When we say Sandro Botticelli, we recall images of beautiful women: the goddess of love, who appears from the sea on a giant shell (The Birth of Venus) or three graces in airy dresses, involved in a round dance in (Primavera). Botticelli was best known for such idealized portrayals of women. However, the work of the Renaissance

artist was not really limited to these magnificent erotic images — there also were violence, brutal murders and incitement to war.

First of all, we are talking about the series of four panels La Novella di Nastagio degli Onesti. The second picture is called The Punishment of Guido degli Anastagi and his Beloved (c. 1483) — this is perhaps the cruellest work in the cycle. It shows a knight in a pink-red cloak who had chased a naked woman in a forest. He stabbed her with a dagger in her back, plunged the fingers of his left hand deep into the bloody wound, took out her heart and threw it to the dogs. The main subject, Nastagio, watches this scene with horror.

A scene from "La Novella di Nastagio degli Onesti" series. II

1483, 82×138 cm

The art critic Gabriel Montois calls this panel "one of the cruellest (!) images of torture against women in classical painting". And it is unlikely that this work can be considered an obsolete warning against male assault — today’s women are still afraid of cruel tricks by rejected admirers. With such a visual representation of brutality against women, Botticelli exacerbated the viewer’s shock, intended to serve certain social and political goals.

The primary source for La Novella di Nastagio is the story from Boccaccio’s Decameron. The protagonist of this story, a nobleman Nastagio, was rejected by the daughter of Paolo Traversari — a woman he wanted to marry. He left his native Ravenna and wandered through the forest in sad meditation. The young man’s thoughts were interrupted by the appearance of a naked girl running from a horseman and his dogs striving to bite her.

The primary source for La Novella di Nastagio is the story from Boccaccio’s Decameron. The protagonist of this story, a nobleman Nastagio, was rejected by the daughter of Paolo Traversari — a woman he wanted to marry. He left his native Ravenna and wandered through the forest in sad meditation. The young man’s thoughts were interrupted by the appearance of a naked girl running from a horseman and his dogs striving to bite her.

A scene from "La Novella di Nastagio degli Onesti" series. I

1483, 83×138 cm

Nastagio learned that the couple’s story was similar to his own. In fact, he sees two ghosts subjected to divine punishment. When alive, the horseman used to be his great-grandfather Guido degli Anastagi, who had committed suicide after his beloved rejected him. Now they both were to expiate their sins: every Friday they experienced the scene of persecution in the forest. Nastagio ran away, and various episodes of the chase repeated behind his back.

