Leonardesque is a convenient word known not only by art critics to refer to Leonardo’s followers. However the term bellinesque is much less common, which is strange — after all, almost all Venetian art of the late 15th and early 16th centuries was infected with the Bellini family painting style. An art critic Oksana Sanzharova has made an impressive excursion in support of this thesis.

Are bellinesques worth a separate term? Certainly. But there is some uncertainty in this definition: it is necessary to clarify which of the three Bellini is imitated by a bellinesque — Jacopo (father), Gentile (presumably the eldest son) or Giovanni (presumably the youngest son).

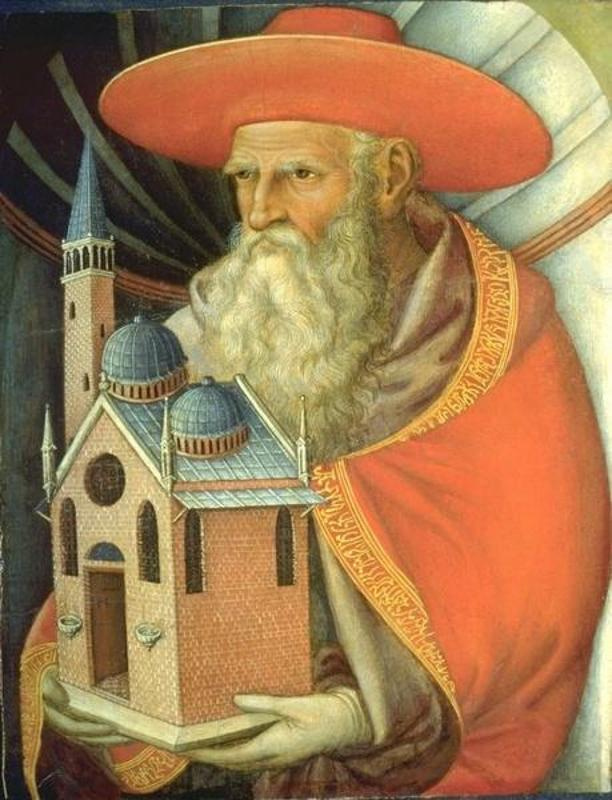

Saint Jerome

1435, 33×25 cm

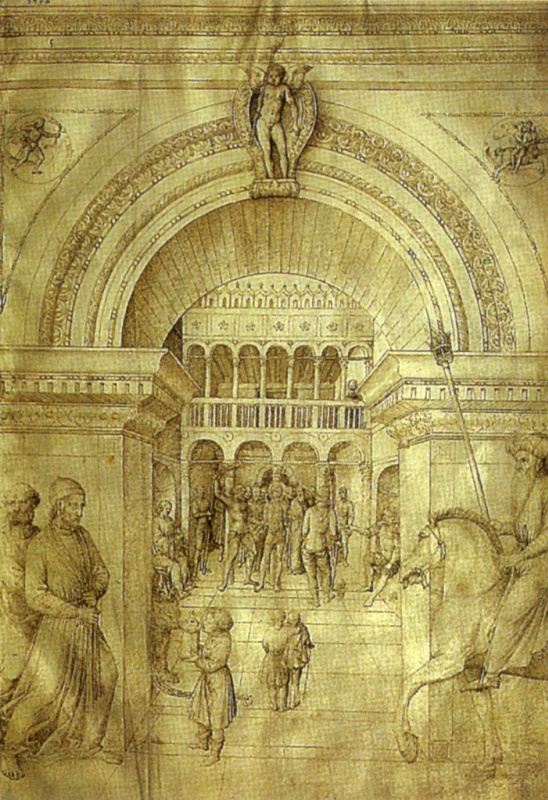

The imitation of Bellini, the eldest, is the most difficult to recognize — after all, very little remains of his painting. However, two albums of his drawings have survived, suggesting that the lost works of Jacopo were not at all as archaic as the surviving ones, that he was interested in perspective, extremely fond of large-scale "urban scenery", and we can see echoes of his passion for rich architectural backgrounds both in the works his son Gentile, and in the paintings of another great Venetian, Vittore Carpaccio.

Much more has survived from the painting of his eldest (presumably) son Gentile, although much of it is lost. The most vivid, most characteristic piece of his heritage is a cycle that tells about the miracles of one of the Venetian relics, the Holy Cross.

