They were one of the most influential couples in American art history of the 20th century. Their marriage lasted seven decades and can be considered a model of married life. However, there were moments in the relationship between Andrew and Betsy Wyeth that remained a mystery to their contemporaries.

Maga’s Daughter

"…It's my wife, Betsy. I had worked a long time on this [painting] and knew it wasn’t working. At the time I was on board of trustees of the Smithsonian Institution — quite prestigious. But Betsy didn’t like it, telling me that my work would suffer because of all these boards. I left for Washington one morning, and Betsy got furious, really flew into a rage. All the way down I kept thinking of that colour rising up high into her cheeks. I knew I had captured her. The colour of those cheeks under her coal black hair and that hat gives the portrait a real edge. […] It’s more than a picture of a lovely looking woman. It’s blood rushing up."

Maga’s Daughter

1966, 54×67.3 cm

This is how the artist Andrew Wyeth wrote about his portrait "Maga's Daughter", that was created in 1966. He depicted his beloved wife in a three-quarter view, standing erect. Her bearing is one of dignified pride as she averts her eyes away from the viewer. Atop her head is an antique riding hat with its drawstrings dangling freely on either side of her face, almost if they were acting as a frame of a picture. She wears a drab-coloured, high collared dress which almost blends in with the slightly lighter coloured background. There is a faint flush of colour to her cheeks and a smile is forming on her lips. Her beautiful eyes are lit by the unseen light source to the left of the painting.

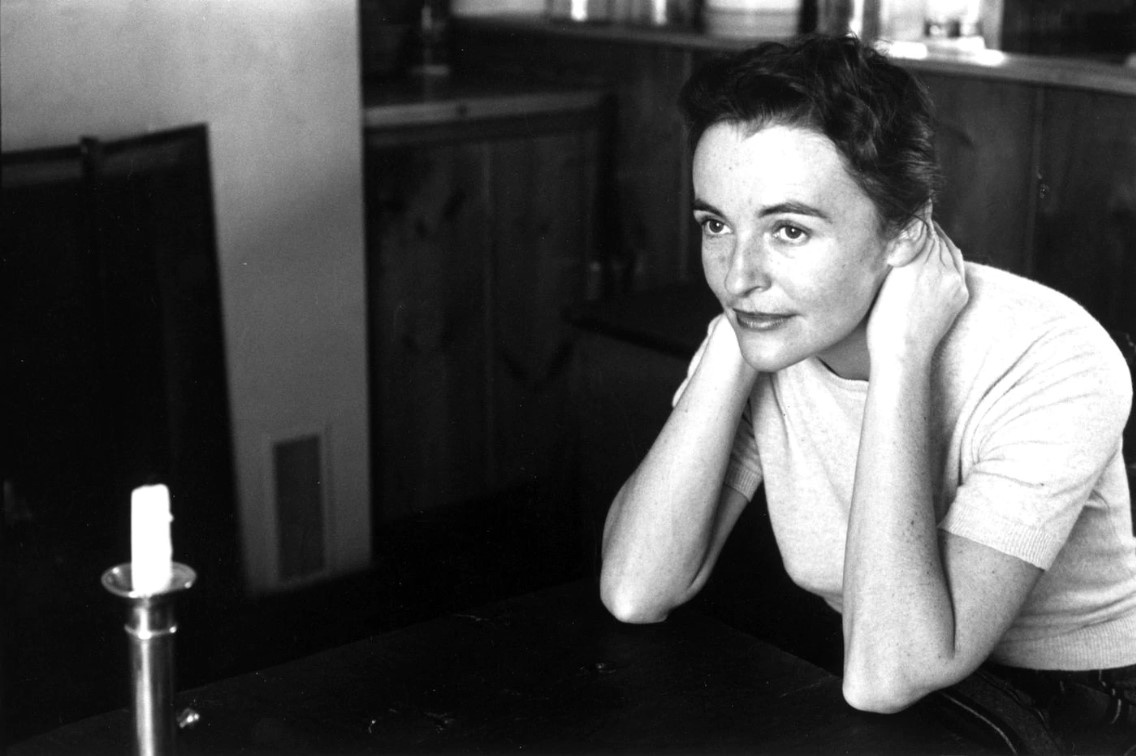

Betsy Wyeth has been an associate, business manager and muse for her husband Andrew for seven decades, as well as the chief archivist of his work. She introduced her husband to the subject of his most famous painting "Christina's World" (1948), posed for the woman crawling across the field to the house, and gave the work its name. It is unlikely that Andrew Wyeth would have achieved his position and fame if he had not once met Betsy Merle James, daughter of Elizabeth "Maga" James (hence the title of the "Maga's Daughter" portrait).

Betsy Wyeth has been an associate, business manager and muse for her husband Andrew for seven decades, as well as the chief archivist of his work. She introduced her husband to the subject of his most famous painting "Christina's World" (1948), posed for the woman crawling across the field to the house, and gave the work its name. It is unlikely that Andrew Wyeth would have achieved his position and fame if he had not once met Betsy Merle James, daughter of Elizabeth "Maga" James (hence the title of the "Maga's Daughter" portrait).

