The 16th century trends

Vittoria Colonna was born in 1490/1492 (the exact date is unknown) near Rome and was the heiress of an ancient, noble and very warlike family. When she was four or five, she was betrothed to Fernando (Ferrante) Francesco d'Ávalos, Marquis di Pescara, grandson of a Spanish military leader who moved to Naples after King Alfonso V.

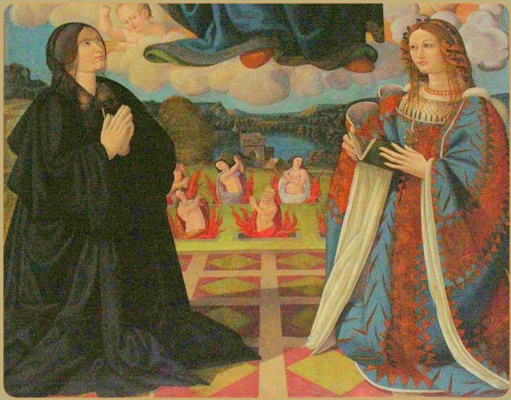

Constanza d'Ávalos and Vittoria Colonna. Fresco from the monastery of San Antonio on the island of Ischia.

She lived and grew up in the family of her future husband thenceforth, on the island of Ischia near Naples. They played and learned to read and write together, under the strict guidance of the elder (almost 30 years older!) sister of the young bridegroom, Constanza d'Ávalos, Duchess of Francavilla. She loved art, and poetry at that time was the trend among the court nobility of Naples. Constanza organized a kind of "hobby club", having gathered writers, and did everything to catch the interest of her educatees with poetry. Young Vittoria was among its most active participants.

Aragonese castle on the island of Ischia. Engraving, detail.

At the end of 1509, when the girl was seventeen (or nineteen) years old, the wedding with Fernando took place. The marriage of convenience turned out to be a union of love. In any case, Vittoria recalled later the short time spent together as the best period in her life. Perhaps it’s all about the right "dosage".

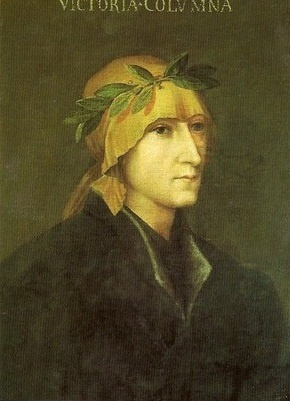

Portrait of Vittoria Colonna

Exquisite sadist

According to his contemporaries, Fernando was an intellectual, possessed of exceptional dexterity, which he showed during knightly tournaments, and a beautiful appearance. "His beard was chestnut-coloured, his nose was aquiline, his eyes widened and burned in moments of excitement, but at ordinary times they were meek and gentle," wrote his biographer Bishop Giovio.

Since the war itself was the point of life of Fernando d'Ávalos, during his service as a condottiere (the leader of mercenary military detachments), he fought both on the side of the Italians and on the side of the Spaniards against the French-Venetian army. Indeed, despite the fact that he was born in Naples, he always felt like a Spaniard and even spoke his native language with Vittoria.

Titian. Alfonso d'Ávalos, Marquis del Vasto, in armour with his page, 1533

Nevertheless, Vittoria bound herself with a sort of a vow: since she did not have her children, she adopted her young relative, Alfonso del Vasto, who was her friend for all her life.

