Speaking the street language

Aristide Bruant was born in 1851, in the village of Courtenay, into a well-off landowning family. He knew no poverty, was careless and happy. But when he was only twelve, his family situation declined drastically. One theory is that it was due to his father’s death, another one ascribes it to his imprudence in dealing with money followed by the family’s financial ruin. Whatever the case, the bright pupil, who had had the top grades and awards in Latin, Greek, History, and Singing, had no other choice but leave school, head to Paris, and earn his living himself.He changed a number of residences and workshops in different working-class areas. He served apprenticeships, assisted craftsmen, and spent the rest of the time messing around with bad guys, trouble-makers, tramps, workers. In the evenings, in the course of long chats with his new friends, Aristide learned to speak their language — and was captivated by the French labour district slang. He picked up caustic quips, acerbic catchwords, cynical remarks, and enjoyed using them in his own speech. Though lacking proper education, Bruant was curious and meticulous. In his studies of the vernacular, he did not content himself with listening to pimps' drunken skirmishes, but visited libraries. There, he diligently studied dictionaries of slang and collections of verse of François Villon’s time. In the same manner as he had perfectly mastered Latin and Greek in his childhood, now he was mastering the language of his songs-to-be — the language that no-one had ever sung in before, the one that would bring him fame.

He had to drop the studies of the Parisian riff-raffs' parlance for the period of the Franco-Prussian War. Twenty-year-old Aristide served as a sniper through all of it, start to finish. On his return, he was given a lucrative job, a much-coveted one, in the Northern Railway Company. But he was only able to endure his boring responsibilities for four years. Twenty years later, Bruant would decide to run for political office, and Léon de Bercy would give a campaign lecture about him. Of course, the lecture was full of romanticism and fiction — a typical campaign speech. That is how Bercy referred to the railway office period.

‘… Bruant pour vivre, joined the Northern Railway Company. But he loves the theatre, and the sedentary life, the office life weighs him: he dreams of freedom, and in the evening, during the hours of leisure that leaves him his existence as an employee, he runs the goguettes <…>. He has the look, the trunk and the confidence in himself; his boldness and frankness serve him well: he is encouraged. It was then that he wrote his first songs, of a character still undecided but in a new, original way already; for he uses the colourful language of the street, the language of the people <…>. He is gradually getting rid of banal conventions; <…> and, after taking from the people his way of expressing himself, he will take the thought and give it back, to serve it: his way is found.'

