Wings of salvation

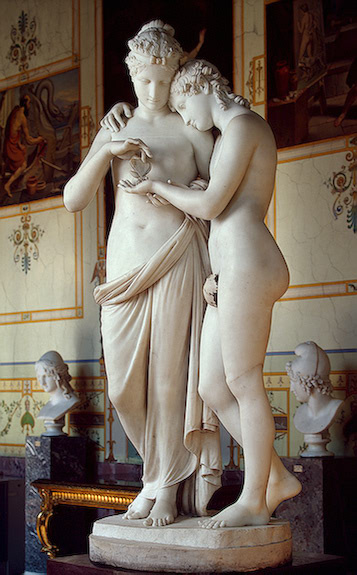

A butterfly that flits out of her confinement has become a representation of the divine cycle, death and resurrection. As a symbol of immortality, it can be found in Greek, Roman, and Ancient Egyptian myths. But none other than the Ancient Greek recognised a butterfly as a symbol of the soul: those gracious things flying in freedom are a natural equivalent of the freedom of human spirit as we understand it, and the Greek word ‘psyche' stands both for the butterfly and for the soul.In Dosso Dossi’s canvas Jupiter, Mercury, and Virtue (1522—1524), butterflies are featured in a curious way. The painter shows Mercury who does not let Virtue into Jupiter’s palace because the god is busy painting butterflies and cucumber blossoms. Thus, creative leisure pursuits appear to be of greater importance for the Olympians than their responsibilities.

