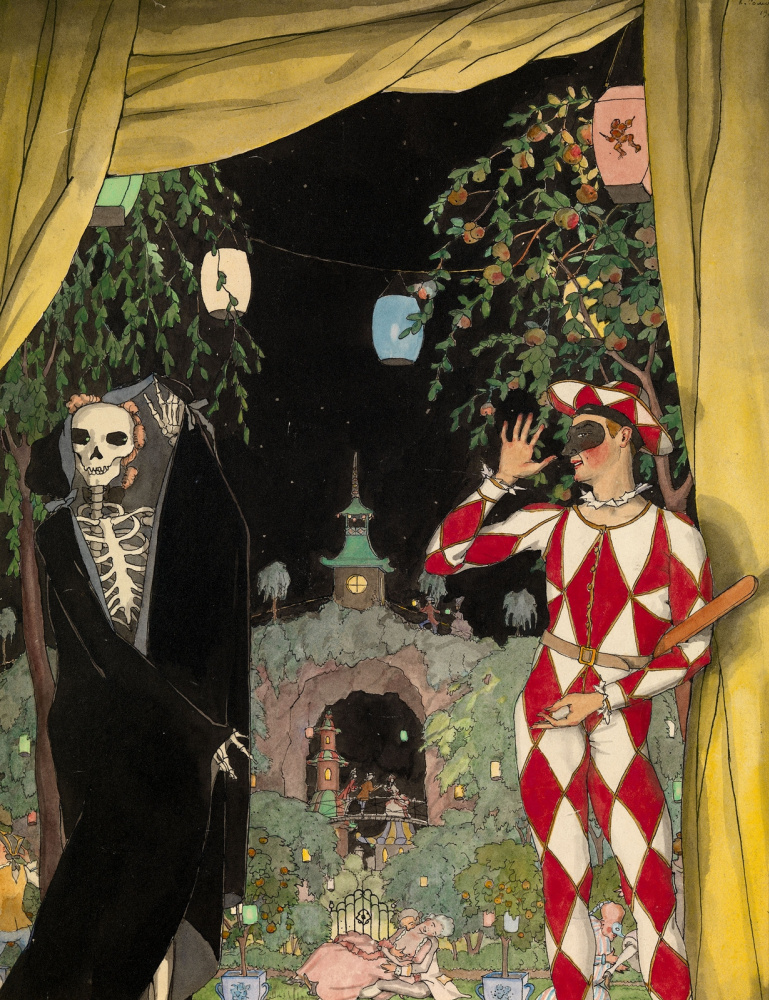

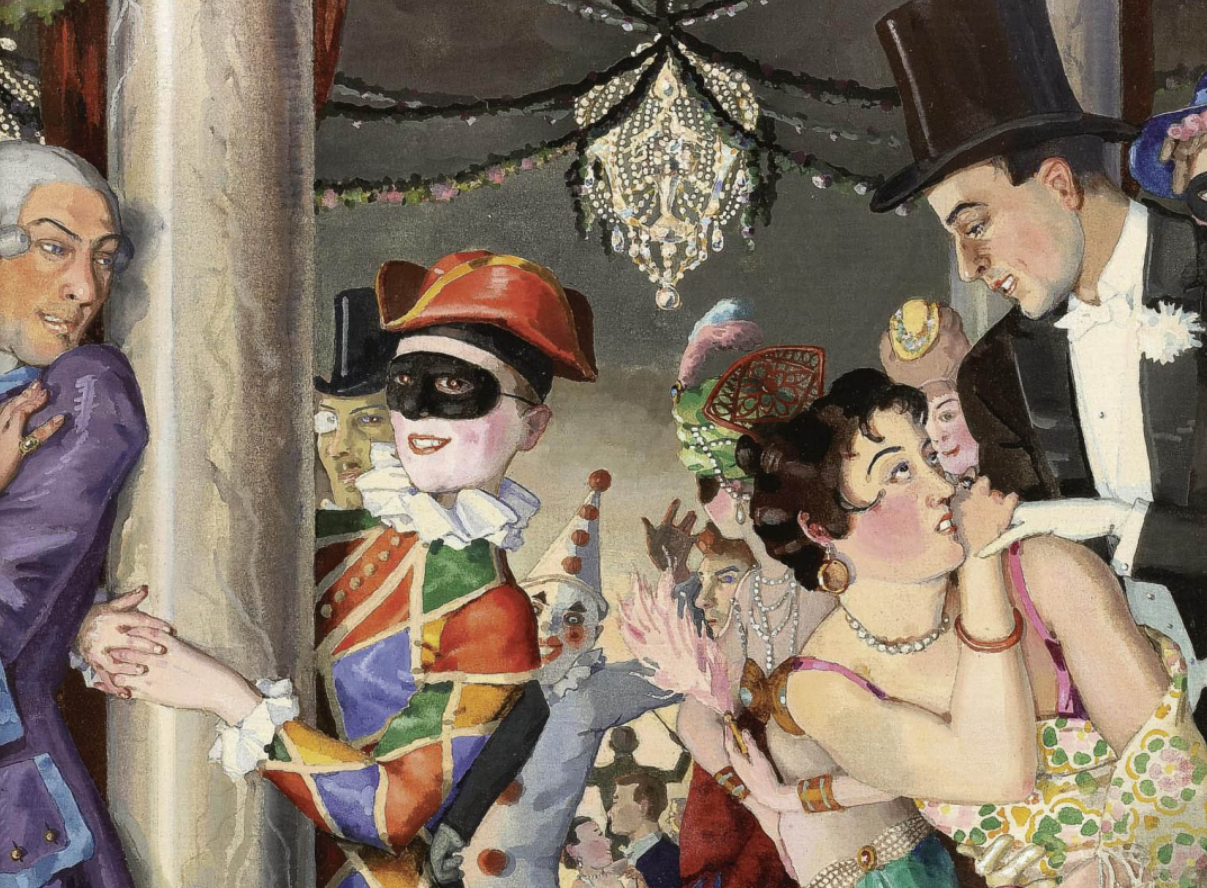

Konstantin Somov showed himself brightly both in portrait and landscape genres, showing the world his remarkable talent and brush mastery. Nevertheless, one of the artist’s stocks in trade is erotic illustrations for the courtly collection, The Book of the Marquise, which collected an anthology of French erotic literature of the 18th century.

7. The courtly Book of the Marquise

Somov himself did not like his illustrations for the Book of the Marquise much. In his diary, one often encounters such phrases: "I'm tired of them, these graphics, in which I’m so awkward," and "a venal, frivolous thing". Nevertheless, it was the fashionable eroticism of the illustrations for this collection that made Somov popular. The renowned bibliophile and art critic Erich Hollerbach called The Book of the Marquise the highest achievement in Somov’s graphic art. "Here… the dream cult of the 18th century is reflected, with its charming shamelessness, frivolity and intense sensuality," wrote Hollerbach.This collection, the idea of which belongs to the Austrian essayist and critic Franz Bley, contains an anthology of French erotic literature of the 18th century: Voltaire, Casanova, Chenier, Parny, about fifty authors in total. Actually, Bley ordered the illustrations for The Book of the Marquise to Somov. The book was first published in German by the Hans Von Veber publishing house in 1907, and later it was reprinted several times, in particular, in 1918 in St. Petersburg.

8. Revolution and emigration

After the demise of Tsar Nicholas II, Somov wrote in his diary: "There are so many events in two days. Nicholas has been dethroned, we’re going to have a republic. My head is spinning. I was so afraid that the dynasty would remain. I saw how the royal coats of arms were knocked down from