Ever unmercenary natural-born leader, master of the outrageous, a world celebrity, a talented liar and a real street fighter — strangely enough, all this is about one person.

Malevich was a born hypnotist possessing strong vibes and powerful charisma. He turned many people into his belief only with "the weight of his personality". He was unconditionally trusted and willingly followed. Once Kazimir Severinovich was passing by an art school. The entrants who were about to take the entrance exams whispered "Malevich, there he goes". "They were trying to touch me secretly in order to pass their examination. They were stroking my back softly, but I went without giving a sign that I had noticed that, — Malevich told, — I didn’t want to frighten off their belief".

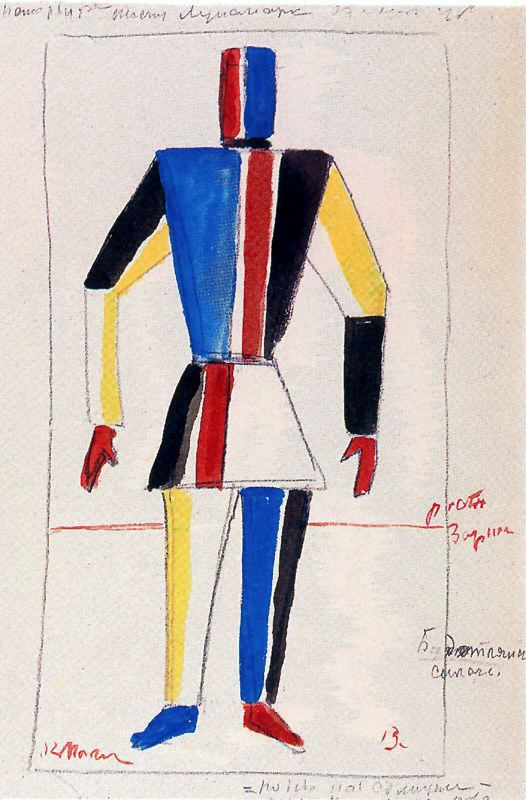

Proletarians of all countries

1918, 27×37 cm

In 1905 Kazimir Malevich was fighting in the battle for Krasnaya Presnya. At least, he told so:

"I got a "bulldog" and the bullets. It was a real war. I joined a group of men with their pockets full of bullets and revolvers of various systems. The hunters accompanied us. We were heading to the Red gate, there was a fight over there. We were turned to Sukharev tower. The fences began to crack, we were piling up a barricade… Soldiers were quickly approaching to the square. A command followed and the soldiers were ready to shoot. We let it know to the barricade. In a moment we were given a quiet command. A salvo fire made the soldiers wrong-footed, though they were ready for attack. We shot time after time. Very quickly I ran out of the five bullets charged to my revolver".

Trying to get rescued from the pursuit, Malevich rushed into his friend’s house. The door was intentionally left unlocked. They hid the revolver, lighted cigarettes, poured out vodka, "had a shot, it rushed down to the heels, — I was hungry, and in such cases it always rushes down to the heels. He began to sing, "In the field there stood a birch". I was signing in a bass voice.

— Sing louder!

There followed a knock to the door. Still sitting, we shouted to come in. A noncom enters with the revolver in his hand. Two soldiers.

— Any fugitives here?

— Which fugitives? Why not sharing a glass with us? It’s my birthday today so we are celebrating…

The noncom relented at once, had a drink, asked for another one, so we had to pour it to him… In the morning, holding a basket, I came out together with the hostess who was going to a shop. We left the yard as if nothing had happened."

"I got a "bulldog" and the bullets. It was a real war. I joined a group of men with their pockets full of bullets and revolvers of various systems. The hunters accompanied us. We were heading to the Red gate, there was a fight over there. We were turned to Sukharev tower. The fences began to crack, we were piling up a barricade… Soldiers were quickly approaching to the square. A command followed and the soldiers were ready to shoot. We let it know to the barricade. In a moment we were given a quiet command. A salvo fire made the soldiers wrong-footed, though they were ready for attack. We shot time after time. Very quickly I ran out of the five bullets charged to my revolver".

Trying to get rescued from the pursuit, Malevich rushed into his friend’s house. The door was intentionally left unlocked. They hid the revolver, lighted cigarettes, poured out vodka, "had a shot, it rushed down to the heels, — I was hungry, and in such cases it always rushes down to the heels. He began to sing, "In the field there stood a birch". I was signing in a bass voice.

— Sing louder!

There followed a knock to the door. Still sitting, we shouted to come in. A noncom enters with the revolver in his hand. Two soldiers.

— Any fugitives here?

— Which fugitives? Why not sharing a glass with us? It’s my birthday today so we are celebrating…

The noncom relented at once, had a drink, asked for another one, so we had to pour it to him… In the morning, holding a basket, I came out together with the hostess who was going to a shop. We left the yard as if nothing had happened."

Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Klyunkov, Alexey Morgunov (from left to right). Moscow, March 1, 1914.

However, one should not believe in all the things Malevich told or wrote about himself — Kazimir Severinovich was something of a liar. He invented stories, where he appeared a leading juvenil, a daredevil or a ver, or madcap or lone rioter. He had an especially thankful listener: it was his credulous friend Ivan Klyunkov, who accepted his stories at face value, then retelling them simple-heartedly to others.

Once Malevich told Klyunkov that he had left Moscow school of painting, sculpture and architecture, as did not get on with retrograde teachers there. Allegedly the teacher asked to explain why the model appeared green in his canvas, and Kazimir answered that it was the way he liked it and the way he saw it. Actually he never entered Moscow school of painting, sculpture and architecture in spite of his four attempts. Another time he told Klyunkov rather heartbreaking story. Supposedly he was walking the streets of Moscow when he noticed funeral procession with a little girl in the coffin and her mother and two senior children following. And suddenly Malevich realized that it was his wife and his children, this funeral being that of his youngest daughter!"Eh, why I am not an Itenerant? What a subject for a painting, what a subject!" - Malevich exclaimed pitifully. Surely he had no third daughter with his first marriage.

Once Malevich told Klyunkov that he had left Moscow school of painting, sculpture and architecture, as did not get on with retrograde teachers there. Allegedly the teacher asked to explain why the model appeared green in his canvas, and Kazimir answered that it was the way he liked it and the way he saw it. Actually he never entered Moscow school of painting, sculpture and architecture in spite of his four attempts. Another time he told Klyunkov rather heartbreaking story. Supposedly he was walking the streets of Moscow when he noticed funeral procession with a little girl in the coffin and her mother and two senior children following. And suddenly Malevich realized that it was his wife and his children, this funeral being that of his youngest daughter!"Eh, why I am not an Itenerant? What a subject for a painting, what a subject!" - Malevich exclaimed pitifully. Surely he had no third daughter with his first marriage.

Budetlyanskie strongman

1920-th

, 53.3×36.1 cm

Malevich possessed outstanding physical strength. He got up early in the morning, kindled a stove and went for an obligatory morning walk. In general, he walked much, he also juggled two stones' dumbbells. Malevich was not timid at all.

Having heard plenty of stories about his wild youth, Sergey Eisenstein wrote a tale Nemchinov post. "Thunk-thunk! — the stage-director of The Potemkin Battleship wrote. — A blow into two jaws was heard very close. "Оh" by a plump maid and a scream of the maid, who gave a shawl, merged and vanished together. The blond fellow rolled over after a kick to his teeth and fell into a grey-ash-colored dust with his nose. The stranger stood still throwing rare, but well-aimed short shots with his fist to the temple of the first, then to the other’s cheek-bone, under the eye, into the ear, into the teeth. Blood and saliva were splashing to dust. The maids have disappeared. And all that was done so evenly and quietly, but for the wheeze and knocks of the fist on the bones, that a hen after recovering from the first fright, phlegmatically continued to peck something, only now and then being surprised to the sparks of blood rolling on dry dusty sand".

When Malevich was asked to "explain cubism" to the listeners of party school, with his even breath he was telling them about rotation, unity of time and space, a look from all points of view simultaneously. And to make it clearer he was turning an enormous heavy wooden lectern in his hands. Malevich was 50 years old then in a process.

Having heard plenty of stories about his wild youth, Sergey Eisenstein wrote a tale Nemchinov post. "Thunk-thunk! — the stage-director of The Potemkin Battleship wrote. — A blow into two jaws was heard very close. "Оh" by a plump maid and a scream of the maid, who gave a shawl, merged and vanished together. The blond fellow rolled over after a kick to his teeth and fell into a grey-ash-colored dust with his nose. The stranger stood still throwing rare, but well-aimed short shots with his fist to the temple of the first, then to the other’s cheek-bone, under the eye, into the ear, into the teeth. Blood and saliva were splashing to dust. The maids have disappeared. And all that was done so evenly and quietly, but for the wheeze and knocks of the fist on the bones, that a hen after recovering from the first fright, phlegmatically continued to peck something, only now and then being surprised to the sparks of blood rolling on dry dusty sand".

When Malevich was asked to "explain cubism" to the listeners of party school, with his even breath he was telling them about rotation, unity of time and space, a look from all points of view simultaneously. And to make it clearer he was turning an enormous heavy wooden lectern in his hands. Malevich was 50 years old then in a process.

Kazimir Malevich in front of his works at the Museum of artistic culture, Petrograd, 1924.

