This is the story of a real, long, passionate love affair, which took place at the end of the 19th century not in Paris, but in the mind and hearts of two brilliant artists. Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot could not be together, since they were bound by obligations, moral principles and personal beliefs. And in the end, they created their own artistic dimension, in which they found freedom and the opportunity to spent hours, declaring their love and softly whispering in each other’s ears. It was their own parallel pictural universe.

The mystery of the Trocadéro Hill

Édouard Manet’s biography contains so many mysteries and understatements that the confusing story of the Trocadéro Hill is not the fruitiest or most striking one. But it is this story that one should begin with when it comes to Berthe Morisot.Thanks to Manet’s biographer Henri Perruchot, the mystical and romantic legend keeps appearing online and on the pages of beauty magazines and even serious publications, stating that Manet saw View of Paris from the Trocadéro even before meeting Berthe. Manet was so impressed with the painting that he created his own one — from the same place: standing on the hill and looking at the Champs de Mars. By the way, Manet often turned to the paintings of other artists, reinterpreting their ideas and compositions. But he did it with indisputable masterpieces and geniuses: Goya, Raphael, Giorgione, Titian. But that time it was a beginning artist no one heard of!

The legend is beautiful — it would very precisely illustrate the affinity of souls and talents, confirming that even before they met, these two artists had been living in the same artistic dimension and breathing the same pictural air, anticipating and expediting the watershed moment when they first met… If it hadn’t been for one unfortunate slip: Manet’s View of the 1867 Exposition Universelle was created 5 years earlier than Berthe Morisot’s View of Paris from the Trocadéro.

View of Paris from the Trocadéro

1872, 46.1×81.5 cm

Art historian Kathleen Adler sees a real drama in the pastoral (at first glance) painting by Berthe Morisot: the year before, in 1871, there was a war in Paris, when the city was under siege for a long time — it had only been a few months after the suppression of the Paris Commune. That was Paris between the past and the future; in just 17 years the Eiffel Tower would add to the landscape

. But the women behind the fence are separated from the city not only physically but also emotionally. They are in a protected world, isolated from the world of war and business, from the world of men.

World exhibition

1867, 108×196 cm

That year, the Exposition Universelle in Paris displayed not only technical but also artistic achievements of the participating countries. The disgraced artist Édouard Manet challenged the judges of the Salon and opened at the exhibition his own pavilion with 50 of his best paintings created in 10 years.

And everything turns out to be more complicated than at the first admiring glance. Perhaps, in 1872, it wasn’t the first time when Berthe Morisot came to Trocadéro with her easel, and Manet admired a completely different view of Paris painted by her earlier. And most likely, everything was the other way around — Berthe could paint the Trocadéro Hill after Manet, who having experienced the siege and war in Paris with her, went to his family. "This place reminds me of Manet. I am aware of it and I am annoyed," Berthe Morisot wrote to her sister while working on this painting. The French Wikipedia page on Berthe Morisot even states that it was the View of Paris from the Trocadéro that Édouard Manet showed to art dealer Durand-Ruel in 1872, wanting to introduce him to Berthe’s work. Durand-Ruel was amazed and sold the painting to the collector Ernest Hoschedé.

