Before the storm

Considering the list of events that happened in the life of the young Edvard Munch, you might think that he was really lucky. For the first time, he traveled to several European countries and visited all the most important museums with financial support from his first teacher Frits Thaulow. After that, funded by a state grant for artists, he travelled to Europe three times in a row and joined classes held by the influential painter Léon Bonnat in Paris. Munch was only 26 when his solo exhibition was held in Christiania (now Oslo) in 1889. He wasn’t yet 30, when the National Gallery of Norway purchased its first Munch painting, Night in Nice, and several years later — Self-Portrait with Cigarette. Four writers (who were friends) wrote a book about him.For several years, Munch spent summer time with his family in Åsgårdstrand, on the west coast of the Oslofjord, and traveled all over Europe for the rest nine months. He lived in Paris, Nice, Le Havre, Antwerp, Berlin and Copenhagen, painted portraits of famous writers, artists and composers, hanged around bohemian bars, made important acquaintances everywhere, and participated in exhibitions. What’s more, he was handsome, eloquent and charismatic.

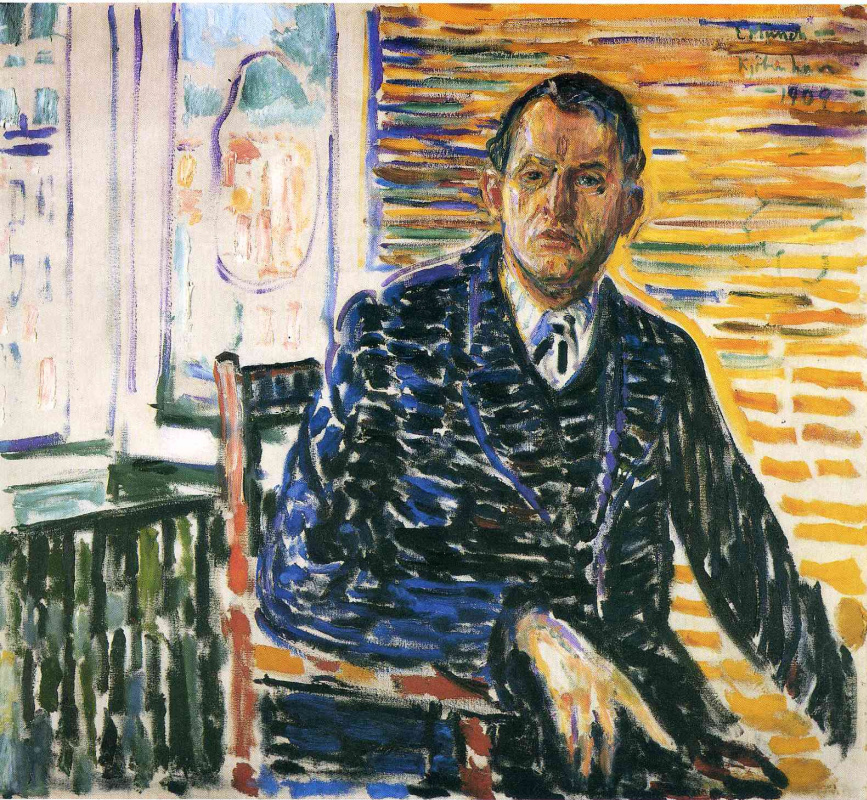

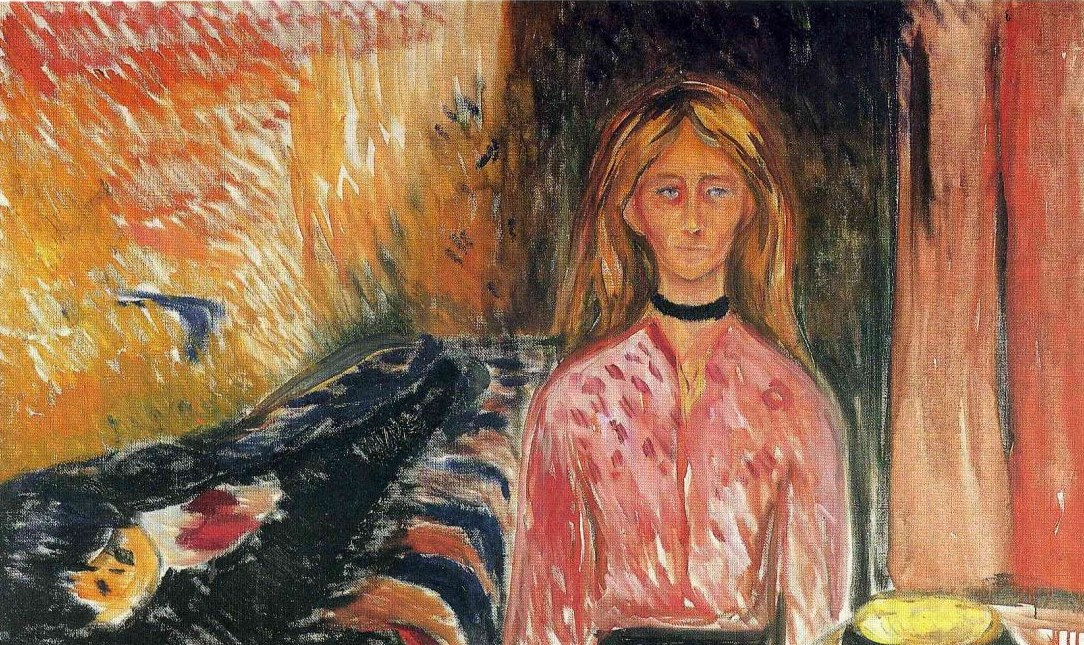