Kazimir Malevich was a master of the outrageous. In spring of 1916 an artist Vladimir Tatlin arranged "The shop" exhibition in Moscow. Being a constructivist, Tatlin was the irreconcilable critic of Malevich and his theories. He forbade to exhibit suprematic works at "The shop". But Kazimir Severinovich was not the one to yield, so he decided to become an exhibit himself. He came to the exhibition with the numbers "0,1" written on his forehrad and the handwritten placard at his back: "I am the apostle of new concepts in art and SURGEON of REASON who sat down on the throne of creativity pride, I declare THE ACADEMY to be the stable of petty bourgeois".

However, Tatlin was ready with his tongue. According to a popular tale, once he knocked out a chair from under Malevich suggesting him to sit on geometry and color. And at the artist’s funerals, looking at Malevich in specially designed suprematic coffin, Tatlin said: "He's pretending!"

However, Tatlin was ready with his tongue. According to a popular tale, once he knocked out a chair from under Malevich suggesting him to sit on geometry and color. And at the artist’s funerals, looking at Malevich in specially designed suprematic coffin, Tatlin said: "He's pretending!"

Supremus No. 56

1916, 80.5×71 cm

In general, Malevich had many enemies. Bright, strong, emphatic in his judgements — he irritated someone, the others were jealous. And if Tatlin argued with Malevich about art, the others were seizing any opportunity to play off old scores with him in everyday life. It became especially easy in early 30s, when Joint State Political Directorate actively began to clean out "cultural space". For example, a poet and an avant-garde artist Igor Terentyev, who was arrested in 1931, in his confessions reported that Malevich’s pointless painting "was a method of the coded transmittal of the information about Soviet Union abroad". According to Terentyev all these squares, architectones etc. were actually the plans of Soviet secret facilities.

Upon his acquaintance with Malevich, Chagall took off from his native city of Vitebsk like a cork out of the bottle of champagn.

(Marc Chagall. Over Vitebsk)

Malevich made Vitebsk too hot for Marc Chagall. There are many blind-spots in the history of the quarrel between Kazimir Severinovich and Marc Zakharovich. The most widespread version says that Chagall ran away from Vitebsk because of Malevich. In 1919 Marc Chagall founded Folk art school in the native city of Vitebsk. The same year Malevich began to run his workshop there and organized the artistic group Unovis (Founders of the new art), that eventually looked somewhat of a sect. Chagall tried to resist the attempts of Malevich and his followers (the art school teachers joined them soon) to reform the teaching system. But it was difficult to compete with a natural born leader Malevich. "Another teacher living in the Academy’s apartment surrounded himself with the female admirers of this mystic "suprematism"… — Chagall wrote. — When I once again left to get bread, paints and money for the school, my teachers excited a riot pulling the students in it. May God forgive them! And those, who had got a shelter and a slice of bread from me, decreeed to give me the gate. I had 24 hours to leave the school."

Well, even if it was so, Malevich, rather, did service to Chagall, not the opposite. Soon after that Chagall emigrated, was granted French citizenship, married two more times, was awarded the Large cross of the Legion of Honour and died in Provence at the age of 97.

Well, even if it was so, Malevich, rather, did service to Chagall, not the opposite. Soon after that Chagall emigrated, was granted French citizenship, married two more times, was awarded the Large cross of the Legion of Honour and died in Provence at the age of 97.

Malevich with his third wife Natalya Manchenko short before his death. Leningrad, 1935.

During all his life Malevich was the embodiment of a typical image of the poor artist. In his first years in Moscow he used to lose consciousness from hunger, and shortly before his death, being seriously il, in letters to his wife Malevich complained of not being able to get to the hospital as he got holes in his ends and had no overshoes to put on.

When his exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin took place in 1927, Malevich was scarce of money as usual. The ministry of culture was not going to cover the ticket for him, so Malevich wrote a letter to Chief Scientific Department suggesting to let him go to France via Warsaw and Germany on foot: leaving from Leningrad on May 15 in order to reach Paris on November 1. Apparently, stunned by the absurdity of the request, the officials gave him the money. In Poland and Germany Malevich enjoyed his glory. "My opinion is considered to be an axiom. In a word, the glory is pouring onto me, — he wrote from there. — But the only drawback is that nobody can guess to put some tenders between the leaves of my glory. They naturally think that a famous artist like me is fixed up with everything."

When his exhibitions in Warsaw and Berlin took place in 1927, Malevich was scarce of money as usual. The ministry of culture was not going to cover the ticket for him, so Malevich wrote a letter to Chief Scientific Department suggesting to let him go to France via Warsaw and Germany on foot: leaving from Leningrad on May 15 in order to reach Paris on November 1. Apparently, stunned by the absurdity of the request, the officials gave him the money. In Poland and Germany Malevich enjoyed his glory. "My opinion is considered to be an axiom. In a word, the glory is pouring onto me, — he wrote from there. — But the only drawback is that nobody can guess to put some tenders between the leaves of my glory. They naturally think that a famous artist like me is fixed up with everything."