The Balcony

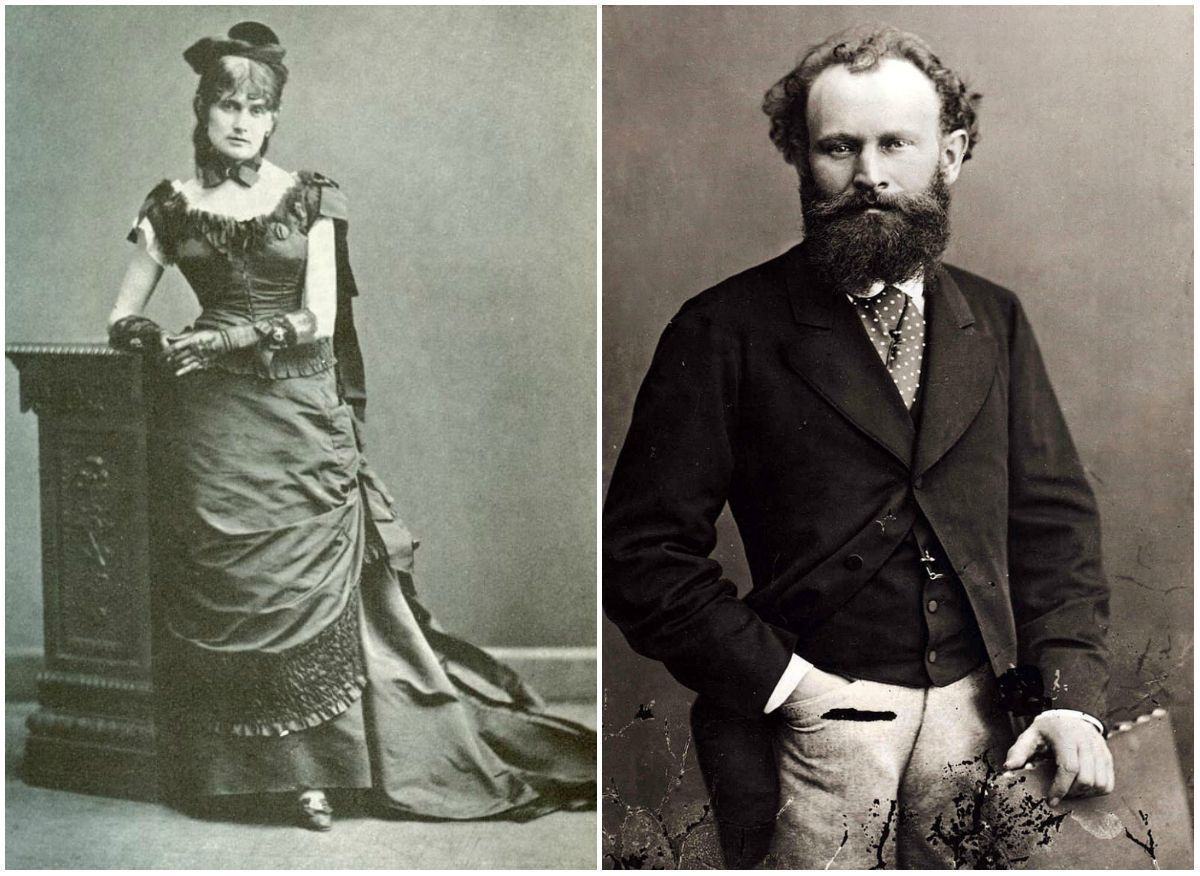

Whatever it be with premonitions and signs, the first meeting of Édouard and Berthe Morisot happened in the Louvre in 1868. The artist Henri Fantin-Latour introduced the Morisot sisters, Edma and Berthe, to the idol of all young painters, this scandalous and brilliant Manet, who became the talk of Paris after his Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia. Berthe was 27 years old and she didn’t want to settle down to married life, while her freethinking and refusing numerous admirers were seriously bothering her mother. And Manet had been married for a long time and was raising a child who was either the artist’s son or brother.

Balcony

1869, 169×123 cm

Having seen Berthe in the Louvre, Manet immediately realized who would become the model for his new painting. Just a little while ago, he planned to paint a group portrait, based on Goya’s Majas on a Balcony but couldn’t find one of the heroines. He immediately asked Berthe to pose for him.

Morisot could not refuse the best artist of their time — she could have sessions every day, come to his studio, see his unfinished sketches, and finally understand what the secret of his amazing painting was. Of course, she came there with her mother, who would sit aside, knit and occasionally look at Manet.

Once, Madame Morisot half-jokingly said, "He looks like a madman." And Manet really was not quite himself: he refused profitable commissions not to miss their meetings, which would often make him shake with excitement, he would avidly grab his brushes, if Berthe half-turned to him or tiredly sat in a chair. He couldn’t resist painting her.