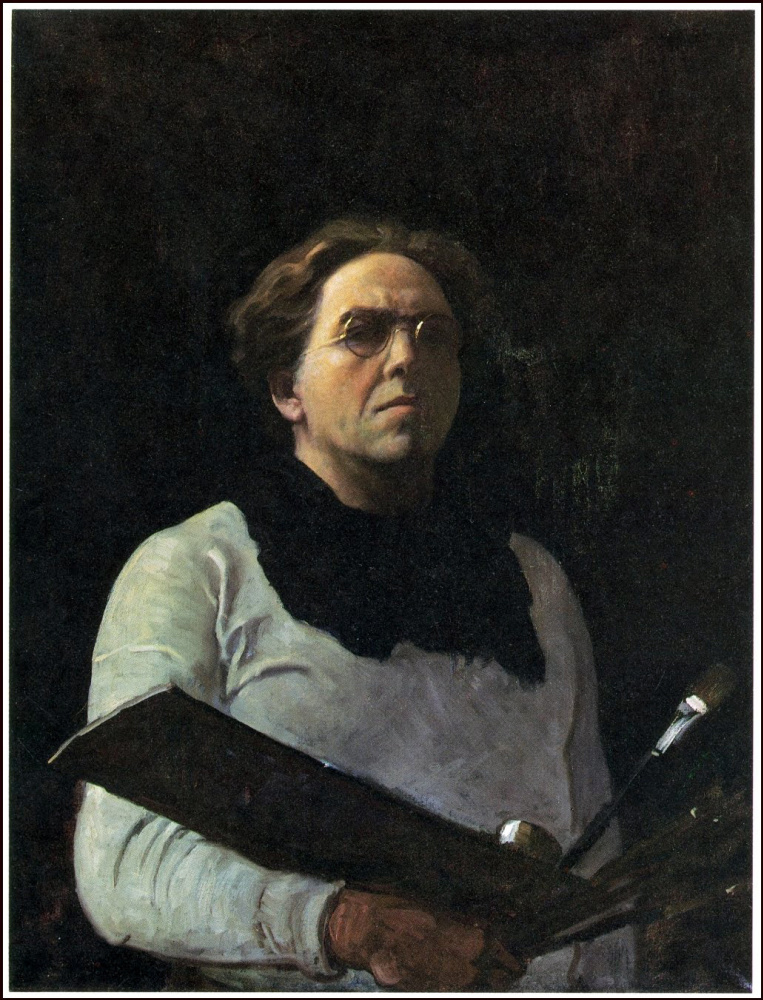

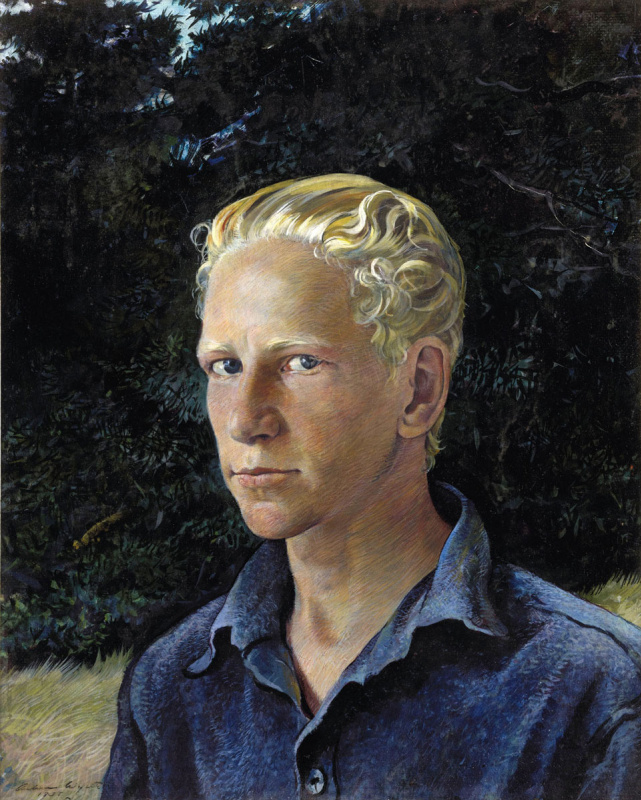

Newell’s son

Andrew Wyeth was born in 1917 in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. His father was Newell Converse (N.C.) Wyeth, one of America’s greatest illustrators. Andrew was the youngest child in the family, and his three sisters and brother were also brilliant. The eldest sister, Henrietta, is often referred to as one of the most important female artists of the 20th century. The second daughter, Caroline, also followed her father’s footsteps, and the youngest Ann became a gifted musician. Nathaniel, Andrew’s older brother, was a mechanical engineer and inventor.As an illustrator, Newell Converse Wyeth made a decent living, and the family was well off. Andrew was not in good health, one illness followed another, and he had to spend a lot of time at home, taking drawing lessons from his father. There was a noticeable difference between them: Wyeth Sr. was a large man with an unlimited supply of energy, in stark contrast to his weak and fragile son. Wyeth recalled of that time: "Pa kept me almost in a jail, just kept me to himself in my own world, and he wouldn’t let anyone in on it. I was almost made to stay in Robin Hood’s Sherwood Forest with Maid Marion and the rebels."

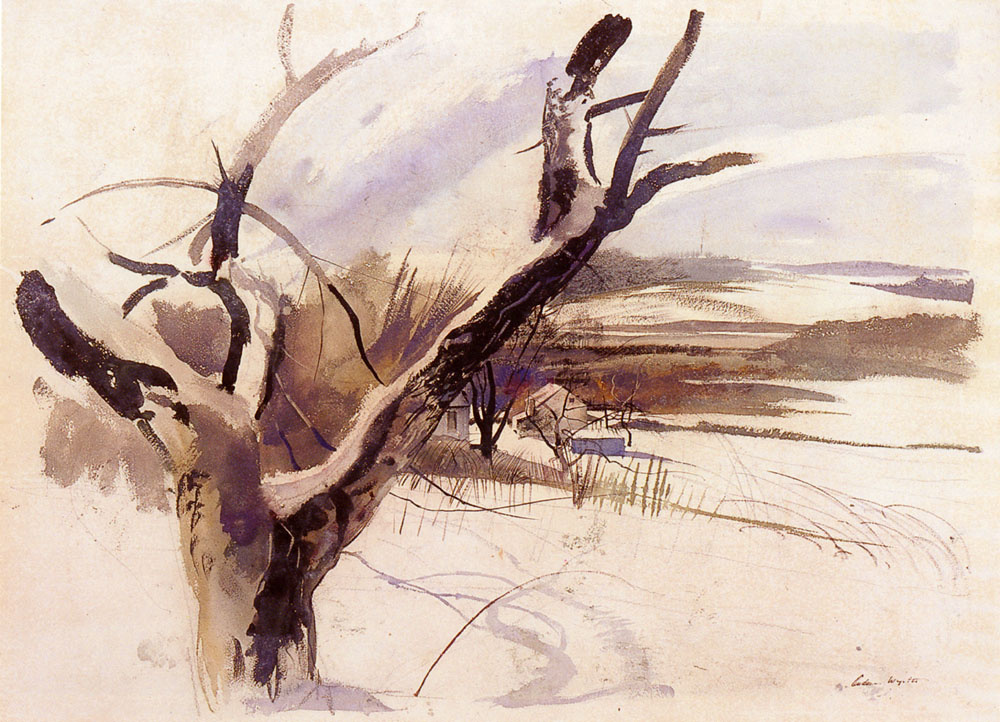

N.C. Wyeth became famous for drawing for the famous Treasure Island by Robert Lewis Stevenson, even before Andrew was a teenager. Other famous novels followed, such as The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper and Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe. Under the guidance of his father, Andrew mastered watercolour

, was inspired by rural landscapes and absorbed the artistic traditions of the Wyeth family. Soon, the young man became interested in the history of art and was fond not only of the work of the Renaissance

artists, but also of American artists such as Winslow Homer.

In 1937, at the age of 20, Andrew got his first solo watercolour exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York. It was a resounding success, and all the works presented were sold. Now Wyeth Jr. himself was convinced that an artistic career was his real dream. However, the early triumph did not calm him down, like many talented people. The young man was extremely self-critical and was irritated by some of his work believing it to be too facile.

In 1937, at the age of 20, Andrew got his first solo watercolour exhibition at the Macbeth Gallery in New York. It was a resounding success, and all the works presented were sold. Now Wyeth Jr. himself was convinced that an artistic career was his real dream. However, the early triumph did not calm him down, like many talented people. The young man was extremely self-critical and was irritated by some of his work believing it to be too facile.

