Ross King (born July 16, 1962) is a Canadian novelist and non-fiction writer now living in Woodstock, England. He made his name on books that analyze certain masterpieces and events in art history. His list of books written includes volumes about Florence Paintings & Frescoes, Michelangelo Buonarroti painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and the birth of Impressionism.

Color revolution of da Vinci

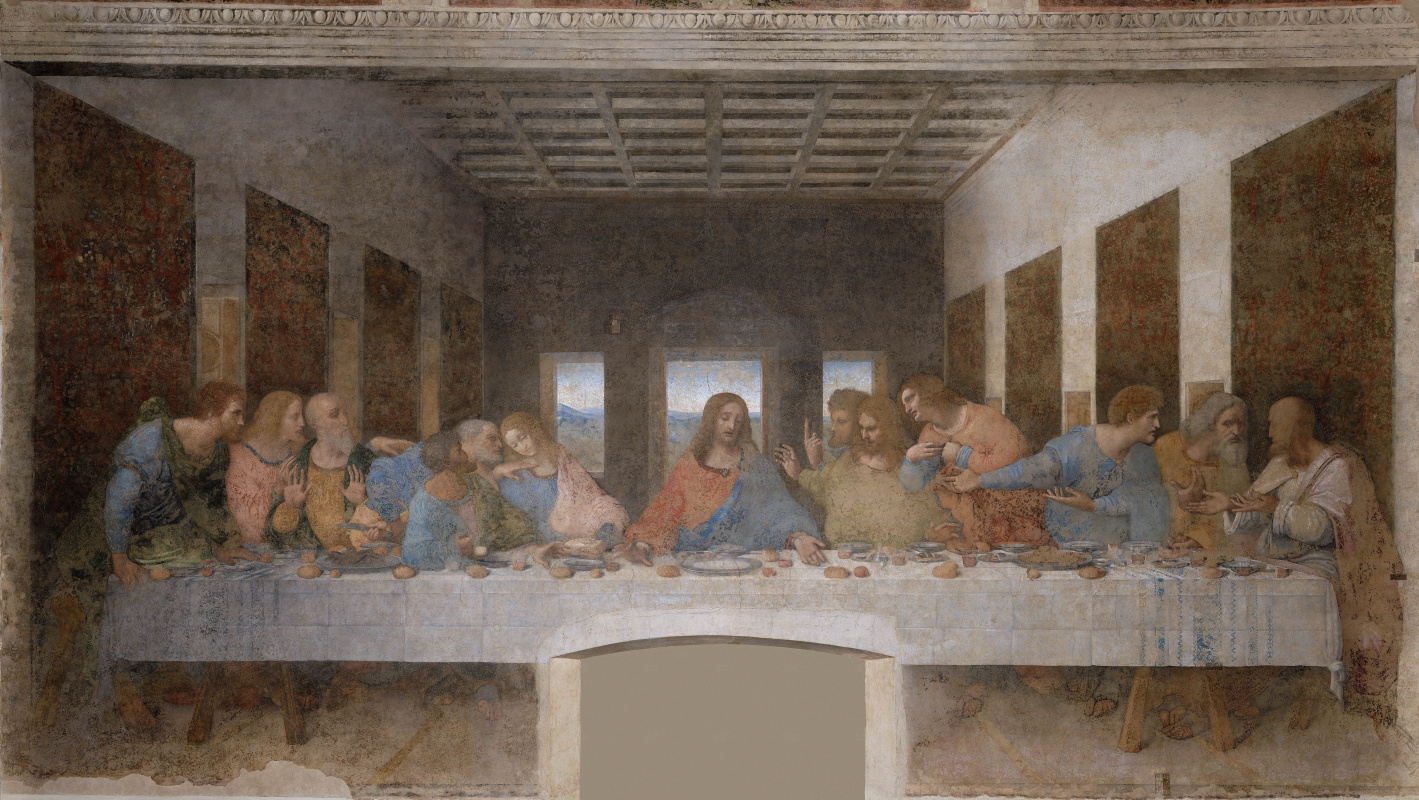

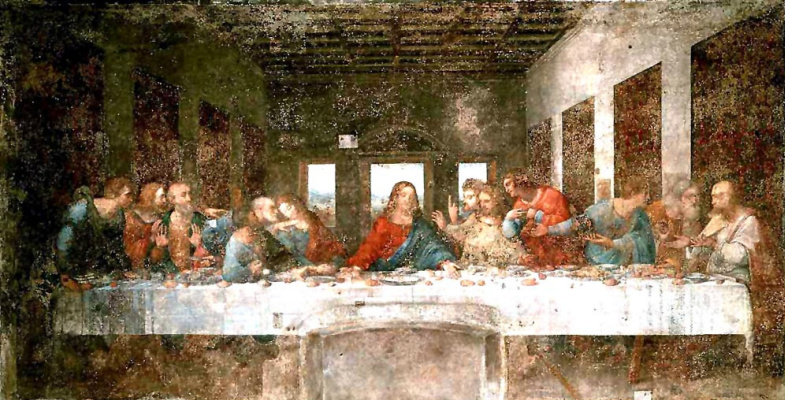

When creating frescoes, artists should follow a special method of painting water-based pigments on freshly applied plaster. But it tied their hands for they should use only those pigments that endure the impact of lime plaster. Those were not the brightest hues: as umber or ocher, for example. Leonardo did not like to put up with the restrictions, he wanted to get brightness at all costs — such as made by mineral pigments, not capable of resisting lime: ultramarine, azurite and cinnabar.Experiments with paints' composition for The Last Supper, in fact, destroyed the fresco of Da Vinci. Well, this is a widely known fact (you can read about the decay of the mural during Leonardo’s lifetime in the abstract).

Curiously, in search of a way to make colors as bright as possible, the artist managed to discover the law of complementary colors. A few centuries before the Frenchman Michel-Eugène Chevreul invented his color model in 1839, which now is the basics of drawing, Leonardo pondered on how the saturation of these or those hues varies upon the colors next to them.

The fact that shadows are not black and not gray, but they change hues depending on different conditions, was a revolutionary idea in those times, impossible to understanding by contemporaries. But Leonardo went even further, developing a composition to depict a blue shadow: a mixture of shellac (resin of orange hues, secreted by the females of certain insect-worms) and verdigris, a bright bluish-green encrustation of copper carbonate. These colorful "impressionistic" shadows can be found on The Last Supper.

