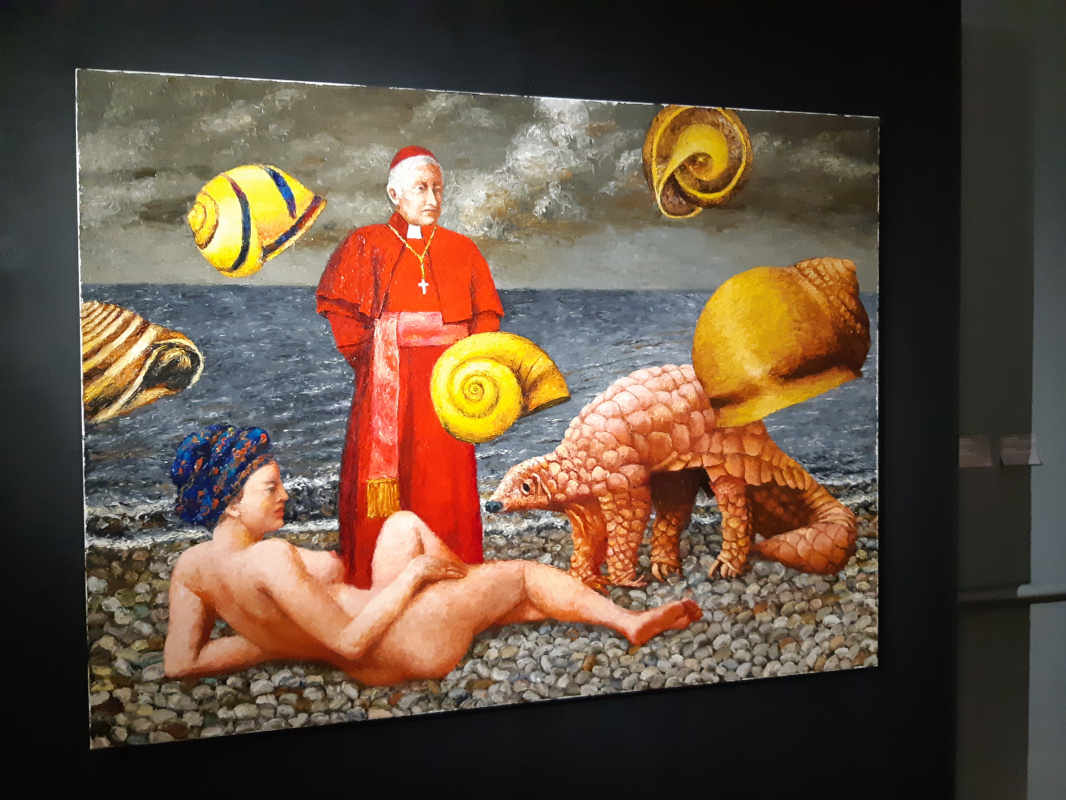

'Aphrodite from Pergamum' (1992) by Valery Koshlyakov. Sale price: £ 14,900 (Sotheby's, 2008). Via kulturologia.ru

2. Materials. It all began at markets, where all the plunder used to be sold. Back in those days art and jewellery were the same market: this is made of gold, this — of copper; this has precious stones in, this is just pretty looking glass. But even today materials matter. An artist’s oil painting will always cost more than his or her drawing. Works by Moldovan artists Gutsu, bought at "Salt" were recently stopped at the Montenegrin border. The argument was that an oil painting could not cost so little. However the artist was selling works cheap because of the pandemic. Paintings are valued highly because we know works, created using the technology, that are 500 years old. Valera Koshlyakov, big artist, living in Paris, had a period in his career, when he used sellotape in his work (and torn cardboard as support). But sellotape looses it’s visual qualities after 15−25 years. As a result a museum curator wants to buy something, and a museum conservator doesn’t allow it.

4. Catholic Church, having been the main and most powerful commissioner of miles worth of painting, created an average "price tag" based on the size and number of images of human figures. By the way, in the Soviet Union, Art Fund rates were very similar to church pricing — multi-figure compositions were priced by the number of heads.

5. The author. Artists first started signing their works in the 8th century. This was the start of the art market of "brands", which was introduced to other markets a lot later. Thus in a sense, art market is a trendsetter. The artist’s name became a collective and universal criterion for price. The artist’s name became the price. Incidentally, this is why those against commercialisation of art are calling for anonymity. Name is the most reliable criterion. Though people age, fall into dementia, or self-repeat. And then everyone start looking for the "early", for example, early Konchalovsky.

7. Relevance. This one is more difficult than novelty, but not by much. I have extensively covered this when writing about museums, but in the era of absence of clear movements and trends, postmodern "tolerance" to all languages and artistic views, it is becoming increasingly important to resonate with what is shown in contemporary art museums. It’s what the subject of debate at Documenta is and the motto at the Venice Biennale.

8. Number of works on the market. This is seemingly clear — the less works, the more expensive they are. But this only applies to the most famous artists. For mid-career and emerging artists, it’s the opposite: the more works there are, the more successful the artist will be, and therefore more expensive. Every new collector (or museum), who buys the work, in a way becomes an advertising agent of the artist.