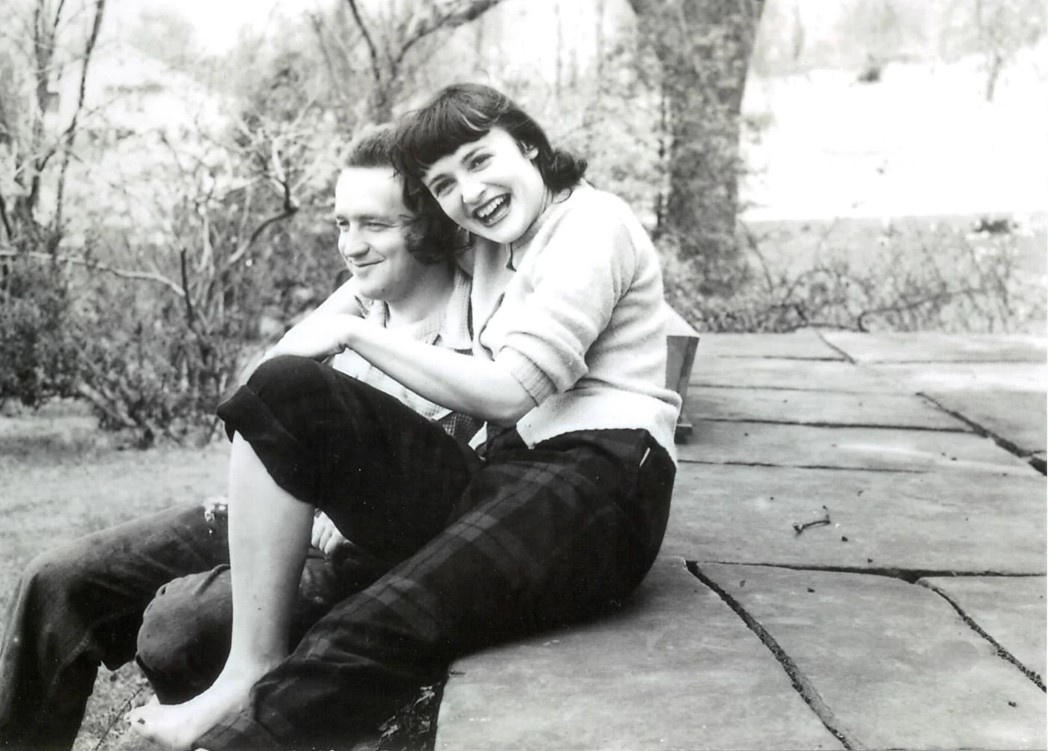

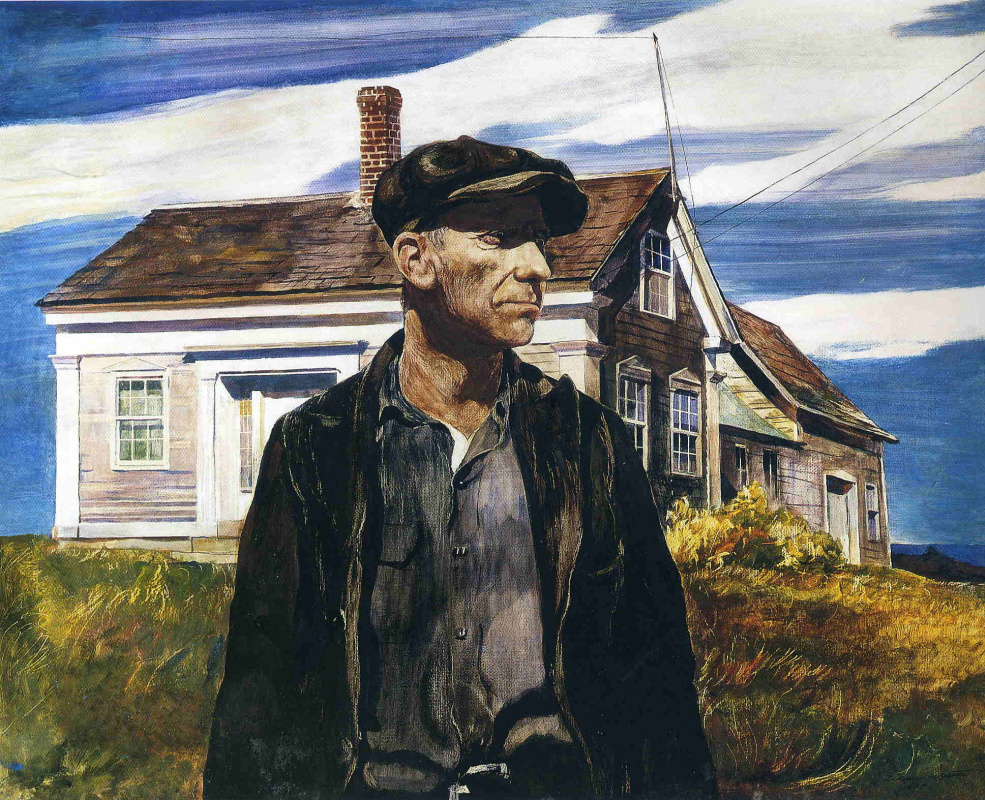

When Andrew met Betsy

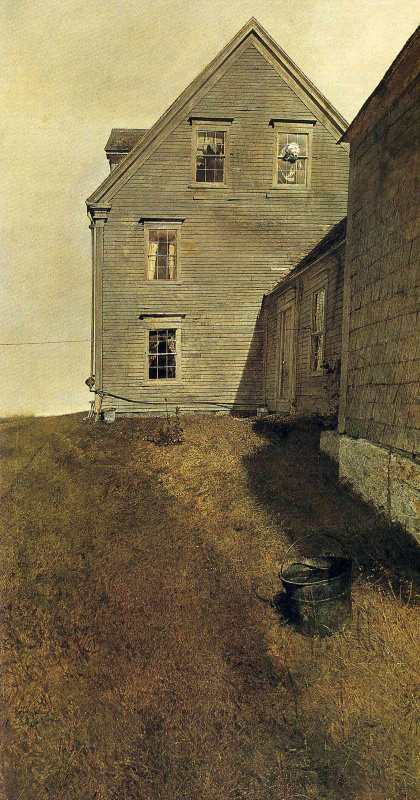

Andrew Wyeth met 17-year-old Betsy Merle James on 12 July 1939, the day he turned 22. The girl was the youngest of three daughters of artist Merle James, who worked for the Buffalo Courier Express. In the 1930s, the family spent the summer visiting friends at Bird Point, Maine. There they had neighbours: a blueberry farmer Alvaro Olson and his partially paralysed sister Christina, who suffered from polio as a child. Betsy was friends with Christina, and she took Andrew to her at their very first meeting.

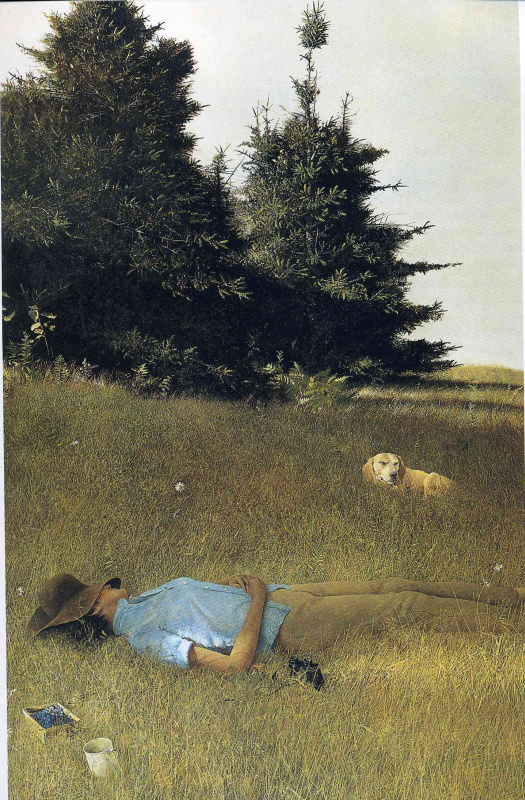

Christina's World

1948, 81.9×121.3 cm

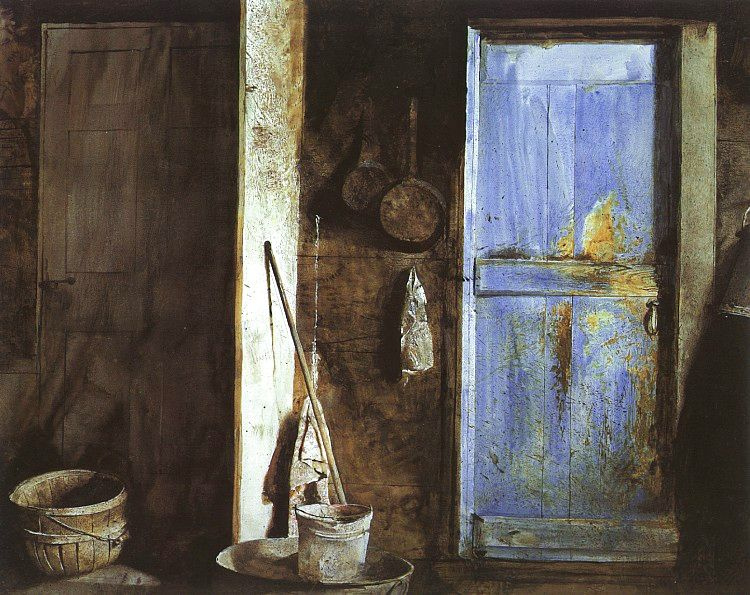

Strangely, at this first meeting, it was not Christina who made the greatest impression on Andrew Wyeth but the weather-beaten, three-story, steep-roofed, clapboard house, built on a coastal promontory which was her home. However later Christina and Andrew became good friends and she featured in many of his paintings including three beautiful portraits entitled, "Christina Olson" (1947), "Miss Olson" (1952), and "Anna Christina" (1967). Christina even allowed him to convert one of the rooms in their farmhouse into a studio.

