How a broken tooth opened for Michelangelo Lorenzo the Magnificent’s house; why the sculptor refused to make his David's nose even a millimetre smaller, and who disfigured his own profile; how a drawing of a kid’s hand nailed Michelangelo as a faker; why the master claimed to have sucked his love for stone in with breast milk; why he considered a flap of flayed skin to be his only true-to-life portrait — to find it all out, ArtHive had to dig into the anatomic particulars of the genius’s biography.

A child’s hand

From Bologna back to Florence, Michelangelo came penniless. Not that he needed much — in fact, he lived a remarkably ascetic life. But, after a time, even his father, Ludovico Buonarroti, started dropping the hints: it’s high time for you, a twenty-something-year-old, to make a proper living if you’ve got to reside in your father’s home again.Ludovico Buonarroti’s complaints were not without reason. So much expected, so much hoped for! Indeed, his boy, when adolescent, used to be in favour with the omnipotent gran maestro of Florence Lorenzo de' Medici, sharing his house like Lorenzo’s son. What brilliant prospects there used to open! But Lorenzo died, and his successor, the worthless Piero, was exiled from the city by the Florentines. Michelangelo, for fear of reprisals, fled to Venice, and then to Bologna. There, he was immediately taken under patronage by another nobleman — Gianfrancesco Aldovrandi, the most important person in the city. The latter, though, did not feel like showering the young sculptor with commissions. Instead, he invented a party amusement. Guests having gathered, he would open a tome of The Divine Comedy, start declaiming Dante’s terza rima — then cut it short and cast a meaningful glance at the young Florentine. Michelangelo was well aware what the audience expected from him. He would take up the line from where the host had dropped it, and go on reciting Dante from memory. He hardly ever failed, for he knew the great poem (great in length as well as in prominence) by heart. At last, he was tired of playing a local curiosity, ‘a talking head,' and returned to Florence. To his father’s place, as he had no other home.

There were some occasional commissions — all minor ones. The money they brought was not even enough to buy low-grade marble. And that stupid doll of a man, Piero Medici, with not a scrap of his father Lorenzo’s dignity, glamour, and love for art, — on his return to Florence, he, again, drove Michelangelo wild. He summoned the sculptor, who longed for real work, to his residence and commissioned a figure of Heracles made of — snow! Swearing like hell, Michelangelo made the snow effigy look like Piero — to feel malicious joy when it melt down the next day.

And suddenly, there was a commissioner! From Rome! Some Baglioni, Cardinal Raffaelle Riario di San Giorgio’s agent, visited Ludovico Buonarroti to meet his son.

Michelangelo tingled with impatience. But the visitor made no haste to speak of a commission. He inspected the arms an torsos of marble in Michelangelo’s studio, then asked him, right out of the blue, ‘Can you draw a child’s hand?'

Michelangelo tingled with impatience. But the visitor made no haste to speak of a commission. He inspected the arms an torsos of marble in Michelangelo’s studio, then asked him, right out of the blue, ‘Can you draw a child’s hand?'

Of course, Michelangelo was taken aback, but not too much. Well, after his having modelled snow Heracles, the visitor’s request was not something extraordinary. On the reverse of some sketch

, he drew a child’s chubby hand — a well-rounded, almost palpable one, as only he could do.

Male torso with clenched hands and the outline of hands

1512, 272×192 cm

Hardly had the visitor seen the picture that he rejoiced and got excited. ‘As I suspected! As I told His Eminence: your pseudo-antique Cupid is actually a present-day production; I guess it’s by that Florentine prodigy, some Michelangelo Buonarroti. A short time ago, everyone was amazed at his relief Madonna on the Stairs.'

Michelangelo flushed with displeasure. The visitor was right: the statue of Cupid the cardinal had acquired as a Roman antiquity was actually a fake, a well-worked one. None other than Michelangelo had done his best so that the statue passed as an ancient one.

