Inspired by it, the Italian artist, architect, and industrial designer Luigi Serafini created his "Codex Seraphinianus" in 1976−1978 resembling the Voynich manuscript. It was an illustrated encyclopedia of an imaginary world with copious hand-drawn, colored-pencil illustrations of bizarre and fantastical flora , fauna, anatomies, fashions, and foods supplied with no-meaning, asemic script. Luigi Serafini claimed that he wanted his alphabet to convey to the reader the sensation that children feel in front of books they cannot yet understand, although they see that the writing does make sense for adults.

We still do not know if the writer of Voynich manuscript had the same intention 600 years ago, but we definitely feel ourselves as these Serafini’s children looking at the Voynich script’s delicate vellum pages illustrated with botanical drawings, astronomical diagrams, and naked female figures bathing in some mysterious green substance.

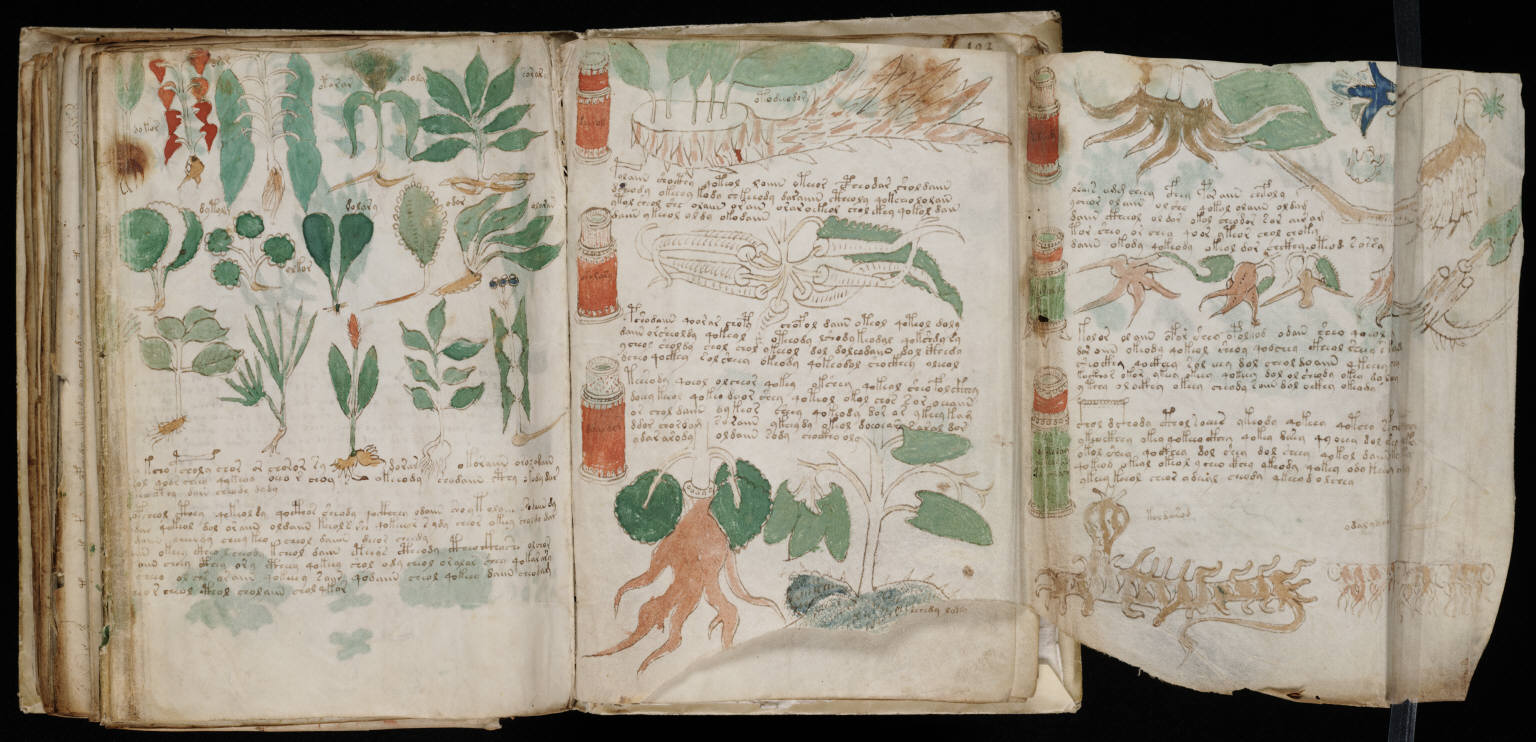

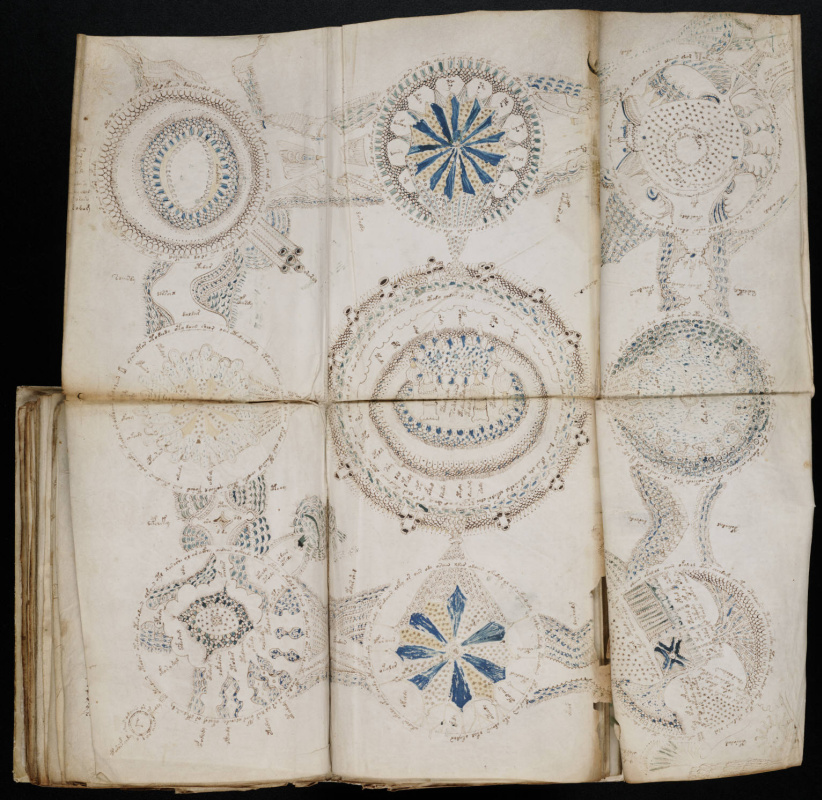

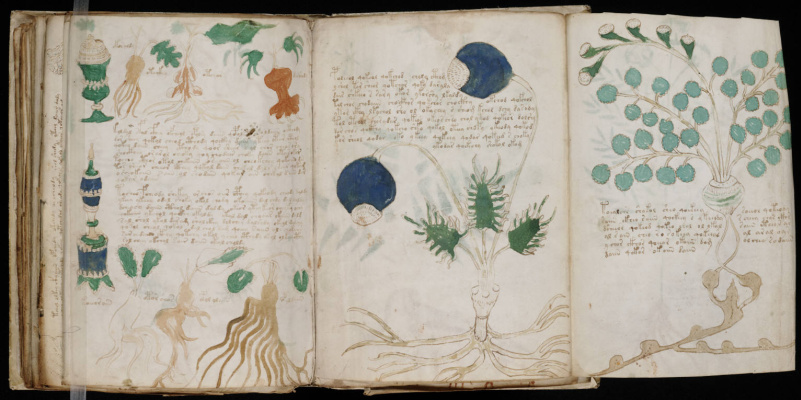

Scholars might have called it a medieval herbal catalogue if only the plants and hairy tubers in it were real, but they are not quite. Most of them don’t match known species. Some astrological-style charts look like zodiac signs but most of the constellations lay within an unknown astrological system. And its naked women immersed in vats of green liquid imply illustrations to some kind of a document on women’s health, but because the text is written in an unknown language, no one can say for sure.