Betsy was not an artist, but Andrew often asked her for her opinion on his work. On one of his first dates, he invited her to his studio and showed his watercolours. Betsy pointed to a tempera work lying on the floor, made in 1936 and later titled "The Young Swede", and said she would like to see more of these. And Wyeth mastered this technique. "If she hadn’t pushed him to work in tempera, he would never have become the artist he was," said Wyeth’s granddaughter Victoria.

Betsy was not an artist, but Andrew often asked her for her opinion on his work. On one of his first dates, he invited her to his studio and showed his watercolours. Betsy pointed to a tempera work lying on the floor, made in 1936 and later titled "The Young Swede", and said she would like to see more of these. And Wyeth mastered this technique. "If she hadn’t pushed him to work in tempera, he would never have become the artist he was," said Wyeth’s granddaughter Victoria.

A year after their first meeting, Andrew and Betsy were married and set up home in an old schoolhouse which lay on the Wyeth family land. Betsy had a strong character and exerted almost as much influence on her husband as his father. In the early days of her marriage, she believed that she had to battle with Andrew’s father to gain her husband’s attention. She once commented to Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth’s biographer, on her battle with her father-in-law: "I was part of a conspiracy to dethrone the king — the usurper of the throne. And I did. I put Andrew on the throne…"

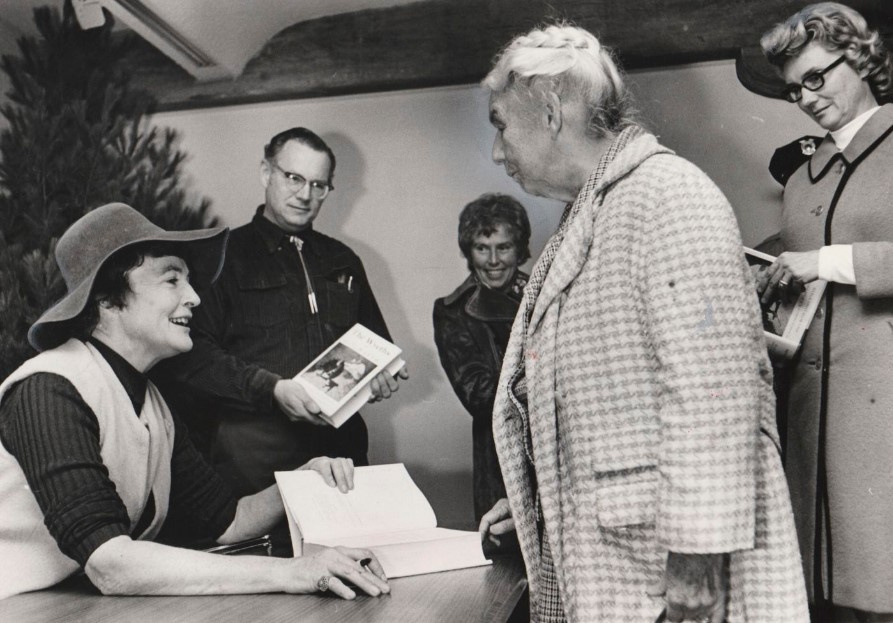

After the death of her father-in-law, Betsy compiled and edited her book The Letters of N. C. Wyeth, 1901−1945, which prompted art critics to reassess his career.

After the death of her father-in-law, Betsy compiled and edited her book The Letters of N. C. Wyeth, 1901−1945, which prompted art critics to reassess his career.

