Aristocracy and dark family secrets

The best friend of the poor artists and demi-mondaines of Paris was born in the ancient aristocratic family of Languedoc and received the sonorous name of Henri Marie Raymond comte de Toulouse-Lautrec Monfa. According to the descendants of this glorious family, the count family of Toulouse-Lautrec traces its origin from the Viscounts of Lautrec, who appeared on the territory of the County of Albi in the 10th century. Representatives of this family actively participated in the political life of the region, and some found their vocation far beyond the borders of their homeland. Thus, Count Joseph-Pierre de Toulouse-Lautrec (1727—1797) fled to Russia, fleeing the Great French Revolution, and made a successful career in the Russian army. His grandson, Count Valerian Alexandrovich (1811−1881), was also a military officer with the rank of lieutenant general and head of the Caucasian cavalry division. So the relatives of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec can be found in Russia.Illness made him an artist

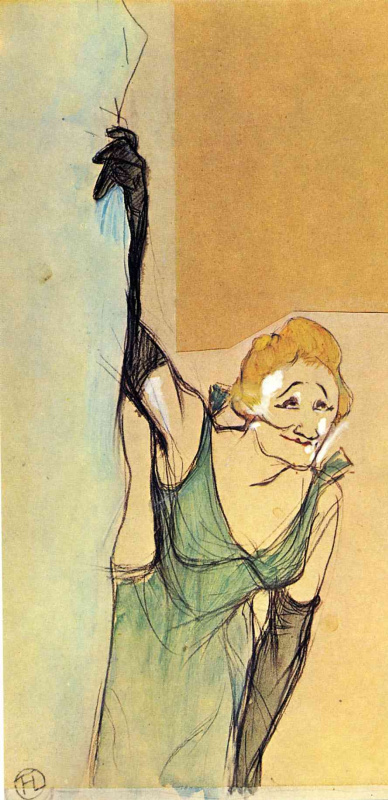

Perhaps it was precisely the close relationship in the aristocratic family that explained a series of health problems for the young Toulouse-Lautrec. As a child, he was often ill, it took him long to recover, and he was said to suffer from a congenital bone disease. At the age of 13, he fell from a chair and broke his left femoral neck, later his right one when he fell into a ditch. After that, Henri’s legs stopped growing forever, remaining 70 cm long, and Toulouse-Lautrec himself became a rather short man, 152 cm.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. 1894. Photo by Paul Cescu. Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, Albi, France. Source: wikimedia

For his mother, Countess de Seleiran, this became a terrible tragedy, as well as for the future artist himself: the physical peculiarity prevented almost everything that a young aristocrat had to do — dances and balls were no longer available to him, most sports too, a romantic relationship with a befitting girl of similar origin, like the military career, were impossible.

However, Toulouse-Lautrec himself did not lose his presence of mind, he easily joked about his illness, and turned the long periods of recovery from illness into an opportunity to practice painting and graphics. Studying art did not let him get bored and instilled hope.