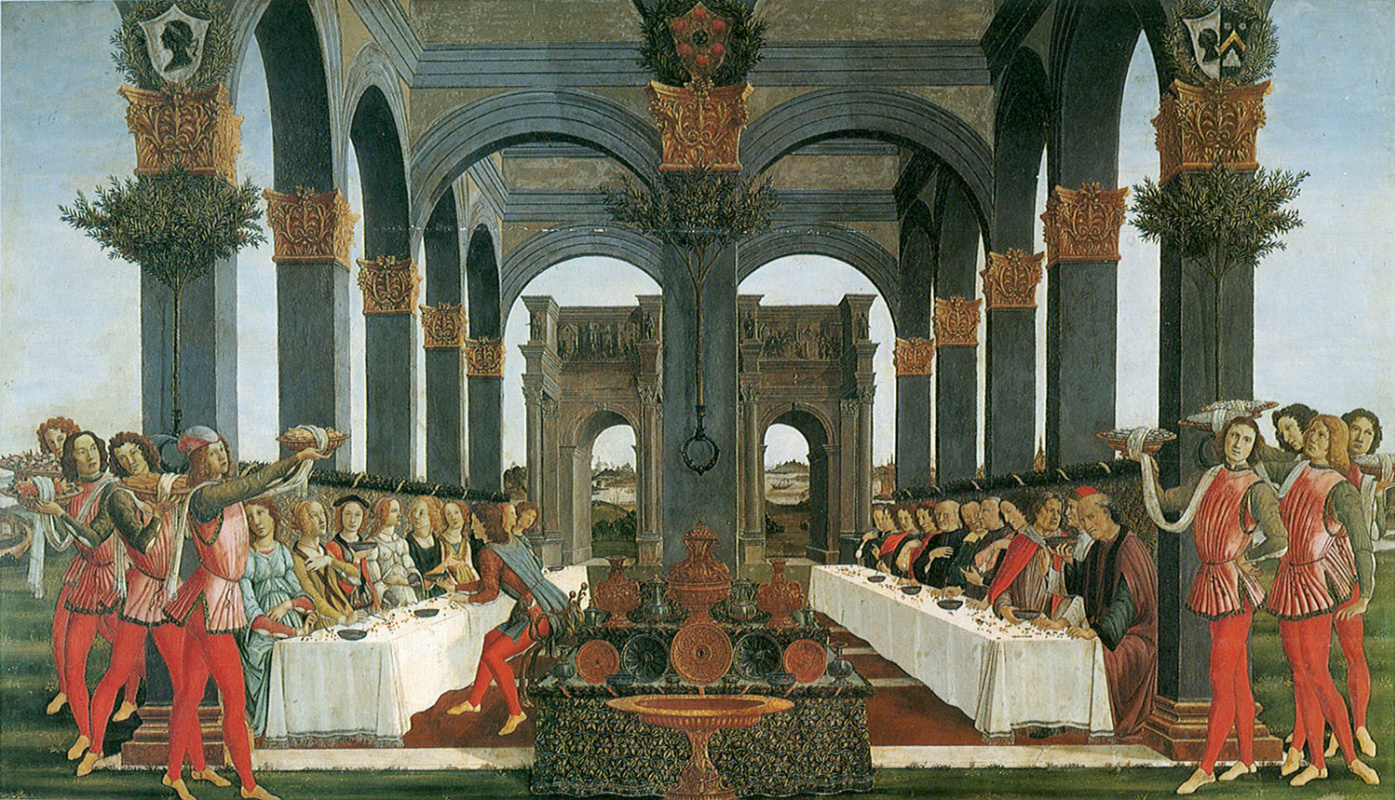

After this, Nastagio had the idea to invite the Traversari family the following Friday to watch this scene. On the third panel, Botticelli portrayed this episode as an interrupted picnic. At tables covered with white cloths, stunned guests see the knight stab the woman who rejected him and throw her heart to dogs. Traversari daughter, afraid that the same fate awaited her, agreed to marry Nastagio. The fourth panel shows the wedding feast in honour of the couple.

After this, Nastagio had the idea to invite the Traversari family the following Friday to watch this scene. On the third panel, Botticelli portrayed this episode as an interrupted picnic. At tables covered with white cloths, stunned guests see the knight stab the woman who rejected him and throw her heart to dogs. Traversari daughter, afraid that the same fate awaited her, agreed to marry Nastagio. The fourth panel shows the wedding feast in honour of the couple.

A scene from "La Novella di Nastagio degli Onesti" series. III

1483, 84×142 cm

The art critic Scott Nethersole wrote that this transition from violence to celebration demonstrates a "thematic development" from cruelty to a "civilizational model of urban culture in which peace and harmony are brought with marriage". At the same time, the scientist leaves out that an alliance with a woman driven by fear is unlikely to lead to peace and harmony — at least for her. More likely — and it’s more important — for wealthy Italians of the Renaissance

society, marriage could lead to economic and political harmony between the two families.

A scene from "La Novella di Nastagio degli Onesti" series. IV

1483, 83×142 cm

"Botticelli understood very well how to present violence and how to influence the viewer," explains Nethersole. In other words, the artist knew that his cruel paintings could force women to take a submissive role in her family. Nethersole contrasts the La Novella di Nastagio panel with another tough work by Botticelli, The Story of Lucretia (c. 1500). These paintings were trellises or painted wall panels, which were intended to decorate the homes of wealthy families and are now regarded as daily reminders of morality. The women with long blonde hair depicted in each work are strikingly similar to the beauties from the most famous Botticelli’s works. On the mentioned trellises, the heroines appear as rather the embodiment of all women, and not as separate individuals.

