Nothing personal

Minimalism, like most of the postmodernist pioneering styles, arose as a reaction to modernism. Abstract expressionism became its main opponent and the main force to declare war against. The first postmodernists were not satisfied with everything in this movement: extreme emotions, recognizable manners of each artist, artistic charisma and drama, the cult of colour and technology as the quintessence of meanings and deep feelings. Too much spontaneity in the creation process, too much of the artist’s personality in the finished work, too many keys are required for the viewer to understand the subject matter. Instead, minimalists present the viewer with the objective beauty of the object, exclude from the picture context. The viewer may not know and not try to remember the artist’s name, as it doesn’t matter.The "Primary Structures" exhibition raised the issue of the artist’s role: in the press, in the exhibition halls, at the conference held with all participants, they talked about it. Sculptures by minimalists were often made in industrial workshops, and the artist only participated in this process as the author of the sketch, abandoning the technical part, the embodiment.

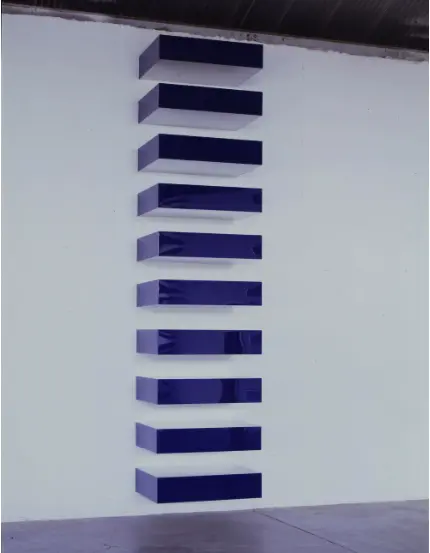

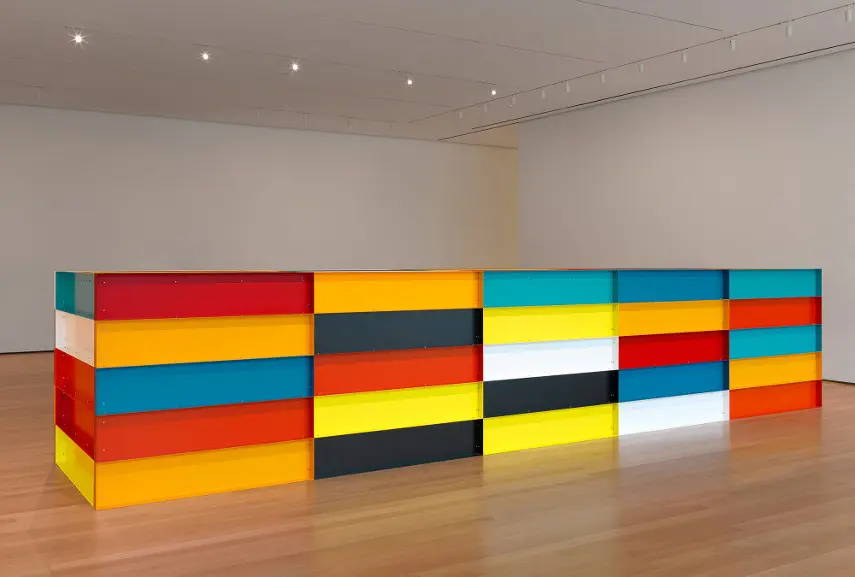

For example, American sculptor Donald Judd designed structures that were difficult to attribute to sculpture or painting in a traditional European artistic context. Judd did not make the rhythmically built right into the showroom wall aluminum and plexiglass bars, but simply gave precise instructions to his contractors. Does the idea of this design make Judd its author, the artist? Even fellow sculptors were not always ready to admit this creative method acceptable.

