log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

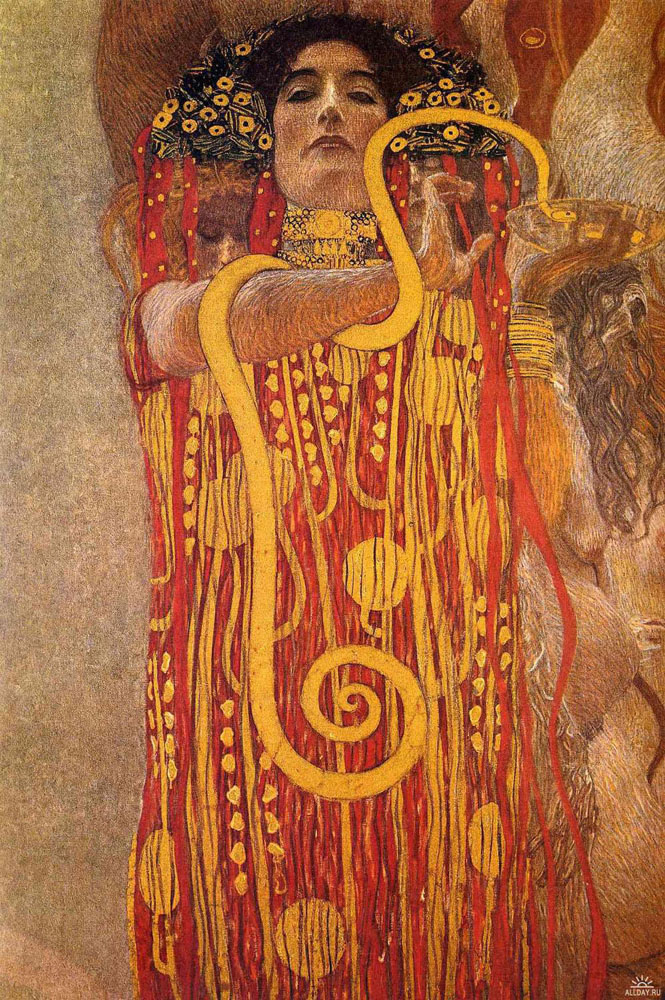

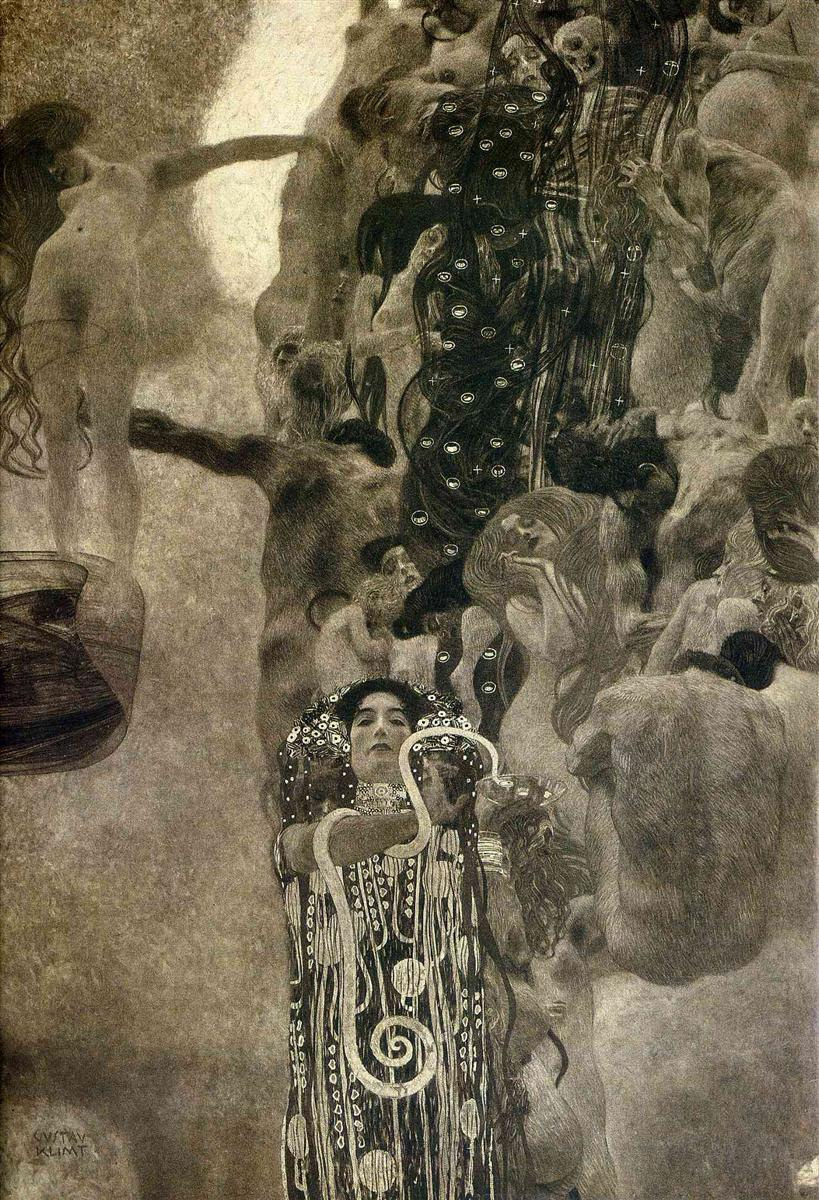

Hygieia. A fragment of the painting "Medicine" (the ceiling Paintings for Vienna University)

Gustav Klimt • Painting, 1901

Description of the artwork «Hygieia. A fragment of the painting "Medicine" (the ceiling Paintings for Vienna University)»

In 1894, Gustav Klimt was an extremely popular artist in Vienna. His colleagues dreamt of the glory that surrounded him. He had painted many successful artworks, caressed by critics, he also managed to make the design for the Burgtheater in Vienna and the Vienna Art History Museum. He was only 26 when he received the Golden Order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria for his contributions to murals painted in the Burgtheater. And in 1894, Gustav Klimt received another prestigious large-scale order: the art committee of the Ministry of Education commissioned him and Franz Matsch to design the ceiling paintings for the assembly hall of the University of Vienna, and approved a budget of 60,000 Guilders (today approximately 400,000 Euros).