Relic of the Holy Cross on the bridge of San Lorenzo in Venice

1500, 323×430 cm

According to Alexandre Benois, in these paintings, Gentile acts as a "wooden and callous realist — rather, even a ‘recorder', who ‘cares little about colourful effects', but ‘marks all kinds of ranks participating in the processions with the greatest zeal, and uses artisanal restraint to paint dignitaries and prelates one portrait (always profile) after another' ."

Benois condemns Gentile for his emotionlessness and lack of psychology, and we are grateful to him for the fragments of 15th century Venice he preserved for us, for the peculiar urbanistic poetry of city walls and roofs, and for his dryish talent that helped a much brighter artist, Vittore Carpaccio, find his style.

Benois condemns Gentile for his emotionlessness and lack of psychology, and we are grateful to him for the fragments of 15th century Venice he preserved for us, for the peculiar urbanistic poetry of city walls and roofs, and for his dryish talent that helped a much brighter artist, Vittore Carpaccio, find his style.

Miracle of the relic of the Holy cross

1496, 389×365 cm

We know Giovanni best of all from the Bellini family; perhaps (but maybe not, the seniority history is quite confusing in this family) the youngest son of Jacopo Bellini.

Speaking of Bellini’s influence they most often mean him.

Giovanni, whom the Venetians called Giambellino, during his long life managed to see the Byzantine canon to be replaced by a passion for antique marbles before it gave place to attempts to copy reality; he saw the dawn of secular portrait and independent landscape; he saw oil replace tempera, and blue and clouds replace chased golden skies. He was not a spectator, he passed through this path with his own brush, changing his technique and styles, keeping only one thing intact: the amazing dreamy mood of his paintings.

Speaking of Bellini’s influence they most often mean him.

Giovanni, whom the Venetians called Giambellino, during his long life managed to see the Byzantine canon to be replaced by a passion for antique marbles before it gave place to attempts to copy reality; he saw the dawn of secular portrait and independent landscape; he saw oil replace tempera, and blue and clouds replace chased golden skies. He was not a spectator, he passed through this path with his own brush, changing his technique and styles, keeping only one thing intact: the amazing dreamy mood of his paintings.

Bernard Bernson wrote about him: "For fifty years led Giovanni Venetian painting from victory to victory. He found it at the moment when it emerged from its Byzantine shell, which was destined to get petrified under the influence of pedantically observed canons, and transferred the most humane art of all the Western world has known since the end of Greco-Roman culture into the hands of Giorgione and Titian."

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano

Perhaps, Cima da Conegliano was one of the most famous and successful bellinesques. The works by the artist are so close to Giovanni Bellini that you sometimes only can distinguish them in museum after you read the signatures.Surprisingly, he most likely did not study directly under Bellini.

However, there is no exact information about his teachers, and little is known about him in general, even his date of birth has only been established approximately.

We know that he was born in Conegliano in 1459—1460, into the family of a well-to-do artisan. He probably got a good education; in his early works, you can find influence of Bartolomeo Montagni, Alvise Vivarini and Antonello da Messina. This allows us to think that either Montagna or Vivarini was his teacher, or he could learn from both.

It is reliably known that since 1492, he lived and worked in Venice for a long time, and by 1500 his workshop had acquired a reputation that allowed the artist to compete with the great Bellini and the slightly less great Carpaccio.

His legacy is polyptychs, triptychs or one-part altarpieces, made according to several well-established patterns, small Madonnas — about 50 of them have survived, several then fashionable half-figured Sacre conversazione (the image of the Madonna with saints), a few separate saints and biblical subjects, and a very little bit of allegories and myths (most likely, decorating coffer chests or cabinet doors).

All this is performed firmly, beautifully and surprisingly evenly — it was not for nothing that Alexandre Benois wrote that "it is almost useless to analyze Cima’s work chronologically, for it is completely homogeneous from its beginning to its end and almost does not undergo any evolution". For his small Madonnas, once and for all took the artist the Giambellino pattern — a half-length or knee-high image against the background of a landscape or curtain with a landscape.

All this is performed firmly, beautifully and surprisingly evenly — it was not for nothing that Alexandre Benois wrote that "it is almost useless to analyze Cima’s work chronologically, for it is completely homogeneous from its beginning to its end and almost does not undergo any evolution". For his small Madonnas, once and for all took the artist the Giambellino pattern — a half-length or knee-high image against the background of a landscape or curtain with a landscape.