However, when you get down to this, such external success and the avalanche of good luck seem more like the higher powers' attempt to compensate for Munch’s personal anxieties and troubles. All this triumphant professional advancement was accompanied by a succession of deaths of the artist’s loved ones, protracted illnesses, time spent at sanatoriums, sleepless nights, and endless, inexplicable anxiety that had been haunting Munch all his life and eventually turned into a mania.

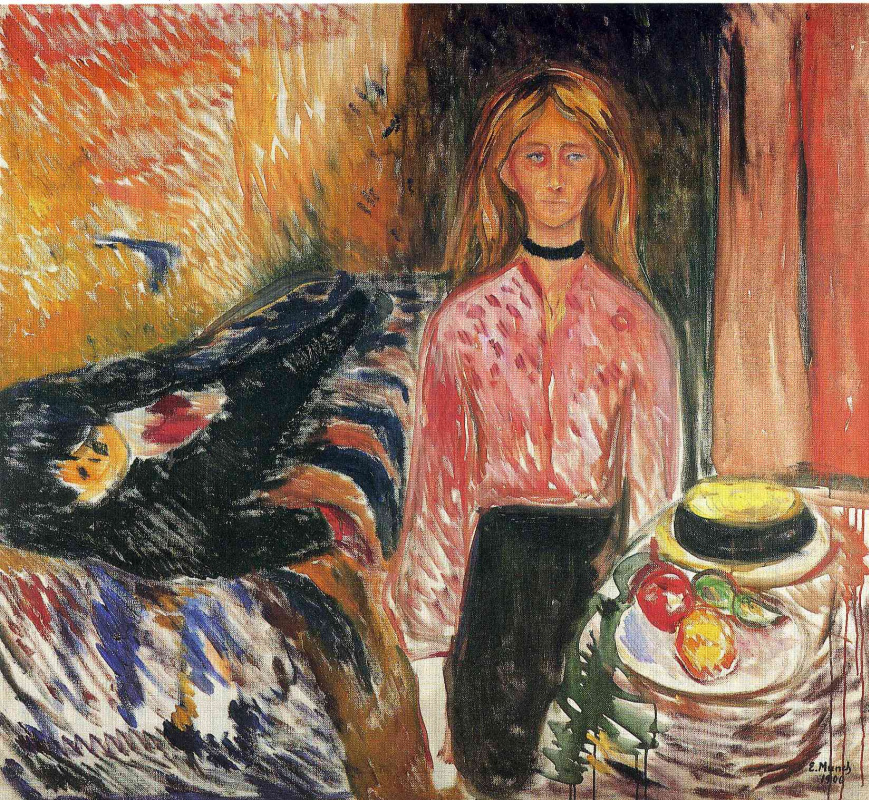

Tulla Larsen was a daughter of a wealthy wine merchant and the eleventh child in a large family. During his life, Tulla’s father earned so much that even after his death he was able to guarantee a comfortable and even quite luxurious life to his twelve children. The girl was only six when he died, so she became rich before even learning to write and read. Sure thing, she later studied English, German, math and music in a private school for girls, which was founded by the famous Norwegian folklorist, traveler and feminist Nikka Vonen, and also studied graphic art in Berlin. But after returning home to Norway, she used her knowledge the way the wealthiest women of that time did — by beautifying and diversifying noisy bohemian artistic meetings of Christiania with her educated speeches.