Michelangelo’s being lured into the shameful forgery was not the work of the devil — or rather, the devil took the imposing form of the Roman art dealer Baldassare del Milanese. Some time before, the man had visited the young jobless sculptor to make an offer. The Eternal City, said the tempter, was smitten with a sheer epidemic. The native nobility, the church hierarchy — all were obsessed with antiquities. Rome was almost turned inside out, excavations never stopped even for the night, every day something rare and valuable was extracted from under the ground. The prices for antiquities had shot up. So, could signor Buonarroti make something, like a relief or a sculpture, that would have imitated ancient artworks? Of course he could — there was no doubt about it after he created his Battle of the Centaurs. And what if make the piece seem ancient? The old age would certainly be paid much more than a beginner’s work.

Michelangelo flushed with displeasure. The visitor was right: the statue of Cupid the cardinal had acquired as a Roman antiquity was actually a fake, a well-worked one. None other than Michelangelo had done his best so that the statue passed as an ancient one.

Michelangelo’s being lured into the shameful forgery was not the work of the devil — or rather, the devil took the imposing form of the Roman art dealer Baldassare del Milanese. Some time before, the man had visited the young jobless sculptor to make an offer. The Eternal City, said the tempter, was smitten with a sheer epidemic. The native nobility, the church hierarchy — all were obsessed with antiquities. Rome was almost turned inside out, excavations never stopped even for the night, every day something rare and valuable was extracted from under the ground. The prices for antiquities had shot up. So, could signor Buonarroti make something, like a relief or a sculpture, that would have imitated ancient artworks? Of course he could — there was no doubt about it after he created his Battle of the Centaurs. And what if make the piece seem ancient? The old age would certainly be paid much more than a beginner’s work.

And Michelangelo accepted the proposition — or rather rose to the challenge. Not out of the lack of money — if only for this, he would never have bothered. But he felt the thrill of the competition: surely, he would manage just as well as the ancient. He would outwit those art-loving snobs and make fools of them. It was not a problem for him to make a sculpture look older. So often, when learning in Ghirlandajo’s bottega, he would masterfully do it with his drawings using sand, smoke, and ashes.

Following del Milanese’s advice, Michelangelo carved Cupid out of marble. Having done that, the sculptor became a chemist. This is how Alexander Makhov describes the unappetising details of the fabrication process: the sculptor coated Cupid with a mixture of faeces, mould, and soured milk. When the figure dried in the sun, he buried it in the garden. Three weeks later, the statue extracted from the pit could hardly be recognised: the marble darkened, as if tarnished by centuries.

Now the young master stood uncovered in front of the Cardinal’s agent, who told him that Pope himself never approved of that sort of practice.

‘Have I brought condemnation upon myself?'

‘Quite the contrary. Cardinal di San Giorgio is inviting you to Rome. He promises you work and residence in his palace.'

Now the young master stood uncovered in front of the Cardinal’s agent, who told him that Pope himself never approved of that sort of practice.

‘Have I brought condemnation upon myself?'

‘Quite the contrary. Cardinal di San Giorgio is inviting you to Rome. He promises you work and residence in his palace.'

Madonna of the stairs

1490, 55×40 cm

The breasts of a stonemason’s wife

Michelangelo never took such satisfaction in paints as he did in marble. He preferred the chisel to the paintbrush. He had always done. Even when working on the great Sistine Chapel frescos, he kept signing his letters Michelagniolo scultore in Roma (Michelangelo the sculptor, Rome).He joked that he had sucked in his passion for stone while breastfed.

His mother, fragile Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, aged nineteen, did not even try to put her new-born child to her breast. Even if she did not share the aristocratic prejudice against breastfeeding as something plebeian, she, nevertheless, was too weak for it after the difficult labour and delivery. Despite her young age, Michelangelo (named after Archangel Michael) was her second child. The pregnancy was difficult. In the middle of it, Francesca fell down from a horse. None of the doctors invited by her husband dared to predict its outcome. The father, Ludovico Buonarroti, the mayor of the town of Caprese, found it beyond belief that the boy was born healthy. When the nurse tried to pop a feeding horn with goat milk into his mouth, the child would spit with disgust and cry, thus manifesting his natural obstinacy that was to become legendary when Michelangelo got fame.

Zenobia

1525

The family decided to take one-and-a-half-month-old Michelangelo to their old estate of Settignano, near Florence, famous for its marble quarries. Michelangelo’s grandmother, who lived there, succeeded in getting the baby in care of her young neighbour, ample-breasted, corpulent, and kind Margarita, who had just had her third child. She was married to Domenico di Giovanni di Bertini Fancelli, a local stonemason, called for his shortness and frailty Topolino (‘Little Mouse'). Their three sons, including Michelangelo’s foster brother Enriche, would become stonemasons, too.