signboards everywhere. This morning I called Benois, advising him to take power in the field of art right away. He told me that Roerich, Grzhebin, Petrov-Vodkin had already conceived something with the assistance of Gorky… It is better for me not to interfere and live as I used to". Despite all this, Somov still decided to leave the country. And only in 1923 he succeeded — he left for America as an authorized representative of the Russian Exhibition, which he successfully held in 1924. Konstantin Somov did not return to Russia. In January 1928, he settled in Paris, having bought an apartment on Boulevard Exelmans, and immersed himself in work — he painted portraits, landscapes, miniatures, and created a series of wonderful watercolour works.9. Mif: the heart friend

In September 1910, Konstantin Somov met a young model, Methodius Lukyanov. Methodius, or Mif, as his friends called him, turned 18 at that time. Mif was not only a friend and assistant for Somov; over time he became his "son, brother and husband" and settled in the Somovs' house. Somov’s short romance with the British writer Hugh Walpole, who also lived in the Somovs' house in 1916—1917, did not destroy, but rather strengthened the relationship between Somov and Mif. After the revolution, Lukyanov was the first to emigrate; in 1922, he found out that he was sick with tuberculosis, and he went to Paris by hook or by crook, to get to the doctors there. Mif bought a farm in the Norman town of Granville, was engaged in breeding and selling chickens, ducks and rabbits. Picturesque landscapes, fresh air, silence and simple work prolonged the life of Methodius. Somov often came to visit him from Paris; their life was calm and resembled that of a family.Somov continued to live, paint nudes, keep a diary, hiding intimate moments with simple codes and allegories, records in foreign languages.