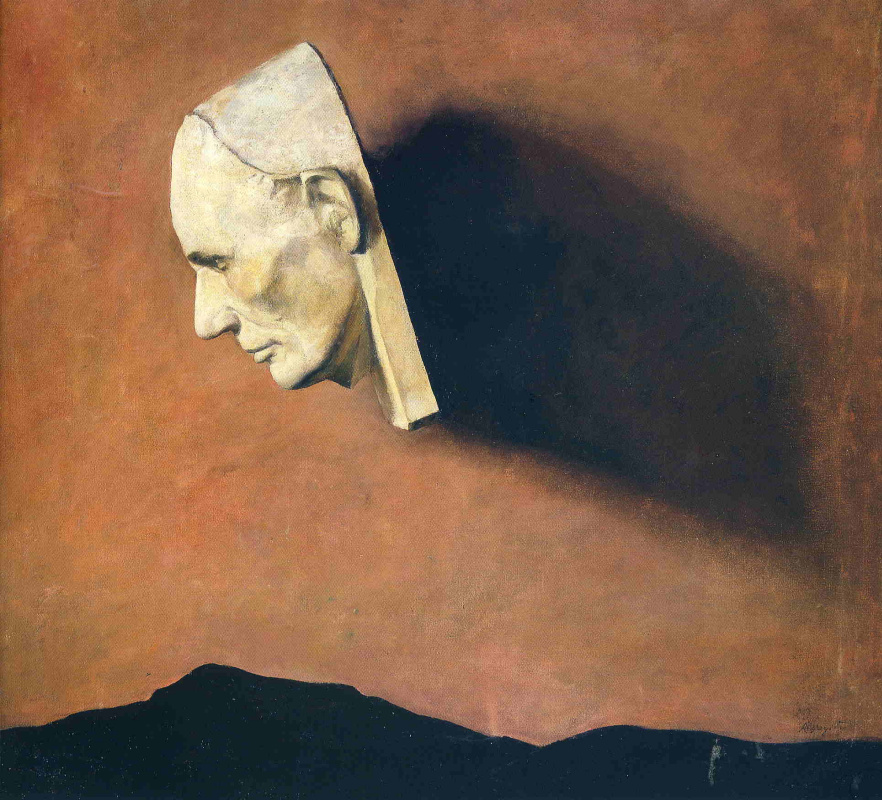

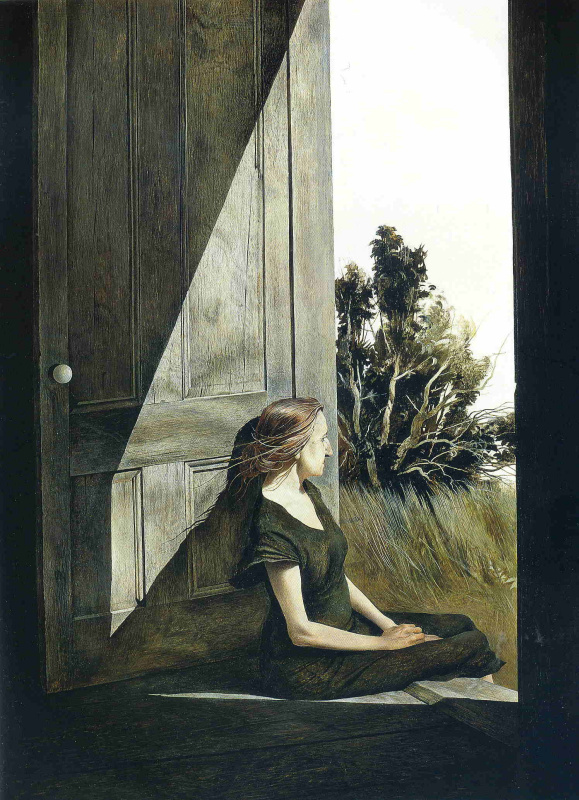

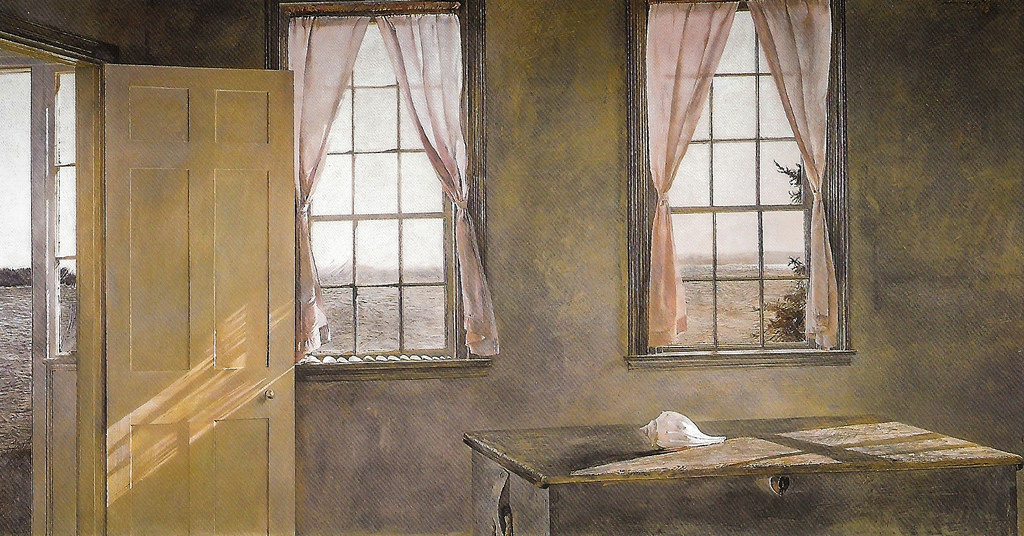

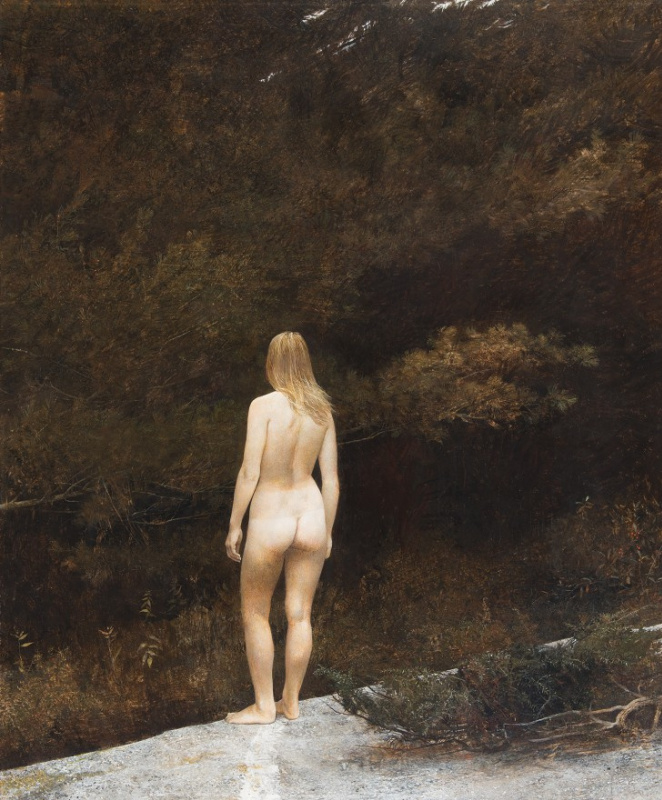

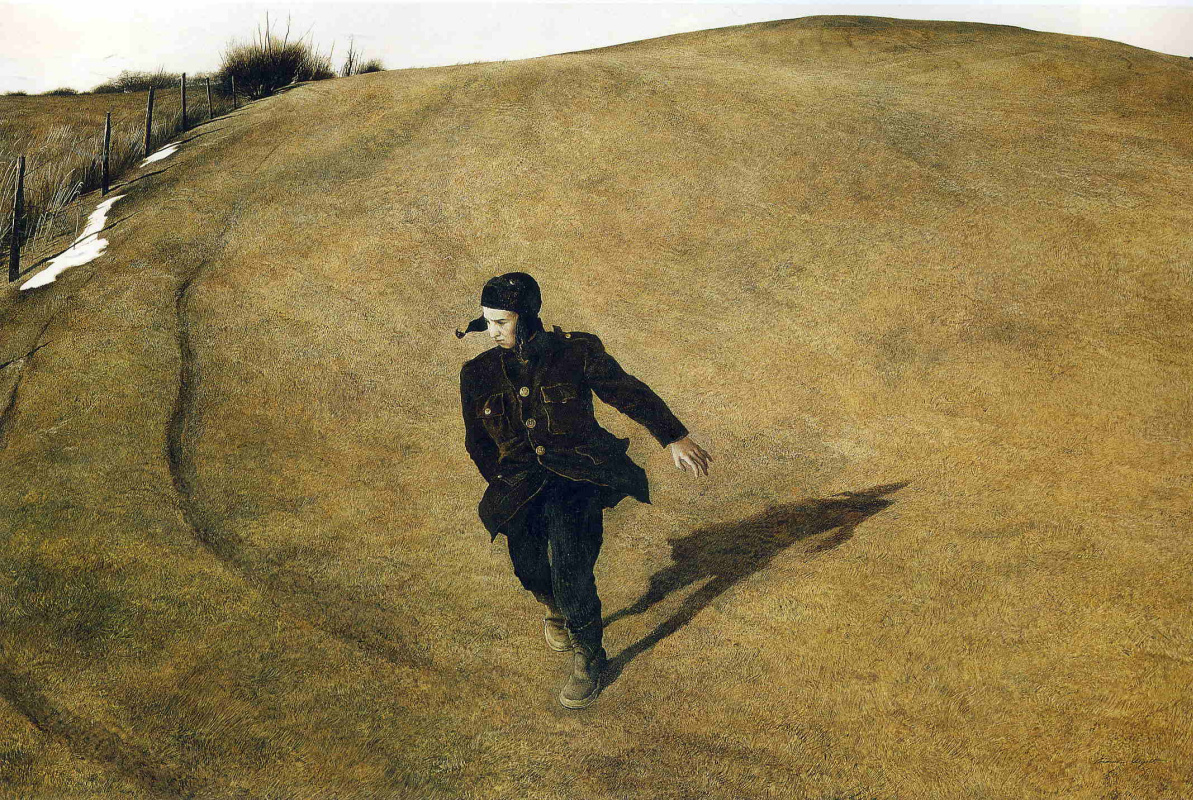

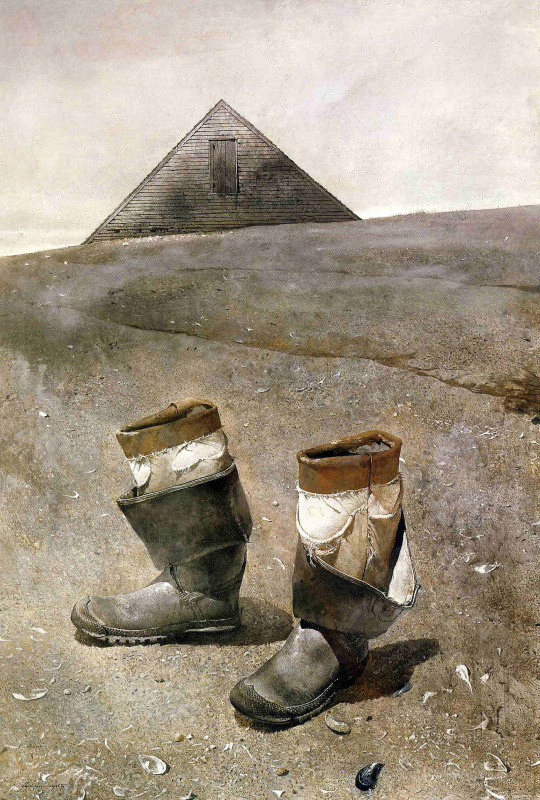

The flow

1982

In 1943 the couple had their first child, a son Nicholas. A second son, James followed three years later and would become a renowned artist in his own right. Eighteen years after the couple married, they bought an old 18th century gristmill on the banks of the Brandywine River in Pennsylvania. Betsy used her sharp mind and talent for design to restore the old mill, converting it into a home and a studio. She constantly turned to the Maine coast, where she and Andrew spent part of their childhood, and they bought three islands over the decades — Southern, Allen and Banner. For Betsy, they became a blank canvas where she was able to realize her creativity and passion for the preservation of historic New England architecture. Her carefully selected interiors are featured in many of Andrew Wyeth’s paintings and watercolours.