It will hurt

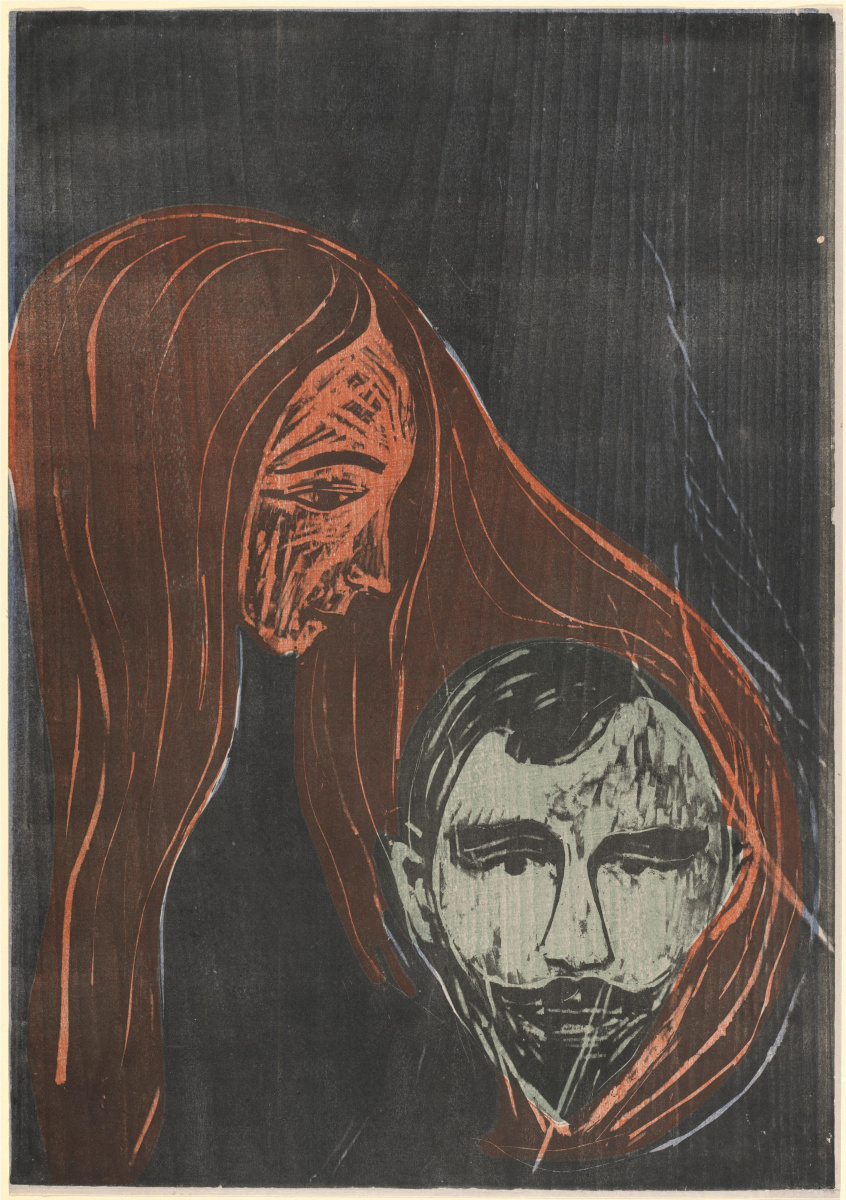

Edvard Munch was apprehensive about women (if not terrified of them). He believed that women deprived men of creative energy, sucked life out of them, just like vampires, and there was nothing more disastrous for a man than a touching love affair. You have to give him credit though: he did not even try to hide his take on the matter from Tulla Larsen, and never pretended to be a caring, tender lover (even at the height of their love affair). He gave neither promises, nor unfounded hopes. He used to give it to her straight from the shoulder: "You will continuously seek an earthly happiness with me, who as I always explained to you does not belong to this earth."Moreover, the researchers of Munch’s epistolary heritage from the artist’s house that is now a museum suspect that he deliberately treated Tulla neglectfully, rudely, and sometimes even aggressively. Just to alienate her and demonstrate that no good could ever come from him. However, the unyielding Tulla didn’t give up. Even when Munch wrote in one of his letters that she could start making etchings. He would even buy books for her, so that she could educate her spirit which was "not developed in the least".

It’s difficult to say now what kept Tulla close to a man who took care of her spiritual growth so belligerently. It looked like she was an explosively passionate, impulsive, and perhaps even reckless and irrepressible person. Her whole four-year affair with Edvard Munch satisfied their common needs for feelings that were on the verge of unbearable, painful, and extremely dangerous to health. But, of course, these two were happy quite often. Tulla and Edvard often traveled together, drank a lot, talked, argued and quarreled. And yet, he was constantly trying to find a way out of that relationship, and she was constantly trying to keep him next to her. Therefore, he was often off for a long time on his own: participating in exhibitions, studying Raphael in Rome, living in Berlin or Paris for several months, or treating his innumerable illnesses in sanatoriums during winters.

Despite their on-and-off and predominately brief meetings, relationships between the lovers ignited like the sky in Munch’s landscapes. Reproaches, threats, persuasion, blackmail — all this flew in thick mail envelopes from Christiania to Berlin, and from Paris to Christiania. The clouds grew heavier — the storm was coming. All the dangerously loaded guns that hung on the walls of their love nest were about to fire volleys at the same time. And the storm did come. And the guns did fire, just as expected.