When the painting Balcony appeared at the Salon of 1869, the rumours about the "fatal woman" quickly spread through the halls, and Berthe’s acquaintances dropped her hints that the artist had painted her quite ugly. "I am more strange than ugly," Morisot wrote to her sister.

Morisot could not refuse the best artist of their time — she could have sessions every day, come to his studio, see his unfinished sketches, and finally understand what the secret of his amazing painting was. Of course, she came there with her mother, who would sit aside, knit and occasionally look at Manet.

Once, Madame Morisot half-jokingly said, "He looks like a madman." And Manet really was not quite himself: he refused profitable commissions not to miss their meetings, which would often make him shake with excitement, he would avidly grab his brushes, if Berthe half-turned to him or tiredly sat in a chair. He couldn’t resist painting her.

When the painting Balcony appeared at the Salon of 1869, the rumours about the "fatal woman" quickly spread through the halls, and Berthe’s acquaintances dropped her hints that the artist had painted her quite ugly. "I am more strange than ugly," Morisot wrote to her sister.

Rest. Portrait of Berthe Morisot

1870, 150.2×114 cm

Violets

Educated and intelligent, often silent and restrained, too independent and talented, Berthe knew the value of her own style and personality. It was already difficult to exert a direct influence on her painting — and Manet simply freed her from doubts and directed the artist in her search. But he himself couldn’t do without her.

Portrait of Berthe Morisot with bouquet of violets

1872, 55×38 cm

Édouard Manet. Portrait of Eva Gonzalès, 1870

In 1970, a young pupil appeared in the artist’s studio — it was 20-year-old Eva González who gave Manet a great opportunity to annoy Berthe and prove to himself that he could easily replace Morisot with any other model and muse. But it was not to be — Eva’s portrait came to no good and even after 40 sessions, it still looked artificial, lacking life and naturalness. Manet was enraged and decided to take his revenge on no one else but Berthe. Trying his best at praising the hard-working Eva, he would even throw her to Berthe’s face.

In one of the letters to her sister, Berthe wrote: "It seems that what I do is decidedly better than Eva Gonzalès. Manet is too candid, and there can be no mistake about it. I am sure that he liked these things a great deal; however, I remember what Fantin says, namely, that Manet always approves of the painting of people whom he likes."

