Ботаническая иллюстрация — специфический художественный жанр. Она обладает, казалось бы, несовместимыми качествами: с одной стороны, научная точность, с другой, мастерское живописное исполнение. В исключительных случаях художнику-ботанику удавалось передать в изображении еще и пронзительный восторг первооткрывателя, созерцательное оцепенение перед красотой и совершенством орхидеи, которая цветет раз в 15 лет, или южноамериканского цветущего кустарника, которому только предстояло придумать название.

Когда мир был молод и полон загадок. Когда великие военачальники везли в захватнические походы ученых и художников, чтобы те исследовали завоеванные земли. Когда научные открытия требовали физической выносливости, недюжинной смелости и природной склонности к аванюрным приключениям. В этом мире без фотографии, поездов, самолетов, батискафов естествоиспытатель должен был обладать хотя бы минимальными навыками рисовальщика — чтобы при необходимости зафиксировать впервые встреченный, неизученный мох, бабочку или планктон. В арсенале ученого, снаряженного в заокеанскую экспедицию или находящегося на службе в королевском ботаническом саду, наряду с пинцетом, лупой, скальпелем и альбомом для гербария обязательно были акварельные краски.

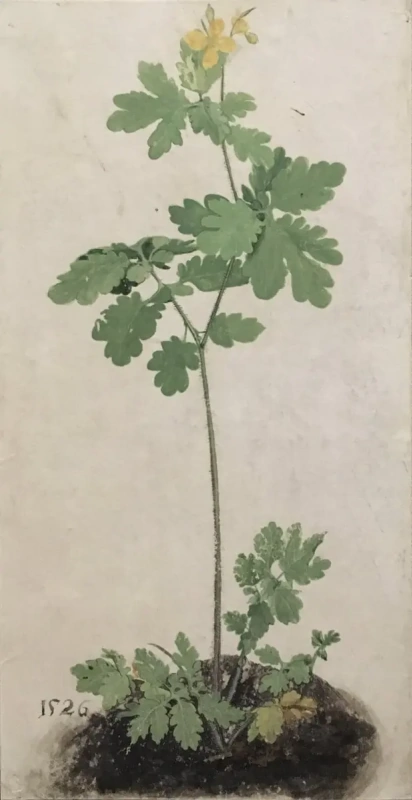

Цветок водосбор

1526

Фармацевтика, наука и реализм

До XVI века европейцам хватало одной-единственной книги о свойствах лекаственных растений. Она была написана в 77 году римским военным врачом Диоскоридом и снабжена иллюстрациями, выполненными с натуры. Книга «О лекарственных веществах» была настолько скрупулезно и обстоятельно составленным травником, что полторы тысячи лет переписывалась, перерисовывалась, обрастала поэтическими вставками, комментариями на разных языках и вполне годилась аптекарю, чтоб тот мог отличить азиатский подорожник от гадючьего лука, отыскать нужное противоядие от укуса змеи или вылечить лихорадку.С началом эпохи Возрождения книга Диоскорида не теряет актуальности (многие известные ботаники будут опираться на нее еще в течение нескольких веков), но мир вокруг сильно меняется: Гуттенберг изобрел печатный станок, на мировой карте появились новые материки и острова, а на них — совсем другая растительность, другая пища, кора и травы, которые неожиданно оказываются панацеей от европейских болезней. Наконец, Земля стала вращаться вокруг Солнца, а не наоборот, а мир начал вращаться вокруг человека. И человек почувствовал свободу в познании мира, ответственность за его изучение.