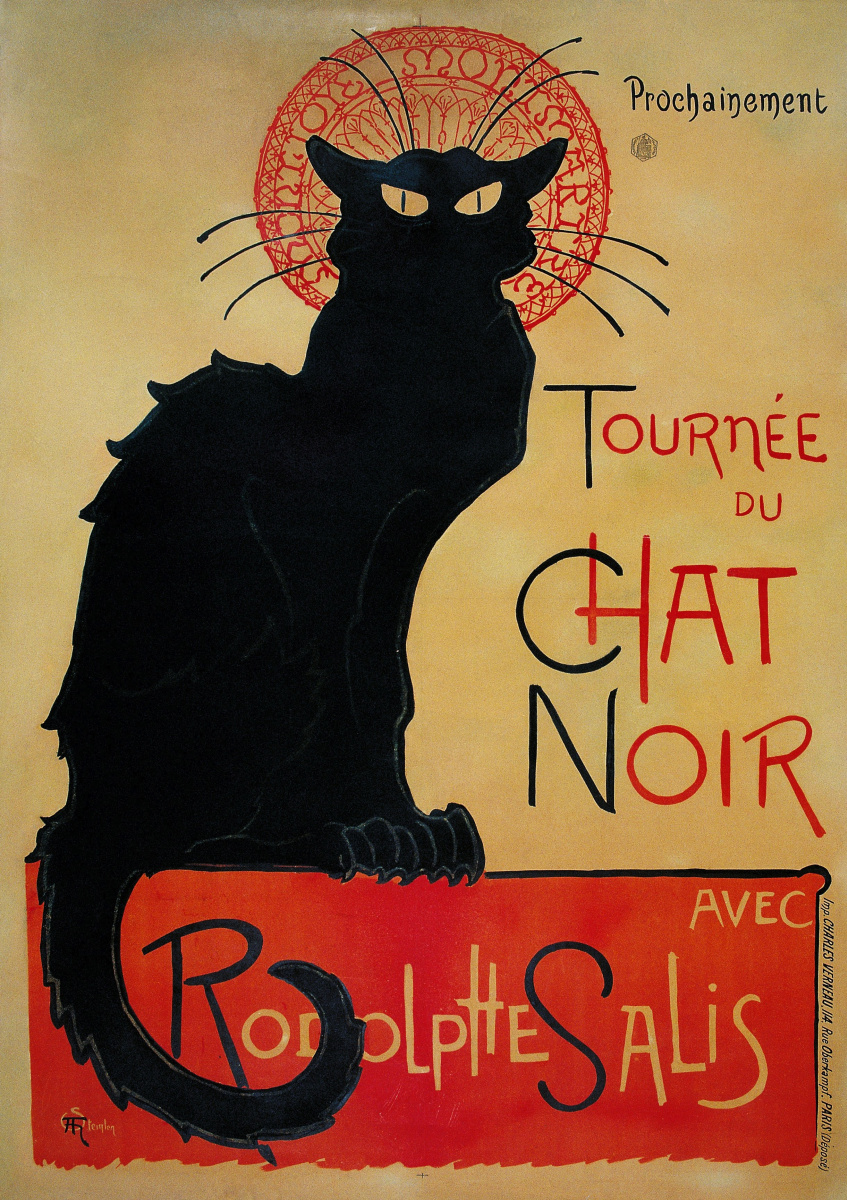

‘Le Chat Noir’