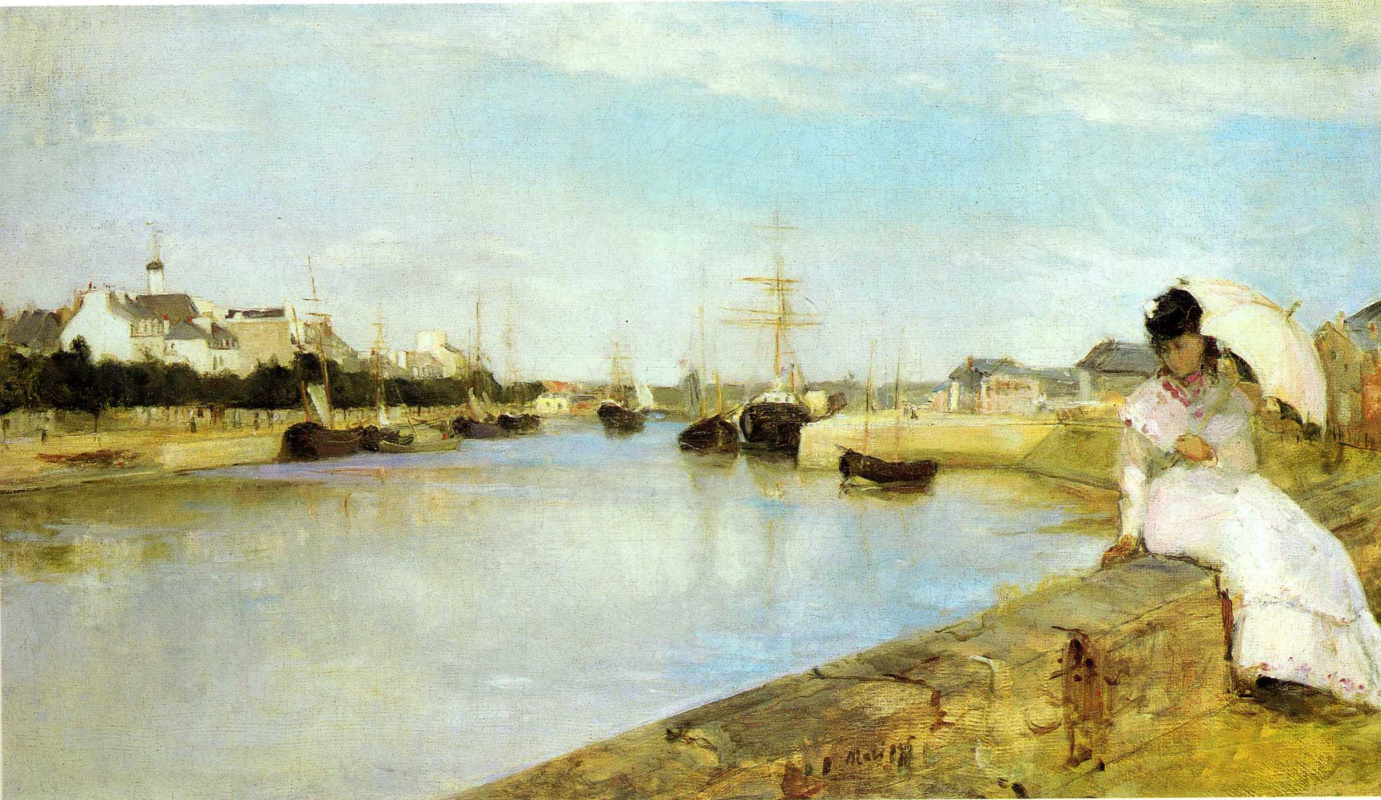

The port in Lorient

1869, 43.5×73 cm

Manet’s praise and love gave Morisot strength and confidence: once, the artist admired her ability to fit a figure into the landscape — and Berthe gave him that painting.

The fan

Berthe Morisot was the only woman in the 'Manet gang' - a term, used to describe young artists who defied traditional painting and Salon (in a few years they would be called "Impressionists"). In the evenings, she could not come together with male artists to the Café Guerbois, where her friends argued about the fate and purpose of art, but she would gladly receive them in her parents' house and join them for plein air painting, talking about the same things.In 1870, the themes for the evening conversations changed — first, the war began, and later — the grueling siege of Paris. In the evenings, Manet and Degas would often come to Morisot’s house, but they generally talked about the ways of defense and the possibilities of the National Guard, where both of them served as volunteeres. Manet’s brother Eugène also became a frequent visitor to Morisot’s house. Hunger and diseases reigned in the city, people ate cats and bought donkey meat at triple the price — neither Morisot nor Manet painted during those years.