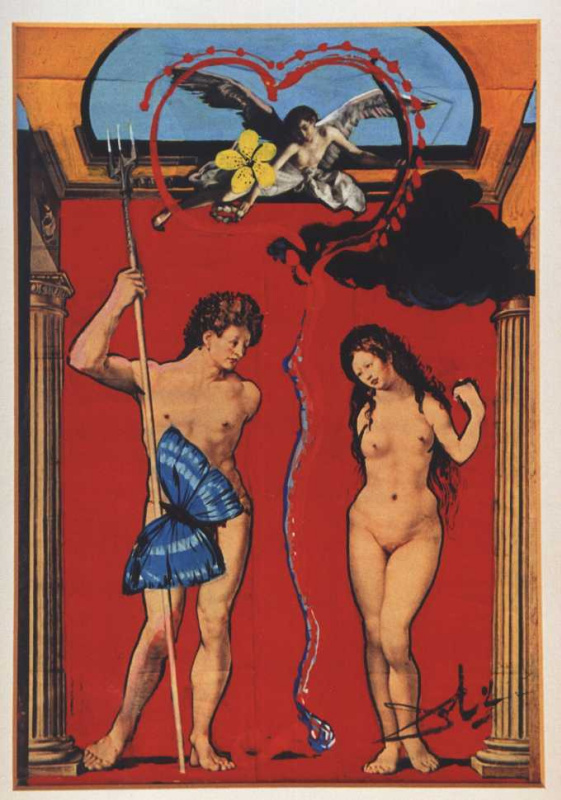

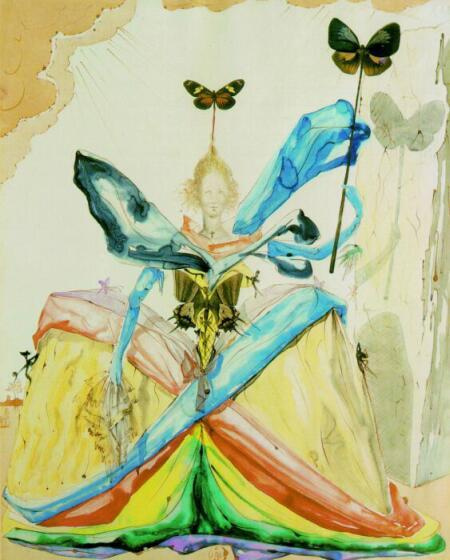

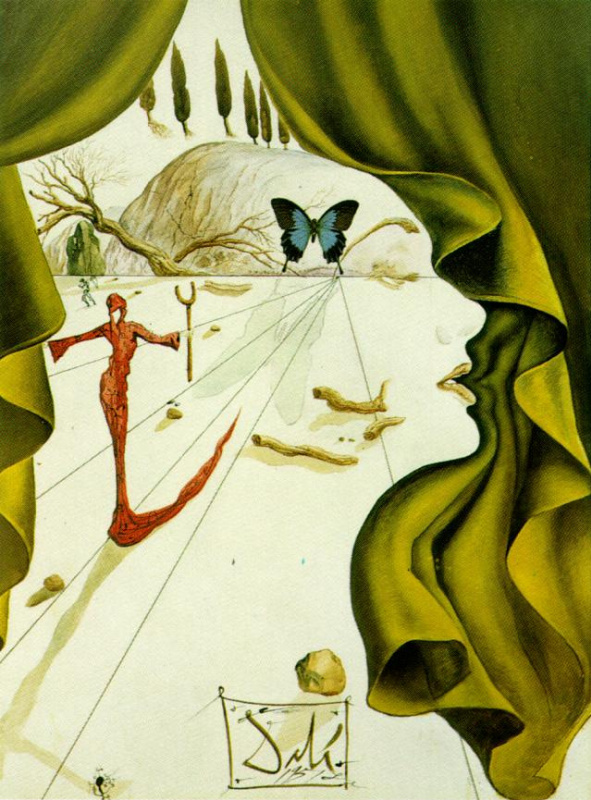

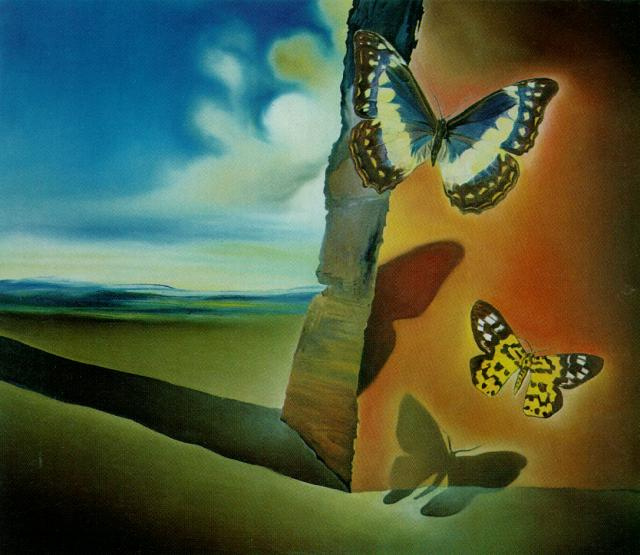

Many a butterfly can be found in canvases by Salvador Dalí, who loved macabre subjects.

The dragonfly of Love

The frolicking dragonfly, as well as most insects, was hardly favoured by Christianity — rather, it was viewed as one of the Devil’s forms. So, if in a picture, the baby Jesus is tightly gripping an insect in his little hand, it is more than just mischief, but an evidence of the triumph of Good over Evil.The Beautiful Leukanida

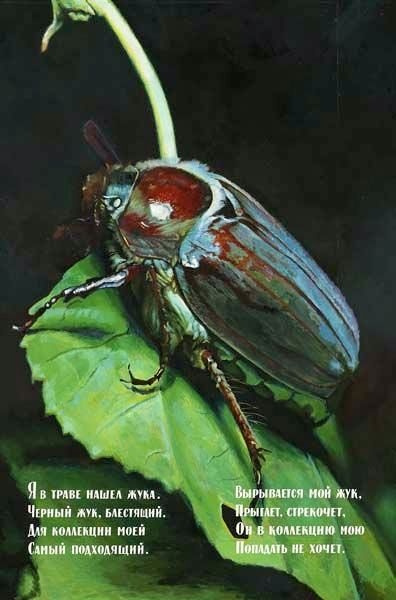

Like many unusually-looking insects, the stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) used to be believed to possess magical power. And its presence in religious paintings must have been due to its symbolic significance for then Christians. A stag was frequently used in Christian pictures as a symbol of Christ, who was considered the guardian of plants and animals, and whose birth defeated evil and brought salvation.The German painter and draughtsman Hans Hoffmann (1530—1592), the leading figure among those who followed and developed Albrecht Dürer's traditions, was so assiduous in copying his hero’s pictures, that many of his works were later sold as Dürer's originals.

For honey, a fly will even come from Baghdad

In the 17th century, flies and other pests were often placed in pictures to protect the commissioners' homes from them. But prior to this, flies had, too, frequently ‘run' on the margins of medieval manuscripts and horologia (Books of hours) as decorative elements. As early as in the 15th century, they found their way into pictures. For some time, they were used as religious symbols of sin, decay, death, and melancholy. Besides, in Christianity, flies are related to Beelzebub (Baalzebub), a deity of the ancient Assyrians and Phoenicians, who in the New Testament was titled ‘chief of the devils.' There is a legend that, with flies, he once sent plague upon Canaan. But in the history of painting, the annoying bug that is still associated with filth, had its moment of glory when it was used to prove excellent artistic mastery. The anecdote is told by Giorgio Vasari in his The Lives. Once Giotto, an apprentice of the Florentine painter Cimabue, painted a fly on a face in one of his teacher’s pictures when Cimabue was absent. The fly was so remarkably lifelike that Cimabue, on his return, tried several times to brush it off. Well, the annoying nature of this bug is really symbolic.Having a spider is having its cobweb

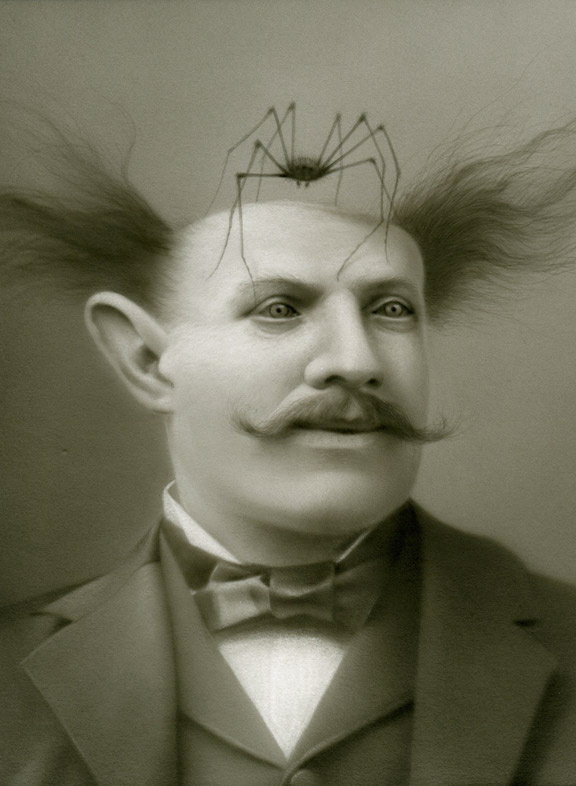

People have always detested spiders and their webs. That is why the arthropod was associated with evil designs, scheming, and fornication. However, this wildlife wonder, too, has found its place in art. As a symbol of fear and sorrow, it can be seen in early works by the French symbolist painter Odilon Redon. Later, he switched to the multi-coloured palette and started painting flowers — and butterflies!

The most famous and the largest spider — to be exact, a female one — is called Maman. It is a nine-metre bronze, stainless steel, and marble sculpture by Louise Bourgeois. That is how the author herself explains the choice of the character which is obviously dear to her, ‘The Spider is an ode to my mother. She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver. My family was in the business of tapestry restoration, and my mother was in charge of the workshop. Like spiders, my mother was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. … So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother.'

Chosen by Napoleon

Iconography is often quite inconsistent in treating insects. They can be viewed as something evil and as a means of salvation and an object of devotion. The bee, a symbol of self-sacrifice, can also signify transience, or the onset of an illness, or it can be a reminder of death.But the busy supplier of honey once had its glory hour when it ascended the throne as a decoration of Napoleon’s royal mantle.

The thing was that, because of his Corsican descent, Napoleon had no right on a coat of arms with the fleur-de-lis, an old heraldic symbol. Then, as his personal emblem, he chose the bee, because, from a distance, it looked like the fleur-de-lis turned upside down. The bee, a symbol of immortality and rebirth, became a link between the new dynasty and the ancient roots of the French state. Wearing, during his coronation, a mantle with the Merovingian bees (they were the artefacts found in 1653, in Tournai, in the grave of Childeric, Merovech’s son), Napoleon demonstrated that he was a rightful successor to the rulers of the past.

The mystery performance of the still life

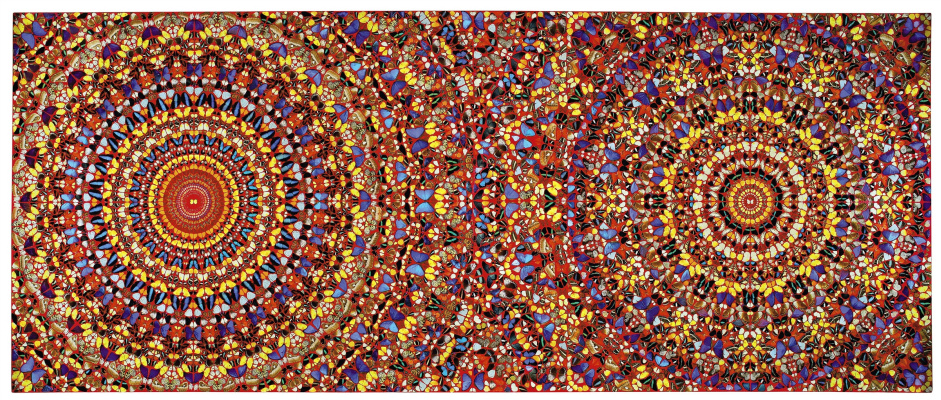

On abandoning canonical iconography and pious meditations, artists focused on ordinary, everyday objects — and directed their eyes down. And found there a most diverse and yet unexplored world. However, they did not give up trying to find the Creator’s hand in the harmony of images. In still lifes painted in the 17th century, objects often contain a hidden allegory of all mundane, of the certainty of death (Vanitas), of the Holy Passion and the Resurrection. In these allegories, bugs and butterflies always play certain roles like actors in a medieval mystery play.How to creep into auctions and exhibitions

The scandal-ridden Belgian artist Jan Fabre’s fondness of insects is hereditary: his grandfather was the celebrated entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre, the author of the book Insect Life. Jan’s striking exhibition in Kiev aroused curiosity of the sophisticated public, and the shocking exposition in the Hermitage, Saint Petersburg, caused a serious scandal. One of Fabre’s notorious techniques is mosaic made of iridescent wings of jewel beetles. He used them to cover the surface of, for example, the ceilings and chandeliers of the royal palace in Brussels — thus protesting against his country’s imperialistic past. Léopold II and his policy of the annexation of the Congo region (actually it was converting the territory to the king’s personal use) resulted in the depopulation of Congo from 30 million people in 1884 to 15 million in 1915. For Fabre’s installations and sculptures, jewel beetles were delivered directly from Congo (where they are food, like oysters in Europe) — the artist had settled this with restaurant-keepers.