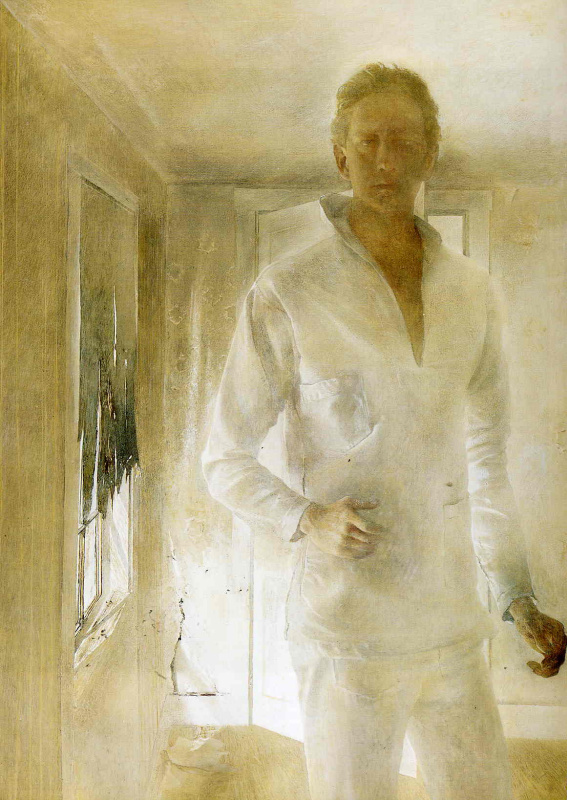

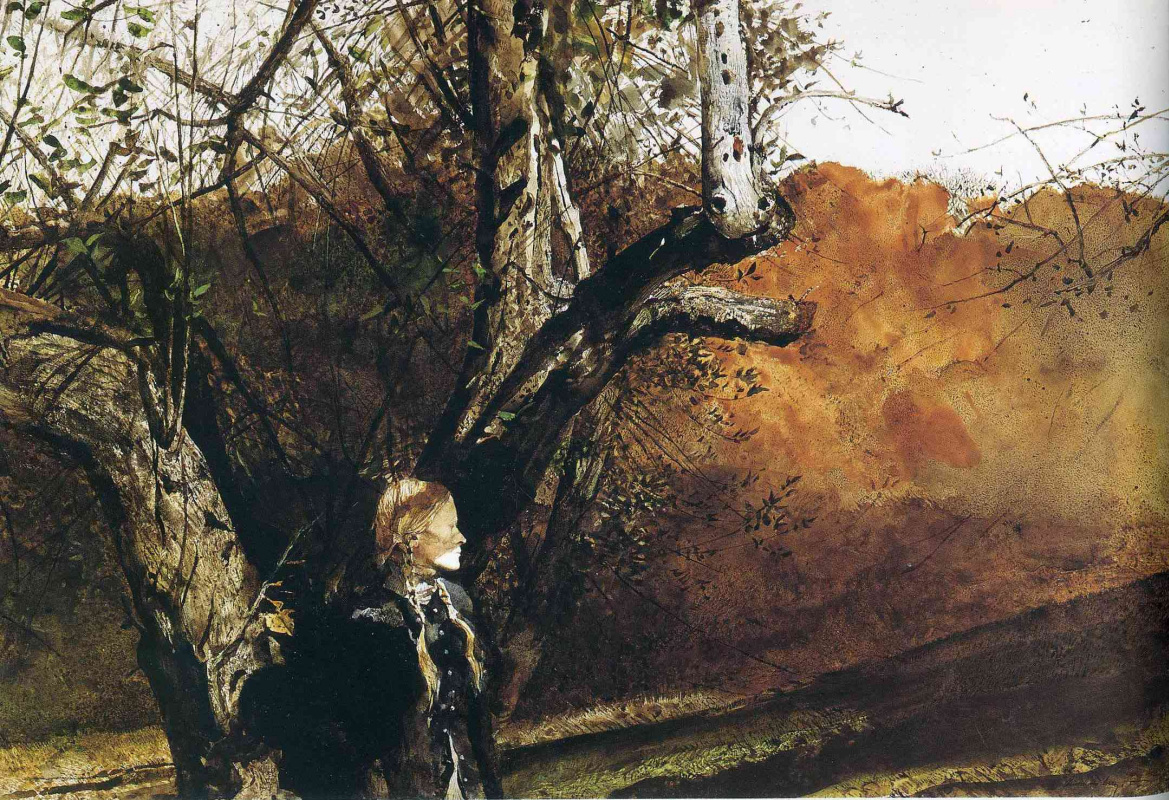

The Secret Helga

It is difficult to say what was the motivation behind Andrew Wyeth when he chose models for his paintings. Art critic Wanda Korn called him a metaphorical realist, implying that he preferred people who reminded him of certain aspects of life or fragments of history that he was interested in. Wyeth explained: "The difference between me and a lot of painters is that I have to have a personal contact with my models. … I have to become enamoured. Smitten. That’s what happened when I saw Helga."