Munch's finger

A tiny episode in Munch’s life, one scandalous scene of a break with a woman, has become almost legendary in all his biographies. Getting by with a not-so-wide range of facts (Munch was reticent about what really happened between them), biographers, critics and journalists from glossy magazines keep coming up with their own fight scenes and writing Hollywood-worthy scripts. Some of them, like British art critic Robert Hughes, took a different approach and labeled the artist with diagnoses while claiming that, like any neurotic, he exaggerated his own suffering, craved public attention and romanticized his own sacrifice.Well, it’s time for the scandalous scene of the break itself. Edvard Munch' trips to Europe became more frequent and long. He and Tulla rarely met, the tone of his letters became annoyed and dissatisfied. Although it would seem that nothing could beat the recommendation to educate her spirit.

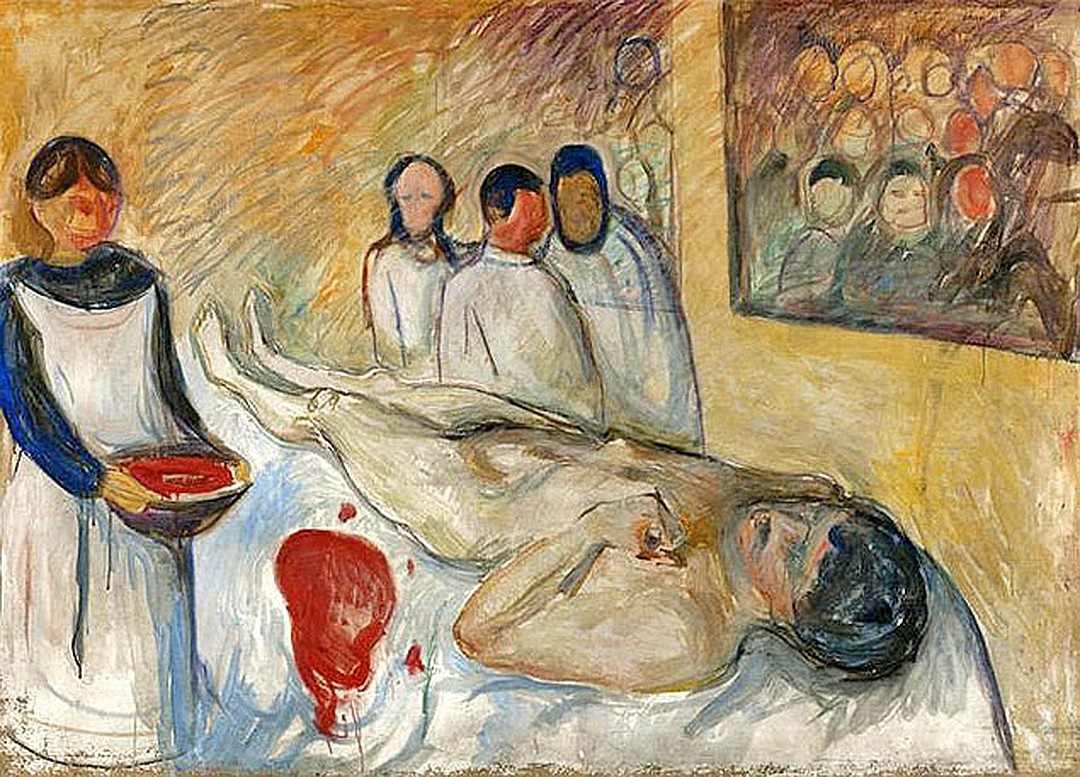

On August 23, 1902, Munch received a letter from his friend that said that Tulla tried to commit suicide. Doctors who came to help her found two empty bottles of morphine at her bedside. He came to her the following day, refused to talk about their shared future, allegedly because of her weakness and inappropriate condition for difficult conversations. Munch promised that he would go to Berlin (work, exhibitions) for a short while and on his return, give Tulla that serious conversation she insisted on having.

The last thing Tulla did in Munch’s life was calling a doctor for him. They never saw each other again. But both survived and lived very long lives apart.

After the shot

A year later, Tulla married the artist Arne Kavli, who was 10 years younger than her, and who painted tender, touching portraits of his wife. Seven years later they divorced, but she got married again the same year — and lived with her second husband for 10 years. That’s all we know about Tulla’s life: after the break with Munch, the secular chronicles and art historians were no longer interested in her.

A ridiculous injury, no more complicated than an ingrown nail, appeared to be much more complicated. Liters of lost blood, which he so persistently painted for several years after his break with Tulla, turned out to be a metaphor of the vitality which he was losing bit by bit, and the peace of mind that slowly left him.