Francis Bacon’s biography is worth being filmed by Quentin Tarantino or Guy Ritchie. What happened to the artist during his usual week, would suffice for a couple of thrillers, five melodramas and one black comedy. So, here we go!

Francis Bacon (photo by John Deakin, 1952)

Bacon had very unique, or even paradoxical ideas about the beautiful. Paired sides of a beef carcass, open mouths, fresh wounds — all this seemed beautiful to him. Bacon was almost genuinely puzzled when his paintings were called scary, violent or shocking. When Margaret Thatcher once referred to him as "that man who paints those dreadful pictures," he was only partly flattered.

In interviews, Bacon often told that at the dawn of his artistic career, during a trip to France, he purchased a book about oral diseases, richly illustrated by hand. And he fell in love with these pictures — with the iridescent overflows of inflammation, the smooth outlines of ulcers and the brilliance of tooth decay. Since then, the mouths hold a special place in his painting. When one of the interviewers remarked: "Francis, most of your mouths are black," he replied: "I had always thought that I would be able to make the mouth with all the beauty of a Monet landscape though I never succeeded in doing so."

In interviews, Bacon often told that at the dawn of his artistic career, during a trip to France, he purchased a book about oral diseases, richly illustrated by hand. And he fell in love with these pictures — with the iridescent overflows of inflammation, the smooth outlines of ulcers and the brilliance of tooth decay. Since then, the mouths hold a special place in his painting. When one of the interviewers remarked: "Francis, most of your mouths are black," he replied: "I had always thought that I would be able to make the mouth with all the beauty of a Monet landscape though I never succeeded in doing so."

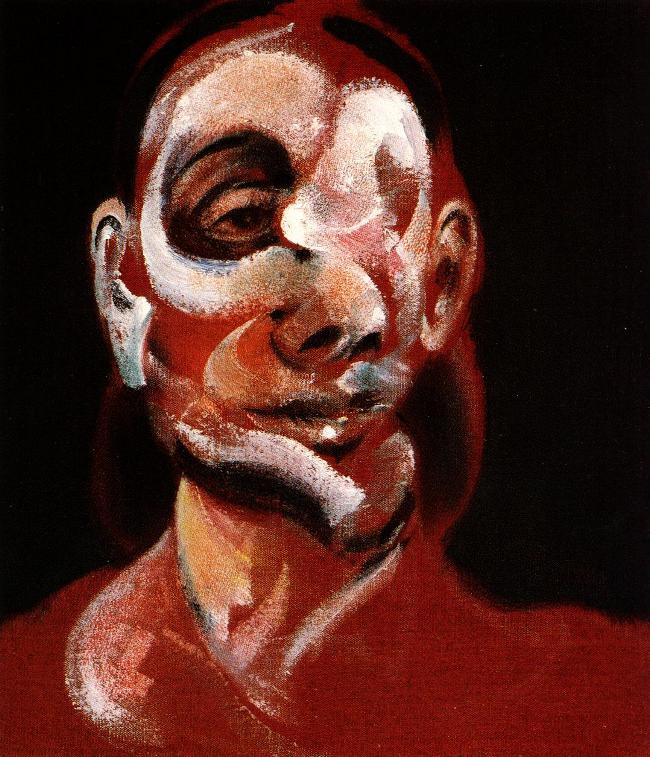

Three studies of Muriel Belcher (fragment)

1989, 152×116 cm

Francis Bacon was served alcohol for free. At least in the pub "Colony Room" in Soho. When he was among those "of great promise", the owner of the "Colony" - Muriel Belcher — offered him a deal. Bacon was supposed to bring his famous friends to the pub, and received 10 pounds a week and free drinks in return. In those days it was a great help for this inveterate drunkard. However, "Colony Room" remained his favourite drinking establishment throughout all his life. He continued going there even after Muriel’s death. Even when he became one of the most important, famous and expensive artists of the world. Even after one of his kidneys was removed.