The first lady of the Renaissance

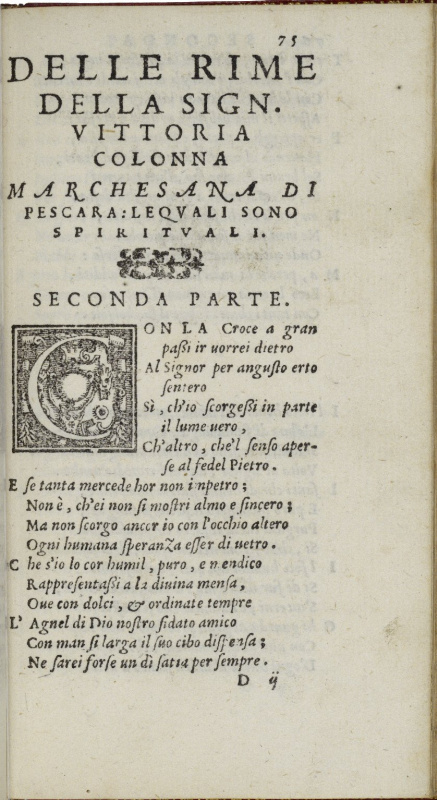

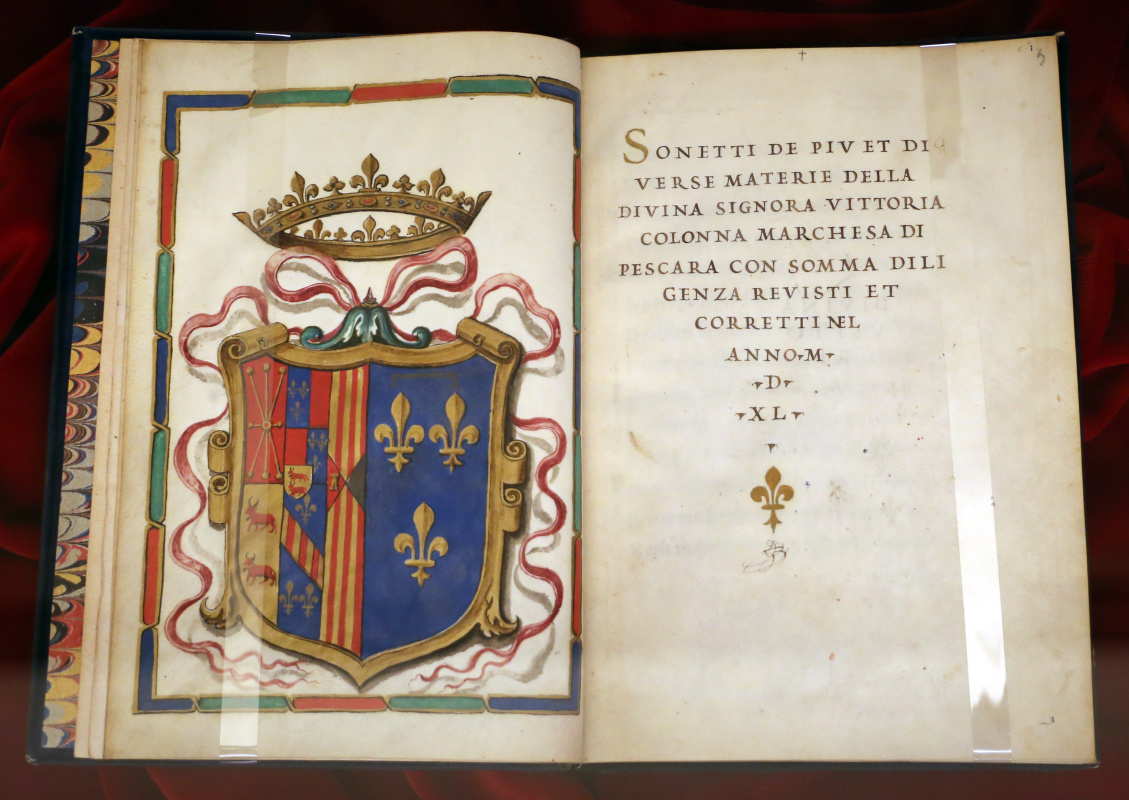

Vittoria did not lack admirers either being married or after the death of her husband (by the way, this event aroused her poetic talent). "I write only to pour out the innermost suffering that feeds my heart, which does not want any other food," this is how the first of its elegiac sonnets begins.

Vittoria Colonna, Marquise di Pescara

1520−1525, National Museum of Art of Catalonia.

Portrait of Vittoria Colonna, Florence, Uffizi Gallery, the Giovio Series.

The Giovio Series is a series of 484 portraits collected by the historian and biographer Paolo Giovio in the 16th century.

The style of the Colonna’s poems was unanimously recognized as elegant, their content was deeply thought out, although the sonnets themselves were not too emotional. However, after the first publications, their fans sought to get their copies. Among her loyal readers were cardinals, bishops, poets, scholars, diplomats who spread the works from hand to hand and even made the subject of their correspondence with the "divine poetess".

Poets of the 16th century glorified her beauty, writer Baldassare Castiglione talked about "her divine intellect", and artists hastened to capture the "most beautiful woman" on their canvases.

Raphael Sanzio.

The Parnassus fresco.

Art historians found Vittoria among other Italian poets on Raphael’s famous fresco Parnassus painted in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican.