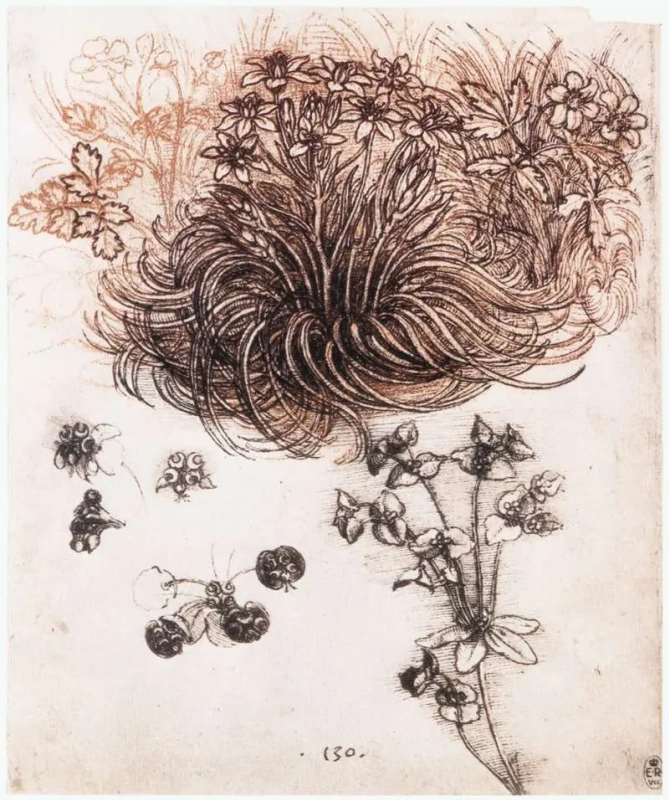

Первыми авторами ботанических иллюстраций становятся художники. Для них точность изображения цветов и деревьев становится настолько же важной, как соблюдение пропорций человеческого тела и знание анатомии. Леонардо да Винчи и Альбрехт Дюрер посвящают ботаническим зарисовкам чуть ли не каждый второй лист в своих альбомах. Как средневековый лекарь знал наизусть названия трав и сверялся при их заготовке с иллюстрациями Диоскорида (к слову, изрядо обезображенными и утерявшими сходство с настоящими растениями в результате бесконечных перерисовок) — так художник Ренессанса в стремлении следовать реальности составляет собственный травник. Впервые — с целью познания, изучения закономерностей и соответствия форм, а не с целью указать верный рецепт лечения.

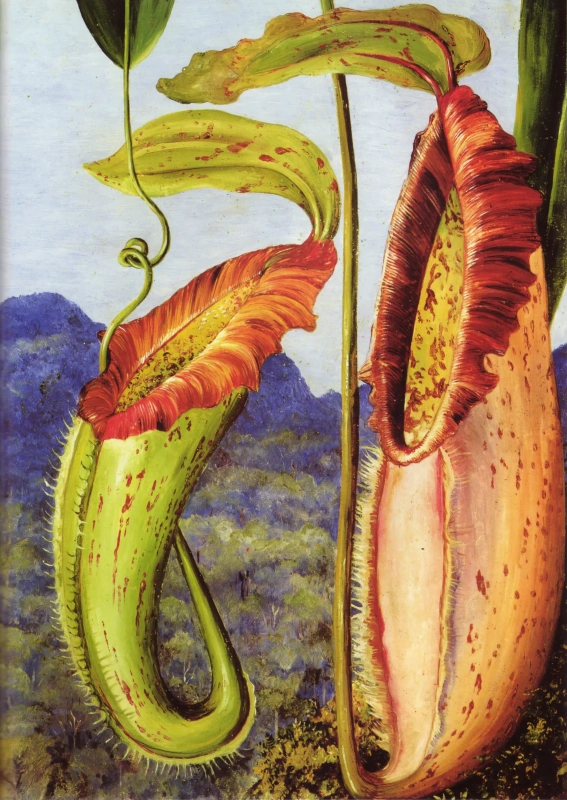

Непентесы (Кувшиночники). «Красота форм в природе»