Berthe Morisot with a fan

1872, 60×45 cm

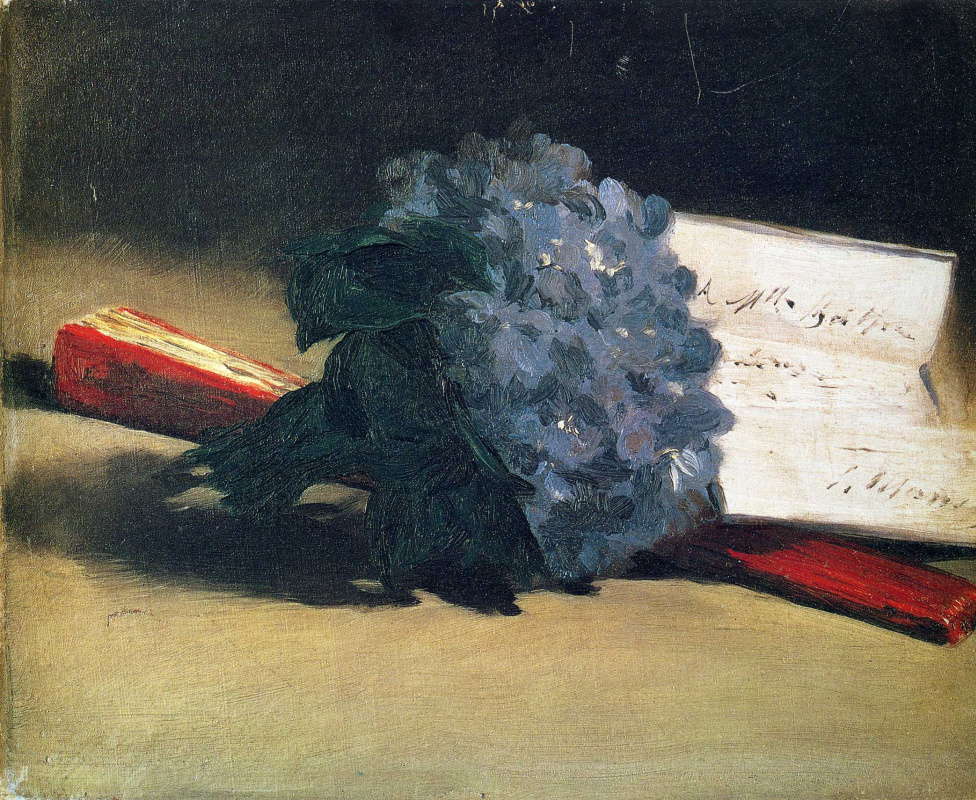

The last present

In 1873, Berthe turned 32 and understood: she had a man at her side, whom she could marry and remain faithful to her vocation. Over the past few years, Eugène Manet, Édouard 's brother, had become very close to her: it was easy and fun with him, he understood and appreciated her painting. And he was Manet, too.There were more and more talks about the wedding in Morisot and Manet’s families. And the whole romantic story of the passionate, impossible love between Édouard and Berthe could seem to be a myth, if it wasn’t for the two eloquent paintings, Bouquet of Violets and the last portrait of Berthe, painted in 1874.

Bouquet of violets

1872, 27×22 cm

Bouquet of Violets is a timid and nervous ellipsis that Manet put in this relationship, being somewhat mystified at why it ended. He sent the painting to Berthe, like the hurt lover returns gifts, reminiscent of the bygone happiness. The portrait contains violets from the first portrait of Berthe and a fan from the second one; the artist also wrote "to Mademoiselle Morisot" on the sheet of paper.

Portrait of Berthe Morisot

1874, 50.5×61 cm

Manet painted the last portrait of Berthe Morisot in the year of her wedding with Eugène, with Berthe wearing a ring on her finger, and her whole pose conveying a suspension, a sudden movement backwards, serious and persistent. That ring created the everlasting abyss between the two of them, putting an end to the long and desperate relationship. Immediately after the wedding, Berthe wrote to her sister: "I have found an honest and excellent man who, I believe, sincerely loves me. I have entered into the positive life after having lived for a long time in by chimeras."

Eugène became an excellent husband, he not only allowed Bertha to paint, but also, alongside his legal practice, became her assistant and manager: he was carrying her easel, managed the placement of her paintings at exhibitions, wrote long and detailed letters about the exhibition of the Impressionists, critics and friends at the time when Berthe could not be present there personally due to her pregnancy. Four years after the wedding, Berthe and Eugène had a daughter, Julie, who became Morisot’s best model and helped the artist discover a new meaning of her painting: making momentary eternal.

Afterword

The railway

1873, 93×114 cm

Nevertheless, Berthe Morisot got on the list of the artists who influenced Édouard Manet and whose motifs he borrowed. In 1872, Berthe painted a woman and a girl at the fence, and in 1873, Manet used that composition in one of his masterpieces. "How skillfully she fits a figure into the landscape

!"

Author: Anna Sidelnikova

Author: Anna Sidelnikova