Titan and Colonna

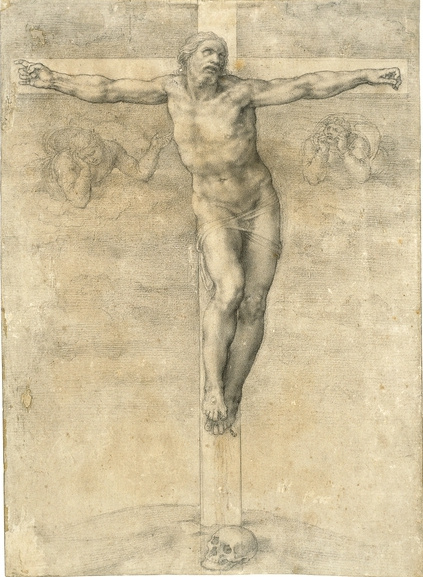

One of her contemporaries called Vittoria "an approaching column that stands in the midst of a raging storm". Thus, he emphasized not only her talent to unite people around herself, but also the fact that she resisted during the Inquisition, despite the dangerous reputation of the reformist movement leader. Vittoria sided with those theologians who opposed the tough scholasticism in the official church: many of them died at the stake, others fled. Colonna remained alive, although under the supervision of the Inquisition. Michelangelo was also considered a violator of traditions, because many of his works aroused the clergy anger and were censored. In a word, they had much to talk about.Here is what the Michelangelo’s biographer Ascanio Condivi writes about their relationship: "The love that he had for the Marquise di Pescara was especially great. He still keeps many of her letters, filled with the purest, sweetest feeling. He wrote many sonnets for her, talented and full of sweet longing." But this is not the whole picture: in one of the messages, Michelangelo criticized her for … her love of jewelry. In his opinion, she did not need this: "Jewelry, necklaces, flattery, gold, feasts and pearls! Who perceives this dummy when she creates divine things?"

According to Giovio, Michelangelo was fascinated by the marquise’s hermaphroditic features — a "slightly masculine decor" - and he "would like to transform his body in one eye in order to fully admire her appearance".

"Vittoria had one hundred and three sonnets in parchment tied together, which she sent from Viterbo," Michelangelo said on 7 March 1551, in a letter to his nephew Leonardo. He meant the poetic messages dedicated to him, which the maestro kept as a treasure.

It is generally accepted that Michelangelo had just platonic feelings for the Marquise. Some researchers believe that in this way it was easier for him "to satisfy his raging desires by passing them on to Saint Vittoria Colonna, a woman whose chastity did not threaten his unnatural homosexual instincts" (a hint of his relationship with his young student Tommaso Cavalieri, and not only him). Others argue that "thanks to Tommaso, he finally comprehended the neoplatonic theory of love by Marsilio Ficino, who declated that "selfless love for another soul (in this case, another man) helps a person to approach the Almighty".

Michelangelo.

Portrait of Tommaso Cavalieri.

Seeking at least to be not all unfit

For thy sublime and boundless courtesy,

My lowly thoughts at first were fain to try

What they could yield for grace so infinite.

But now I know my unassisted wit

Is all too weak to make me soar so high;

For pardon, lady, for this fault I cry,

And wiser still I grow remembering it.

Yea, well I see what folly 'twere to think

That largess dropped from thee like dews from heaven

Could e’er be paid by work so frail as mine!

To nothingness my art and talent sink;

He fails who from his mortal stores hath given

A thousandfold to match one gift divine.