1904, 32×24.5 см

Корабли и микроскопы

Следующее поколение авторов ботанической иллюстрации — это уже не аптекари и не художники-реалисты. Это поколение ученых. Тех, которые отправлялись в экзотические страны, проводили годы во влажных тропических лесах, мокли под дождями, страдали от морской болезни, возвращались домой с бесценными семенами, аккуратно завернутыми в мох или сухой песок, и с рисунками невиданных раньше растений, насекомых и птиц. Или тех, которые ухаживали за разросшимися королевскими ботаническими садами с оранжереями, редкими видами капризных растений, тщеславными планами превзойти ботаническую коллекцию соседнего монарха. Некоторым из них удалось так близко и пристально вглядеться в божественный замысел, в соответствии с которым организовано все живое в мире, что их акварельные зарисовки и раскрашенные вручную гравюры стали бесконечным вдохновением для многих поколений художников.Мария Сибилла Мериан, например, месяц плыла через Атлантический океан и потом два года жила в Суринаме, нанимала рабов, чтобы те рубили перед ней напролазные заросли. Мериан изучала суринамских насекомых — и стадии их превращения из личинок в бабочек с роскошными крыльями или отвратительных тараканов, которых ее благочестивые европейские соотечественницы именовали не иначе как «дьявольскими тварями». На тот момент ей было уже 52 года — и она успела обучиться живописи и гравюре в мастерской отца и отчима, выйти замуж, сбежать от мужа вместе с детьми, стать успешным самостоятельным предпринимателем и автором нескольких книг о цветах. На дворе был, кстати, XVII век — и на такие научные подвиги решался далеко не каждый ученый-мужчина. А Мериан, естественно, не имела возможности получить образование, художественные материалы были доступны ей исключительно благодаря мужчинам-родственникам, которые могли их приобрести.

Каждого жука, бабочку, ящерицу или гусеницу Мария зарисовывает акварелью в среде его обитания — на удивительных экзотических цветах.

Каждого жука, бабочку, ящерицу или гусеницу Мария зарисовывает акварелью в среде его обитания — на удивительных экзотических цветах.

Пьер-Жозеф Редуте препарировал и изучал растения в Королевских ботанических садах, а заодно зарисовывал коллекцию собранных здесь цветов. Ботаника — сфера, которая не претерпевает изменений от смены политических режимов. Ботаников не казнят вместе с королями и другими придворными. Изучать розы и лилии можно как при монархе, так и при императоре Наполеоне. Поэтому Редуте успешно пережил смену власти. Будучи королевским ботаническим художником, он писал цветочные натюрморты сначала для Марии-Антуанетты, а потом для Жозефины.

Эрнст Геккель — немецкий ученый, который учился на врача, но серьезно раздумывал, не стать ли пейзажистом. К счастью, он стал естествоиспытателем и всю жизнь рассматривал в микроскоп планктон, медуз и стрекающих. В итоге открыл 120 видов одноклеточных и издал книги, которые до сих пор вдохновляют художников и дизайнеров по всему миру. Он побывал на побережьях Сицилии, Египта, Алжира, Италии, на Мадейре и Тенерифе. Геккель умер в 1919 году — и застал эпоху в искусстве, когда изданные им альбомы гравюр вдохновляли художников на полуабстрактные эксперименты и даже архитекторов, которые стремились выстроить здания, в плане напоминающие строение открытых Геккелем медуз.

Книга Эрнста Геккеля «Красота форм в природе» выходила на рубеже веков — 10 альбомов по 10 оттисков. Каждая страница была организована так, чтоб сложная симметричность каждого вида участвовала в общем композиционном совершенстве.

Книга Эрнста Геккеля «Красота форм в природе» выходила на рубеже веков — 10 альбомов по 10 оттисков. Каждая страница была организована так, чтоб сложная симметричность каждого вида участвовала в общем композиционном совершенстве.

Марианна Норт — британская художница, исследовательница, которая путешествовала только в одиночку и не везла с собой деревянных коробок для сбора семян с экзотических растений. 13 лет подряд, отправляясь в путешествия по всему миру, она брала только масляные краски. Дочь богатого землевладельца, она с ужасом думала о браке и называла его «ужасным экспериментом», который превращает женщину в слугу. В отличие от большинства ботаников-профессионалов, Норт писала растения в среде их обитания: крупные экзотические цветы на фоне уникального пейзажа. Такой созерцательный, живописный, способ исследования не помешал Норт открыть несколько неизвестных до сих пор видов растений, в том числе самый крупный плотоядный цветок, который назвали в ее честь — Nepenthes northiana. Пешком забираясь в места, по которым невозможно было проехать, Норт поселялась в лесной хижине и рисовала.