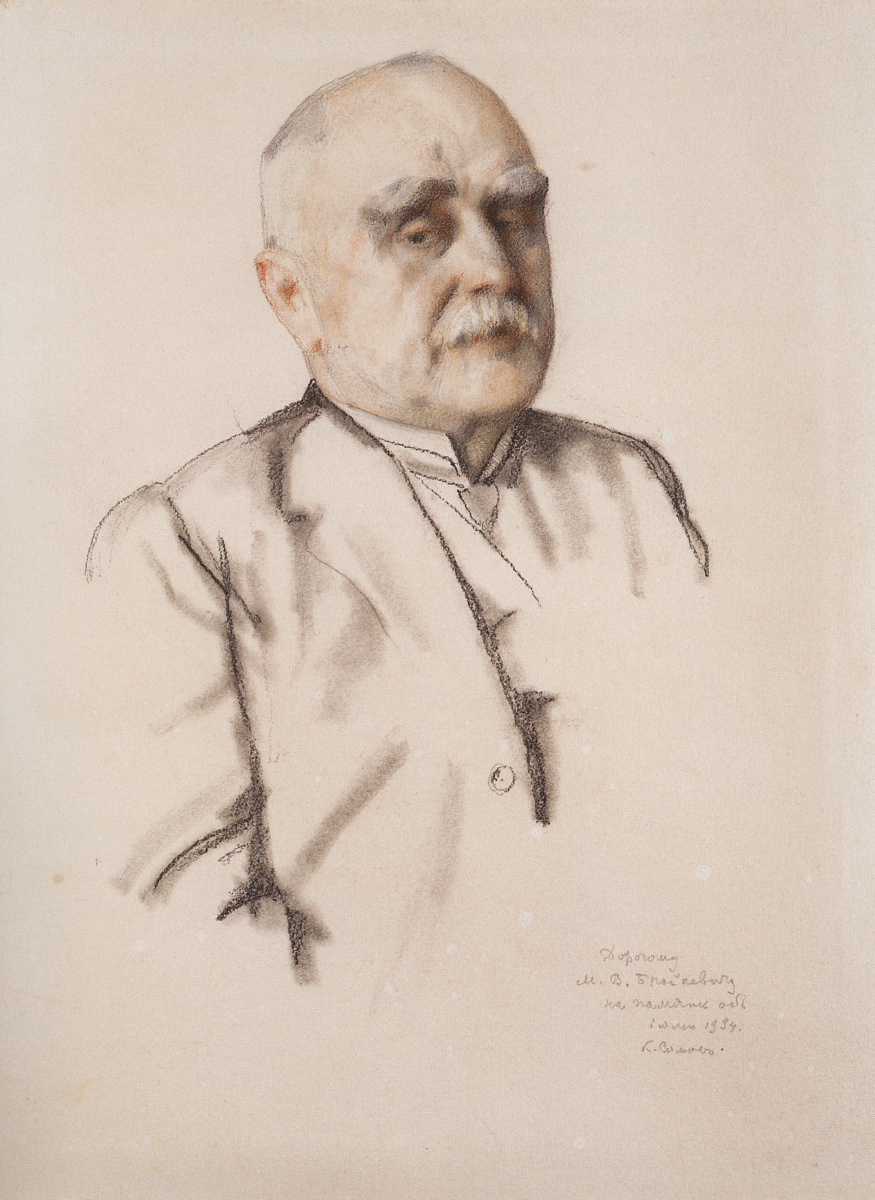

10. An admirer, a friend, an executor

One of the great admirers of Konstantin Somov’s talent was Mikhail Vasilyevich Braikevich. A graduate of the Institute of Railways, a talented engineer, Braikevich worked at many imperial construction sites. Braikevich was also a passionate admirer of the works of Russian artists, miriskusniki. An enthusiastic collector, vice-president of the Odesa Society of Fine Arts, he always stated that he bought paintings not only for himself personally, but in order to create a collection intended as a gift to Odesa.The review was prepared based on the publications of the Arthive authors, information from the mentioned museums.