Jessie Lightfoot (Francis' nanny) with the artist’s sister and brother. 1920. (source: francis-bacon.com)

Bacon’s nanny — Jessie Lightfoot — was an interesting person. Francis lacked his parents' love, and the nanny took care of him since childhood. When the boy grew up, she continued taking care of him. Which still did not prevent her from taking an active part in the ventures which a respectable citizen would consider doubtful. Bacon (under the pseudonym "Francis Lightfoot") placed in "The Times" ads in which he offered gentlemen the services of a "companion", and his nanny was present at the castings. By the '30s, she was practically blind, so she paid more attention to the applicants' wealth rather than their appearance. When Bacon organized a clandestine casino, the nurse Lightfoot did not just get involved in the process — she was the only one who took profit from it. Still, roulette did not clear booze expenses. On the other hand, the old lady invariably received generous tips, getting drunk customers into the restroom. It’s no surprise that Bacon was closer to his nanny Lightfoot than to his own mother.

A shot from the documentary "Francis Bacon" (directed by David Hinton, 1988).

Francis Bacon was a drunken player. He played roulette — a game, which in his own words, gave the player the worst chance. He did not have a system, and liked losing almost as much as winning. When Bacon was asked whether it was typical of him to take risks in his work in the same way he did it while playing, he was surprised: "Is that a risk? The only real risks are physical, when you put your life at risk."

In general, Bacon had a generous nature. After the inheritance of the family estate, many unforgettable evenings in the "Colony Room" began with the words: "Let's blow off what’s left of my trust fund."

In general, Bacon had a generous nature. After the inheritance of the family estate, many unforgettable evenings in the "Colony Room" began with the words: "Let's blow off what’s left of my trust fund."

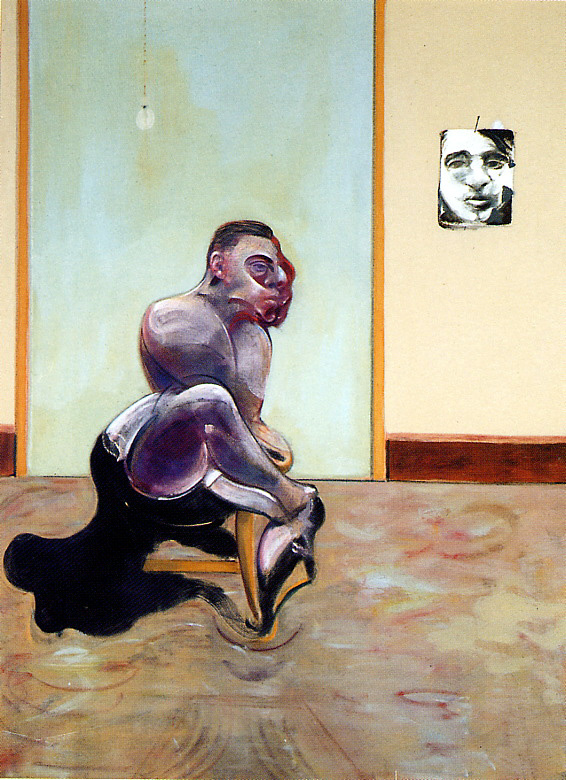

Portrait Of George Dyer

1966, 38×28 cm

Bacon met his lover George Dyer when the latter was robbing his house. At least, that’s how Bacon himself described their first meeting. It’s quite easy to imagine the confusion of Dyer, who gained entry to the artist’s apartment in South Kensington: piles of rubbish, photographs, magazines, newspaper clippings, the walls and doors covered with thick layers of paint (Bacon used them instead of the palette) and paintings everywhere (those that scared even Margaret Thatcher). Dyer was a petty crook from the East End who was far from being the brightest bulb in the chandelier. If Bacon hadn’t caught him red-handed, he would certainly have left this typical murderer’s hideout empty-handed. He simply could not imagine that the plainest sketch

would cost much more than silverware or a stereo system. Relations between Bacon and Dyer lasted eight years.

