Hollywood superstar Leonardo DiCaprio has teamed up with his father to produce a film about Stanisław Szukalski, a half-forgotten Polish artist who died more than 30 years ago.

The new Netflix documentary Struggle tells about talented but obscure Polish artist named Stanislaw Szukalski. Leonardo DiCaprio’s father George was friends with Szukalski.

The film shines a light on Szukalski’s colorful life and the hardships he endured during World War II. Born in Poland in 1893, he moved back and forth between Chicago and his native Poland as a young artist on the rise. By 1934, Poland had declared him the country’s greatest living artist and the Szukalski National Museum in Warsaw was home to most of his intricate paintings and massive sculptures, notable for their dramatic mythological imagery.

The film shines a light on Szukalski’s colorful life and the hardships he endured during World War II. Born in Poland in 1893, he moved back and forth between Chicago and his native Poland as a young artist on the rise. By 1934, Poland had declared him the country’s greatest living artist and the Szukalski National Museum in Warsaw was home to most of his intricate paintings and massive sculptures, notable for their dramatic mythological imagery.

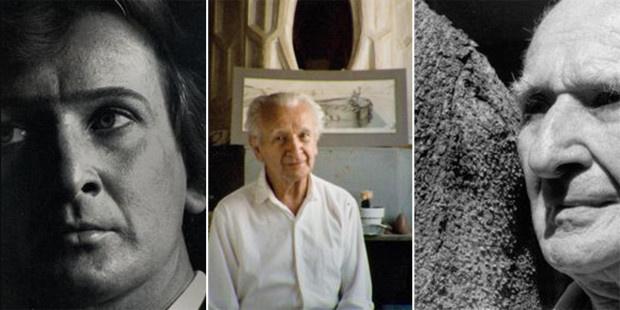

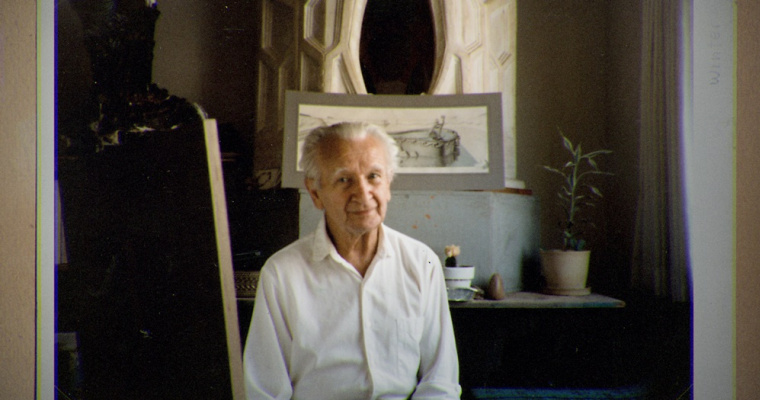

Still from the film Struggle (2018)

"He had an unusual gift of combining many different artistic styles," states Lameński, an art historian at the Catholic University of Lublin and an expert on Szukalski’s art and life. "From Gothic and renaissance

European art, through to contemporary styles like Art Nouveau and Expressionism

, to Pre-Columbian art."

But despite these multi-cultural influences, he was not the least bit cosmopolitan. His aim and ambition was to create purely Polish art, deeply rooted in early Polish folk and pagan traditions. And when he reappeared back in Poland with an exhibition in 1923, he was ready to conquer the Polish art scene.

But despite these multi-cultural influences, he was not the least bit cosmopolitan. His aim and ambition was to create purely Polish art, deeply rooted in early Polish folk and pagan traditions. And when he reappeared back in Poland with an exhibition in 1923, he was ready to conquer the Polish art scene.

George DiCaprio appears throughout the film in interviews while the only reference to Leonardo is a picture of him as a child with Szukalski.

George DiCaprio had used to bring around his young son, Leonardo. One day, Szukalski took the family’s copy of a monograph and added an inscription for the child. "A warning," he jotted down in the front cover of the book. "Please do not grow up too fast."

George DiCaprio had used to bring around his young son, Leonardo. One day, Szukalski took the family’s copy of a monograph and added an inscription for the child. "A warning," he jotted down in the front cover of the book. "Please do not grow up too fast."

Advice that was probably not heeded. But nevertheless, Leonardo DiCaprio, like many others, has remained interested in Szukalski, even long after the artist’s death in 1987. The actor is a noted collector of Szukalski’s sculptures, and contributed funding to a retrospective of his work at the Laguna Art Museum in 2000. Now, he serves as a producer along with his father on the documentary—the work of director Irek Dobrowolski—which tells the story of Szukalski’s troubled life and complicated body of work. The film recently premiered at the Amsterdam Documentary Film Festival, and Netflix intends to make it available worldwide.

Left: Stanislaw Szukalski with a young Leonardo DiCaprio. Source: The First News

Left: Stanislaw Szukalski with a young Leonardo DiCaprio. Source: The First News

Flooded city

1954, 61×71.2 cm

Szukalski’s sculptures and drawings were dramatic, monumental, surreal. The title of the film comes from one of his best known works—a tense, sinewy hand with eagle heads emerging out of the fingertips—but also substitutes for the overarching theme of his life.

Szukalski himself recounts a story from the time his star was on the rise of attracting the notice of a high-ranking Nazi official who asked whether he would be interested in making art for the German government. Needless to say, the drawing he says he submitted depicting Hitler in a tutu was promptly rejected and no further requests were forthcoming.

A major stumbling block, one that is addressed in the documentary and will likely cause further debate, came at the end of filming when the crew happened upon some of Szukalski’s 1930s texts in Polish that suggest he held nationalistic, anti-Semitic views.

In the film, George expresses regret about his friendship with the artist and spoke of being "blindsided," but artist’s friend Glen Bray is convinced that Szukalski was just caught up in the nationalist fervor sweeping Europe at the time, and that his ideologies changed over time.

In the film, George expresses regret about his friendship with the artist and spoke of being "blindsided," but artist’s friend Glen Bray is convinced that Szukalski was just caught up in the nationalist fervor sweeping Europe at the time, and that his ideologies changed over time.

One of Szukalski’s sculptures, inspired by Pre-Columbian art.

Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe (NAC)

The film posits that the closer you look at Szukalski’s artistic output and find out the truth about his backstory, the more you can see their troubling links. The nationalistic undertones of the work and his affinity for mythological megalomania—Szukalski tended to view himself as a god-like figure of the arts—have direct roots in the parts of his life that are intertwined with 20th century fascism.

Based on materials from Artnet, Observer and others.

Title illustration: collage of Szukalski’s photo

Title illustration: collage of Szukalski’s photo