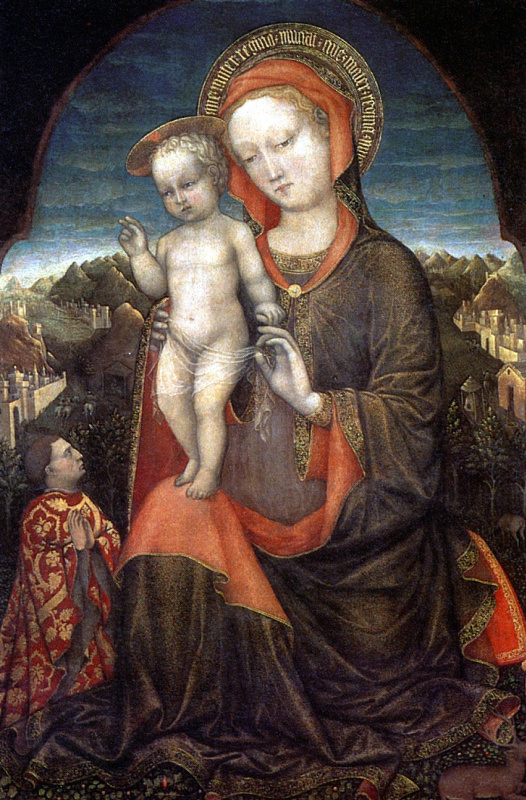

Madonna and Child (Madonna Brera)

1510, 85×115 cm

He also borrows the type of Madonna’s beauty from Bellini, rather sharpens it a little. Perhaps the main difference is the landscape

. And not even the landscape

itself, but the softness brought by the new time, the amazing silvery air, a hint of sfumato, which Bellini’s landscapes are practically devoid of.

Andrea Previtali

Undoubtedly, his not too well-known student, a native of Bergamo, Andrea Previtali, took a lot from Giambellino. Unfortunately, Previtali often replaced Bellini’s calm dreaminess with sentimentality, reaching the point of sugaryness.Another student of Bellini, Sebastiano del Piombo, quickly got rid of the teacher’s influence (mainly due to other influences that he absorbed like a sponge). And yet, "Bellini's features" are present both in his early Madonnas and in his bland "beauties".

Holy interview

1505

Marco Besaiti

The mysterious Marco Besaiti (we do not even know for sure, whether it was one person or two) was also extremely close to Bellini. This artist, not too plain, sometimes clumsy, sometimes very poetic, was especially good at landscapes. They are very close to Giovanni Bellini’s landscape backgrounds, but take on more. There is a feeling that if Besaiti had the opportunity, he would only paint landscapes.Bartolomeo Montagna

Bartolomeo Montagna, an artist from Brescia, took a lot from Bellini (and also from Mantegna and Antonello da Messina).The harsh stony "scenery", in which the painters placed their saints, are particularly similar in Bellini and Montagna’s works.

Vincenzo di Biagio Catena

The explicit influence of the Bellini brothers can be traced in the work by Vincenzo di Biagio Catena. However, looking closely, one can find the influence of Giorgione in Catena (they worked together, which is confirmed by the inscription on the back of Giorgione’s Laura), and Cima da Conegliano, and Antonello da Messina, and even Raphael, whose works Catena saw during his trip to Rome.This artist is archaic and naive in his altar compositions, but convincing and graceful in his portraits, he reminds Gentile Bellini with his senseless drawing and thirst for details.

Giovanni Bellini (studio), The Circumcision, circa 1500, National Gallery, London

Though from Giovanni Bellini took he the characteristic flavour, the rounded dreamy faces of his Madonnas, the favour of lush clouds in the pale blue skies and the general atmosphere of peace radiating from Giambellino’s paintings.

Circumcision of baby Jesus

1500-th

We don’t know much about Catena. Presumably, he was the same age as Giorgione, a wealthy person who began painting quite late and, probably, not so much for the sake of earning as for pleasure. Nevertheless, as an artist, he was quite in demand and enjoyed the patronage of the Doge Leonardo Loredana. He may have had friendly relations with the Bellini family; he made some almost exact copies of Giambellino’s paintings.