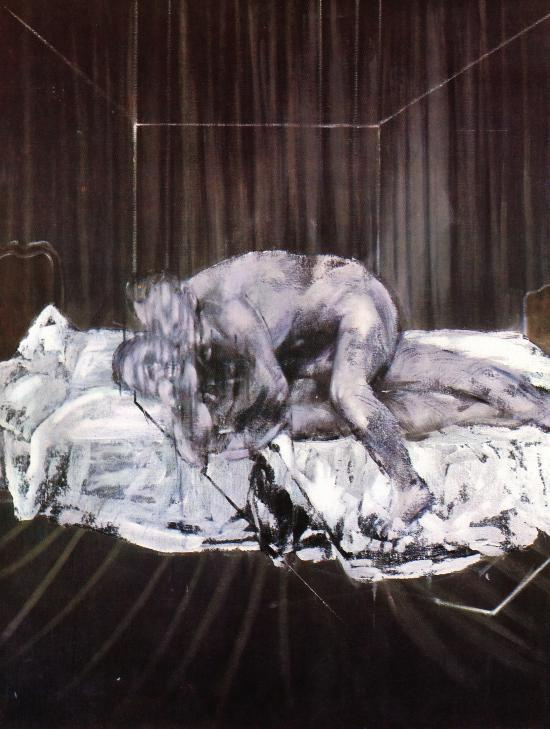

Two figures

1953, 152.7×117 cm

Once the lover threw Bacon out of the window. Bacon met Peter Lacy in the "Colony Room" in 1952. He was a retired military pilot — handsome, powerful, with a dangerously tilted psyche. Lacy worked part-time as a hired pianist at a nearby bar, and relaxed at "Colony" - according to witnesses, he could easily drink three bottles of whiskey during the evening. From the very beginning, their relationship was a nightmare: Lacy hated Bacon’s paintings and often shredded them in fits of unrestrained drunken anger. In the bedroom, he kept a collection of whips. When Bacon told his friends that Lacy "wanted to chain him up," it was not a metaphor.

During another stormy argument, Lacy threw Bacon out of the window (both of them were dead drunk). Having seen Bacon — beaten, covered with cuts and abrasions, with a nearly falling out eye — his friend Lucien Freud wanted to beat Lacy up. But the latter didn’t feel like doing that. "He would never have hit me because he was a 'gentleman,'" said Freud later — "he would never get into a fight. The violence between them was a sexual thing. I didn’t really understand all this." The more Lacy raged, the more Bacon became attached to him. In the '56, Lacy moved to Morocco, followed by Bacon. He was often seen beaten on the streets of Tangier. It came to a point where the British consul decided to intervene and asked the head of the local police for help. Finding out what’s what, the policeman reported: "I'm sorry, monsieur consul, but we are powerless here. Monsieur Bacon likes this."

During another stormy argument, Lacy threw Bacon out of the window (both of them were dead drunk). Having seen Bacon — beaten, covered with cuts and abrasions, with a nearly falling out eye — his friend Lucien Freud wanted to beat Lacy up. But the latter didn’t feel like doing that. "He would never have hit me because he was a 'gentleman,'" said Freud later — "he would never get into a fight. The violence between them was a sexual thing. I didn’t really understand all this." The more Lacy raged, the more Bacon became attached to him. In the '56, Lacy moved to Morocco, followed by Bacon. He was often seen beaten on the streets of Tangier. It came to a point where the British consul decided to intervene and asked the head of the local police for help. Finding out what’s what, the policeman reported: "I'm sorry, monsieur consul, but we are powerless here. Monsieur Bacon likes this."

Francis Bacon (photo by Douglas Glass)

Francis Bacon destroyed a lot of his paintings. When in 1936 his work was rejected by the curators of the International Surrealist Exhibition (they didn’t find it "surreal enough"), the disappointed Bacon destroyed everything he had managed to paint by that time. The next clean-up occurred in '44: the artist considered the triptych 'Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion' his first mature work and tried to collect and bury everything he had created before it. He repeatedly destroyed his own paintings, already being world famous. One day he saw his painting in the window of a gallery on Bond Street, bought it for 50 thousand pounds and immediately tore it to shreds — he was a demanding and self-critical creator.

Photos from Francis Bacon’s studio (photo: Perry Ogden, 1998).