Enfant terrible de la Belle Époque

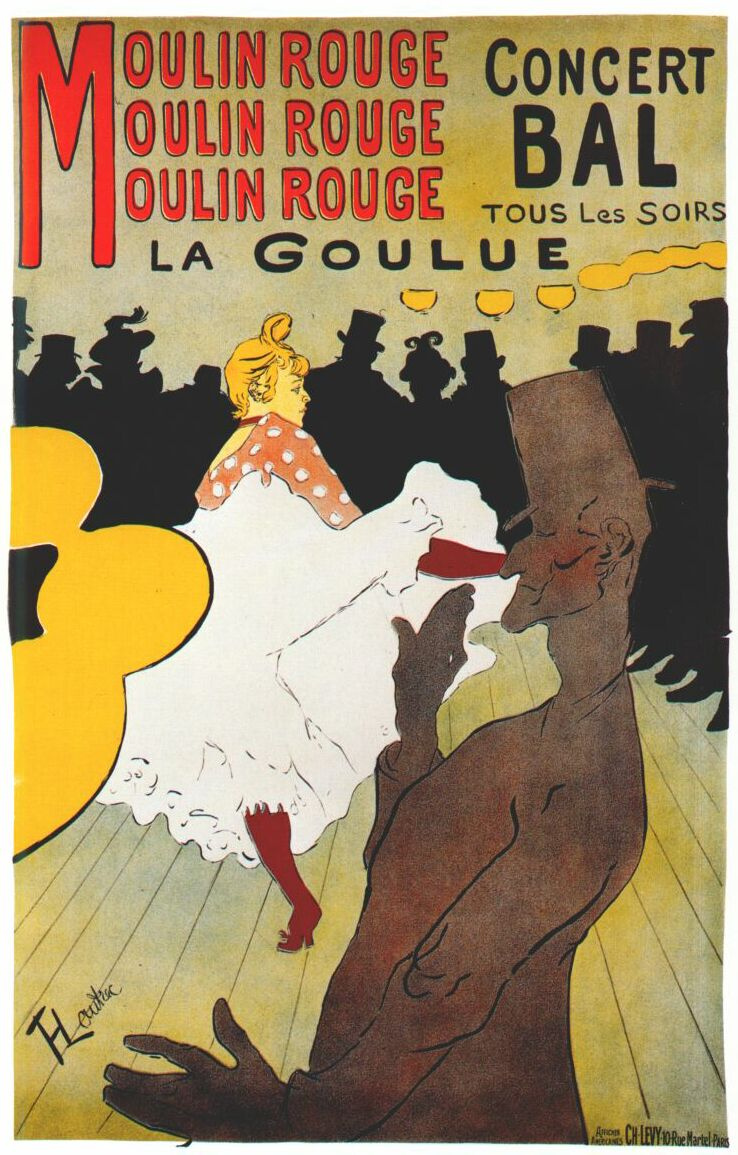

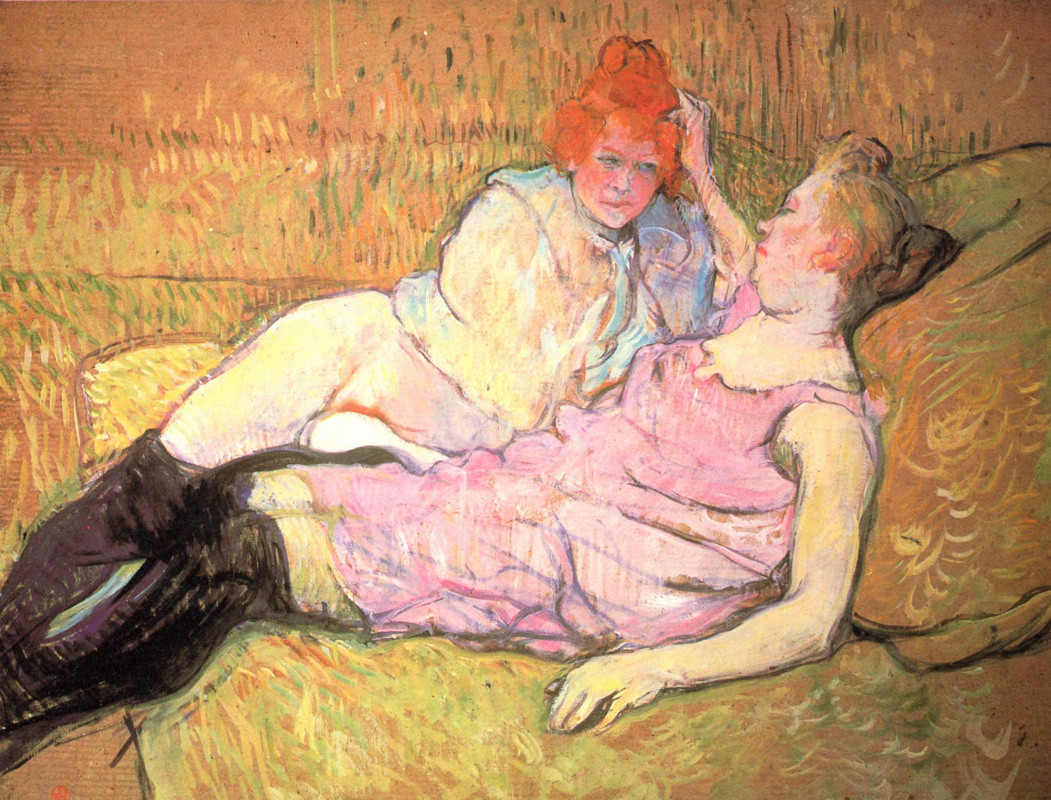

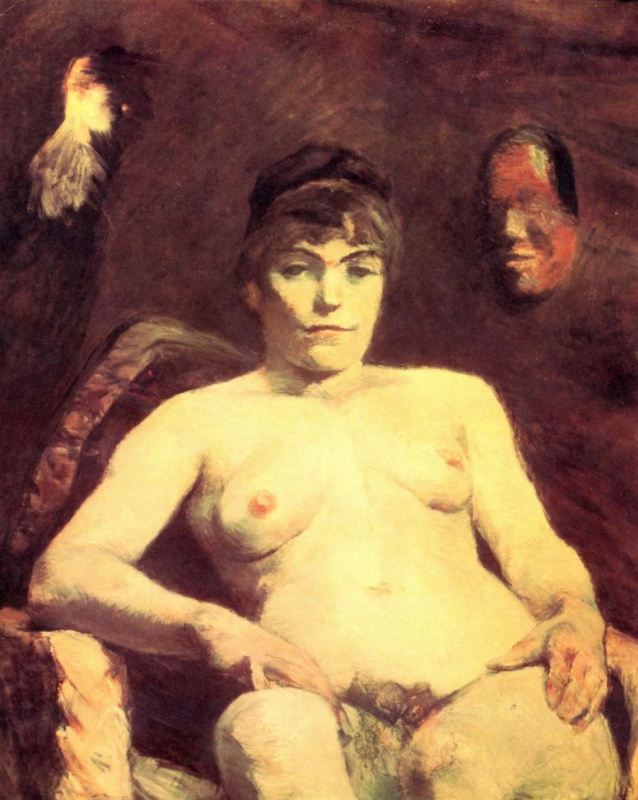

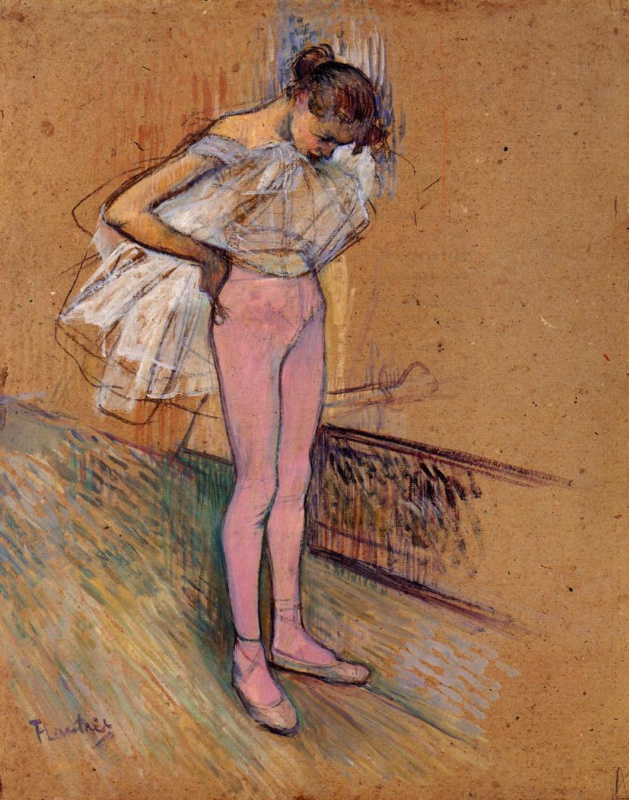

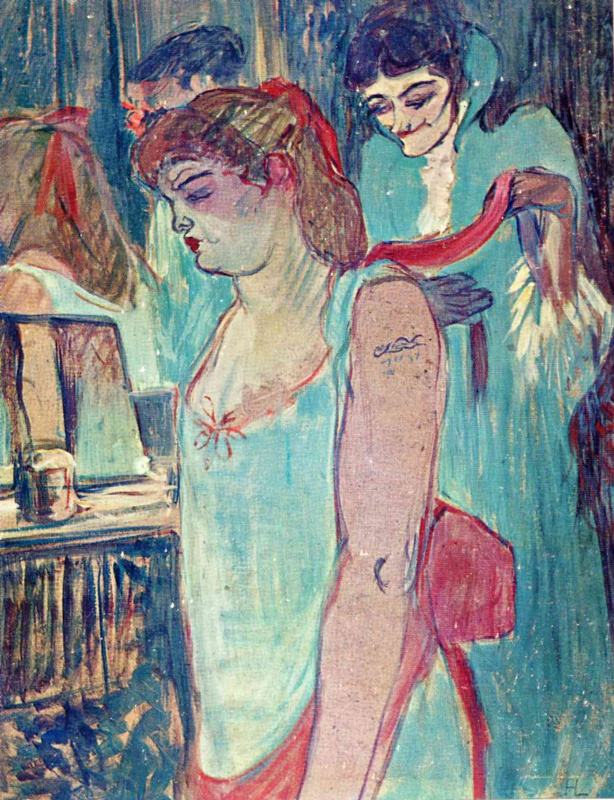

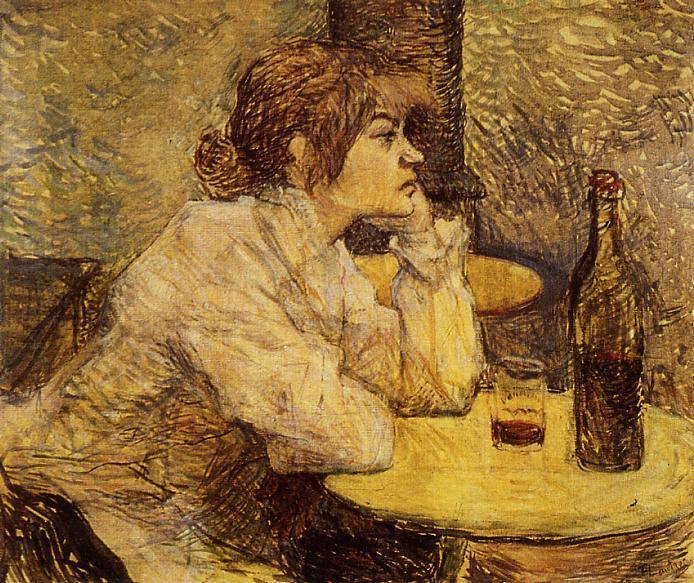

At the age of 17, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec came to Paris and settled in the Montmartre area, which the artist loved with with all his heart and which eventually broke his heart. The area ofcabarets and drunkards, courtesans and dancers, artists and homeless people became dear and beloved for the young count, he completely immersed himself in the bright and crazy life of Montmartre. Today, seeing penny souvenirs, powder boxes and postcards with recognizable silhouettes of Moulin Rouge dancers on the stalls of street vendors in Paris, a rare tourist thinks that the face of Belle Époque, the face of Paris of that time was created by Toulouse-Lautrec.The pioneer of posters

