Gala and Salvador Dalí

Against all the odds. When Gala and Salvador Dalí met in 1929, there seemed to be quite serious obstacles in the way of their relationship: she was ten years older than him, had a husband, the poet Paul Éluard, and a daughter from him. None of these could stop 25-year-old Dalí. The Russian émigrée captivated him completely. Later, he wrote, ‘She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife.' However, for Dalí's father, this romance was something scandalising — enough to cut off all contact with his son and stop giving him money when the lovers got married in 1934. Their marriage, though, as if to put naysayers to shame, lasted till Gala died in 1982.Salvador Dalí. The first version of The Madonna of Port Lligat. 1949. The Haggerty Museum of Art, Milwaukee

Muse and manager. The love that united them was far from conventional. Gala believed that Dalí was a genius, and he saw her as the source of all his creative inspiration and energy. For him, she was both a muse and a model, and was glorified as the Virgin Mary in his canvas The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949). She did not mind being number two in public, yet her husband’s success was largely due to her management of his sales, exhibitions, and finances.

Unorthodox agreements. Dalí made no secret of his phobia of sexual relationship. The problem was tackled by means of open marriage. The artist, not occasionally, encouraged his wife to find other sexual partners for herself. As the years went by, though, the situation only grew tense. The more time and money Gala spent on her lovers, the more Dalí was afraid of breaking up. At times, things even got so bad that there were acts of mutual violence. For decades, the painter lived bearing a grudge against his wife, but still, when she died at eighty-seven, he was utterly devastated. The rest of his life he spent in self-isolation.

Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Concharova

Open your eyes. They were born in 1881, their birthdays being a month apart — Mikhail Larionov's on 3 June, Natalia Goncharova's on 3 July. They went to the same School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture in Moscow. It was there that they met — to fall in love with each other. He was the first to realise that she was a painter by vocation, not a sculptor — ‘Yours is an eye for colour, but you are too preoccupied with form. Open your eyes to see your own eyes!'Late marriage. There was everything. There were scandalous escapades, arrests of Goncharova and her paintings for pornography, Larionov’s expulsion from the School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, Avant-Garde societies, friends with future-oriented minds always seeking innovations in art. The couple were only driven by practical reasons: they both wanted their common legacy, all their works, collection, and papers, to be preserved and returned to their motherland.

The tried and trusted Shurochka. Alexandra Tomilina (Shurochka), Larionov’s dear one, helped the married couple till Goncharova’s death in 1962. The following year, Larionov married her, and made her the heiress to his and Goncharova’s archive. He entrusted Shurochka to have their entire legacy taken back to the USSR.

Marina Abramović and Ulay

Extreme intimacy. Abramović, a performance artist from Yugoslavia, and Uwe Laysiepen (Ulay) from Germany met in Amsterdam in 1976. They immediately started working together, and formed a collective named The Other. The pair referred to themselves a "two-headed body" and claimed to feel as close as twins.Trust-trying exercises. Together, the young artists invented a series of extremely intimate tests to try physical endurance and emotional trust. In one of their performances, Rest Energy (1980), Abramović was holding a bow, and Ulay its bowstring drawn tight, with an arrow pointed at her heart. Later, she recalled, ‘We actually held an arrow on the weight of our bodies, and the arrow is pointed right into my heart. <…> It was a performance about the complete and total trust.'

Public reunion. Decades later, in 2010, the two met again during Abramović's MoMA retrospective where she performed The Artist is Present. During the performance (which resembled Nightsea Crossing), Ulay, quite unexpectedly as it seemed, sat down in front of her at the opposite end of the table. The deeply emotional moment brought them both to tears. Still, the discord remained: Ulay sued his former partner and accused her of having not paid him his royalties. In the years that followed, he claimed she was not to be credited as his co-author. However, after 2017, the pair seem to have put their past behind them.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Crosspoint Paris. He was born in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, she in Casablanca, Morocco. But it was Paris that brought them together. In October 1958, Christo Javacheff, a refugee who was then living in the City of Light, was commissioned to paint a portrait of Jeanne-Claude's mother. By that time, Jeanne-Claude Denat had been engaged. She did get married later, but in the end, she followed her heart and left her husband before their honeymoon was even over — to be with Christo.

Christo’s project of draping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris (2018). Photo from: christojeanneclaude.net/André Grossmann

The two Geminians. Both artists were born on the same day, 13 June 1935.