For Michelangelo, it was the finger of fate. Spending his childhood in Settignano among the masses of marble, rock dust, and monotonous hammering, he grew fond of stone. Very early he developed an eye for its texture, coarseness, the quality of polishing, hardness. He could even eyeball its weight.

When Michelangelo was five or six, his mother passed away, exhausted with pregnancies, having delivered Ludovico’s fifth son. Stacks of psychoanalytical investigations have been written, where Michelangelo’s disagreeable temper and unsociable demeanour have been explained by the lack of mother’s love and tenderness. And when he occasionally visited Settignano, he jokingly called Mona Margarita mother.

Madonna on the Stairs, Michelangelo’s first relief that immediately made the beginner sculptor famous, is something more than just adoration of the Blessed Virgin. It is an act of homage to the woman who milk-fed him. The three mischievous putti on the stairs are an allusion to Margarita’s sons, whose company Michelangelo grew up in.

Michelangelo chose a popular iconographic subject, Madonna del Latte (Nursing Madonna). But being a better expert in nudity than anyone, he, though, did not present his Madonna open-breasted. The breast of the artist’s model could have been made an object of admiration and aesthetic delight. But Michelangelo had in mind another breast, the one that had nursed him. That is why he modestly hid it behind the baby’s head.

Madonna on the Stairs, Michelangelo’s first relief that immediately made the beginner sculptor famous, is something more than just adoration of the Blessed Virgin. It is an act of homage to the woman who milk-fed him. The three mischievous putti on the stairs are an allusion to Margarita’s sons, whose company Michelangelo grew up in.

Michelangelo chose a popular iconographic subject, Madonna del Latte (Nursing Madonna). But being a better expert in nudity than anyone, he, though, did not present his Madonna open-breasted. The breast of the artist’s model could have been made an object of admiration and aesthetic delight. But Michelangelo had in mind another breast, the one that had nursed him. That is why he modestly hid it behind the baby’s head.

The toothless excellence

Aged thirteen, Michelangelo started his apprenticeship at the Ghirlandajo brothers' bottega. His notoriously miserly father arranged things to his advantage and had the brothers pay him for training the talented boy in their studio. The agreement was for a term of three years, but Michelangelo only completed one. Early did he realise that sculpture was dearer to him than painting, so he transferred to the sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni, whom the Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici had chosen to organise an academy for sculptors.Bertoldo’s academy was located in Medici’s garden. Not the trees were planted there, but statues — a priceless collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, amassed by several Medici generations. Michelangelo could amble among them for hours. One day, he saw an ancient mask of a faun — and felt that he was ready.

Vasari relates how Michelangelo, ‘encouraged, after some days set himself to counterfeit from a piece of marble an antique head of a Faun that was there, old and wrinkled, which had the nose injured and the mouth laughing.'

Michelangelo working on the faun’s head.

At that time, Michelangelo was only fourteen, fifteen at the most. He may be said to have never yet touched chisels or marble. It was the first sculpture he had made in his life, and he succeeded miraculously. Not only did the young man imitate the ancient model, but he unleashed his imagination and improved the work. He opened the faun’s mouth in a beastly grin, with all the teeth bared and tongue exposed. The teeth were really superb, pearly ones.

Lorenzo Medici, the uncrowned king of Florence, found Michelangelo doing it. As Marcel Brion puts it in Michelangelo’s biography, every Florentine knew that man ‘with the long face, the ugly nose, the prominent jaw, and the blotched complexion, the unpleasantness of which was completely lost in the radiance of his intelligence. Michelangelo had often seen him from a distance, for he frequently visited the monastery of San Marco and strolled in the cloister with learned monks and the philosophers of his court, but he had never been close to him and he had never heard his voice. And now he was speaking to him and gazing with his dark eyes at the head of a faun in the boy’s hands.'

Lorenzo was greatly impressed with Michelangelo’s faun. Could anyone have expected from a fourteen-year-old youth a piece so excellent! However, undisguised admiration was not Lorenzo’s way. In his usual bantering style, he said to Michelangelo, ‘Surely you should have known that old folks never have all their teeth, and that some are always wanting.'