Moulin Rouge, one of the symbols of Paris, became what it became largely thanks to the hand of the young artist. In 1889, when the cabaret was just opening, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to create posters for this event. He created bold, in many ways scandalous and recognizable posters, which, posted throughout Paris, became a local sensation and attracted attention both to the artist himself and to the dancer depicted, the inventor of the cancan, La Goulue.Inspired by Japan

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec is usually referred to as a post-impressionist. He studied under the classics of academic painting Fernand Cormon and Léon Bonn, but later became interested in Paul Cézanne and Edgar Degas, who reworked the ideas of impressionism. The Japanese art of ukiyo-e engraving, literally, "pictures of the floating world", was also of great importance for the artist. Frequent subjects of ukiyo-e were theatrical scenes, recreation and leisure in Japan — these themes were close and understandable to Toulouse-Lautrec. The simplicity of form, clear contours, bright colours and picturesque flatness of Japanese prints are easily guessed in the posters by Toulouse-Lautrec, striving for laconic means, while evoking the maximum emotional response from the viewer.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec in the costume of the Japanese emperor. 1892. Photo by Maurice Guibert. The Source

This enthusiasm was so great that Toulouse-Lautrec was even photographed in the costume of the Japanese emperor, however, for some reason, with a macabre doll resembling a dead baby.