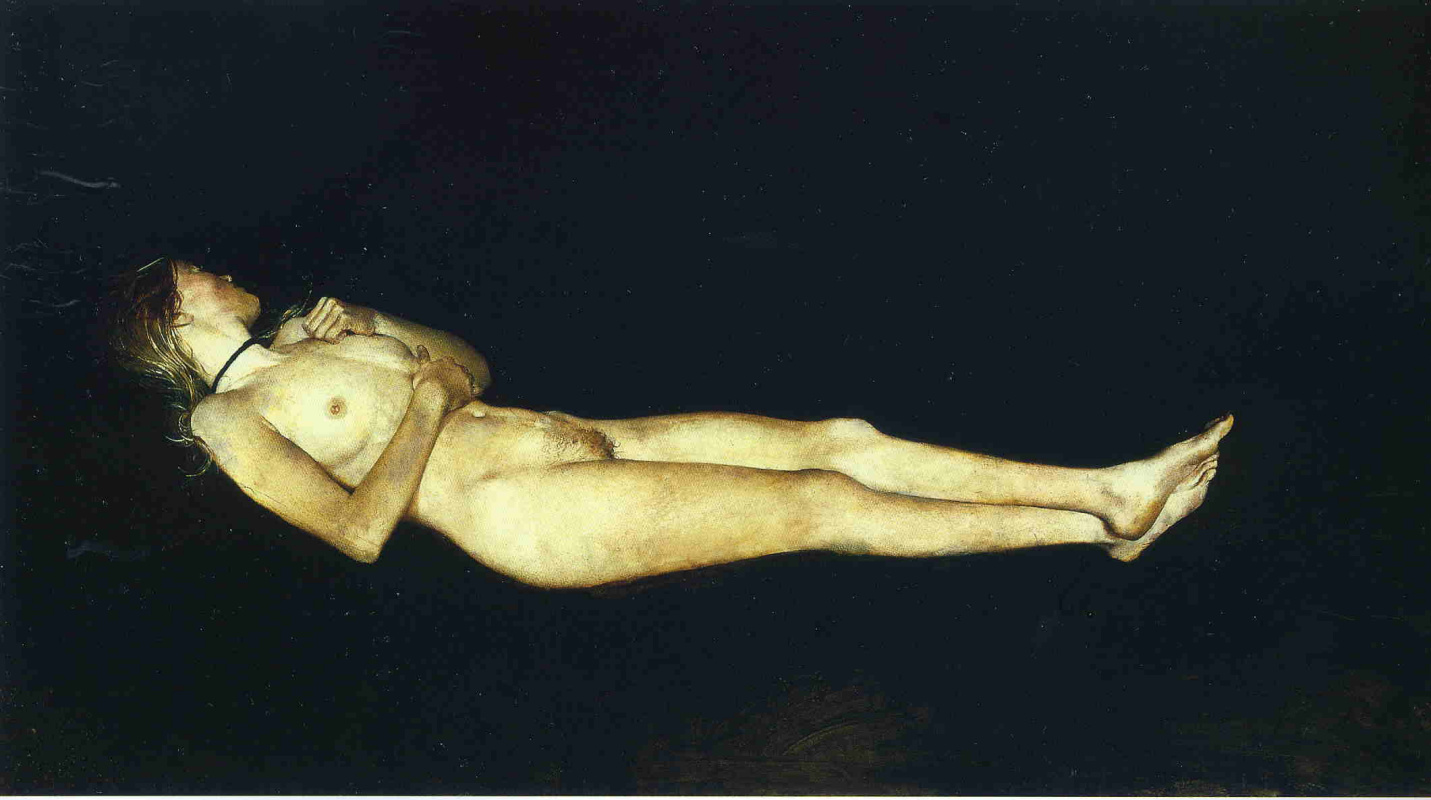

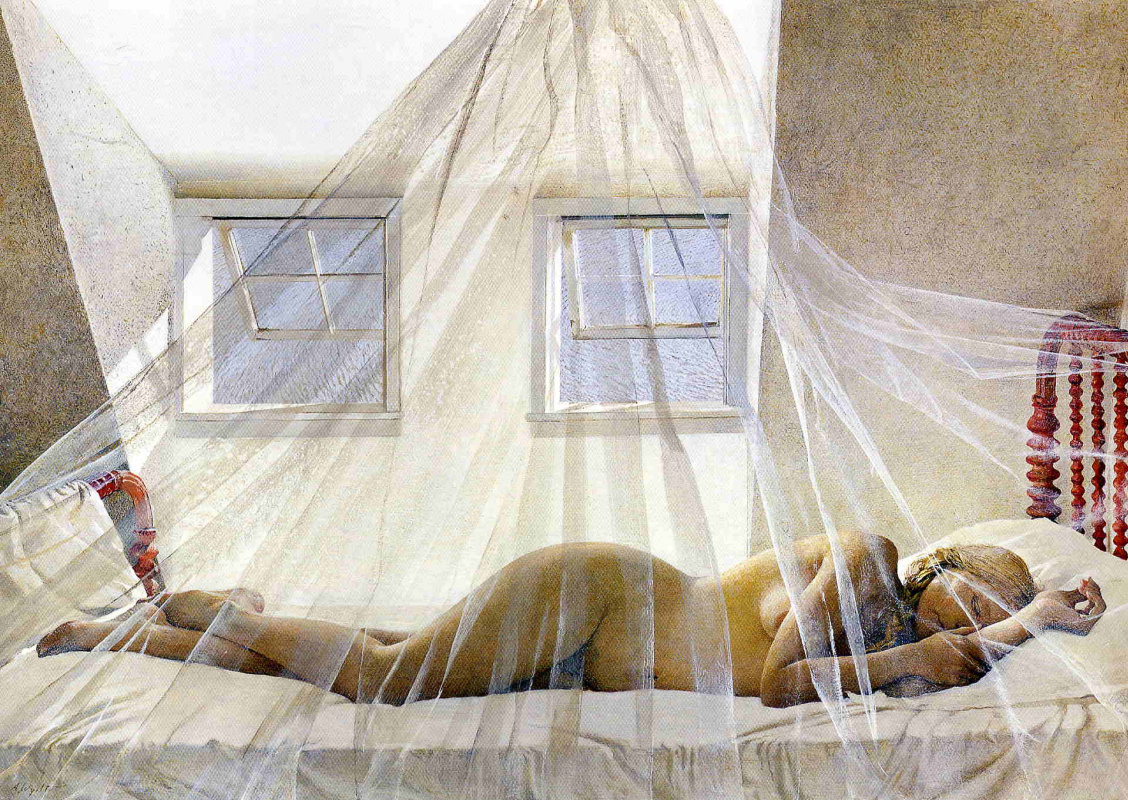

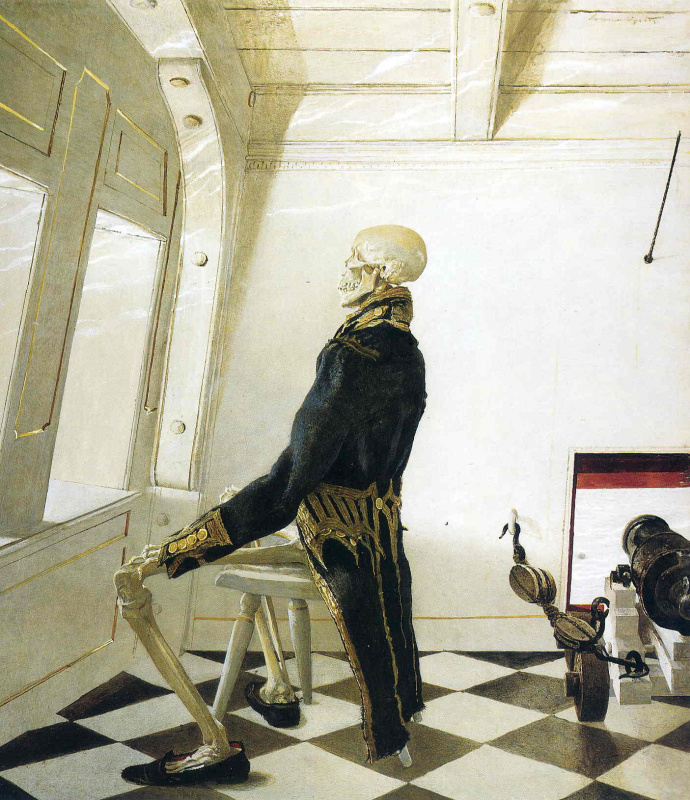

Lovers

1981

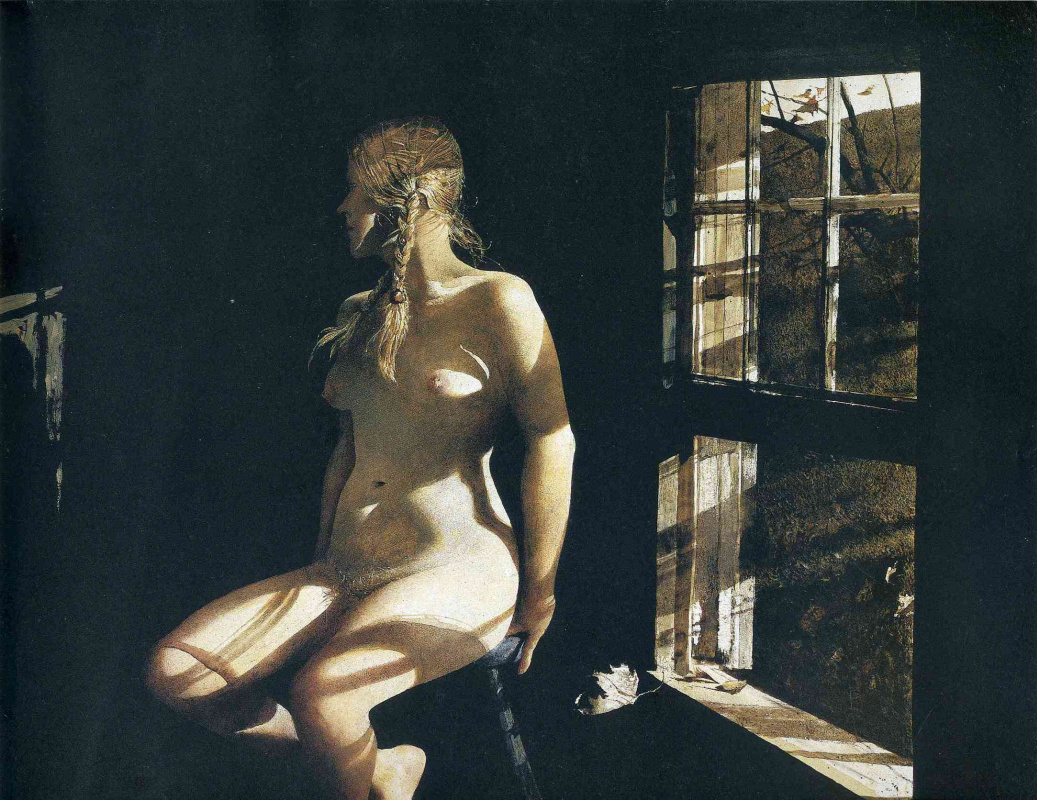

The artist met Helga Testorf when she was working as a nurse for Karl Körner, a neighbour whom Wyeth had been painting for decades. He invited her to pose for him in 1971, and over the next 14 years he painted 45 paintings and made 200 drawings, in which she appeared both dressed and naked. The sessions were a mystery even for their spouses, as were the artist’s artworks. Andrew Wyeth said that Helga attracted him with "all her German qualities, her strong, determined stride, that Loden coat, the braided blond hair".