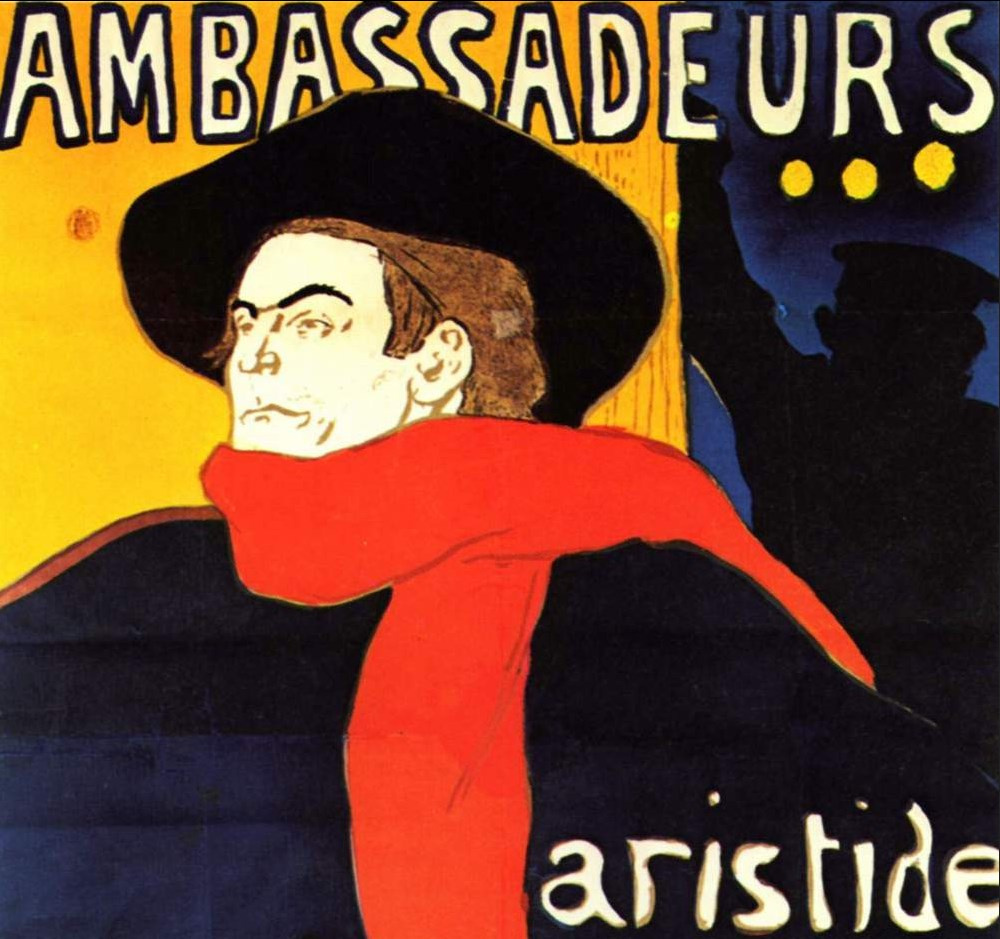

A café-concert, or café-chantant, was new entertainment in Paris. Bruant started with his chansonnettes in goguettes — this was the term for humble pubs with unpretentious audience, plain meals and drinks. There, every Tom, Dick, and Harry could sing songs with revolutionary subjects, full of most severe satire, both political and social. The repertoire of cafés-concerts (pubs with a special platform for performing) was, at first, quite scrappy, too. The customers only half listened to popular tunes and were more interested in the drinks. But by the time Aristide Bruant started singing in the cabaret Le Chat Noir, Parisians had already developed a liking for this sort of entertainment. Cafés-concerts often had their own newspapers where they featured new songs, the singers' and songwriters' names were widely known, their concerts were looked forward to, and celebrated artists made posters for them.Later, the dangerous proximity to untrustworthy and quick-tempered pimps started to be a pain in Salis’s neck. After a heavy brawl with them, he decided to relocate his respectable establishment away from that hellhole of Montmartre. Away, away! The process of Salis’s moving house was a solemn ceremony, with flags and music, it filled the night in Montmartre with shouts and light of dozens of torches. Of course, Rodolphe Salis never thought for a second that there would turn up a person crazy enough to start a new establishment on the premises of Le Chat Noir. That crazy one, though, was Aristide Bruant.