No sooner had the footsteps of Magnificent Lorenzo, leaving, faded away than Michelangelo broke out one of the faun’s teeth, and then filed the gap smooth so artfully that the tooth seemed to have just dropped out of the gum.

Most of Michelangelo’s biographers agree that it was after this episode that Lorenzo the Magnificent started patronising Michelangelo. According to Vasari, ‘he sent for his father Lodovico and asked for the boy from him, saying that he wished to maintain him as one of his own children; and Lodovico gave him up willingly. Thereupon the Magnificent Lorenzo granted him a chamber in his own house and had him attended, and he ate always at his table with his own children and with other persons of quality and of noble blood who lived with that lord, by whom he was much honoured.' Michelangelo’s father, however, again did pretty well himself, for ‘During that time, then, Michelagnolo had five ducats a month from that lord as an allowance and also to help his father; and for his particular gratification Lorenzo gave him a violet cloak, and to his father an office in the Customs.'

Lorenzo Medici, the uncrowned king of Florence, found Michelangelo doing it. As Marcel Brion puts it in Michelangelo’s biography, every Florentine knew that man ‘with the long face, the ugly nose, the prominent jaw, and the blotched complexion, the unpleasantness of which was completely lost in the radiance of his intelligence. Michelangelo had often seen him from a distance, for he frequently visited the monastery of San Marco and strolled in the cloister with learned monks and the philosophers of his court, but he had never been close to him and he had never heard his voice. And now he was speaking to him and gazing with his dark eyes at the head of a faun in the boy’s hands.'

Lorenzo was greatly impressed with Michelangelo’s faun. Could anyone have expected from a fourteen-year-old youth a piece so excellent! However, undisguised admiration was not Lorenzo’s way. In his usual bantering style, he said to Michelangelo, ‘Surely you should have known that old folks never have all their teeth, and that some are always wanting.'

No sooner had the footsteps of Magnificent Lorenzo, leaving, faded away than Michelangelo broke out one of the faun’s teeth, and then filed the gap smooth so artfully that the tooth seemed to have just dropped out of the gum.

Most of Michelangelo’s biographers agree that it was after this episode that Lorenzo the Magnificent started patronising Michelangelo. According to Vasari, ‘he sent for his father Lodovico and asked for the boy from him, saying that he wished to maintain him as one of his own children; and Lodovico gave him up willingly. Thereupon the Magnificent Lorenzo granted him a chamber in his own house and had him attended, and he ate always at his table with his own children and with other persons of quality and of noble blood who lived with that lord, by whom he was much honoured.' Michelangelo’s father, however, again did pretty well himself, for ‘During that time, then, Michelagnolo had five ducats a month from that lord as an allowance and also to help his father; and for his particular gratification Lorenzo gave him a violet cloak, and to his father an office in the Customs.'

David. Fragment

1504

David’s nose and Michelangelo’s nose

In 1461, the sculptor Agostino di Duccio failed the commission from the Office of Works of Florence Cathedral. A huge marble block he had roughly chiselled remained neglected in a Florentine churchyard. Forty years later, in 1501, it was decided to have it turned into a finished work of art. The Office began looking for an artist to carve a statue of David. It was supposed to symbolise the valour of the citizens of Florence who had defended their city against the King of France’s army.Many were offered the task, among them another native of the Florentine region, Leonardo da Vinci. No-one agreed: the marble was too problematic. No-one — but Michelangelo. Quite likely, it was just to spite Leonardo, his eternal rival.

The job took three years. Since then, for half a millennium, Michelangelo’s David has remained one of the mankind’s main landmarks in the realm of Beauty. The four-metre-tall statue is beautiful in every single detail: from the calf muscles to the strong jaw, from the tense neck to the hands. David’s glance expresses and imbues the viewers with the emotion that is termed as la terribilità. As Alexei Dzhivelegov, an expert in classical antiquity, explains, ‘it is not quite the quality of provoking terror (the literal meaning), but an impact of a statue or a picture that can shake the viewer’s composure, make him experience his impression in a state of intense inner agitation.'