The art of disguising. The married couple’s creative duo got famous due to their large-scale art works made of fabric, which included The Gates in New York City’s Central Park and the epic 24 mile-long Running Fence. Besides, they draped fabric over such iconic architectural landmarks as the Reichstag and the Pont Neuf bridge. The couple insisted that the only purpose of their art was visual impact.

Nota bene. For decades, Christo credited himself as the single maker of the installations they created together. But since 1994, all their co-projects have been retroactively credited to "Christo and Jeanne-Claude."

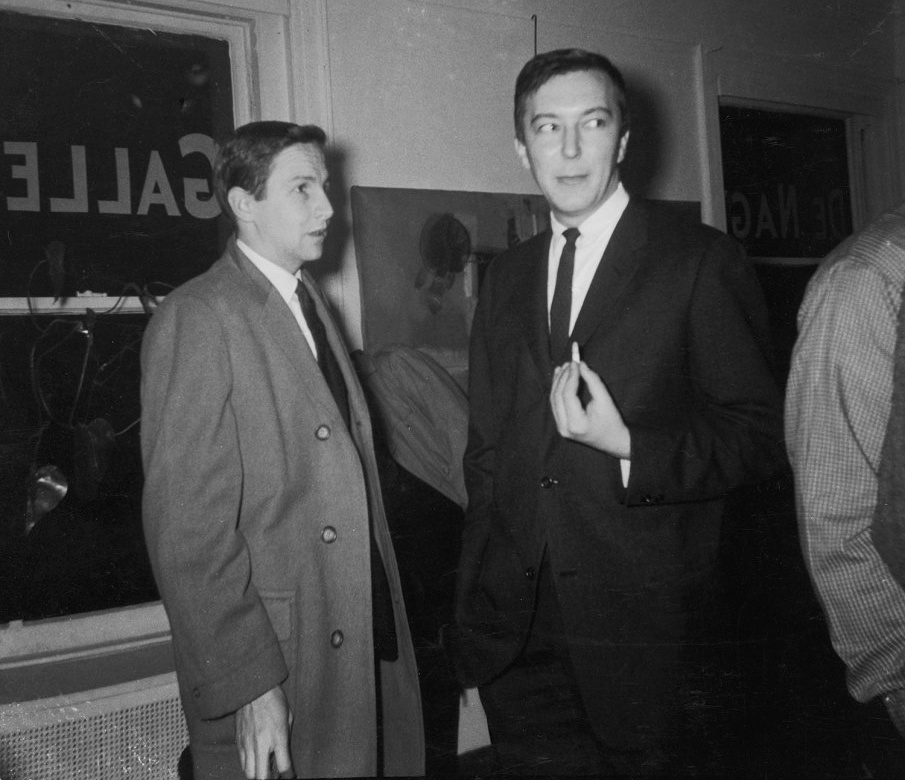

Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns

The downtown dreamers. Perhaps, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were the "New-Yorkest" of all couples, though actually, they were only together for five years, 1956 to 1961. They had their studios on different floors of the same industrial building in Pearl Street, and lived for some time in Lower Manhattan along with other artists (among them Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly).Opposites attract. Rauschenberg was sociable and talkative, Johns reserved and a bit detached. Despite these differences, the two united to reduce the dominance of Abstract Expressionism . Rauschenberg’s "combines" and Johns’s series of Flags and Targets offered new possibilities to get away from the egoism and individualism of the aesthetic traditions of their era.