Bartolomeo Veneto

Bartolomeo Veneto had many quotes from Bellini. In his life, he quoted many painters, including Leonardo and Dürer.Giorgione, born Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco

It is almost a blasphemy to say "bellinesque" referring to Giorgione, and yet at some stage, he was rather a "bellinesque".

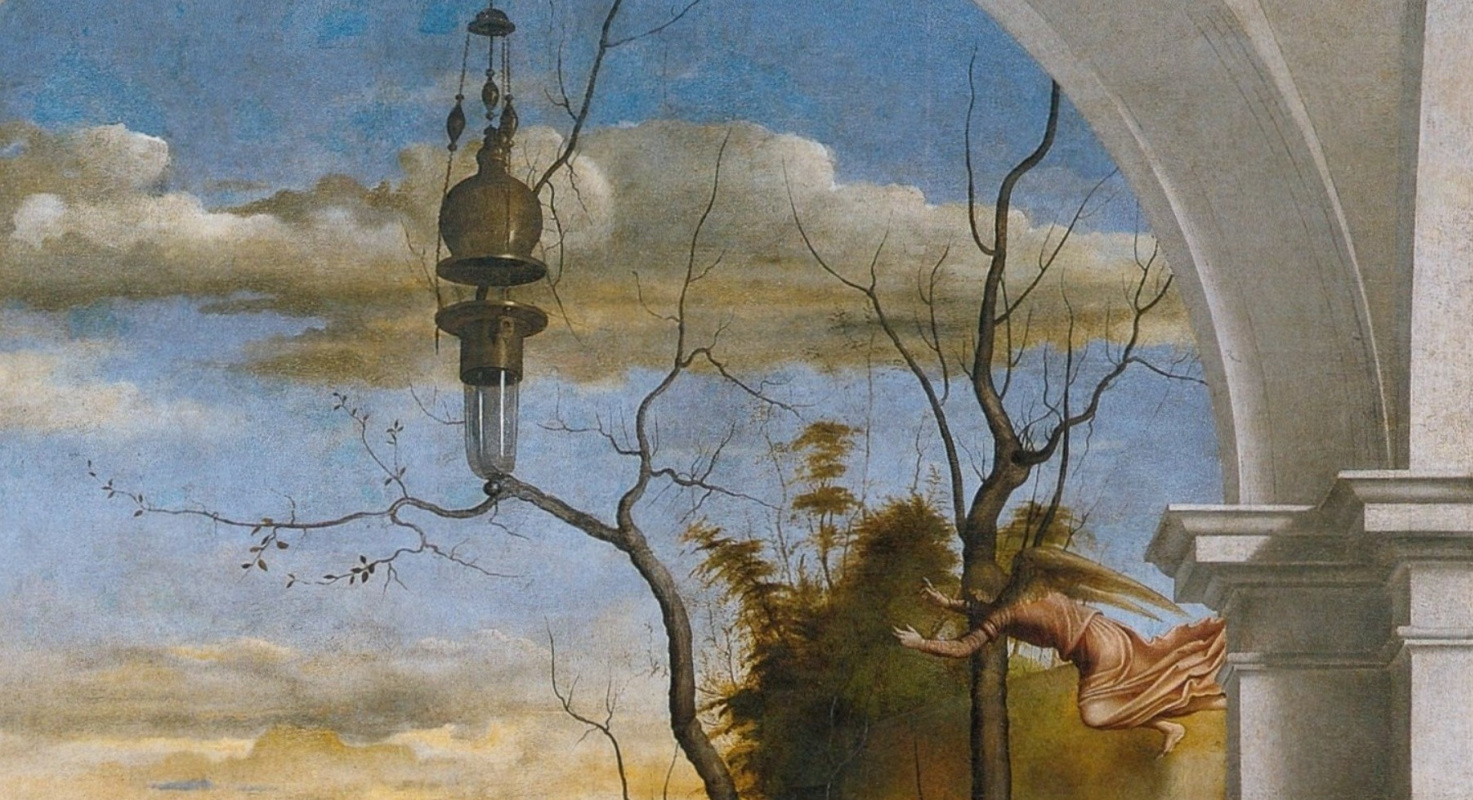

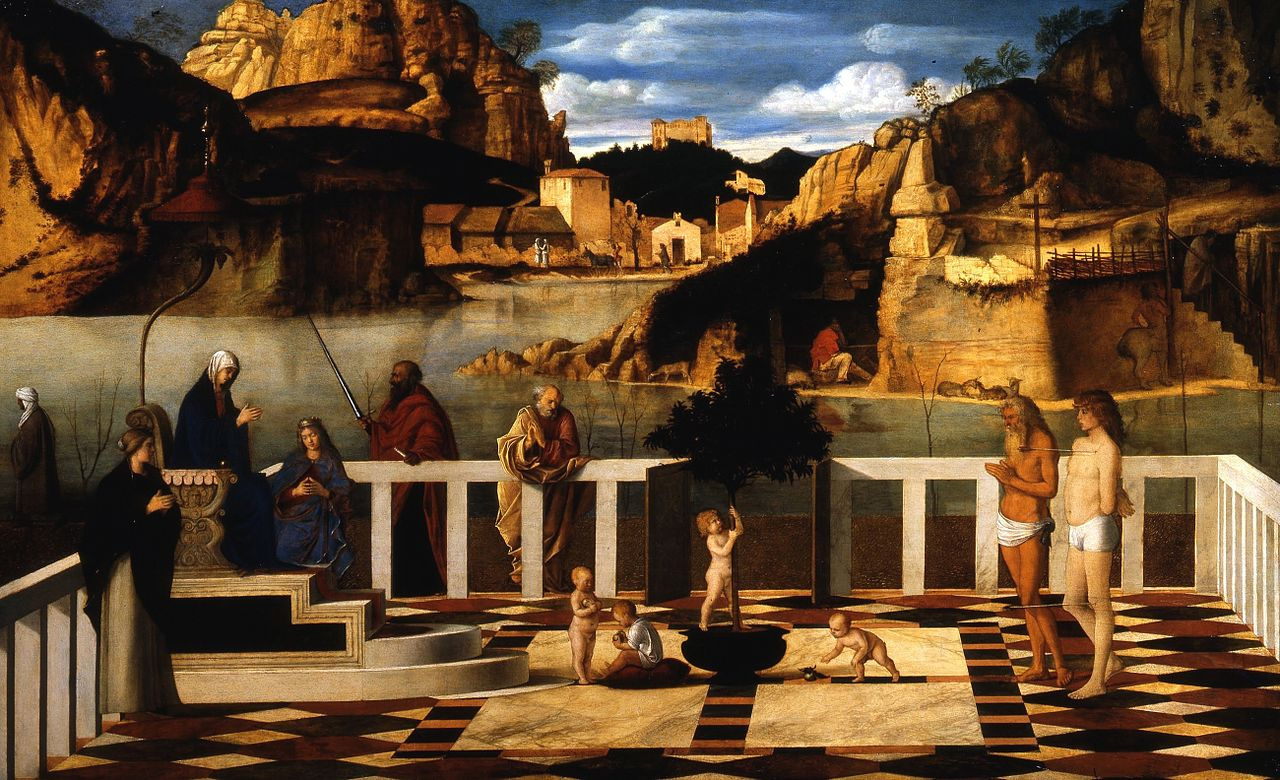

Sacred allegory

1500, 73×119 cm

However, he succeeded in what none of the "leonardesques" managed to do — to overcome his teacher, preserving the most valuable thing of his art: excellent work with light, amazing skill in the landscape

and characteristic drowsy dreaminess.

Lorenzo Lotto

We also find a fair influence of Giovanni Bellini in the early works of another great artist, Lorenzo Lotto.Titian Vecellio

To say that Titian is a kind of a bellinesque is even more sacrilege than to say so about Giorgione. And yet in early Titian, there is quite a lot of imitation of his teacher’s work. Bellini’s features are especially noticeable in Madonnas — particularly, in the Gypsy Madonna with its characteristic pyramidal composition, familiar peaceful landscape and no less familiar golden and green drapery.

Madonna and child (Gypsy Madonna)

1512, 65.5×83.5 cm

His later Madonna of the Cherries has quite a lot from Bellini (and from Giorgione at the same time).

Madonna with cherries

1518, 81.6×100.2 cm

By the way, Titian and Bellini have another common feature that has nothing to do with imitation — they have an amazing ability to changes, incredible flexibility, which allows them to remain the best at any age.