Unlike the Nastagio series, The Story of Lucretia is a narrative in one horizontal panel. The symmetry of the composition illustrates another ideal of Renaissance — order and balance. In the centre of the picture, there is a classic triumphal arch, surrounded by two corner buildings with columns. In the foreground, a crowd of people in armour brandish their swords, mourning for the lifeless figure in the centre, Lucretia in a green robe lying in a black coffin with a dagger in her chest.

The Story Of Lucretia

1501, 83×180 cm

The source of the legend is unknown, while its most famous documentary was the ancient Roman historian Livius. According to the legend, the Roman matron Lucretia was raped by the royal son Sextus Tarquinius. Because of the shame, she stabbed herself, despite the fact that neither her father nor her husband blamed her or considered her defiled. The enraged uncle of Lucretia, Brutus, declared war on Tarquinius, won and established a republic in Rome instead of a monarchy.

In The Story of Lucretia, the cause for action was not violence, but its consequences. In the picture by Botticelli, soldiers are enraged only when they see the body of the dead matron. The Lucretia’s death is not only a tragedy, it also becomes a political tool. Despite the fact that the legend of Lucretia is mostly about feminine purity and fidelity, the artist has introduced an unforgivable amount of propaganda into his panel. The long straight swords of the soldiers and the tall column in the centre of the picture serve as symbols of the phallic power that connects the struggle of the story heroes with the structures that literally held the organization of Florence of the day. That is, customers who hung this trellis in their home received a daily reminder of the Republican ideals.

In The Story of Lucretia, the cause for action was not violence, but its consequences. In the picture by Botticelli, soldiers are enraged only when they see the body of the dead matron. The Lucretia’s death is not only a tragedy, it also becomes a political tool. Despite the fact that the legend of Lucretia is mostly about feminine purity and fidelity, the artist has introduced an unforgivable amount of propaganda into his panel. The long straight swords of the soldiers and the tall column in the centre of the picture serve as symbols of the phallic power that connects the struggle of the story heroes with the structures that literally held the organization of Florence of the day. That is, customers who hung this trellis in their home received a daily reminder of the Republican ideals.

Sandro Botticelli, The Story of Lucretia (detail)

Botticelli captures the moment of aggression in La Novella di Nastagio, whereas in The Story of Lucretia he demonstrates what happened immediately after the violence — the subject’s suicide and the battle that provoked it. This difference means that each painting carries an alternative moral lesson. Observing violence is crucial in the story of Nastaggio, because it serves as a warning to women, while evidence of the destructive potential of the same violence is an integral part of the nationalist impulse in the story of Lucretia.

"Boccaccio made it clear that violence has several consequences," Nethersole writes. "It causes fear and stimulates compassion. It can also catalyse changes in soul and behaviour." As Niccolò Machiavelli later claimed in his treatise The Prince, it is better to instill fear than love. The cruel images by Botticelli also suggest that it was more important for him to inspire fear in the viewer, rather than seduce him. Today, the artist’s messages seem completely depressing — but, unfortunately, still relevant. In the days of Botticelli, just as nowadays, the safety of the female body is secondary to political expediency.

"Boccaccio made it clear that violence has several consequences," Nethersole writes. "It causes fear and stimulates compassion. It can also catalyse changes in soul and behaviour." As Niccolò Machiavelli later claimed in his treatise The Prince, it is better to instill fear than love. The cruel images by Botticelli also suggest that it was more important for him to inspire fear in the viewer, rather than seduce him. Today, the artist’s messages seem completely depressing — but, unfortunately, still relevant. In the days of Botticelli, just as nowadays, the safety of the female body is secondary to political expediency.

Based on Artsy.net