Исследовательница и художница Норт никогда серьезно не училась, взяла только несколько уроков рисования. Но выставка ее работ, которая состоялась в Лондоне в 1879 году, имела оглушительный успех. Пораженная вниманием публики и газетчиков, Норт решила подарить все свои работы Ботаническим садам Кью. Отсроила галерею за свои деньги и по собственному проекту и очень надеялась, что посетителям можно будет подавать чай, кофе и печенье. Директор садов Кью с радостью принял проект галереи, но с негодование отверг идею о чаепитиях. Это, в конце концов, место работы серьезных ученых, а не туристическая достопримечательность.

Картины Марианны Норт — это живописные документы давно исчезнувших мест. Не прошло и нескольких десятков лет, как многие из них были задавлены безжалостными признаками цивилизации: дорогами, магазинами, почтовыми станциями и конторами.

Эти самые известные художники, авторы ботанической иллюстрации, и сотни других формировали особую художественную эстетику, основанную на научной точности и пристальном внимании к самым мелким деталям. Неудивительно, что совсем скоро эта эстетика будет подхвачена уже новыми, авангардными, художественными течениями и стилями.

Исследовательница и художница Норт никогда серьезно не училась, взяла только несколько уроков рисования. Но выставка ее работ, которая состоялась в Лондоне в 1879 году, имела оглушительный успех. Пораженная вниманием публики и газетчиков, Норт решила подарить все свои работы Ботаническим садам Кью. Отсроила галерею за свои деньги и по собственному проекту и очень надеялась, что посетителям можно будет подавать чай, кофе и печенье. Директор садов Кью с радостью принял проект галереи, но с негодование отверг идею о чаепитиях. Это, в конце концов, место работы серьезных ученых, а не туристическая достопримечательность.

Картины Марианны Норт — это живописные документы давно исчезнувших мест. Не прошло и нескольких десятков лет, как многие из них были задавлены безжалостными признаками цивилизации: дорогами, магазинами, почтовыми станциями и конторами.

Эти самые известные художники, авторы ботанической иллюстрации, и сотни других формировали особую художественную эстетику, основанную на научной точности и пристальном внимании к самым мелким деталям. Неудивительно, что совсем скоро эта эстетика будет подхвачена уже новыми, авангардными, художественными течениями и стилями.

Изучение горных пород и папоротников

1843, 29.4×40.6 см

Вспомнить Дюрера и Леонардо

Во второй половине XIX века французская живопись переживает грандиозную революцию — сначала барбизонцы, а потом будущие импрессионисты выходят на пленэры и стремительно пишут впечатление от окружающего пейзажа, световые эффекты. Если соломинок в стоге не рассмотреть — их не нужно прописывать, если роща прячется за туманом — видны только приглушенные цветные пятна, а не миллионы отдельных листьев. Но это лишь центральный, а не единственный путь развития искусства. В то же время французский художник-символист Одилон Редон выпускает сборники литографий с причудливыми растениями, у которых на длинных стеблях покачиваются грустные человеческие головы. И возможно, он не последовал за импрессионистами как раз потому, что главным его учителем был ученый-ботаник, смотритель Ботанического сада в Бордо, Арман Клаво.У Клаво была собственная теория о связях растительного и животного мира, над которой он серьезно работал. Но кроме этой, очевидно повлиявшей на Редона, теории смотритель Ботанического сада Арман Клаво делился с юным художником объемными гербариями и собственными ботаническими иллюстрациями, свежими книгами и соображениями об искусстве. Где-то здесь, в кабинете известного ботаника, Редон открывает собственный художественный принцип: тщательно изучать природу, строение мельчайших живых организмов, чтобы потом, в студии, создавать химер и призраков по обнаруженным законам природы. Мало придумать растение с цветком-головой, нужно дать зрителю почувствовать, как по стеблю от корней движется влага, проникая в сложную систему кровообращения этого существа.