Left: A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

The authorship of the manuscript is still questioned and has led to heated debate "Who is responsible for the manuscript?", with characters as varied as John Dee (1527−1609), an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, occult philosopher and Queen Elizabeth I’s scientific advisor, and renowned Leonardo da Vinci (1452−1519) being posited as its authors. Well, there are some who even have speculated it was written by aliens.

Manuscript ownership can be traced back to the early 17th century. It surfaced last century when several manuscripts from a Jesuit library in Italy was purchased in 1912 by a rare-book dealer Wilfrid Voynich, who has started looking for someone to translate the cipher script.

Today, Voynich manuscript is housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in New Haven, Connecticut, and its high resolution version has been available online for years.

Two months ago, some remarkable news surfaced: the enigmatic Voynich manuscript had finally been decoded by artificial intelligence!

Greg Kondrak of the Canadian University of Alberta’s renowned artificial intelligence lab was one of those who thought that the powerful computer programs could help in decoding the script: "I was intrigued and thought I could contribute something new."His statement was not a mere rhetoric one. Computing labs where he works had already developed software that beat professional players at Texas Hold 'Em, one of the most complex types of poker.

So, computing science professor Greg Kondrak and his co-author, graduate student Bradley Hauer, decided to try to find out what the strange language the script is written in. They took the "United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights" translated into 380 different languages as a sample text and taught the computer algorithm to identify the original language of a text encrypted with substitution ciphers. Then, they came up with a computer program using a series of complex statistical procedures and algorithms to identify the correct language up to 97 per cent of the time, and used it for the Voynich code. The result yielded the hypothesis that the manuscript was written in Hebrew. The scientists found that letters in each word had been reordered and vowels had been dropped.

With help of the computer algorithms and Google Translate scientists read the first sentence: "She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people."

Kondrak agrees that "it's a kind of strange sentence to start a manuscript but it definitely makes sense." Scientists also decoded 72 words in one section that fit in a botanical pharmacopoeia including words like "farmer," "light," "air" and "fire."Kondrak explained that the full meaning of the Voynich manuscript will remain a mystery without historians of ancient Hebrew. Scholars are reluctant to validate his new findings though. Many of them are questioning the methodology Kondrak and Hauer used to arrive at their conclusion.

For instance, Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America, says that an algorithm trained to identify modern languages cannot reliably be used to identify the language of the 15th-century script. "The grammar, spelling, and vocabulary would have been quite different, especially for a manuscript like the Voynich that is scientific in nature," Davis said.

Stephen Skinner, an expert in medieval manuscripts, has already identified the manuscript’s author as a Jewish physician based in northern Italy. In 2017, he claimed that visual clues in each section provide evidence of his theory and one may see them in a range of illustrations where naked women are depicted bathing in green pools supplied by intestinal-like pipes. He said that pictures show communal Jewish baths called mikvah and that they are still used in Orthodox Judaism to clean women after childbirth or menstruation.

Skinner proved his theory on another unconditional evidence: there is a lack of Christian symbolism in the manuscript. "There are no saints or crosses, not even in the cosmological sections," the doctor said. This is very unusual for the time of deep medieval religious superstition, as the Inquisition enforced orthodox religion and punished any hint of heresy.

Skinner claimed that visual clues in the manuscript suggest its author was a Jewish physician and herbalist. He noticed medicinal herbs, such as opium and cannabis, alongside astrological charts and mentioned: "In those days, doctors had to be astrologers as well, so they could determine the nature of an illness and treatment."

And who were the best doctors at the time? Jews, of course. Persecuted in the Inquisition, they still were in high demand as physicians due to their knowledge of Mediterranean botany, Skinner added.

Above: A page from the Voynich Manuscript. Photo courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

"I don’t think they are friendly to this kind of research," he said. "People may be fearing that the computers will replace them."

However, Kondrak believes that there’s much more to the translation than feeding the Voynich into a computer. A good expert in ancient Hebrew and history at the same time could only follow such kind of a clue. He remains hopeful that specialists will come up soon and they will be able to make sense of the syntax and intent of the words he decoded.