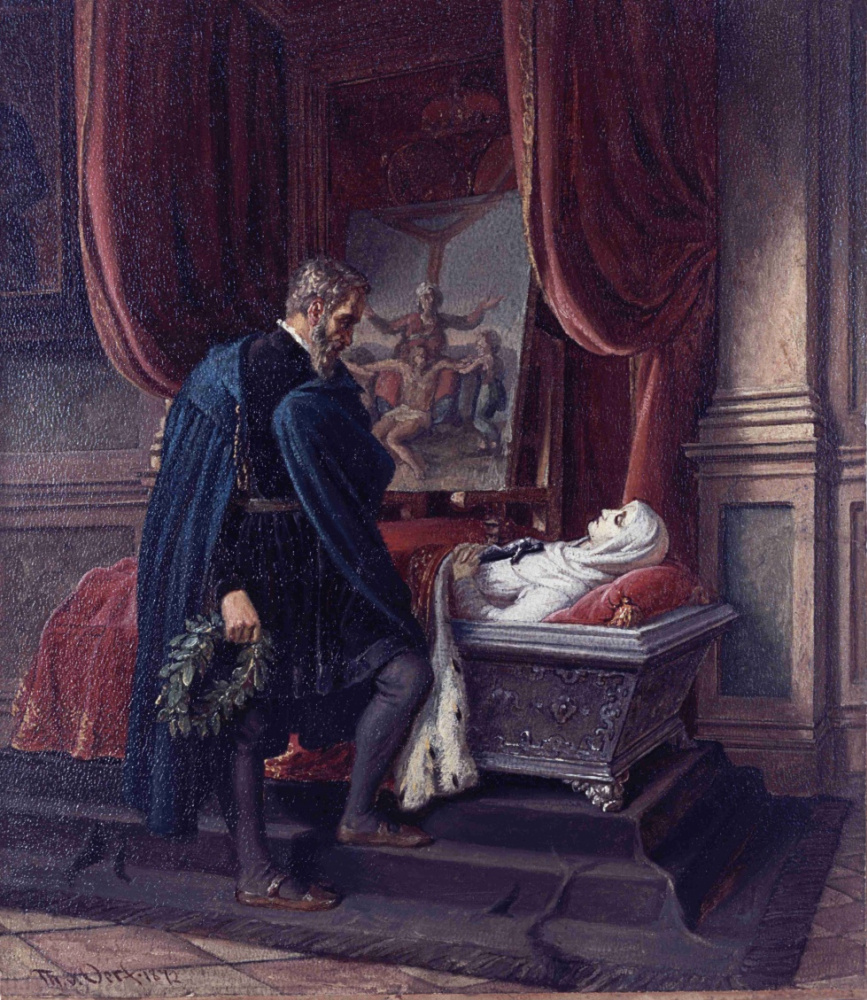

Michelangelo at the tomb of Vittoria Colonna, 1872

Museum Abtei Liesborn

"When she who gave the source of all my sighs

Fled from the world, herself, my straining sight,

Nature who gave us that unique delight,

Was sunk in shame, and we had weeping eyes."

"Death took my great friend from me," he said.

Vittoria herself, foresaw her imminent end and was not afraid of death: in the other world, she believed, her husband and the infinite happiness of divine love were waiting for her.

"For a long time I loved the world blindly,

Allured by fame, that viper at the breast,

And what emerged? on my tongue a cry of

Ceaseless wretchedness. So I turned to God —

And help came. So now I’ll write, but with nails

From the cross. His dear blood will be my ink;

His exhausted body, my streaked paper:

May I channel the grief all have known, all

He suffered, into these poems."

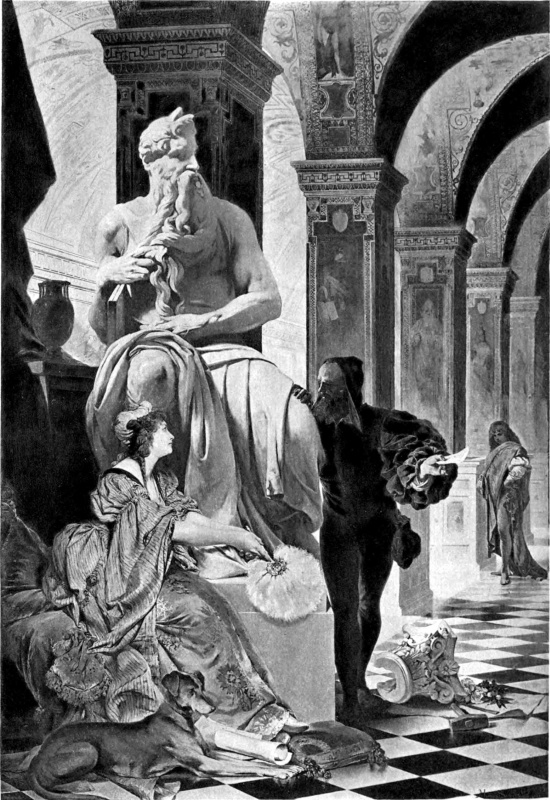

Hermann Schneider.

Vittoria and Michelangelo at the "Moses", until 1894

However, there is also such an opinion: the legend creators "made Vittoria Colonna play the role of Juliet in Michelangelo’s life drama, and this relates one of the most influential women of the Renaissance to a simple object of desire". So the British Michelangelo’s biographer John Addington Symonds believed, assuring that the influence of Colonna on the painter’s life is greater than if she were only his model or mistress. "She changed his attitude to religion, she patronized his work and served as one of the closest proxies," the researchers say today. After all, she was not just a donna who wrote poetry, but a free (in her views as well) woman. Of course, as much as a woman of the Renaissance could be free.

Jules Joseph Lefebvre.

Top center description: Diva Vittoria Colonna, ca. 1861

Vittoria did not live long, she did not live to be sixty, but she was a witness and participant in many historical events of that time. This gave rise to Rami Targoff, the author of the book about Colonna, to call her "Forest Gump of the Renaissance": she was not only the first woman whose works were published in Italy, but also the first lady to be posthumously judged by the Inquisition for reformist ideas, while Vittoria was a righteous Catholic for all her life.