1. Artefacts market. It’s a marketplace for traditional art, touristy art crafts in museum shops, unlimited editions of famous artists and works by beginners. Pricing here defies analysis. On the one hand, it’s a commodity market and outgoings here are important (materials or working hours). On the other hand, these are prices for services, not unlike restaurant prices: more expensive in tourist areas, and a lot cheaper in bulk. It is important for artists to know that this market does not affect anything, and for buyers — that this is never an investment.

2. Salon. This is the broadest market. This is the art that decorates apartments, offices, hotels and so on. The salon surely focuses on relevance, but with a bit of a delay. Prices here correspond directly to the economic situation in the country. Average prices can be easily calculated based on average property prices or high-quality repairs costs, as this market is closely connected to the real estate market. For example, huge interest toward post-Soviet art among foreigners in the 1990s was due to the fact that our salon works were five time cheaper then, for instance, in Cologne — with more or less same quality. Salon market is important for artists, first of all because, unlike artefact market, it grants an entrance to the professional world of galleries and dealers. One must understand though that prices can only rise here when you move from Kiev to Paris, from Paris to London, from London to Monaco, or wherever else.

‘Disgraced Favorute' (2020) by Oleksandr Roytburd on exhibition "Chronicles of the Plague Year" in the Borys Voznytsky Lviv National Art Gallery. Photo by Olga Potekhina / Artchive.ru

3. Identities market. There is a subject: a country, a city, a subculture. And each subject has a culture. Odessa Museum collects Odessa art, Whitney Museum collects American art. The Ludwig Museum hosts an exhibition of Ukrainian art. Feminist Exhibition, "Italian Transavant-garde". The picture of the subject would not be complete without these artists. They shape it. This market depends on the political situation in the country. For instance, many have recently discovered Ukraine and it is generating a lot of curiosity. The world’s sympathies in the conflict with Russia are on the side of Ukraine. This means it’s high time to self-promote, which in turn means high prices will follow. Diasporas often help at the start. Chinese contemporary art had been bought by New York and Hong Kong Chinese for a long period of time. Italian transavant-garde was brought to New York by gallery owners of Italian origin. The main buyers at the Russian sales in London are immigrants from Russia. However this is not always true — African art, for example, entered the markets not through African Americans, but through French and Belgian markets.

There is one more market, but it stands aside and thus does not fit into any of these hierarchies. Therefore we will place it not in the fifth place, but, for example, the zero place. This is the artistic labour market. It works like any other labour market. This is what it applies to:

• Illustration

• Theatre and cinema

• Art design

• Public art

1. The price is always the cumulative result of communications and efforts by different people: critics, curators, gallery owners, consultants. Make sure that the number of these people does not decrease. Don’t take these roles on yourself, even if you are good at it. If you write well, write articles about other artists; if you want to curate — do not take part in your own exhibitions. The more people are involved in professional activities around you, the closer is the success.

2. Initially the price is governed by the gallery that shows your work. I would make sure that it is no cheaper than a square meter cost of housing. For example, in Montenegro it would be 2 thousand euros for a medium-sized painting.

3. Before you sell 20 pieces in a particular market — agree to discounts. After 20 — raise your prices by 30−50%.

4. To show development, print your first catalog from the second exhibition. Be sure to include works that have already been sold.

5. Take active part in non-commercial projects, especially those with a production budget. Big careers (and hence big prices) are created not by galleries, but by museums and non-profit projects. Non-commercial art is expensive art.

7. Expand the geography of your exhibitions whenever possible. Even if this means more expenses and less profitability. All the sorrowful stories in the market are not to do with economic crises, but with the market’s narrowness and localisation.

8. Only take part in charity auctions. Remember that at a regular auction your work is competing against the work of recognised masters, and they are a lot more well known.

9. Be honest. Call copies copies, however it’s always best not to make them at all if there is no need. For instance, if you are 70 and you are putting together a retrospective and can’t get hold of a number of works — you have lost track of them or museums refuse to lend. This is the only situation when copies can be justified.

It’s only at the very start that the art world seems unbounded. Soon you start to realise that everyone is connected. The artist can have a reputation for being crazy, lazy, misanthrope, have an awful temper- all of this will be tolerated for the sake of your talent. But not deceit.

• Works, sold for over $1 mln constitute 64% of market turnover by value, but only 1% of individual transactions.

• Works, sold for less than $50 thousand constitute 3% of market turnover by value, but 92% of individual transactions.

• 65% turnover of auction sales comes from only 1% of artists.

Galleries and Fairs:

Over 150 000 — number of commercial galleries in the world.

7500 — number of galleries taking part in fairs regularly. (5%).

3 motivations for buying art:

• 60% of purchases — emotionally bound (desire to possess)

• 25% of purchases — business bound (financial investment)

• 15% of purchases — socially bound (PR)

Art buyers over the last 3 years:

• Private collectors: 68%

• Other art professionals: 7%

• International museums: 6%

• Private organisations: 6%

• Local and national museums: 5%

• Art consultants: 4%

• Interior designers: 3%

About the author. Marat Gelman is a collector, gallerist, and an op-ed columnist. The former Director of Perm Museum of Contemporary Art (PERMM), Russia. The Deputy Director of Channel One (Russia) from June 2002 to February 2004. A political consultant, a co-founder of the Foundation for Effective Politics, and a member of Russia’s Public Chamber (2010−2012 convocation). From 2014 has lived in Montenegro.