Not every section is golden

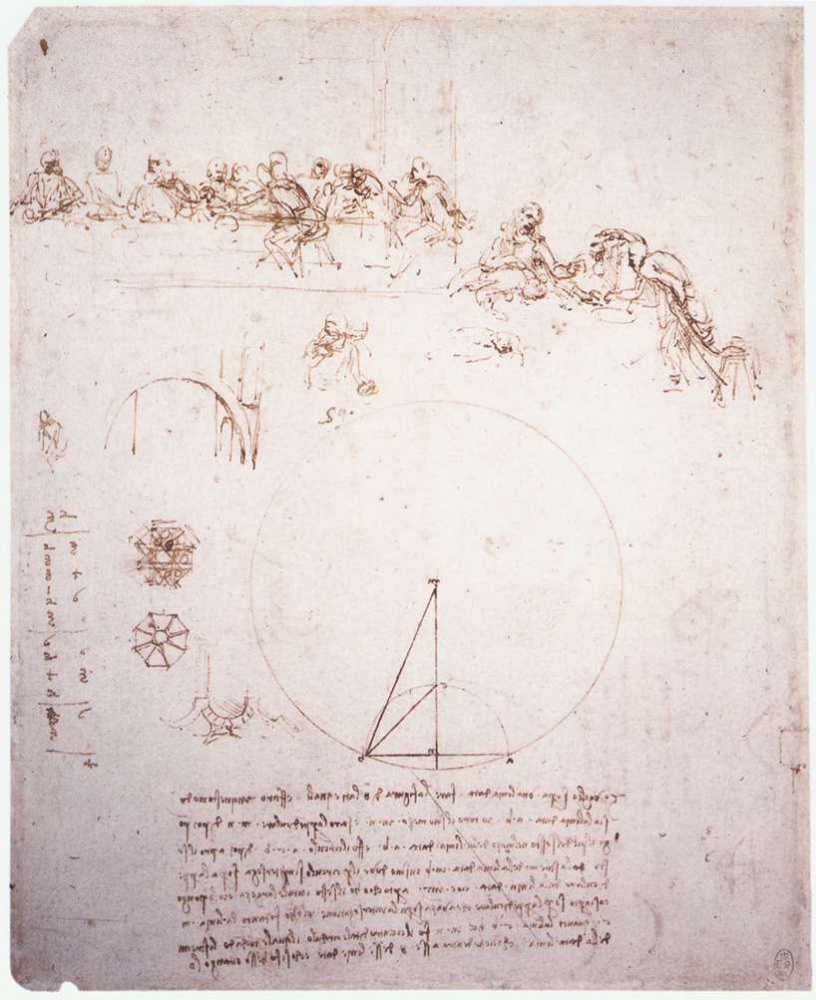

Often, researchers explain harmony of space and composition in Da Vinci artwork through his applying the principle of the golden section, or, as it is also called, the "divine proportion". They support their theory, argumenting that the artist was a friend of the Franciscan mathematician Luca Pacioli, the author of the Compendium on the Divine Proportion "De Divina Proportione," illustrated by Leonardo.However, the artist has completed The Last Supper 10 years before he started working on the illustrations. And Pacioli himself has not ever declared the golden section as the key element in composing an artwork. In addition, there is no comments on the divine proportion in Da Vinci’s notes. Wouldn’t he mention it at least once, when disserting about proportions in his "Treatise on Painting," if he really saw in it the formula of ideal composition?

Musical harmony of The Last Supper

So, Leonardo da Vinci was not a follower of the divine proportion theory. Yet still the space of The Last Supper is subject to a certain pattern. One of the artist’s hobbies was creating musical instruments, and he believed that the principles of musical harmony can be embodied in the architecture.Da Vinci’s thoughts on harmony were not new—they could be traced back to Pythagoras who put forward similar ideas. An idol of Da Vinci, an Italian humanist scholar Leon Battista Alberti, also believed that musical harmonies "are able to fill the glance and mind with unspeakable ecstasy" and artists should use them in their works. Moreover, the tomb slab in honour of Cosimo de’Medici by Andrea del Verrocchio, one of the teachers of Leonardo, was created in accordance with the musical harmony.

Andrea del Vercocchio

Tomb of Piero and Giovanni de' Medici

1469−72

Marble, porphyry, serpentine, bronze and pietra serena, height 540 cm

San Lorenzo, Florence

Its symmetric geometrical forms produce musical consonance. Photo by forum.awd.ru.

Presumably, the numbers on the Da Vinci sketch reflect the ratio between the fourth and fifth parts of the octave (3:4:6), the octave (3:6) and the fifth part (4:6). If the wall of the refectory where The Last Supper is placed is divided into 12 parts, the ceiling in the foreground contains six segments, which give a ratio of 1:2 (an octave). The far wall contains 4 such parts, and the width between the center of the side windows is 3. Thus, a ratio of 12:6:4:3 is obtained-the same ratio as between the arras on the wall. Perhaps, Leonardo really tried to turn notes into music that people could see.

Was Leonardo da Vinci a heretic?

It seems that the artist was an ideal target for all sorts of conspiracy theories. Indeed, the range of his interests was so wide that not only an average inhabitant of the Medieval Europe, but also contemporaries of more enlightened epochs deemed this eccentric, eternally preoccupied with getting knowledge and various experiences, to be if not a devil worshiper, then at least an alchemist or a heretic.In fact, Leonardo has much more complex view on religion. Possessing the habit of not taking literally anything on trust, he examined everything that was in the field of his view. When embarking on The Last Supper, he acquired the Holy Bible and began to scrutinize it. His notes evidence that while reading it, he asked questions like: could forty days and forty nights of torrential rain completely cover the surface of the Earth to the level at which seashells are found, and if so, where did the water go after that, and so on.