Francis Bacon loved photos. They were his visual help (curiously enough, he did not like creating portraits in the presence of a model) and an inexhaustible source of inspiration. His whole house was filled up with photographs — scratched, quaintly crumpled and strange. He used everything — the albums of Eadweard Muybridge, the father of the motion picture, magazines, newspapers and gay porn. When he needed something specific, he asked his friend John Deakin to take a photo of it.

Deakin — a failed artist and a talented photographer — as they say, had a record. Art critic and jazz singer George Melly spoke of him like this: "vicious little drunk of such inventive malice and implacable bitchiness that it’s surprising he didn’t choke on his own venom". Of course, Bacon got on well with Deakin. Sometimes, photographing another model for Bacon, Deakin asked her to spread her legs. "Otherwise, how would Francis know?" - he explained.

Deakin — a failed artist and a talented photographer — as they say, had a record. Art critic and jazz singer George Melly spoke of him like this: "vicious little drunk of such inventive malice and implacable bitchiness that it’s surprising he didn’t choke on his own venom". Of course, Bacon got on well with Deakin. Sometimes, photographing another model for Bacon, Deakin asked her to spread her legs. "Otherwise, how would Francis know?" - he explained.

WANTED poster

. Lucian Freud, 2001.

The portrait of Francis Bacon, created by Lucian Freud, was stolen. In 1987, a retrospective exhibition of Freud went on a world tour. After the grandiose success in the United States, there were sell-outs in Paris, London and, finally, in Berlin, Freud’s homeland. The pearl of the exhibition was a small portrait of Bacon painted on a copper plate; the work in which Freud, according to a venerable critic Robert Hughes, managed to paint "that pallid pear of a face like a hand-grenade on the point of detonation".

About a month after the opening of the Berlin exposition, one of the visitors noticed a suspiciously empty place on the wall, where there was clearly supposed to hang a picture. Apparently, the thief simply unscrewed the portrait with a screwdriver and put it in his pocket.

The painting had never been found. In 13 years, when the time limit of the crime expired, Freud painted a poster (it was stuck all over Berlin and published in newspapers) asking to return the portrait for a reward of 15 thousand dollars, but everything was in vain. Robert Hughes tried to console Freud — the thief must have fallen in love with his work, since he went as far as risking so much. But he shook his head in doubt: "Oh, d’you think so? He must have been crazy about Francis."

About a month after the opening of the Berlin exposition, one of the visitors noticed a suspiciously empty place on the wall, where there was clearly supposed to hang a picture. Apparently, the thief simply unscrewed the portrait with a screwdriver and put it in his pocket.

The painting had never been found. In 13 years, when the time limit of the crime expired, Freud painted a poster (it was stuck all over Berlin and published in newspapers) asking to return the portrait for a reward of 15 thousand dollars, but everything was in vain. Robert Hughes tried to console Freud — the thief must have fallen in love with his work, since he went as far as risking so much. But he shook his head in doubt: "Oh, d’you think so? He must have been crazy about Francis."

Francis Bacon was a big fan of Sergei Eisenstein. In 1927, in Berlin, he watched "Battleship Potemkin". The film (especially the scene with a baby carriage and a nanny on the Potemkin Stairs) made an indelible impression on him. Perhaps, it was Eisenstein who was responsible for the fact that Bacon’s characters so often and loudly scream.

An important part in Bacon’s work was also taken by nipples, located in the most unexpected places — for example, on the shoulders. According to popular opinion, thus Bacon emphasized the "hermaphrodism" of his characters. Although it is possible that he took it from Eisenstein: in "Battleship Potemkin" the nipples are also weird.

An important part in Bacon’s work was also taken by nipples, located in the most unexpected places — for example, on the shoulders. According to popular opinion, thus Bacon emphasized the "hermaphrodism" of his characters. Although it is possible that he took it from Eisenstein: in "Battleship Potemkin" the nipples are also weird.

Shot from the film "Battleship Potemkin" (directed by Sergei Eisenstein, 1925).

Author: Andrii Zymohliadov

Cover illustration: Francis Bacon. Study for a Self-Portrait — Triptych