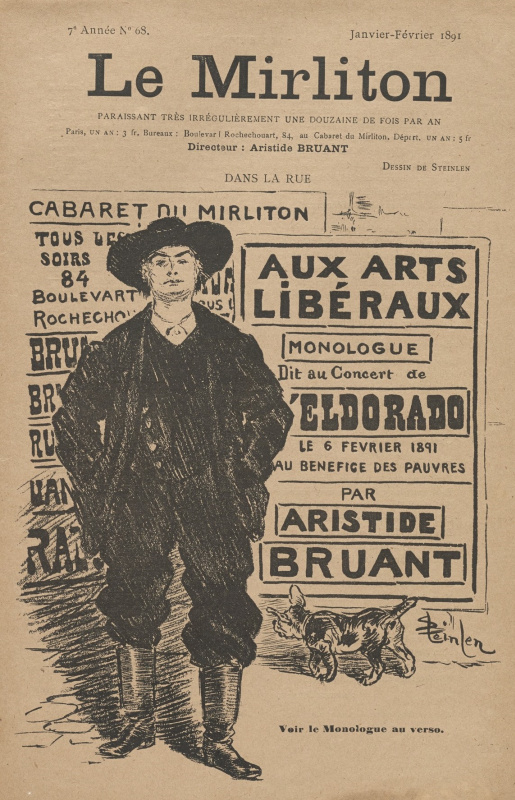

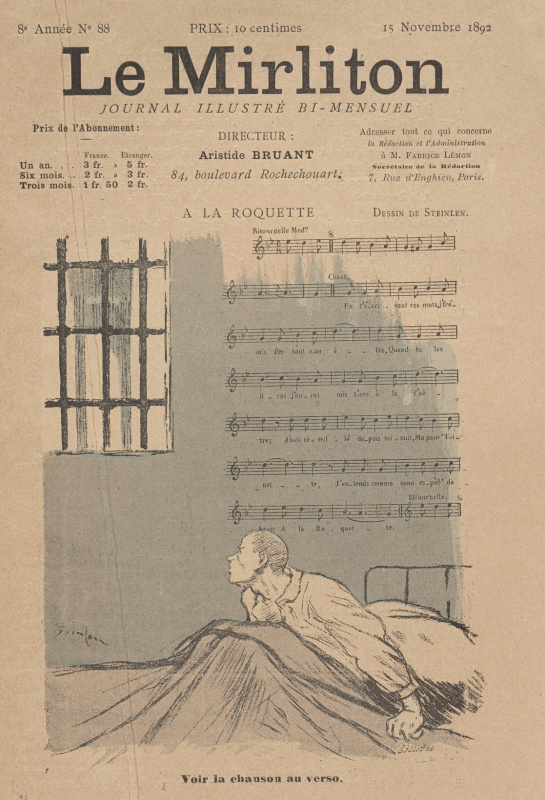

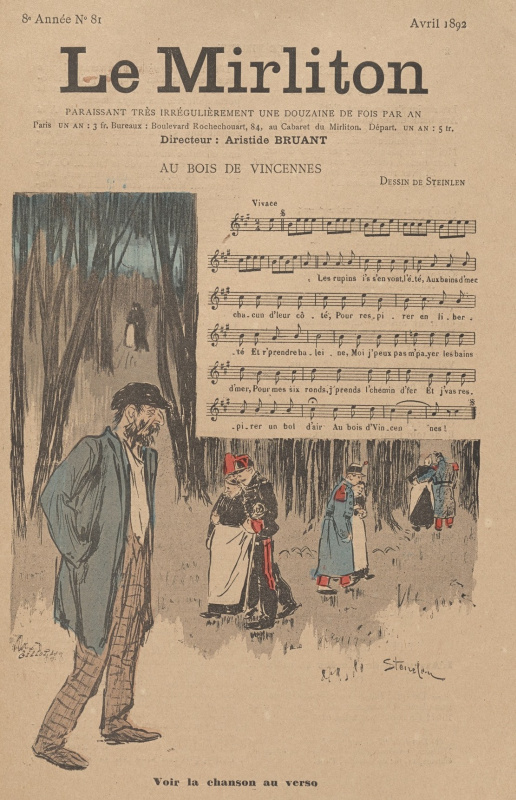

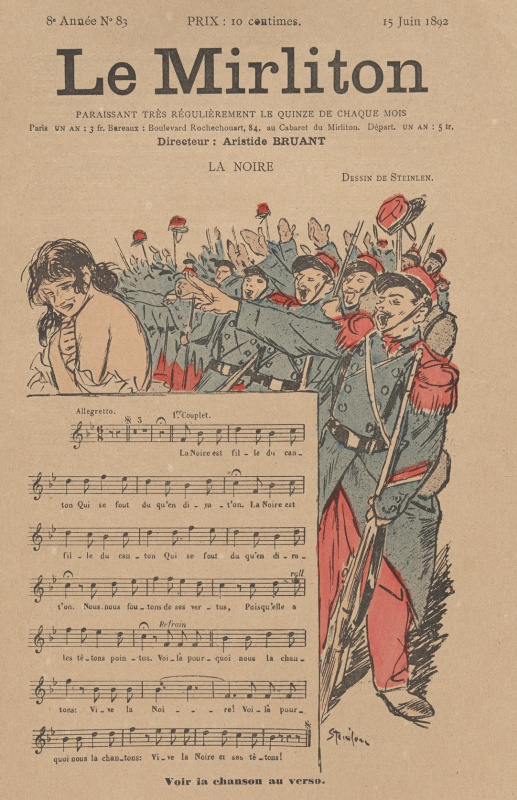

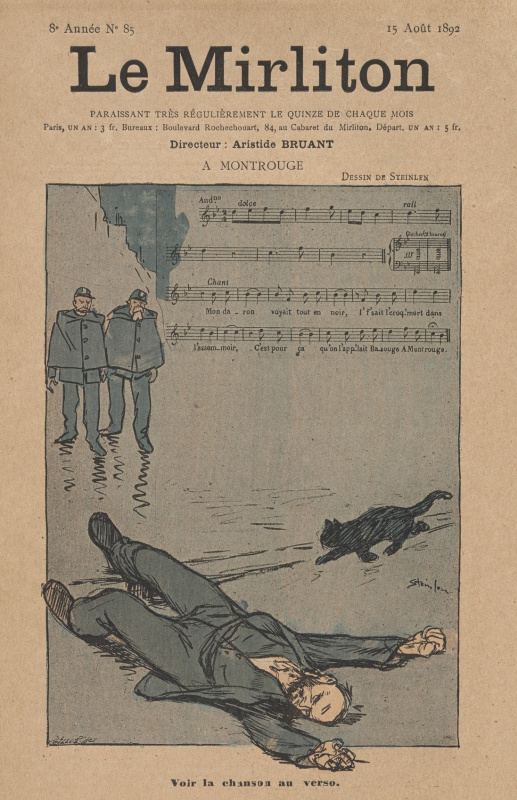

‘Le Mirliton’

Bruant invested all his savings, piled up a huge debt, and opened his own cabaret Le Mirliton in place of Le Chat Noir. But on the very first day, the cabaret was only visited by three customers, and he was raving with fury. Bursting out with the rage he had kept down so long, he gave a mouthful to a customer who was calling for the show to go on. This foul speech, however, in a most unpredictable manner, worked for Bruant’s benefit. The very next day, the customer was back to the cabaret, this time accompanied by his friends, and insisted on their being addressed with the same choicest swear words. Bruant did it enthusiastically.Since then, he would walk about among the tables, while the audience were taking places, squeezed together shoulder to shoulder, on plain benches. Now, to get inside, a visitor had to knock and be let in. Bruant would hurry them up calling each and every ‘scoundrels,' ‘cutthroats,' ‘sons-of-a-bitch,' ‘prostitutes.' Then he would get onto a table, ask the accompanist to strike the right tone, and start the concert. The only drink served in Le Mirliton was beer, and the cabaret was only open for four hours, 10 p. m. to 2 a. m. The bourgeois, all gorgeously attired, would hurry there to take their seats beside artists and prostitutes — and got more expensive beer and hotter curses.

‘… the pile of idiots who do not understand what I sing to them, who cannot understand, not knowing what it is to die from hunger, those who have come to the world with a silver spoon in their mouths,' spat Bruant, and then confessed, ‘I revenge myself in insulting them, in treating them worse than dogs. That makes them laugh to tears; they believe I joke when, often enough, it is a breeze from the past, miseries submitted to, dirtiness seen, which remounts on my lips and makes me speak as I do.'