It was not Malevich who designed the coffin he was buried in. It was a popular legend, however having a certain degree of truth. Once Malevich talked to his student Konstantin Rozhdestvensky about death and funerals, but in general, and not of his. In his opinion a deceased had to lie with one’s arms stretched, the face upward, as if hugging the sky, the universe and taking the form of a cross. Then Malevich did a few sketches (he rarely parted with a pencil, constantly sketching something during conversations). After the artist’s death his students — Konstantin Rozhdestvensky and Nikolai Suietin drafted the project of the coffin and took it to the carpenter. They painted the coffin green, black and white, placing the image of a red circle at foot, and a black square at head.

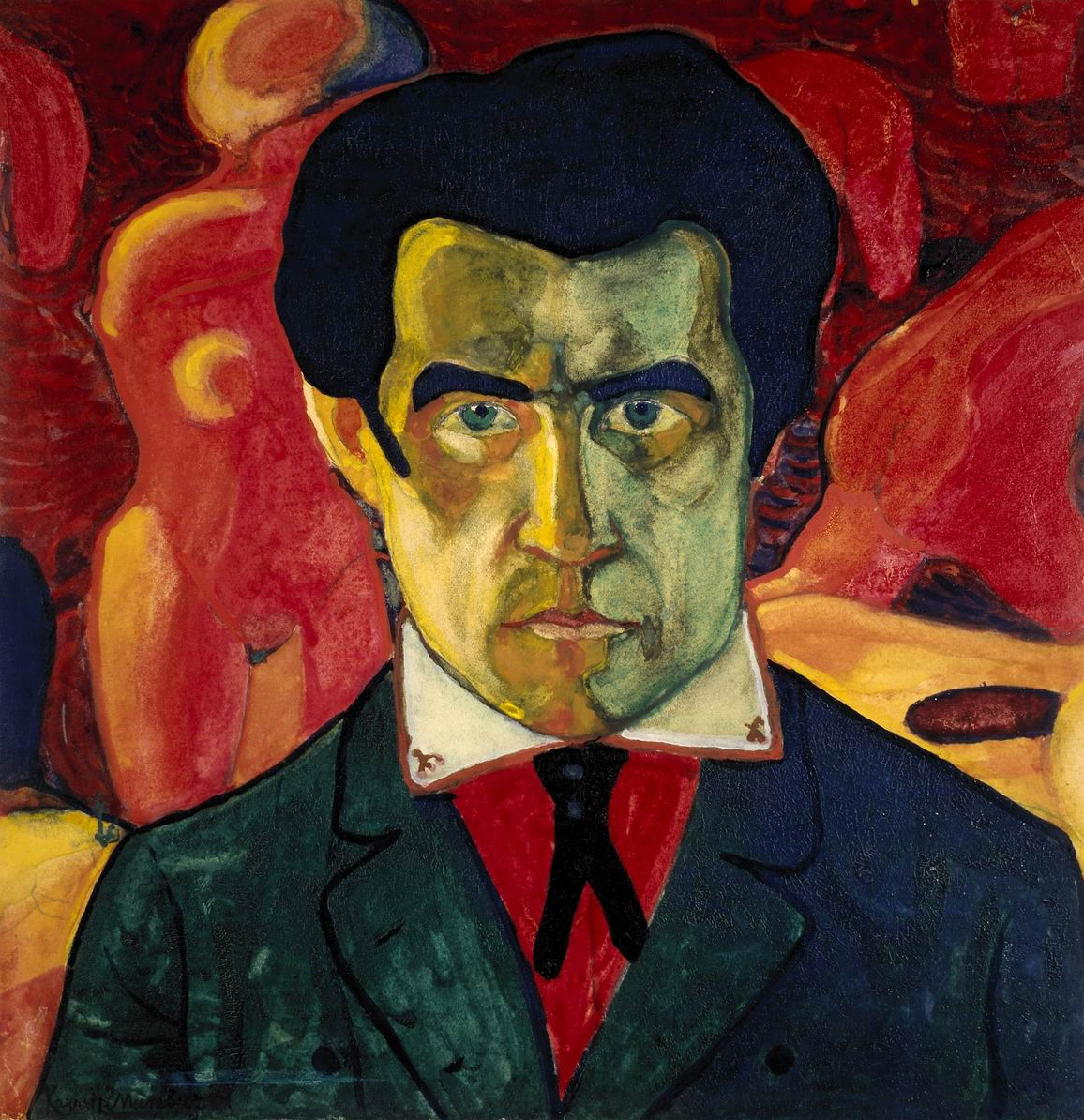

Title illustration: Kazimir Malevich Self Portrait.

Written by Andrew Zimoglyadov

Written by Andrew Zimoglyadov