log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

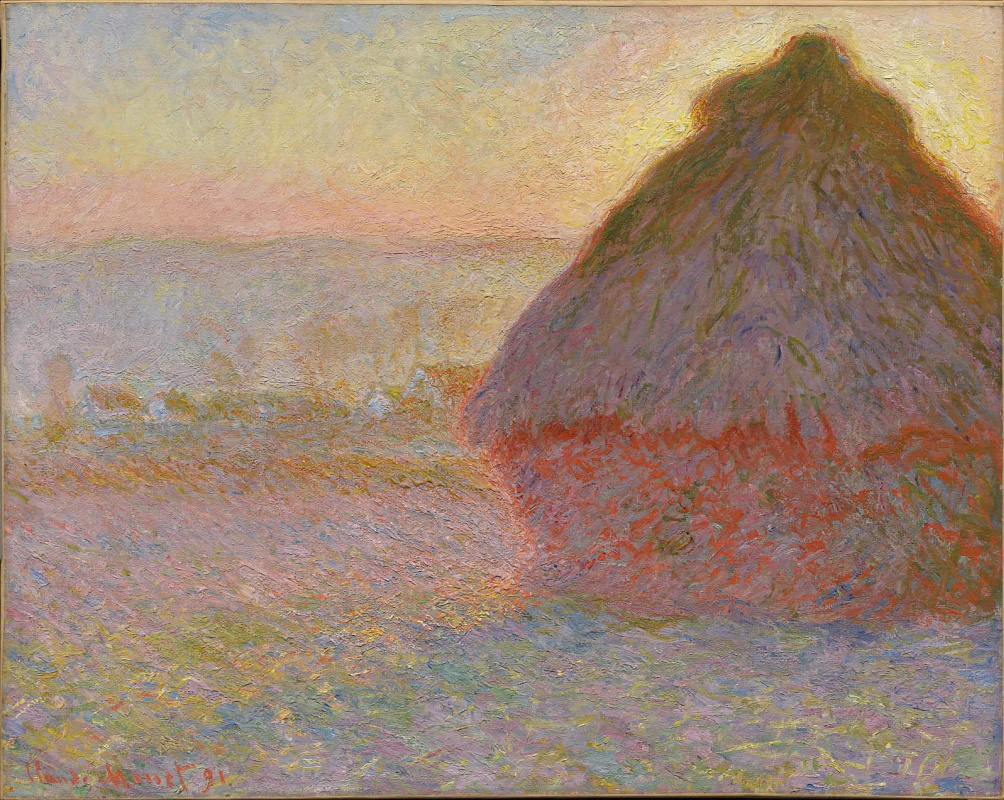

Grainstack (Sunset)

Claude Monet • Pintura, 1891, 73.3×92.7 cm

Descripción del cuadro «Grainstack (Sunset)»

‘My paintings have gone to the savages. Seems like I’m destined to die a failure,’ complained Claude Monet on finding how popular his pictures had become in America.

If you want to see most of the Haystacks series, you have to go to New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis, Farmington, Boston. When Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited the Grainstacks and the Poplars series in his gallery, they sent the French into raptures and aroused overseas art lovers’ purchase interest.

‘People want nothing but Monets, apparently he can’t paint enough pictures to meet the demand. Worst of all they all want Sheaves in the Setting Sun! … Everything he does goes to America at prices of four, five and six thousand francs,’ Camille Pissarro wrote to his son.

At that period, the person particularly close to papa Monet was his stepdaughter Blanche, a real guardian angel for him. She was the only one of his many children, natural as well as adopted, who showed interest in painting and mastered it. At daybreak, they would set off together in quest of motifs. Blanche would push a trolley loaded with papa’s unfinished canvases — it was Claude’s new idea of working on different pictures at different times of the day. He was successful at last, he had paid out the cost of the house and hired a gardener, but only now did he realise that he had found the only possible, though terribly hard way of capturing ‘the fleeting light covering the vegetation everywhere.’ In his trolley, he had the six-o’clock grainstack, the eight-o’clock one, the midday and the afternoon ones, and the ones painted at sunset, in a fog, and on a cloudy day. Sometimes, he started rummaging for a sketch so as not to miss the right lighting (that never lasted longer than 15 to 30 minutes). He picked a canvas that seemed the right one, touched it with quick brushstrokes, kept on modifying it until it turned into quite a new picture. Then, what a surprise it was to come across the very canvas he had failed to find when he needed it!

Four years after Durand-Ruel’s grainstack boom in America, an impressionist exhibition was held in Moscow. One of those who came to look at the artworks by the celebrated French art revolutionaries was a successful lawyer who, a short time before, had been invited to teach Law at a university. Monet’s Grainstack made him stop bewildered and wondering. The painting was absolutely incomprehensible, but the emotions it aroused were far deeper and seemed more real than those from a traditional narrative canvas. He came nearer and read the title of the picture, Grainstack.

The successful 30-year-old lawyer would give up the allure of the professorship. Instead, he would go to Munich to study painting. After fifteen years, he would paint the first abstract watercolour, and his ideas would grow into a theory of colour and shape as the true subject matter of pure art, art for art’s sake. The lawyer’s name was Wassily Kandinsky.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

If you want to see most of the Haystacks series, you have to go to New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Minneapolis, Farmington, Boston. When Paul Durand-Ruel exhibited the Grainstacks and the Poplars series in his gallery, they sent the French into raptures and aroused overseas art lovers’ purchase interest.

‘People want nothing but Monets, apparently he can’t paint enough pictures to meet the demand. Worst of all they all want Sheaves in the Setting Sun! … Everything he does goes to America at prices of four, five and six thousand francs,’ Camille Pissarro wrote to his son.

At that period, the person particularly close to papa Monet was his stepdaughter Blanche, a real guardian angel for him. She was the only one of his many children, natural as well as adopted, who showed interest in painting and mastered it. At daybreak, they would set off together in quest of motifs. Blanche would push a trolley loaded with papa’s unfinished canvases — it was Claude’s new idea of working on different pictures at different times of the day. He was successful at last, he had paid out the cost of the house and hired a gardener, but only now did he realise that he had found the only possible, though terribly hard way of capturing ‘the fleeting light covering the vegetation everywhere.’ In his trolley, he had the six-o’clock grainstack, the eight-o’clock one, the midday and the afternoon ones, and the ones painted at sunset, in a fog, and on a cloudy day. Sometimes, he started rummaging for a sketch so as not to miss the right lighting (that never lasted longer than 15 to 30 minutes). He picked a canvas that seemed the right one, touched it with quick brushstrokes, kept on modifying it until it turned into quite a new picture. Then, what a surprise it was to come across the very canvas he had failed to find when he needed it!

Four years after Durand-Ruel’s grainstack boom in America, an impressionist exhibition was held in Moscow. One of those who came to look at the artworks by the celebrated French art revolutionaries was a successful lawyer who, a short time before, had been invited to teach Law at a university. Monet’s Grainstack made him stop bewildered and wondering. The painting was absolutely incomprehensible, but the emotions it aroused were far deeper and seemed more real than those from a traditional narrative canvas. He came nearer and read the title of the picture, Grainstack.

The successful 30-year-old lawyer would give up the allure of the professorship. Instead, he would go to Munich to study painting. After fifteen years, he would paint the first abstract watercolour, and his ideas would grow into a theory of colour and shape as the true subject matter of pure art, art for art’s sake. The lawyer’s name was Wassily Kandinsky.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova