She is 99 and she still paints. Ten years with someone who did not spare his loved ones — why didn’t she just become Picasso’s another refused muse? Is it because she was young when he was already old, or is it thanks to her father who wanted a son and tempered his daughter properly? Did her own talent, high self-esteem and persistent craving for art, which was salvation, play a role? At first, Picasso compared her to a beautiful flower, and later, in her scandalous book, she called the genius a Bluebeard.

By the time she met Pablo Picasso, Françoise Gilot was quite an independently-minded person — she was only 21 years old, Picasso was 61. Françoise's father was a successful entrepreneur who worked in the agrochemical industry. Her mother was wonderful at painting and was fluent in watercolour technique. It was she who became the first teacher of her talented daughter. Being an ardent opponent of pencil and eraser, she taught Françoise to paint with watercolours right away so that she would make as few mistakes as possible. At the age of thirteen, the girl began to take lessons from her mother’s teacher, Mlle Meuge; a year later she learnt ceramics, and at the age of fifteen she began to study with the engraver artist Jacques Beurdeley.

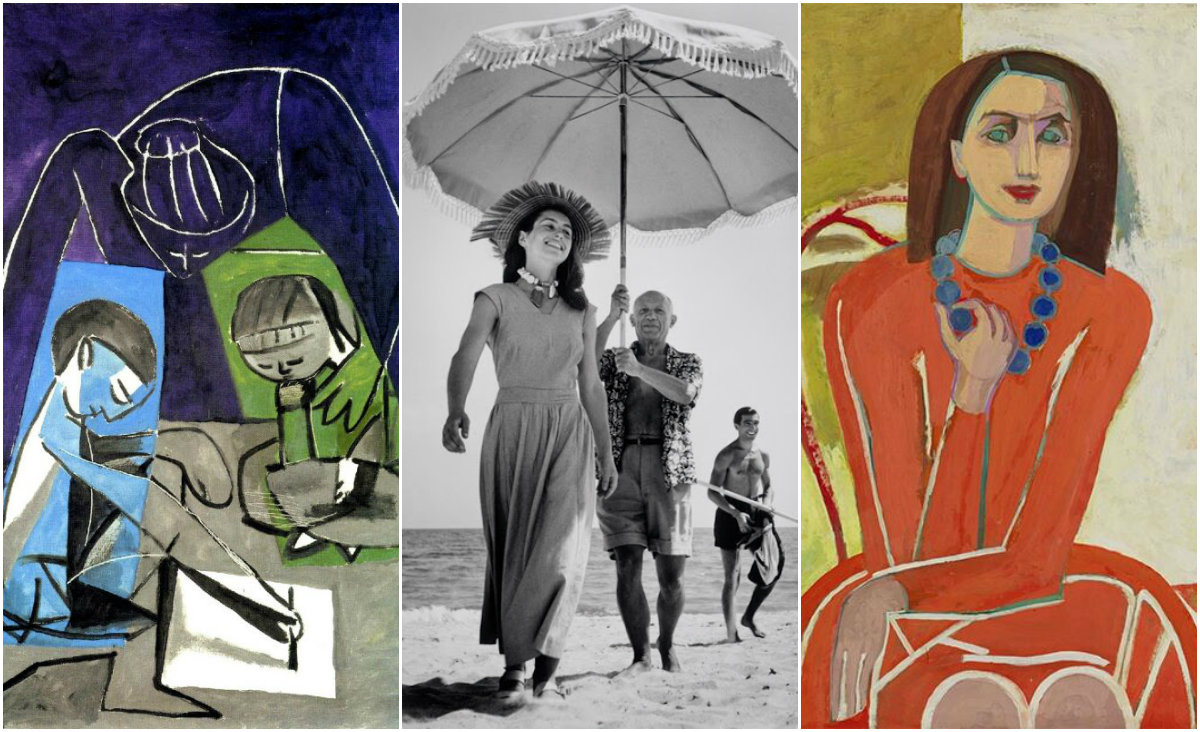

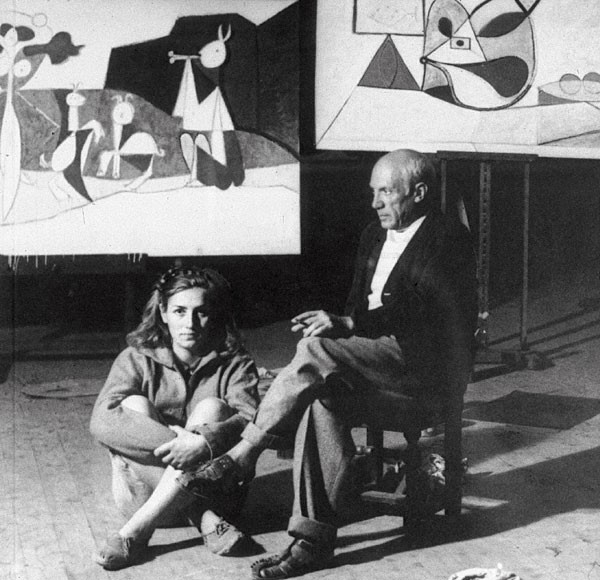

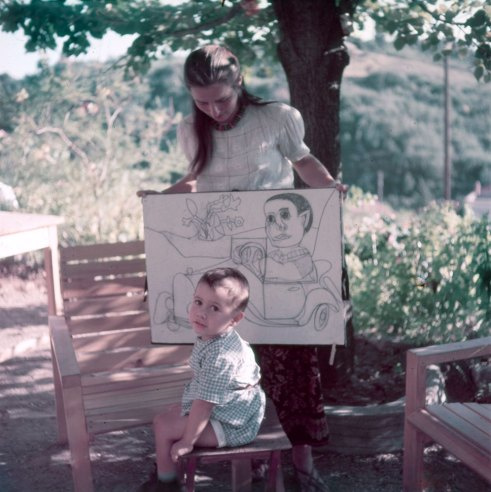

Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot.

1946 photo. Photo source

1946 photo. Photo source

Her oppressive dad Émile dreamed of seeing his only child as a lawyer, besides, he always dreamed of a son… He made Françoise go in for sports, he took her to summer sailing trips, and in winter they went hunting. At the insistence of her father, Françoise was even forced to write with her right hand — as a result, Gilot became ambidextrous. Émile chose books for her, supervised her home education, so by the age of six, the girl already knew Greek mythology perfectly. He made her daughter fearless, firm and purposeful, which she showed her father a little later.

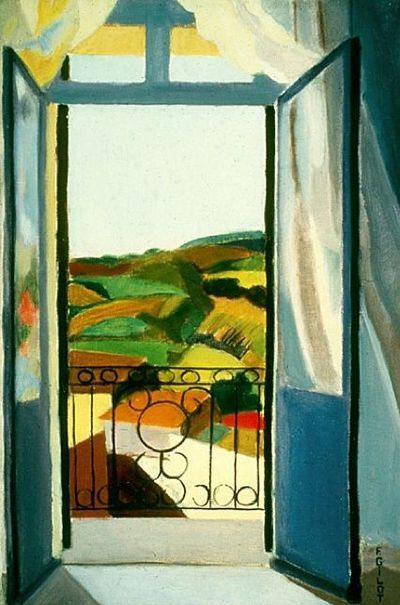

Françoise Gilot. French window in blue. 1939

Gilot studied at the Sorbonne, earned a Bachelor of Philosophy from the British Institute in Paris and a Bachelor of Science in English Literature from Cambridge. But then the parent’s plan misfired: in 1939, her father sent Françoise to law school in Rennes, but she scandalized and failed the oral exam in law, although she passed the written exam. The stubborn girl finally left her studies to devote her life to art, in which she felt support from her close childhood friend, artist Geneviève Aliquot, as well as her mother and grandmother.

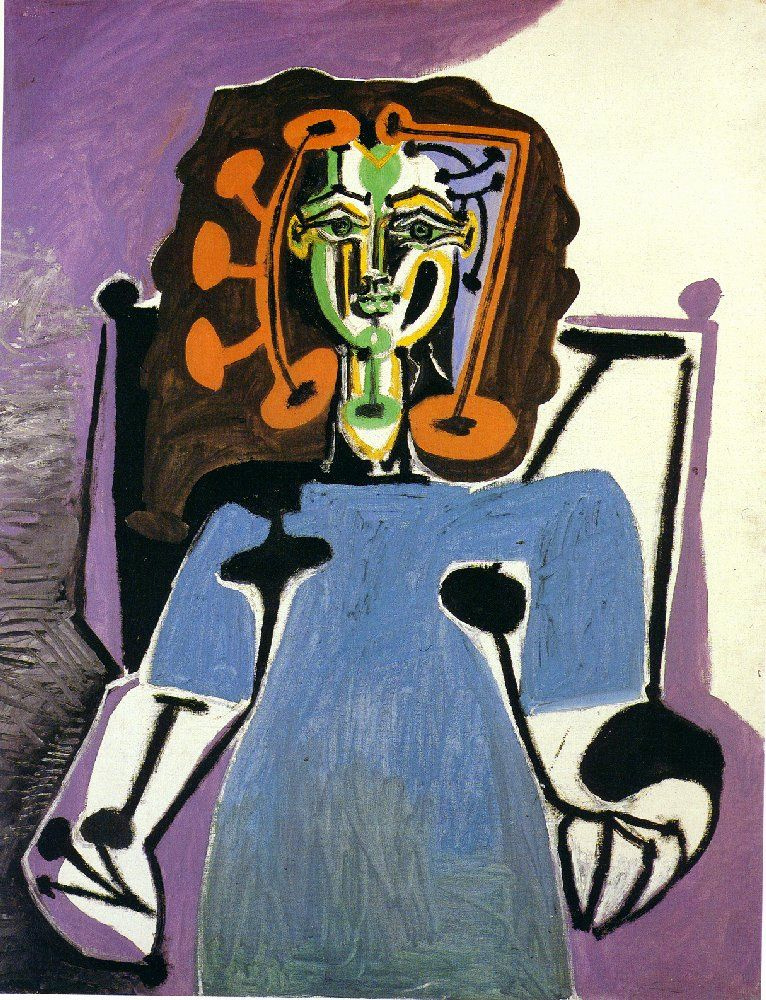

Portrait of Genevieve in white

1944, 35.2×27.1 cm

Françoise grew up in Spartan conditions, therefore she did not attach much importance to her appearance until the age of fifteen, partly indulging her father, who always wanted a son. Her friend Geneviève, who shared the girl’s passion for art, nicknamed Françoise a "page". However, as their mutual friend, the artist Claude Bleynie, wrote, "…together … they exuded a certain mystical energy: Françoise, more active, lively, with a sharp voice and dashing temperament, and Geneviève, much more feminine, and more harmonious physically and spiritually." Geneviève studied with Aristide Maillol, and Françoise was taught by Hungarian Endre Rozsda, who moved to Paris in 1938. Rozsda was friends with Max Ernst and Giacometti, Maria da Silva and Picasso, he taught Françoise the understanding of abstractionism. Nevertheless, Picasso’s Guernica did not impress the girls — both considered it a political gesture rather than a great work of art.

Françoise Gilot. Self-portrait (Figure in the Wind). 1944

During World War II, the Gilot family remained in occupied Paris. Françoise was deeply saddened when her early works were destroyed during a bombing — a bomb hit the truck with family belongings that her father wanted to take out of the capital. However, youth took its toll: together with Geneviève, they continued to paint, dreamed of their own exhibition and anxiously watched what was happening — many of their friends becane members of the Resistance. In 1943, Gilot’s father helped his daughter’s teacher, Endre Rozsda, to draw up documents for returning to his homeland, to Hungary, as he flatly refused to indicate his Jewish origin by wearing the yellow Star of David and could fall into the clutches of the Gestapo. It was Rozsda who uttered the prophetic words at parting at the Gare de l’Est in Paris. "What will happen next, Endre, what will happen?" shouted Geneviève towards the departing train. "Don't worry about it," Rozsda replied. "Perhaps, in three months you will meet Picasso." And so it happened.

Françoise Gilot. Study

for a self-portrait in an orange dress with a blue necklace. 1944—1945

Many years later, Françoise did not hesitate to call her former idol Bluebeard, describing ten years of her life in sufficient detail in her memoir book "Life with Picasso". Despite injunctions and a war of lawyers, the book was published in 1964, revealing a far from ideal image of the famous artist to the world. The book was written very skillfully — no wonder that Françoise received a Bachelor’s degree in English literature.

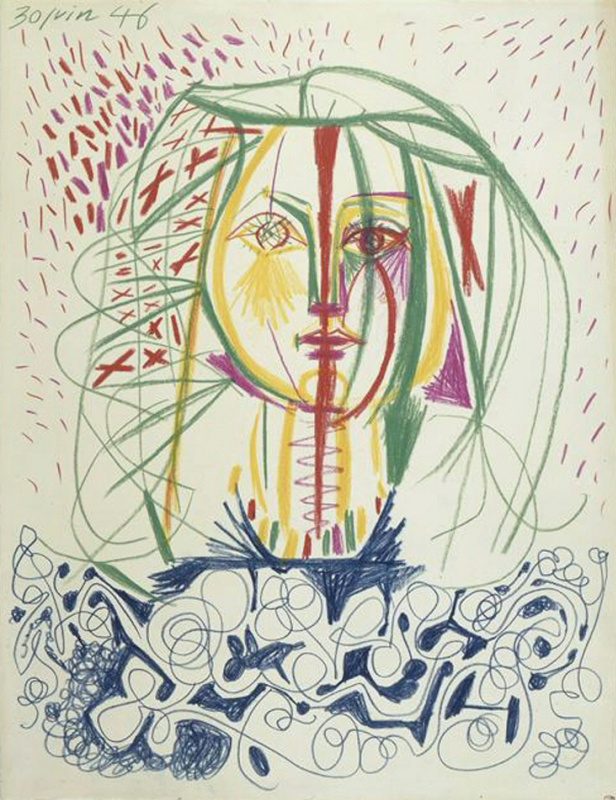

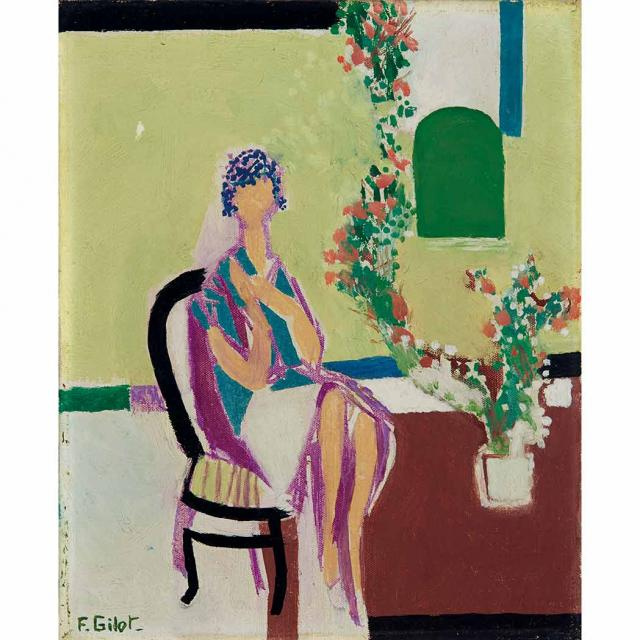

Portrait of Francoise

1946, 66.5×50.8 cm

A fleeting meeting in a café, an invitation to "stop by to see the paintings", and Françoise with her constant companion Geneviève is in the holy place, in the studio of the famous artist. That time, the meeting ended in embarrassment: Picasso showed them his apartment, but when they requested to admire his paintings, he recommended them to go to the museum. "Come because you like me, you are interested in my society, because you want direct, simple relationship with me," Picasso said at the end. The girls interested him — he went to an exhibition of their works, and at the next meeting — who would refuse a visit to Picasso? — he noted in their conversation the undoubted talent of the girls. Then there was another visit, and another one…

Geneviève left for the south of France, to her family, and Françoise kept on visiting Picasso, who showed the young artist the unambiguous signs of attention. However, the fire did not flare up then. Picasso always felt the ghost of his beloved "crying woman", Dora Maar behind his back, his beloved and muse, nervous, jealous and capable of making a scene at any moment. Françoise, on the other hand, was open to the relationship, however, despite of Picasso, she was going through a crisis of her life. As she later recalled, at that time, the men around were older than she was, she was disappointed in her peers… The war made everything fleeting, partly frivolous. Many of her friends left the country, many of them died. In this stormy sea of life, art became the meaning of life and salvation for Françoise Gilot.

After a stormy conversation with her father, the young artist moved to her maternal grandmother and got a job — she taught horse riding in the stables in the Bois de Boulogne. There was almost no time left for art, and only in November 1943 she again paid a visit to Picasso. Their acquaintance was renewed, and Françoise became a frequent visitor on la rue des Grandes Augustins. She brought her paintings, listened to the opinion of the artist, who introduced her to new people who mattered to him — Jean Cocteau and Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Mollet, the poet Pierre Reverdy and the publisher Christian Zervos. There Françoise watched Picasso’s regular clashes with the Gestapo, who pestered the Spaniard with their checks. The feelings between the two outstanding personalities grew stronger, and soon they became lovers.

Much later, Gilot recalled the words that Pablo said to her on one of the February days of 1944: "If you want to keep the gloss on the butterfly’s wings, do not touch them. You can not abuse what should bring light into my and your life. Everything else in my life burdens me and obscures the light. Our relationship appears to me as an open window. I want it to remain open."

Time passed. Guided by Picasso, Gilot mastered new artistic techniques; the war gradually came to its end: on 24 August 1944, Paris was liberated from the Germans. Very quickly, Picasso became a national hero rather than a "degenerate" artist persecuted by the Nazis, and life around him got very active. At a large retrospective of Picasso’s work crowds of people wished to see a living legend in his living room. His life companion, Dora Maar, became more and more jealous, feeling the upcoming break. And amid all the bustle, Picasso devoted more and more time to Gilot, and their connection was a kind of test — Picasso tested Françoise's strength with his antics, but she was quite tough-skinned. Gilot could disappear for a week or two, denying the fate of a martyr woman. And she had someone to look at: Picasso’s wife, Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, the mother of Picasso’s daughter Maya, Dora Maar, who was gradually losing her mind from the escaping love… Sometimes Picasso and Françoise did not see each other for months, living their own lives…

The period of the "Weeping Women" and Dora Maar has ended — Picasso cherished his future Muse, his "flower woman". For all that, "we perfectly got along," Gilot recalled, "there were no particular disagreements between us, partly, probably, because I had not yet touched the ground; I seemed to be floating in the air."

Françoise Gilot with a gladiolus flower. 1949. Photo by Gillon Mily

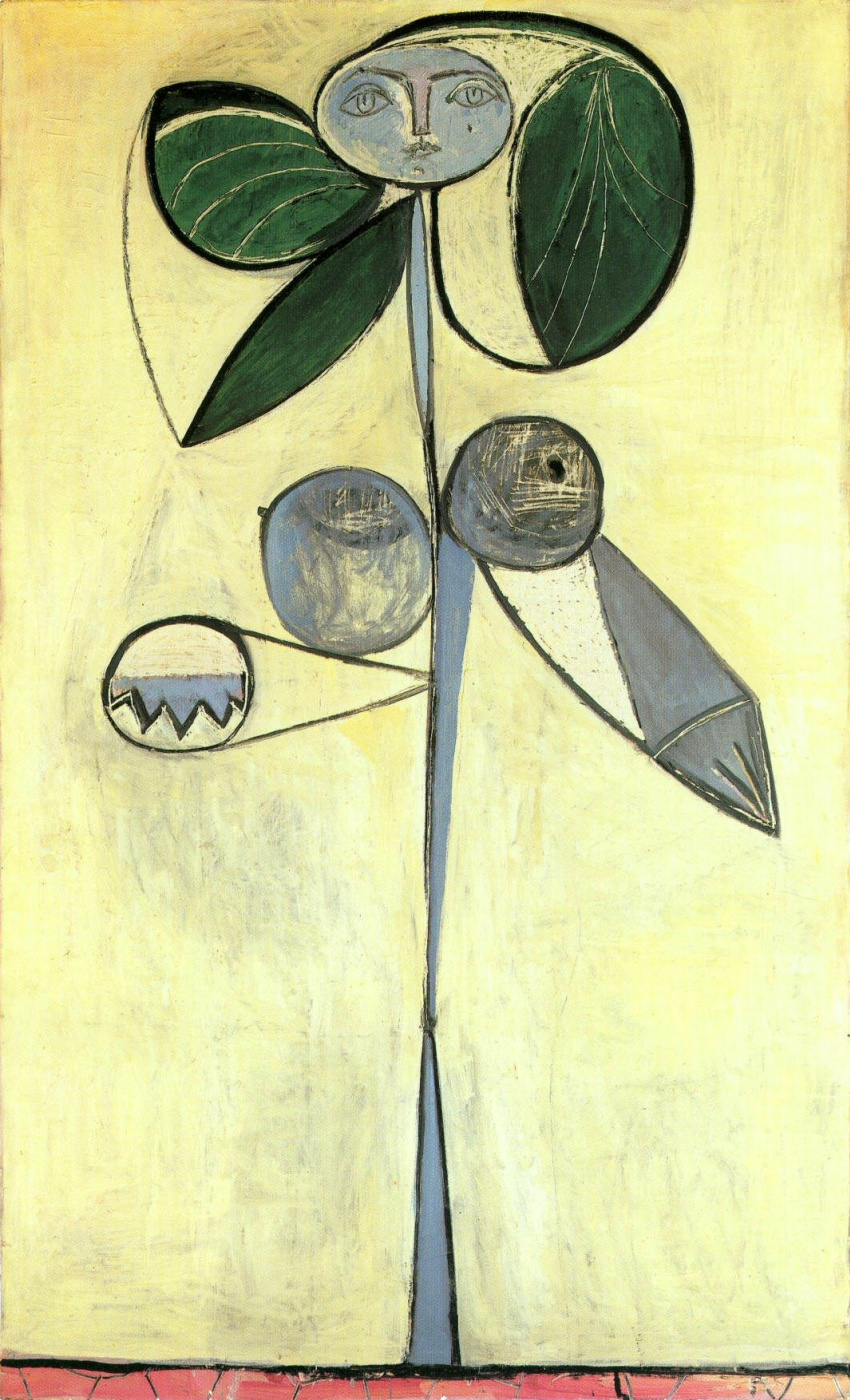

Gilot moved to Picasso in May 1946. For the first month, she virtually did not leave the house, spending all the time in Pablo’s workshop. Picasso was working at the Françoise's portrait Woman-Flower then. He painted and at the same time gave her lessons in composition, explained the principles of his work, which Gilot absorbed and remembered for a lifetime. "I paint pictures like others do autobiographies. Completed or not, they are pages of my diary and in this sense are valuable. The future will select those that it finds preferable," said the artist, starting another portrait of his Muse.

The woman-a flower. Françoise Gilot

1946, 146×89 cm

Françoise's life with Picasso was full of sharp edges that could lead any woman to despair. He took her to live in the house that he once gave to Dora, every morning he read aloud the letters from Marie-Thérèse… The attempt to get away from Pablo failed — Picasso was insistent in his intention to live with Françoise happily ever after, and he offered to seal their bonds by having a child… He succeeded in persuading Gilot, and they left for Antibes, to the sunny empty beaches of the Mediterranean. There Picasso designed the local museum; the friends came — Paul Éluard with his wife Nusch, the poet André Breton. The old friends and rivals of Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse entered the life of Gilot. Her responsibilities were supplemented by maintaining the bank accounts, which Picasso did not trust to his secretary Sabartés. Constant mood swings, morning health complaints, discussion of all former life partners — Françoise was never "bored". And in November it became clear that she was pregnant.

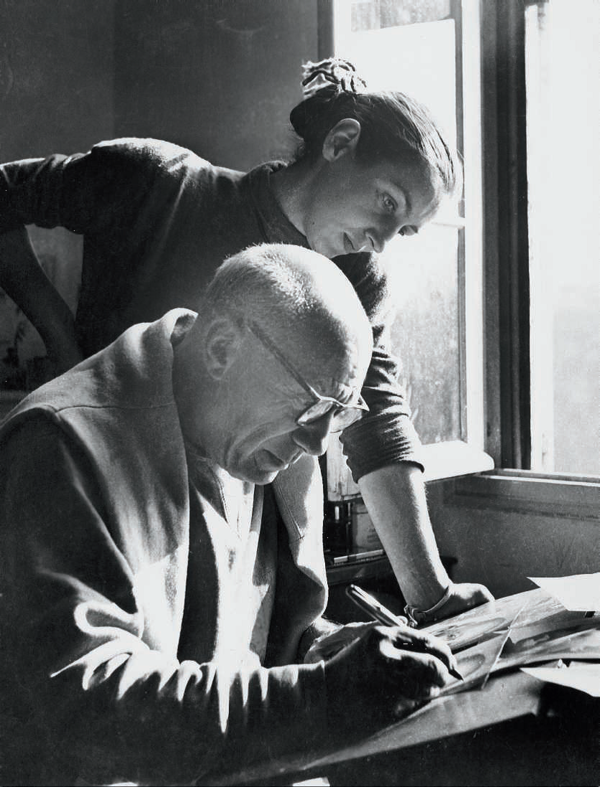

Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot. The artist’s nephew, Javier Vilató, in the background. 1948

Photo by Robert Capa. Photo Source.

Photo by Robert Capa. Photo Source.

Claude Pierre Paul Gilot was born on 15 May 1947. A month later, the family went to the seaside, to Golfe-Juan. Françoise learned to be a mother, Pablo showed his bad character and at the same time was very glad that he tied his beloved to him. He called her "the woman" and did what he had demonstrated more than once — he tried to push his companion away. However, he was angry — she laughed, raised her son, did his business, sent cheques to his ex-wives. The stormy life of Picasso also hurt Françoise: his wife, Olga Khokhlova, came to Antibes and occasionally caused scandals by coming to the beach where Picasso was vacationing with his new family. During this period, Picasso became interested in ceramics: he abandoned painting for a while and devoted himself entirely to working with clay.

In May 1948, the family moved to the small house La Goloise in Vallauris. Françoise finally set up her own workshop, where she could work several hours a day. Guests often came, Françoise and Picasso also drove out — the constant Marseille, who had been serving with Pablo for many years, was driving. Gilot made friends of her own — Picasso’s nephew, artist Javier Vilató, and his girlfriend, Greek Matsie Hadjilazaros.

Pablo Picasso and Françoise Gilot. 1950

Photo by Michel Mako. Photo source.

In April 1949, a month ahead of schedule, Anne Paloma Gilot was born. The family left for Vallauris again. Françoise felt easier with her second child, as she got experienced, but little Claude was jealous of his sister for his mother. The crowds of guests had to be received again. Françoise's health deteriorated, which caused a lot of criticism from Picasso. He often went to Paris, leaving his wife with the children. At first Gilot focused completely on caring for the life of her lover and raising children, trying to please everyone, but over time she began to understand that Picasso was moving away from her again, as it was after the birth of Claude. She did not want to ask him for anything, neither money, which Picasso never gave her, nor help around the house: despicable, bourgeois troubles!

The years passed. Françoise went through the path of becoming a personality, becoming an adult woman, and she did not lack in determination and resilience. Picasso, on the other hand, gradually grew old surrounded by his wife and children, still played with the feelings of others, asserted himself and played off his friends — such was his restless nature. Picasso’s agent, Kahnweiler, offered Françoise a contract for her paintings — she returned to her work and felt that she could provide for herself and the children. And Pablo, meanwhile, was carried away by communist ideas, rode to Paris to his next mistress and rejoiced at the new works by Françoise in between — illustrations for books of poems by Éluard and Verde. Rumors of Picasso’s adulteries got leaked to the press, and Françoise did not know what to do — believe or continue being deceived. She demanded the truth — he denied everything. And this categorical reluctance to tell the truth eventually became a sip of a sobering drink for Gilot. She realized that her relationship with Pablo was at an impasse, only lies and loss of self-respect were forward.

Nevertheless, after Picasso’s 70th birthday, Françoise returned to Paris with him. She worked a lot for the exhibition at the Kahnweiler gallery and tried to ignore … no, not the genius, the grumpy old man tormented by rheumatism. The exhibition opened on 1 April 1952 and it was a great success. Upon her return to Vallauris, Françoise plunged into work again, which protected her from the barbs of her husband, who was distancing himself from the friends who had their own opinion about the paths in art. The death of Paul Éluard horrified Picasso, and he broke bad, as if trying to keep his life, proving to himself that he is still able to do much. In Vallauris, he had an affair with a pretty pottery saleswoman, Jacqueline Roque. In Paris, another lady of the heart was waiting for him, Geneviève Laporte.

The final breakup between Françoise and Picasso happened in the autumn of 1953: she took her children and went to Paris.

After 60 years of work, Françoise Gilot, who turned 98 on 26 November 2019, continues to conquer the world with her paintings. Her works have entered the permanent collections of the Picasso Museum in Antibes, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Tel Aviv Museum, the Museum of Modern Art in Paris and others. In 1990, she received the Knight Commander of the Legion of Honour, the highest honour of the French government, for her work as an artist, writer and champion of women’s rights.