There were, though, some of Michelangelo’s contemporaries who understood beauty in an alternative way. One of these, the gonfaloniere Piero Soderini, once disliked David’s nose!

Vasari writes, ‘It happened at this time that Piero Soderini, having seen it in place, was well pleased with it, but said to Michelagnolo, at a moment when he was retouching it in certain parts, that it seemed to him that the nose of the figure was too thick. Michelagnolo noticed that the Gonfalonier was beneath the Giant, and that his point of view prevented him from seeing it properly; but in order to satisfy him he climbed upon the staging, which was against the shoulders, and quickly took up a chisel in his left hand, with a little of the marble-dust that lay upon the planks of the staging, and then, beginning to strike lightly with the chisel, let fall the dust little by little, nor changed the nose a whit from what it was before. Then, looking down at the Gonfalonier, who stood watching him, he said, "Look at it now." "I like it better," said the Gonfalonier, "you have given it life."'

Thus, the sculptor, instead of making a small nose, made a long one — at the gonfaloniere. For Michelangelo, a perfectly straight, Greek nose was the principle of the thing. His own profie had been disfigured, as early as in his green youth, by the sculptor Pietro Torrigiano.

The memoirs by another sculptor, Benvenuto Cellini, contain Torrigiano’s account of his assault on Michelangelo. ‘This Buonarroti and I used, when we were boys, to go into the Church of the Carmine, to learn drawing from the chapel of Masaccio. It was Buonarroti’s habit to banter all who were drawing there; and one day, among others, when he was annoying me, I got more angry than usual, and clenching my fist, gave him such a blow on the nose, that I felt bone and cartilage go down like biscuit beneath my knuckles; and this mark of mine he will carry with him to the grave.'

Michelangelo (as sensitive to ugliness as he was to beauty) is told to have considered his deformed face a shame. And Torrigiano, though not quite untalented a sculptor, has remained forever in history as ‘the guy who broke Michelangelo’s nose.'

Thus, the sculptor, instead of making a small nose, made a long one — at the gonfaloniere. For Michelangelo, a perfectly straight, Greek nose was the principle of the thing. His own profie had been disfigured, as early as in his green youth, by the sculptor Pietro Torrigiano.

The memoirs by another sculptor, Benvenuto Cellini, contain Torrigiano’s account of his assault on Michelangelo. ‘This Buonarroti and I used, when we were boys, to go into the Church of the Carmine, to learn drawing from the chapel of Masaccio. It was Buonarroti’s habit to banter all who were drawing there; and one day, among others, when he was annoying me, I got more angry than usual, and clenching my fist, gave him such a blow on the nose, that I felt bone and cartilage go down like biscuit beneath my knuckles; and this mark of mine he will carry with him to the grave.'

Michelangelo (as sensitive to ugliness as he was to beauty) is told to have considered his deformed face a shame. And Torrigiano, though not quite untalented a sculptor, has remained forever in history as ‘the guy who broke Michelangelo’s nose.'

Tomb of Pope Julius II. Moses (fragment)

1515, 235 cm

The prophet’s knee

'What shall I tell you about celebrated Rome?' wrote Ilya Repin. 'I don’t like it at all. Rome is a dead city that has seen its day. … Only Michaelangelo strikes with force. As for the rest, including Raphael, it is old and so childish that one loses the desire to see it. … However, Michaelangelo’s Moses is worth everything else.'And Sigmund Freud’s remark seems to echo Repin’s. ‘It always delights me to read an appreciative sentence about this statue, such as that it is "the crown of modern sculpture." For no piece of statuary has ever made a stronger impression on me than this.'

Moses is not a stand-alone sculpture, but the pivotal figure of a grand architectural and memorial complex, Pope Julius II’s tomb. That very tomb that brought upon Michelangelo misfortunes, shame, trials…

Rome, during its history, has witnessed different popes: money-grubbing and licentious ones, conservative and reformist, divinely inspired and totally inappropriate for the position. Julius II was the most pugnacious pope. His pontificate is remembered as a series of wars. Rome opposed Venice, then France, increased in new territories, and the pope would even himself lead the cavalry, with the holy sacrament carried ahead. Not only did he evince his fighting spirit in politics, but in everyday life as well. He used to club the bolshie sculptor with his stick and threaten to push him off the scaffolding. Michelangelo would flee, only to return back after a while: of all the thirteen popes who were his contemporaries, Julius had the best appreciation of art. Though he never ceased to hurry him up and pester him with criticism, still he did love Michelangelo sincerely.