На родине Чарльза Дарвина, во время грандиозных научных открытий в области естественной истории, тоже об импрессионизме речь не шла. В Великобритании самый влиятельный арт-критик — это Джон Рёскин, писатель и художник, который в каждом путешествии делает ботанические и геологические зарисовки и отстаивает точное следование природе. Художники из «Братства прерафаэлитов», которые идеями Рёскина очень вдохновлены, пишут только с натуры — и людей, и природу. Но в отличие от импрессионистов, подсчитывают количество листков и ягод на каждом кустарнике — им не трудно. Чтобы написать Офелию, Милле по несколько часов держит натурщицу в ванне, а чтобы окутать ее правильными цветами, делает натурные зарисовки. Женские фигуры на картинах прерафаэлитов утопают в цветах, причем, определить вид растения и основные его ботанические характеристика не составляет труда. Следовать природе в мельчайших деталях, считают художники, — это единственный путь, способный вывести британское искусство из болота, в котором оно погрязло. Семена, посеянные прерафаэлитами, прорастут тонкими, изогнутыми стеблями, причудливо перевитыми в декоративные узоры, уже скоро, к концу XIX века. В модерне.

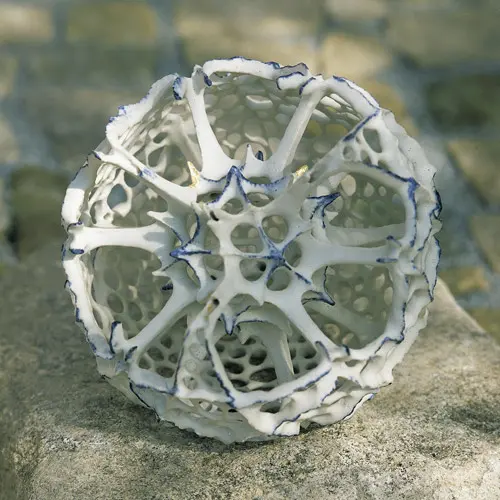

Постботаника, бумага и стекло

В ХХ веке кто угодно может сесть на корабль или на поезд — и отправиться путешествовать, искать счастья и богатства в далеких, беспризорных землях. Все континенты открыты, неисследованных мест остается все меньше. Когда-то дикие леса исхожены, тропы проложены, туземцы надели европейские платья, приняли крещение и научились говорить по-английски. Ботанические атласы сформированы, классификации растений придуманы, невиданные птицы и насекомые изучены. Дело художника — отвоевывать сферы влияния, до которых не добралась промышленная революция, расселять экзотических существ и растительное буйство прямо по домам уставших европейцев. Художники и скульпторы эпохи модерна выбирают растительные мотивы, плавные линии, имитируют выцветшие краски старых изящных ботанических гравюр, раскрашенных акварелью, добавляют золота. Их искусство уже не ограничивается залами галерей — оно проникает в частные дома в виде торшеров, обоев, панно, вычурной мебели.С другой стороны, художники, которые сражаются за новое абстрактное искусство, лишенное сюжетной нагрузки, в восторге листают переизданные книги Эрнста Геккеля — и находят вдохновение и чистое совершенство в причудливом переплетении скелетов одноклеточных. Пауль Клее и Василий Кандинский говорят о серьезном влиянии «Красоты форм в природе» на свои поиски. Клее мечтает когда-нибудь вырастить картину, как растят цветок. Архитектор Хендрик Петрюс Берлаге проектирует здания, в плане повторяющие строение медуз, зарисованных Геккелем. Бесконечные цветы Джорджии О’Киф (1, 2, 3) очень напоминают масляные зарисовки Марианны Норт.

Работы современных художников Kate Kato, Rogan Brown, Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka, Gerhard Lutz. Источники фото: www.kasasagidesign.com, roganbrown.com, www.flickr.com, www. lutz-tonkunst.de

Влияние самых блестящих научных иллюстраций на искусство никогда не прекращалось — и сегодня молодые художники создают скульптуры из металла, керамики, стекла, бумаги под впечатлением от книг ученых-естествоиспытателей, живших 300 лет назад. Тоска по миру, который был молод и полон загадок, жажда открытий и новых знаний ведут их к поискам неожиданных техник и смыслов.