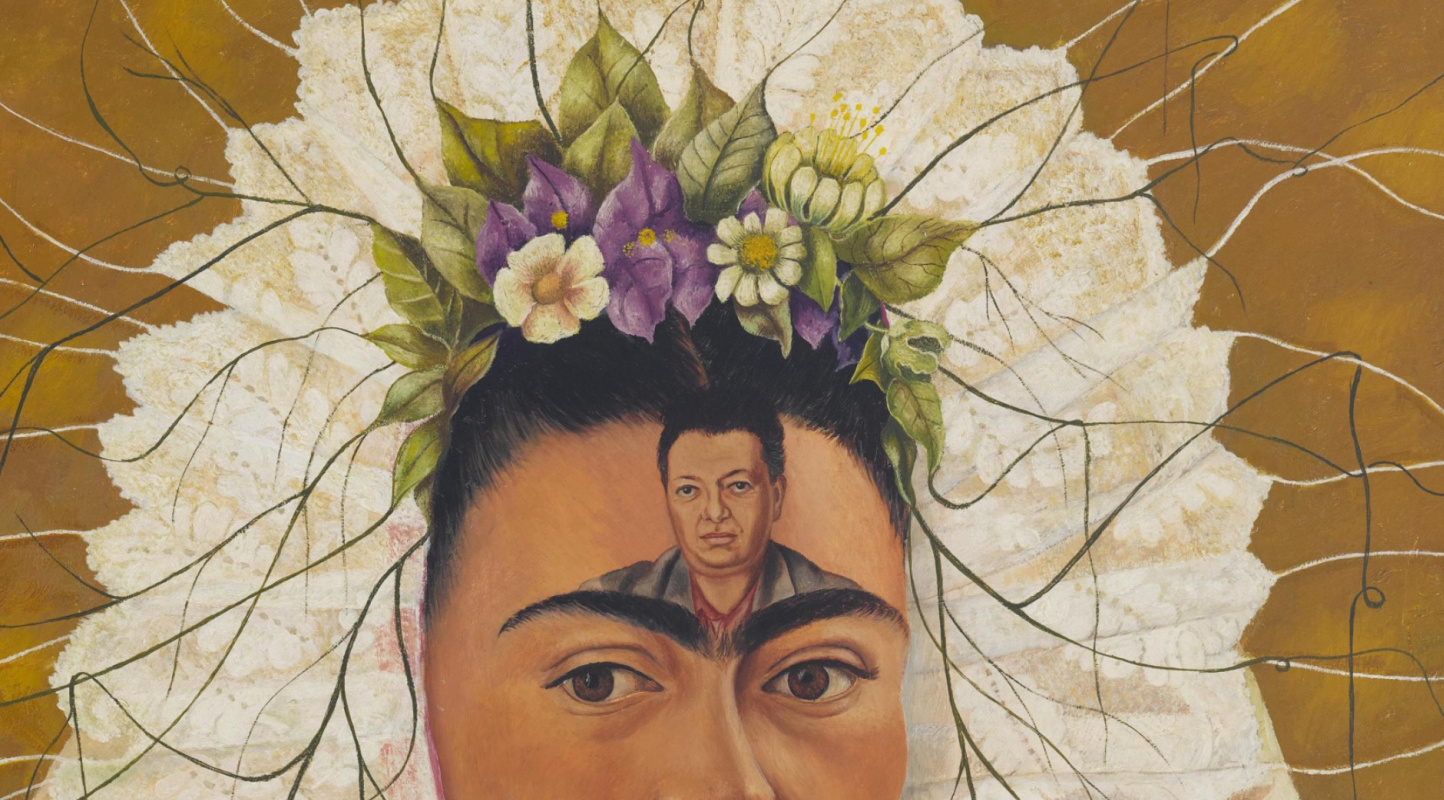

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

Epic proportions. There is hardly a greater and more tempestuous romance in the history of art than Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera's. Kahlo was a student when she met Rivera, who was 20 years older than her and had the reputation of being a titan of Mexican art. The girl’s parents disapproved of her love and scornfully termed the couple "the elephant and the dove," thus directly alluding to the disparity between their sizes.Frida Kahlo. The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Myself, Diego, and Señor Xolotl. 1949. Jacques & Natasha Gelman Collection, Mexico City

The art of adultery. Rivera and Kahlo admired each other’s talents. Their relationship was a whirlwind of supporting each other in their art and mutual attraction coupled with infidelity on both parts. Kahlo made no secret of her bisexuality. She had liaisons with women as well as with men (a well-known example of the latter was Leon Trotsky). However, Rivera carried it too far having an affair with Kahlo’s younger sister Cristina, which left the paintress feeling absolutely devastated.

He said, she said. The couple got divorced in 1939. However, passion and admiration resulted in their remarriage. Rivera once called Frida "the most important fact in my life." And she said, referring to the traffic accident that had nearly killed her, "There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley, and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst."

Françoise Gilot and Pablo Picasso

The restaurant encounter. In May 1943, Pablo Picasso, then 61, met 21-year-old Françoise Gilot who had come with her friends to the Parisian restaurant Le Catalan. The painter was having dinner there in company with Dora Maar, who was then his mistress. Nevertheless, he walked over to Gilot’s table, offered her a bowl of cherries, and invited her to visit him in his studio.Three is a trend. Gilot became the object of Picasso’s affection when he had not split up yet with Maar, who, in turn, had won his heart when he was still living with his young French mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. (And 17-year-old Walter drew the artist’s attention in the period when he was on the verge of breaking up with his wife, the Russian ballet dancer Olga Khokhlova.) The young Gilot was ecstatic over the celebrated master, still she conducted herself quite sensibly for the reasons she explained later, "I came onstage with an unavoidably clear vision of three other actresses who had tried to play the same role, all of whom had fallen into the prompter’s box."