The painter was asked to create allegorical renderings of the faculties Medicine, Jurisprudence and Philosophy along with the pendentive paintings.

He first presented his rendering Philosophy at the 6th Secession exhibition in 1900, followed by Medicine at the 10th Secession exhibition in 1901. Both works met fierce criticism and sparked outrage over artist’s departure from the hitherto adhered to historic-conservative painting traditions. Klimt was asked several times to rework his motifs and even rented a second studio with higher walls in Vienna to accommodate the large-scale works. His Faculty Paintings became a political issue. In 1905, the artist refused to deliver the artworks to the Ministry of Education and, aided by his patron August Lederer, paid back his fee of 30,000 Crowns (today approximately 162,000 Euros). It was to be Gustav Klimt’s last public commission.

At first sight, Klimt's Hygieia seems to be put another representation of the femme fatale. Hygieia confronts the viewer almost scornfully, her haughtiness is implied by her upraised chin and inscrutable gaze and her posture is slightly ominous, the golden snake twines sinuously along her upraised arm and it is unclear whether she offering the bowl or withholding it. The stylization of her encompassing red and gold robe serves to hide her body and her hair is covered beneath her rich headdress, the only indication of humanity and feminine sensuality lie in her bare face and arms, and even here, her sensuality becomes a source of power, though she stares out of the painting, her eyes are hidden in shadow. It is clear that Hygieia is powerful and dangerous in her own right.

Hygieia, according to Greek myth, was the goddess of hygiene, of health, cleanliness and sanitation. In fact, the snake and the bowl remain symbols of pharmacy to this day. In this context, she was not a femme fatale but belonged rather in the traditional categorization of women as caretakers. This explanation of Hygieia contrasts with Gustav Klimt's powerful, inscrutable and even ominous depiction of her.

At the same time, it is clear that Hygieia is not the only figure in this artwork, hidden amongst her elaborate headdress are the reposing faces of two women and the bare torso of a naked pregnant woman is partially hidden by Hygieia's red robe. Behind Hygieia, or perhaps within her, are very human very vulnerable women whose downward gazes, flowing hair and nudity speak much more to traditional depictions of women than Hygieia's strange defiance and power. Is she protecting these women? Is she instead threatening such women? Are these women another side of Hygieia, is she both vulnerable and powerful, innocent and mysterious? These questions are swallowed in the inscrutable gaze of Klimt's Hygieia.

The painter was asked to create allegorical renderings of the faculties Medicine, Jurisprudence and Philosophy along with the pendentive paintings.

He first presented his rendering Philosophy at the 6th Secession exhibition in 1900, followed by Medicine at the 10th Secession exhibition in 1901. Both works met fierce criticism and sparked outrage over artist’s departure from the hitherto adhered to historic-conservative painting traditions. Klimt was asked several times to rework his motifs and even rented a second studio with higher walls in Vienna to accommodate the large-scale works. His Faculty Paintings became a political issue. In 1905, the artist refused to deliver the artworks to the Ministry of Education and, aided by his patron August Lederer, paid back his fee of 30,000 Crowns (today approximately 162,000 Euros). It was to be Gustav Klimt’s last public commission.

At first sight, Klimt's Hygieia seems to be put another representation of the femme fatale. Hygieia confronts the viewer almost scornfully, her haughtiness is implied by her upraised chin and inscrutable gaze and her posture is slightly ominous, the golden snake twines sinuously along her upraised arm and it is unclear whether she offering the bowl or withholding it. The stylization of her encompassing red and gold robe serves to hide her body and her hair is covered beneath her rich headdress, the only indication of humanity and feminine sensuality lie in her bare face and arms, and even here, her sensuality becomes a source of power, though she stares out of the painting, her eyes are hidden in shadow. It is clear that Hygieia is powerful and dangerous in her own right.

Hygieia, according to Greek myth, was the goddess of hygiene, of health, cleanliness and sanitation. In fact, the snake and the bowl remain symbols of pharmacy to this day. In this context, she was not a femme fatale but belonged rather in the traditional categorization of women as caretakers. This explanation of Hygieia contrasts with Gustav Klimt's powerful, inscrutable and even ominous depiction of her.

At the same time, it is clear that Hygieia is not the only figure in this artwork, hidden amongst her elaborate headdress are the reposing faces of two women and the bare torso of a naked pregnant woman is partially hidden by Hygieia's red robe. Behind Hygieia, or perhaps within her, are very human very vulnerable women whose downward gazes, flowing hair and nudity speak much more to traditional depictions of women than Hygieia's strange defiance and power. Is she protecting these women? Is she instead threatening such women? Are these women another side of Hygieia, is she both vulnerable and powerful, innocent and mysterious? These questions are swallowed in the inscrutable gaze of Klimt's Hygieia.