Автор: Анна Сидельникова

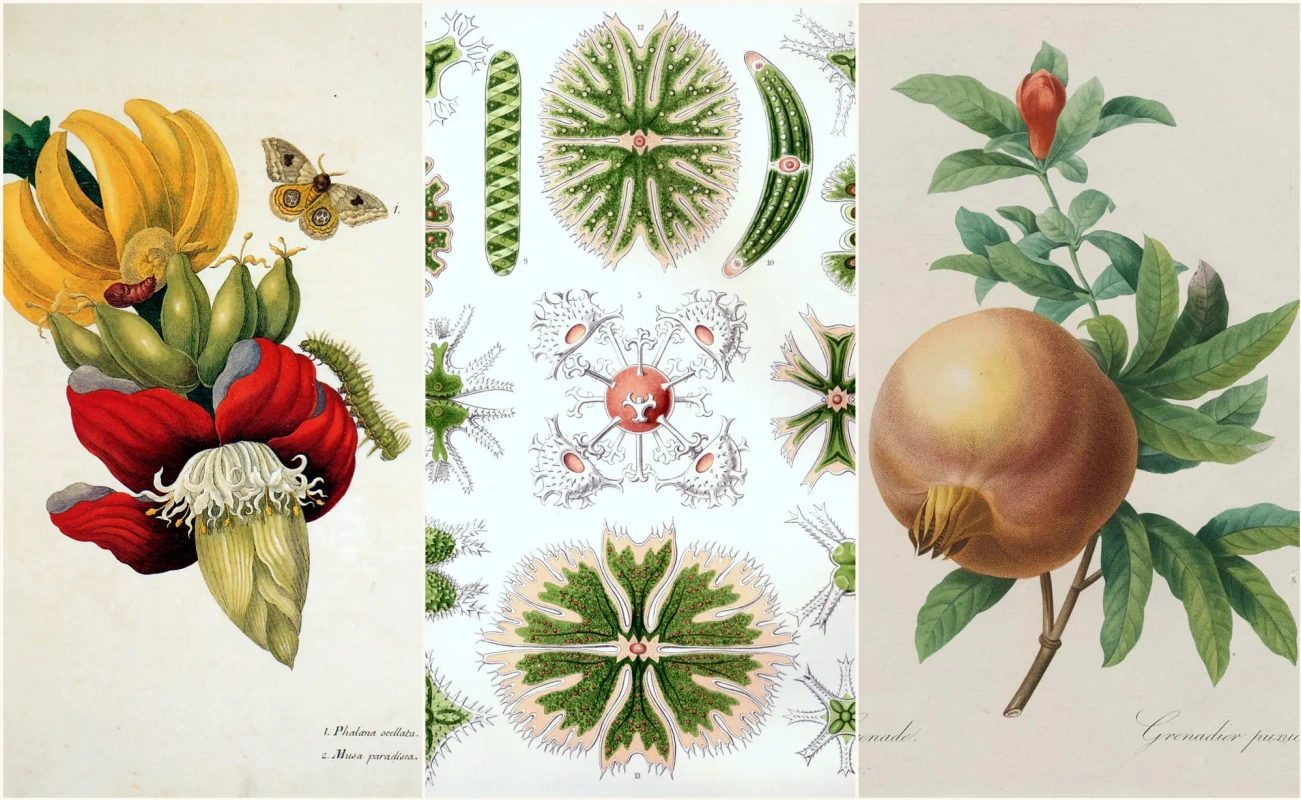

Залавная иллюстрация: Мария Сибилла Мериан, Цветок и плоды банана; Эрнст Геккель, Зеленые водоросли: десмидеи; Пьер-Жозеф Редуте, Гранат.

Автор: Анна Сидельникова

Залавная иллюстрация: Мария Сибилла Мериан, Цветок и плоды банана; Эрнст Геккель, Зеленые водоросли: десмидеи; Пьер-Жозеф Редуте, Гранат.

Артхив: читайте нас в Телеграме и смотрите в Инстаграме