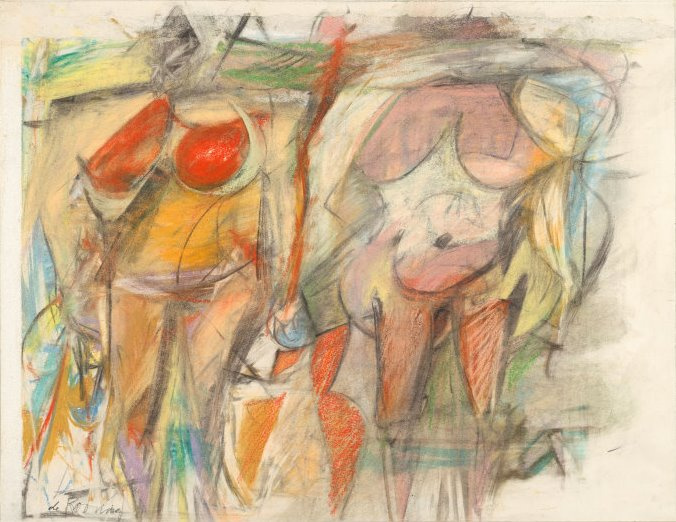

Elaine and Willem de Kooning

The stowaway and the student. Born in Holland, Willem de Kooning arrived in the United States illegally, as a stowaway on a British vessel headed for Argentina. In America, he immediately plunged into the world of art. His life changed forever in 1938 after a new student, Elaine Fried by name, enrolled in his drawing class. Willem, though reserved and obsessed with work, was seemingly struck by the charm of the woman who would later become his wife.Ahead of her time. Perhaps, Elaine lived ahead of her generation: she absolutely refused to give up her art and keep house instead, and she believed that her career was no less important than her husband’s. Besides, she was style-minded, and though the couple were known to be living on coffee and nothing else, she never failed to keep up with the latest fashions.

Yayoi Kusama and Joseph Cornell

Was or was not? Although free love is a language Yayoi Kusama has a command of, she never reveals the details of her romantic life. The Japanese paintress moved to New York City in the late fifties. Soon, she made friends with Donald Judd, who, like her, was then just starting out in his career. He, who would later be called the father of minimalism, spoke favourably of her first solo exhibition in 1951, and even purchased one of her paintings. Then, they rented their apartments and studios on different floors of the same building in 19th Street. Kusama called Judd her "early boyfriend," but they were only destined to remain friends. Her New York life was dominated by intense (though, perhaps, platonic) relationship with Joseph Cornell, an assemblage artist.

Yayoi Kusama and Joseph Cornell in 1970. Photo from: Artnet. News/Courtesy of Yayoi Kusama Studio, Inc.

Odd couple. Kusama was over thirty, when she met Cornell, who was 26 years her senior. They had years of an absolutely singular relationship. She regularly visited her friend at his mother’s place, where he lived and worked. Kusama and Cornell had a deep emotional bond: he would call her countless times a day, write long letters to her, and give her his works to sell when she was short of money.

The disapproving mother. We will hardly ever learn this part of the story, but rumour has it that Cornell’s mother was a bossy woman obsessed with controlling things. She was, reportedly, so angry about her son dating a much younger girl, that once she poured a bucket of water over the two artists, who were kissing in her backyard.

Dorothea Tanning and Max Ernst

Checkmate. Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning first met when he visited her studio at the request of Peggy Guggenheim, his then wife, who was interested in Dorothea’s Surrealist works. Ernst and Tanning, both chess enthusiasts, sat down to play a few games, and a week later, he moved to live with her.Two times two. Tanning and Ernst got married in Hollywood, in a double wedding with their friends, the artist Man Ray and the dancer Juliet Browner.

Some figures. Tanning and Ernst’s marriage lasted from 1946 till his death in 1976. He was her one and only husband, she was his third wife, and besides, he had had a long relationship with Leonora Carrington, a Surrealist painter.

Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz

Modernist American love. The celebrated photographer Alfred Stieglitz and the pioneering American artist Georgia O’Keeffe were married from 1924 till his death in 1946. He was older than her, lived in New York City, and owned the gallery 291, a centre to promote Modernist art.Messy situation. A womaniser, Stieglitz was fond of young women and supported promising women artists. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz revered each other’s intellect and art, but their marriage was hardly a happy one, as a great deal of it they lived separately.

Instead, while making her trip, she found a home.