In August 1986, the artworks were made public, and a real storm broke out in the art world. Betsy claimed to have learned about them a year before from her husband, who revealed the secret when he was afraid of dying of the flu. And when the journalists asked about the pictures, Mrs. Wyeth made a serious pause, and then uttered the magic word "love".

In August 1986, the artworks were made public, and a real storm broke out in the art world. Betsy claimed to have learned about them a year before from her husband, who revealed the secret when he was afraid of dying of the flu. And when the journalists asked about the pictures, Mrs. Wyeth made a serious pause, and then uttered the magic word "love".

Braids (from the series "Helga")

1979, 41.9×52.1 cm

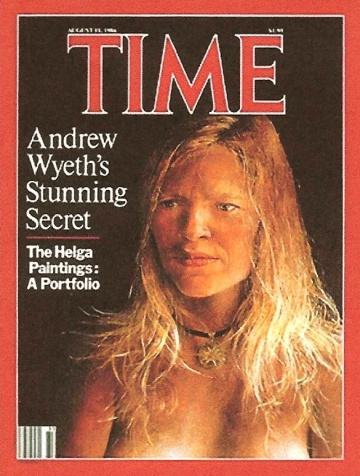

Two leading American media outlets, Time and Newsweek, decided to put the story of Andrew Wyeth and Helga Testorf on their covers. No other artist, including Picasso, has ever received such an honour. But the reporters sent to write the articles were disappointed. They spent a lot of effort looking for Helga, but when they found her, the newly minted American Mona Lisa refused to be interviewed. "I'm a Prussian, I’m not talking about secrets!" she declared and disappeared behind the backs of her angry husband, hostile children (the Testorfs had four of them) and a couple of dobermans.

Time magazine cover dedicated to the story of Andy Wyeth and Helga Testorf

No one has found any evidence that Wyeth and Helga ever had an affair. If the pictures were about Love, as Betsy vaguely hinted, then this love was too generalized. Moreover, later the suspicion was confirmed that the artist’s wife knew about Helga’s portraits and even owned some of them. As Andrew’s administrator, she could hardly have overlooked a quarter of a thousand works in a third of their life together. After the storm had settled, the new owner of the paintings with Helga gave Betsy some of them. It was Wyeth’s wife who named the one, considered the most famous in the series now, "The Lovers".

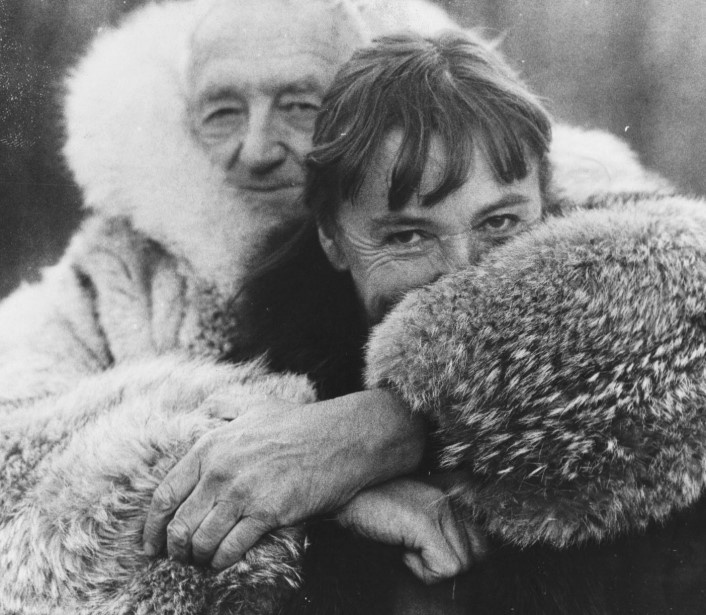

Helga remained with Wyeth until his death, serving as his nurse, masseuse and assistant. In 2007, when Wyeth was asked if Helga was going to be present at his 90th birthday party, he said "Yeah, certainly. She’s part of the family now. I know it shocks everyone. That’s what I love about it. It really shocks ‘em."

By bequest, Helga inherited the Newell Converse’s farmhouse in Maine, and she still grows blueberries and makes jam there.

By bequest, Helga inherited the Newell Converse’s farmhouse in Maine, and she still grows blueberries and makes jam there.

Her husband died in 2015, and the woman herself can often be seen in her "trademark" outfits of her favourite white and gold colours at the opening of exhibitions at the Brandywine River Museum of Art.

Victoria Wyeth, the artist’s granddaughter, and Helga Testorf at the opening of the exhibition (2017, photo source)

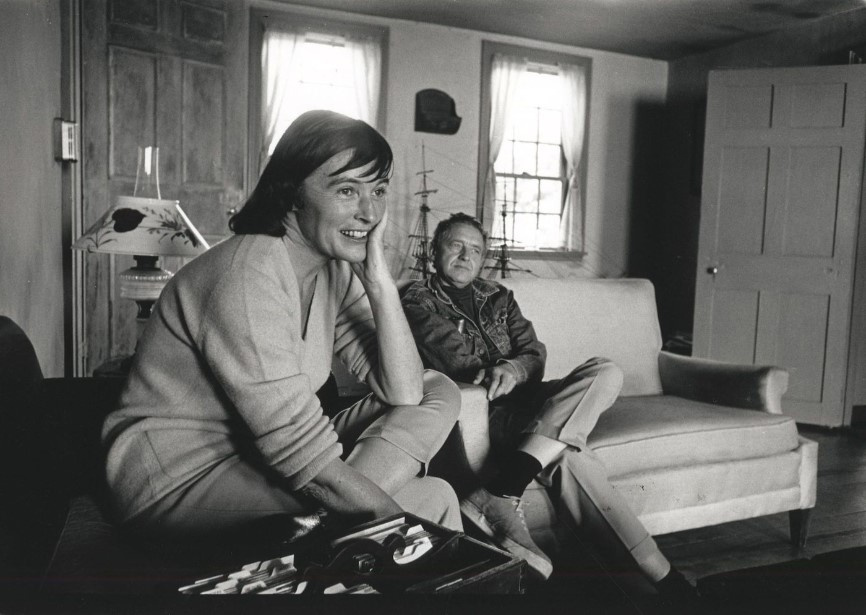

Director and her actor

In 1966, Andrew Wyeth told his biographer Richard Meryman: "Betsy galvanized me at the time I needed it. She’s made me into a painter that I would not have been otherwise. … She made me see more clearly what I wanted."Betsy was also Andrew’s most dedicated curator, who organized his exhibitions and spent endless days cataloguing his work. She once said to the same Richard Meryman: "I am like a director, and I have the greatest actor in the world."

After Andrew Wyeth’s death in 2009, Betsy donated his studio to the Brandywine River Museum of Art, which was organized and opened with her participation. It is now a National Historic Landmark and is open to the public depending on the season. Betsy James Wyeth herself passed away quietly on 21 April 2020 at the 99th year of her life. She is buried next to her husband in the Olson estate.