log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

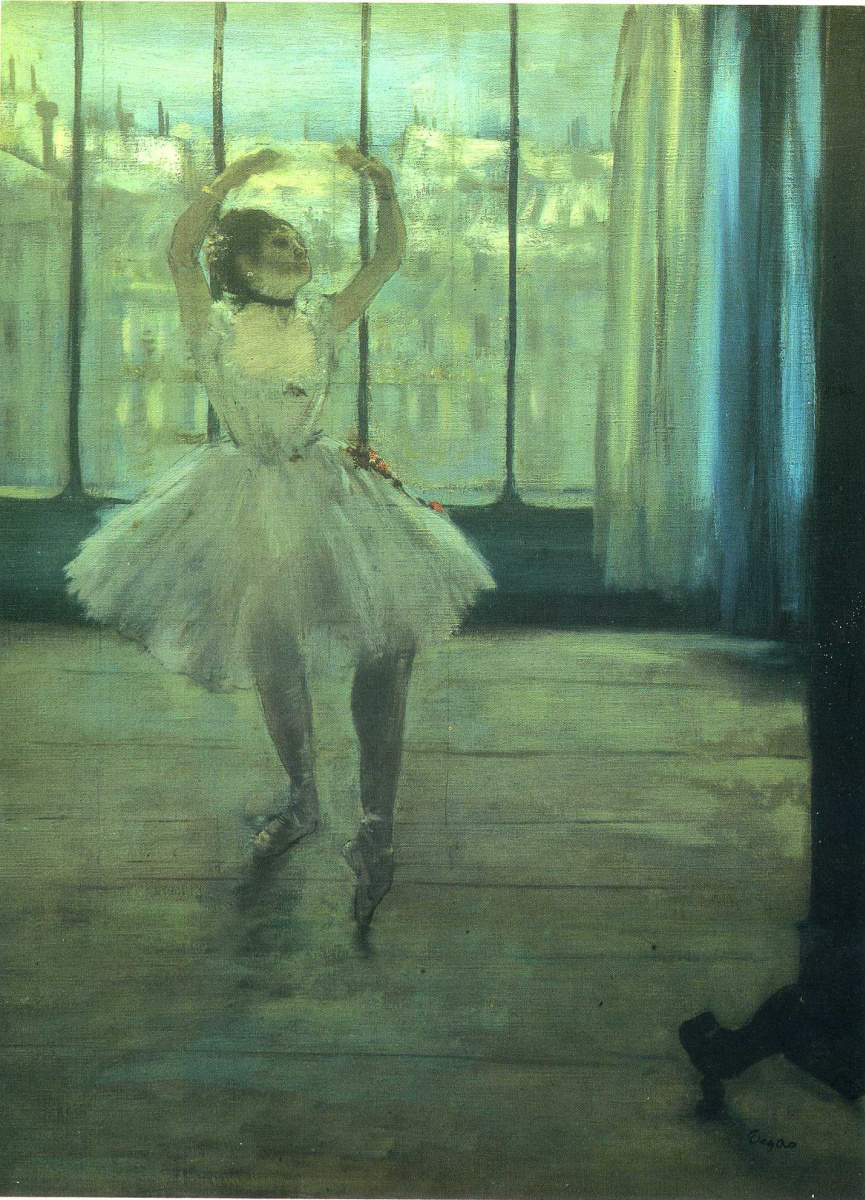

Dancer at the Photographer’s Studio

Edgar Degas • Pintura, 1875, 65×50 cm

Descripción del cuadro «Dancer at the Photographer’s Studio»

In 1874, French author Edmond de Goncourt visited Degas, then totally unheard of, in his studio, and noted in his diary, ‘Out of all the subjects in modern life he has chosen washerwomen and ballet dancers … it is a world of pink and white … the most delightful of pretexts for using pale, soft tints.’ Much later, Degas would confirm what Goncourt guessed: ballet was but a pretext. Not for limiting his palette to the colors of yoghurt, of course, but for studying people in motion. Degas produced hundreds of pictures of ballet dancers scratching their bodies, working the tired muscles of their back and legs, having boring ballet classes, pulling up shoulder straps, awkwardly balancing at the barre, adjusting a ballet shoe, or tidying their hair.