The face of Montmartre

Note that the image of the Japanese emperor was not the only case when the artist disguised himself as someone else. Prone to grotesque and irony, Toulouse-Lautrec loved to laugh at himself, choosing to be funny rather than pathetic. He gladly changed into an elderly lady in a strict dress and an elegant hat or a sad Pierrot, and sometimes into a little boy.Shame of the noble family

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec was adored by his many friends and mistresses from Montmartre for his sense of humour, talent, compassion, generosity and inexhaustible desire to continue to revel day and night. However, his growing popularity as an artist displeased his aristocratic parents — their son was becoming famous for his portraits of courtesans and cabaret dancers!Coffee Pot

Toulouse-Lautrec had an excellent sense of humour, as his friends believed (whereas more educated gentlemen found his jokes monstrously vulgar). With his characteristic irony, the young count found a charming metaphor for his short-legged body — he called himself "a small coffee pot with a big spout". The fact is that, as if apologizing for the imperfection of the lower extremities, nature extremely generously endowed the artist with his manhood. This feature, coupled with tenderness, courtesy and a complete lack of bias, made him an incredibly popular lover among the women of Montmartre, who, in turn, told their friends about the love exploits of Toulouse-Lautrec. Friends and mistresses quickly picked up the funny nickname, the artist himself loved to paint still lifes with coffee pots, and we can only guess to what extent these are still lifes, and to what extent they are a kind of self-portraits.

The author of a cocktail and passionate culinary specialist

In the chaotic days and nights of Montmartre, Toulouse-Lautrec found time not only for painting and revelry, but also for the art of cooking. He grew up in the rich and sophisticated world of the aristocracy, he knew a lot about gourmet food and deceptively light cocktails, completely knocking down the unassuming inhabitants of Montmartre. Without any financial problems as the heir of a very wealthy family, Toulouse-Lautrec ordered huge quantities of delicacies for his friendly feasts, and sometimes even asked his mother to send him a couple of barrels of good wine from the family cellars and game from his own lands.But the most famous is the Earthquake destructive cocktail by Toulouse-Lautrec, consisting of one part of absinthe and one part of cognac. One can imagine the effect it had at the artist’s noisy soirées!

Édouard Vuillard. One of the works for Alexander Natanson

"Alexandre Nathanson gave a grand reception at his home at 60 avenue Bois-de-Boulogne to show ten magnificent panels painted with glue paints with which Vuillard adorned the walls of his house. Lautrec suggested this reception. He made lithographic invitations in English written in large letters saying that "American and other drinks" would be served at the reception… The Nathansons' guests (there were three hundred of them) were surprised to see that Lautrec was acting as a bartender. On this occasion, he shaved the top of his head, removed his beard, leaving only two small tufts of hair, and put on a vest made of the Stars and Stripes American flag under the short white linen jacket. (…)

Throughout the night, he fiddled tirelessly behind the counter full of glasses, bottles, ice buckets, plates of lemons, sandwiches, salted almonds and potato straws. Lautrec whipped up cocktails, invented new mixtures, one more deadly than the other, determined to "knock down" the entire fashionable society. He wanted to make these respectable representatives of the literary and artistic world so much drunk that all their respect would flee from them, he wanted to undermine the authorities, to rip off the masks.

And he achieved his goal. (…) Almost no one was spared by the cocktails with ginger, the "love cocktail" and the "meadow oysters" by the bartender Lautrec, and to make his victims thirsty, he served them sardines on a silver platter with a burning sauce of port wine and juniper liqueur.

The most careless ones snored very soon on the sofas and beds in the rooms where they had been transferred…"

Henri Perruchot. La Vie de Toulouse-Lautrec

Friend and protector of Oscar Wilde

Toulouse-Lautrec made friends with the famous British writer and poet Oscar Wilde in Paris and painted him several times. In 1895, Wilde was found guilty of "rude and indecent behaviour" and sentenced to two years of hard labour. Toulouse-Lautrec appeared to have attended his trial during his visit to London, and he supported his friend — both personally and publicly. Paul Adam, who was a journalist for La Revue Blanche, published an article titled Vile Onslaught in which he passionately defended the Briton tormented by puritan British justice. Toulouse-Lautrec provided a pen and ink drawing of Wilde’s elegant silhouette to illustrate the article. He portrayed Wilde as a dandy, standing with his head held high.Lautrec on the big screen

An amazing personality, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec always arouses the interest of the viewer. The image of the artist is found in many films, some of these paintings have become true classics of cinema. Toulouse-Lautrec was played by José Ferrer in John Houston’s Moulin Rouge, John Leguizamo in the iconic Moulin Rouge! by Baz Luhrmann, Vincent Menjou Cortez in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.