Pope Julius had an idea of a magnificent edifice — his own tomb. A giant sarcophagus, decorated with forty figures above human size. He admired Michelangelo’s design, the sculptor was given money so that he himself could select the best marble and transport it from Carrara. However, the enterprise of great pitch and moment came to a standstill soon. Another idea struck the pope — frescoing the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo, though he did his best to avoid it, had to take on the role of a painter. The tomb was to be put aside. Then Julius died, a few other popes followed one by one, Julius’s heirs sued Michelangelo for outstanding commitments and defalcation — and won the case. The tomb was redesigned again and again, the contracts reconcluded, and all that soul-sucking drag lasted forty years. Michelangelo’s biographers have no other term for it, but the ‘tragedy of the sepulchre.'

But his contemporaries well realised that the statue of Moses alone was enough to immortalise Pope Julius, whom Michelangelo made his Moses to resemble — both in face and spiritually.

Pope Julius had an idea of a magnificent edifice — his own tomb. A giant sarcophagus, decorated with forty figures above human size. He admired Michelangelo’s design, the sculptor was given money so that he himself could select the best marble and transport it from Carrara. However, the enterprise of great pitch and moment came to a standstill soon. Another idea struck the pope — frescoing the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo, though he did his best to avoid it, had to take on the role of a painter. The tomb was to be put aside. Then Julius died, a few other popes followed one by one, Julius’s heirs sued Michelangelo for outstanding commitments and defalcation — and won the case. The tomb was redesigned again and again, the contracts reconcluded, and all that soul-sucking drag lasted forty years. Michelangelo’s biographers have no other term for it, but the ‘tragedy of the sepulchre.'

But his contemporaries well realised that the statue of Moses alone was enough to immortalise Pope Julius, whom Michelangelo made his Moses to resemble — both in face and spiritually.

Portrait of Pope Julius II

1512, 108.7×81 cm

Michelangelo was always very critical of himself. Always did it seem to him that his marbles were much inferior to the divine design. That is why he left unfinished so many of his works. He abandoned them, either hoping to complete them some day later, or having given up in his struggle with the material that refused to take the shape he wanted.

But this time, even he, who had always been hypercritical of his own works, was satisfied. He was contemplating Moses, squinting and panting with excitement. Suddenly, he cried out, ‘You live! Why won’t you go?'

The figure made no move, and Michelangelo, with all his strength, slashed the prophet’s marble knee with the chisel. The small scar on the stone still reminds us of the genius’s ecstasy and despair.

But this time, even he, who had always been hypercritical of his own works, was satisfied. He was contemplating Moses, squinting and panting with excitement. Suddenly, he cried out, ‘You live! Why won’t you go?'

The figure made no move, and Michelangelo, with all his strength, slashed the prophet’s marble knee with the chisel. The small scar on the stone still reminds us of the genius’s ecstasy and despair.

‘Paunch and buttock’

When we view the ceiling in the Sistine Chapel and admire the ingenious angles and perspectives of the bodies that, though painted, never seem still, but stay in endless motion, — do we ever remember another body, the one that brought all this heavenly harmony to life centuries ago? We are used to thinking of the Sistine Chapel in connection with Adam’s and God the Father’s hands that try to reach each other and never succeed, with the sibyls' mighty triceps, with the saints' emphatic legs and torsos. For Michelangelo, for his somatic memory, the Chapel was associated with quite different body parts:I’ve grown a goitre by dwelling in this den —

As cats from stagnant streams in Lombardy,

Or in what other land they hap to be —

Which drives the belly close beneath the chin:

My beard turns up to heaven; my nape falls in,

Fixed on my spine: my breast-bone visibly

Grows like a harp: a rich embroidery

Bedews my face from brush-drops thick and thin.

My loins into my paunch like levers grind:

My buttock like a crupper bears my weight;

My feet unguided wander to and fro;

In front my skin grows loose and long; behind,

By bending it becomes more taut and strait;

Crosswise I strain me like a Syrian bow:

Whence false and quaint, I know,

Must be the fruit of squinting brain and eye;

For ill can aim the gun that bends awry.