Nothing extra

The minimalist sculptor and the minimalist artist do not need special professional materials or tools. The special primer of the canvas, the witchcraft of the special oil paint consistency, the frame selection, the choice of varnish, heating the pastels — all these experiments with the techniques that modernists were so fond of became unnecessary and insignificant; moreover, they were declared a hindrance in the search for objective simple beauty. After graduating from university, young Frank Stella worked as a painter, and he created his first famous The Black Paintings series using ordinary interior paint and brushes from a nearby hardware store. Dan Flavin has worked with a single material for 30 years — fluorescent lamps, which were also easy to buy in any home improvement store. Sol LeWitt created 1,350 decorative paintings, all painted with acrylics on walls, being inscribed not only in the particular wall rectangle, but in the architecture of the entire room. At the same time, a whole team of workers often helped him to paint the walls.

Among the main predecessors of minimalism are the artists, sculptors and architects of the German Bauhaus school, the Architectons of Kazimir Malevich, the Vladimir Tatlin's towers. However, all of them were occupied with practicality, utilitarianism, social significance (even speculative, unreal, futuristic) of the created things, whereas the minimalists denied the social and political meanings. Dan Flavin continued to refer to Tatlin in his work for 30 years and created 39 homages to his Monument of the Third International: sculptures made of white fluorescent lamps, resembling outlined architectural structures.

Significant works

Frank Stella was 22 when he started his The Black Paintings series. He had just moved to New York and was, of course, greatly impressed by the work of the Abstract Expressionists. But he took up his own work when he saw Jasper Jones' work. The Black Paintings are huge canvases covered with a single paint, the black one. The geometric pattern of white stripes is just an unpainted canvas. At 23, Stella became famous. Three of his works were on display at the Allen Memorial Museum of Art, and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York the same year. Around the same time, Stella said: "A painting is a flat surface covered with paint, and nothing else".

In fact, any of Dan Flavin’s works claims to be significant, as each of them uses the light and space of the exhibition hall as materials. Flavin created constructions of fluorescent lamps and aluminum building bars. But it could only be considered finished when it was placed on a wall, in a corner, in a niche. It could be a grid of multi-coloured lamps or just one luminous strip placed almost above the floor level. In any case, the sculptural and pictorial meaning of the work became clear in a darkened room, when the light fell on the walls or enveloped the space allotted to it.

Sol LeWitt not only painted walls in museums and public spaces, but also worked extensively with sculpture. His favourite original figure was cube. He explained this passion himself as follows: "The most interesting property of the cube is its relative lack of interest. It is best used as a base unit for any more complex shape." And LeWitt used it: he created many cubic constructions, which were internally divided into many small cubes, he made up several identical initial modules, shifting them relative to their common face.

In 1966, Carl Andre created 8 sculptures for an exhibition at the Tibor de Nagy gallery, and placed them on the floor. Each sculpture consisted of 120 silicate bricks and had a set of similar parameters: the same weight, the same volume, the same height. Only the width and height of the rectangles varied. For Carl Andre, it was important that the sculpture shape the space, and not just take its place in it.

Nothing eternal

Many artists were scolded for the lack of efforts they made to create the artwork. It began about a century before the 1960s, from the Impressionists. And each new avant-garde movement (Cubists, Dadaists, Malevich with his Suprematism, Abstract Expressionists) was accused of the fact that anyone else could paint such a thing. At the same time, the achievements of each trend were recognized sooner or later and engraved into the history of art.Minimalists were the first to question the very importance of such recognition. Their work has become a curator’s nightmare, a challenge to the traditional exhibition organization, a challenge to the traditional system of commercial art evaluation. Often their work was only relevant for a certain room, in a certain lighting, in one curatorial idea. If we take other bricks for Carl Andre’s Equivalents than those used for the first exhibition, would the sculpture lose its value? If you buy a dozen fluorescent lamps in a nearby store and assemble a composition similar to Dan Flavin’s sculptures in your own living room, would this lighting fixture claim to be a work of art? And after all, what about the fact that outside a particular exhibition, a one-time statement, it’s all just lamps and 120 bricks?