There are two things Degas is popularly known for: he always portrayed girl dancers, and he hated women. Outraged critics from French newspapers accused him of loathing the female body, portraying women in the most unnatural and detesting postures. Even nowadays, some authors and exhibition critics say he was a sexually impotent man who failed to have a personal life, a voyeur who wore his models down by contorted positions and long sitting sessions. They say the women he drew were ‘like performing animals, they’re like animals in the zoo.’

However, is it not a strange choice for an artist to spend the whole life painting what he hated?

Dancer at the Photographer’s Studio is one of the many awkwardly postured women painted by him. She is shown as if being portrayed by someone no one notices and no one expects to be present in the room. The girl is looking another way, at the photographer beyond the frame, posing for him, not for the painter. The angle we are looking at does not show her to advantage. This is, so to say, the reverse of the glossy photo she is exerting herself for.

But from where we are looking at her, we can see how strenuously she is trying to stand still in her eye-catching, theatrical pose. The result is something twisted and unnatural. From this, unwanted point, it is easier to imagine the real daily routine of a ballet girl: blistered toes, tired arms, aching legs, day-to-day boredom, years of training and hopes for big roles. Seeing things from this point, it is harder to admire, but easier to learn and understand.

All his life, Degas faced intellectual challenges: how to show, most accurately, the deepest truth of his days, while staying within the classical artistic tradition. He would climb up ladders, and hide in the orchestra pit, behind the stage curtains and columns — only to find the perfect viewpoint for himself — for an artist who is not a mere artist, but a background actor, an eyewitness of his time, who happened to be observing the truth. Girl dancers became his obsession to be studied, a pack of expressive, repeating movements, the rhythm of life itself.

At the age of 52, Degas wrote to his friend, ‘With the exception of the heart, it seems to me that everything within me is growing old in proportion. And even this heart of mine has something artificial. The dancers have sewn it into a bag of pink satin, pink satin slightly faded, like their dancing shoes.’

A women-hater? Not Degas.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

There are two things Degas is popularly known for: he always portrayed girl dancers, and he hated women. Outraged critics from French newspapers accused him of loathing the female body, portraying women in the most unnatural and detesting postures. Even nowadays, some authors and exhibition critics say he was a sexually impotent man who failed to have a personal life, a voyeur who wore his models down by contorted positions and long sitting sessions. They say the women he drew were ‘like performing animals, they’re like animals in the zoo.’

However, is it not a strange choice for an artist to spend the whole life painting what he hated?

Dancer at the Photographer’s Studio is one of the many awkwardly postured women painted by him. She is shown as if being portrayed by someone no one notices and no one expects to be present in the room. The girl is looking another way, at the photographer beyond the frame, posing for him, not for the painter. The angle we are looking at does not show her to advantage. This is, so to say, the reverse of the glossy photo she is exerting herself for.

But from where we are looking at her, we can see how strenuously she is trying to stand still in her eye-catching, theatrical pose. The result is something twisted and unnatural. From this, unwanted point, it is easier to imagine the real daily routine of a ballet girl: blistered toes, tired arms, aching legs, day-to-day boredom, years of training and hopes for big roles. Seeing things from this point, it is harder to admire, but easier to learn and understand.

All his life, Degas faced intellectual challenges: how to show, most accurately, the deepest truth of his days, while staying within the classical artistic tradition. He would climb up ladders, and hide in the orchestra pit, behind the stage curtains and columns — only to find the perfect viewpoint for himself — for an artist who is not a mere artist, but a background actor, an eyewitness of his time, who happened to be observing the truth. Girl dancers became his obsession to be studied, a pack of expressive, repeating movements, the rhythm of life itself.

At the age of 52, Degas wrote to his friend, ‘With the exception of the heart, it seems to me that everything within me is growing old in proportion. And even this heart of mine has something artificial. The dancers have sewn it into a bag of pink satin, pink satin slightly faded, like their dancing shoes.’

A women-hater? Not Degas.

Author: Anna Sidelnikova