Those of the audience who were leaving the cabaret before the concert was over came in for particularly severe treatment. The customers who chose to stay sang in chorus:

All the customers are pigs,

La fari dondon, la fari dondaine,

Especially those who go away,

La fari don daine, la fari don don!

Félix Fénéon, a reputed art critic and anarchist, who promoted divisionism, once visited Bruant’s show, left it without waiting for the programme to be over, too. Later, he commented, ‘The money that fellow used to collect in one evening during his heyday would have guaranteed a year’s work to one of our people.'

The poet of the beggars, the money-bag in spite of himself

For eight years, in clouds of smoke and the reek of beer, cheered by the motley audience’s laugh and applause, Aristide Bruant sang his songs. He was quick in writing them, and found it funny and absolutely unacceptable that serious poets could spend several months on writing a song. All those years he enjoyed the showers of gold — and finally, being stratospherically famous, at the top of his glory, he decided to leave everything behind and went on a long journey. ‘I'm really happy to be out of this cesspool!' he confessed. On his return, Bruant bought a mansion in his home village of Courtenay, and there he enjoyed fresh air and quiet. He had servants, gardeners, a guard. In his house, he had expensive carpets and furniture. He would go hunting and fishing. Adolphe Brisson, a critic, once visited Bruant’s place and wrote, ‘The poet of the beggars lives in a castle where he leads the train of a medieval nobleman.'He attempted a political career and failed. But he experienced a real triumph when he went back onstage in 1924. He was 73 then, but people still remembered his songs, and greeted him enthusiastically — him, the poet of the beggars, of all the humble, him, a symbol of Montmartre.

Text by: Anna Sidelnikova