These lines by Michelangelo tell us about his physical torment during his work at the Chapel’s ceiling.

‘Just imagine, for an instant, the scaffolding raised high up to the ceiling,' writes Igor Dolgopolov, a journalist and poster designer. ‘The door of the Sistine Chapel locked. Silence. Solitude. And there, on the staging, beneath the very plafond, — him: supine, faint with pain, exhausted, stubbly-faced, having no quiet sleep, nor rest, nor even a chance to take off his boots once in weeks, worn out, ceaselessly criticised by the papal court, spurred on by his fastidious patron, the pope himself… Him — Michelangelo, a human made of flesh and bones, performing his superhuman feat inch by inch. Day after day, month after month, year after year!'

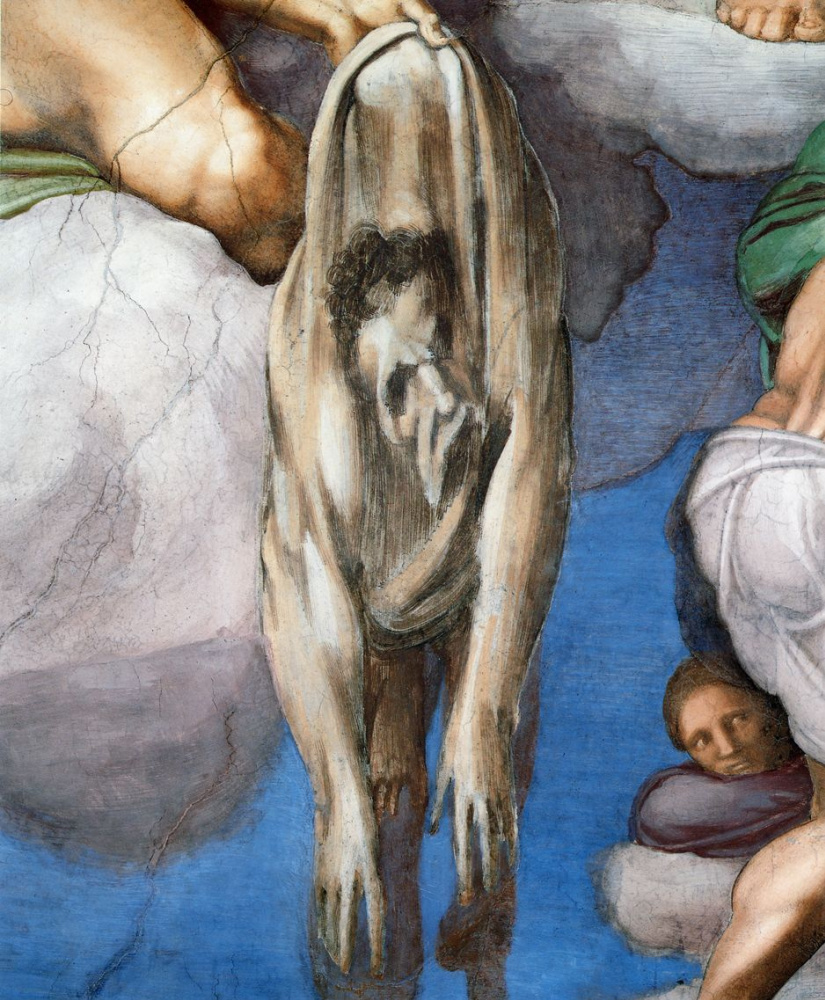

More than two decades after painting the frescos on the ceiling, Michelangelo was invited to decorate the altar wall in the same Chapel with a picture of the Last Judgement. There, the artist’s only self-portrait is to be found. Generally, Michelangelo never portrayed himself. Some think that, unlike Raphael, a real beauty, he detested his own looks, others believe he viewed self-portraying as an act of unreasonable vanity. Both explanations look like true. But in his mature age, he found a form of self-portrait, which must have seemed to him adequate. Michelangelo’s self-portrait on the wall of the Sistine Chapel is a piece of skin flayed off St. Bartholomew!

Text by: Anna Vcherashnyaya