Kontrabanda

Description of the artwork «Kontrabanda»

In the mid-1990s, after several wars and civil wars in the Caucasus, remote villages survived almost solely on what they produced: cows, sheep, cheese, butter, herbs, homemade vodka, and tobacco. But certain rare goods had to be obtained through barter, such as flour, horseshoes, oil, ammunition, or a small Korean color TV.

These goods were supplied by professional traders who organized the exchange of sheep for fuel or cigarettes for a horse. Their merchandise was nicknamed “kontrabanda” (Russian: контрабанда), which translates to “smuggled goods.”

Although the trade wasn’t necessarily illegal, it was fraught with danger. Hungry border guards, corrupt policemen, or common robbers might steal money or drive away a flock of sheep at gunpoint. Bad weather also posed a threat: blizzards, avalanches, or a horse falling down a ravine could result in the loss of expensive goods.

But these traders didn’t bring only material goods. Equally important, they brought news from the big cities far away, like Tbilisi, Grozny, or Yerevan. They also brought newspapers, rumors, jokes, and the latest currency exchange rates. These were tough and witty men, resourceful and adaptable.

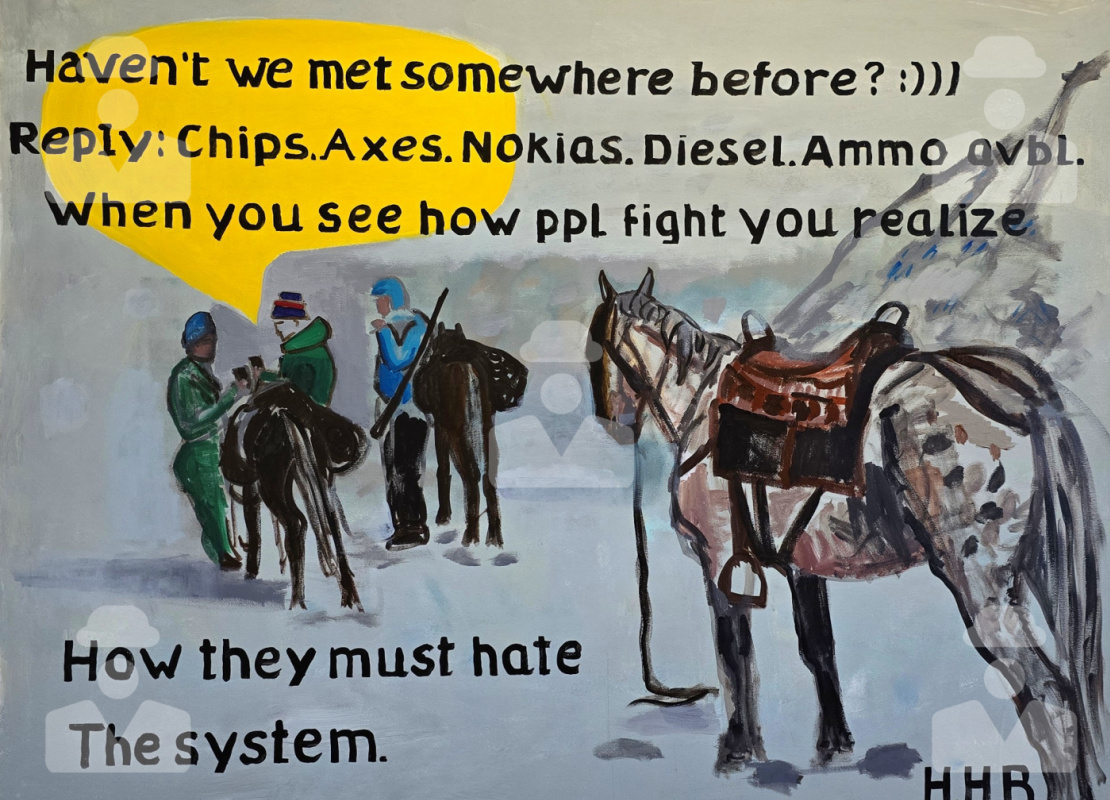

My painting “Kontrabanda” from 2024 is based on an unexpected encounter with such a Caucasus trader on the Arkhoti mountain pass. I remember him as the Ingush man “Mak-Sharif,” who was happy to meet other friendly people in the silent, snowy solitude. He invited us for a chat, and we exchanged cigarettes and jokes. Even a few years later, when my friends from Khevsureti sold me a sturdy red-brown horse, they told me that the horse had come from Ingushetia via Mak-Sharif.

The text in the painting is from a spam email I received a few years ago and saved for its inherent beauty. This painting is 190 x 130 cm in Acrylic on Canvas and part of my Solo show at Vernissage Gallery Tbilisi vom 1–12 November 2024.