In attempts to answer his own questions, da Vinci comes to a standstill: "Here, then, natural reasons are wanting; hence to remove this doubt it is necessary to call in a miracle to aid us…" And this is not the only example when his scientific research resulted in a conviction that some higher powers, incomprehensible by empirical means, were involved in the universe.

Leonardo owes his glory of heretic to Vasari, who in his "Lives," published first in 1550, presented the artist as an eccentric atheist who did not shrink from heretical reasoning. But 18 years later, in a revised edition of his immortal hit, Vasari reckoned Leonardo with the righteous, "…feeling himself near to death, [da Vinci] asked to have himself diligently informed of the teaching of the Catholic faith, and of the good way and holy Christian religion; and then, with many moans, he confessed and was penitent…"

Vasari’s abrupt predisposition might have been caused by the acquaintance with Francesco Melzi in 1566. Leonardo’s favorite pupil and his chief heir met Da Vinci when he was a child and was close to him until his death. Apparently, he managed to dispel fallacies of the Renaissance chronicle. Nonetheless, Da Vinci has been entrenched with a reputation of a heretic for many centuries.

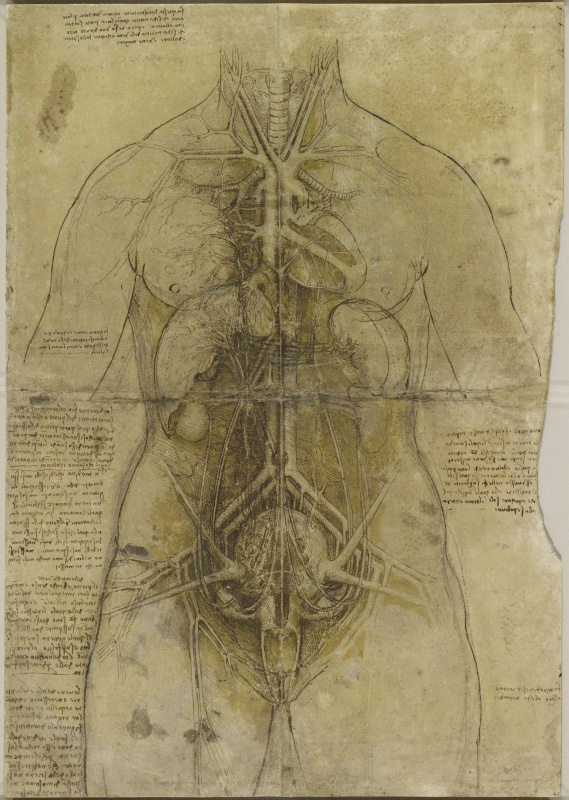

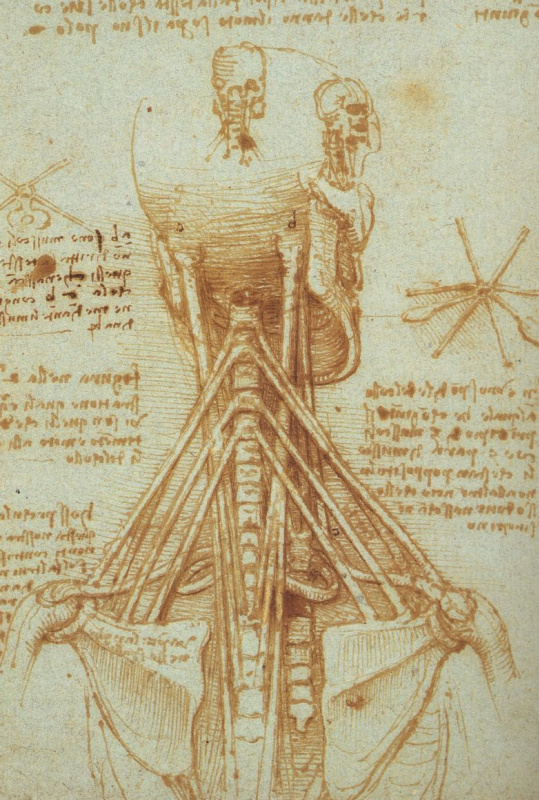

Anticlerical believer

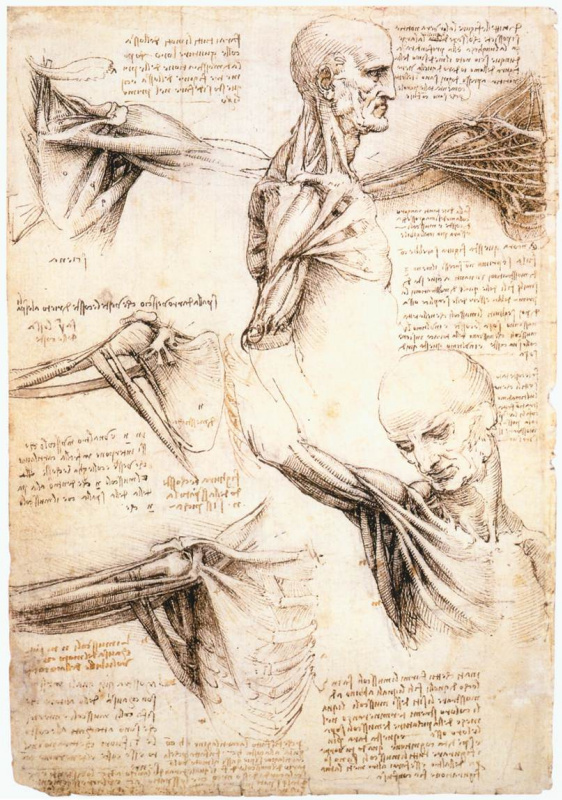

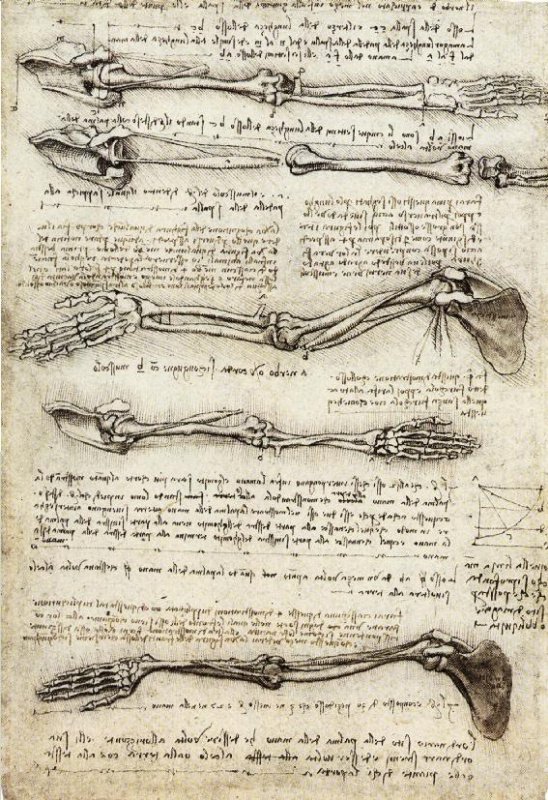

Despite how strange this may sound, Leonardo’s faith strengthened in his pathoanatomical experiments. By dissecting humans and animals, Leonardo made many anatomical and some physiological discoveries, described in a truly religious way. In his 1140 note he says about human body, "and if this, his external form, appears to thee marvellously constructed, remember that it is nothing as compared with the soul that dwells in that structure; for that indeed, be it what it may, is a thing divine. Leave it then to dwell in His work at His good will and pleasure, and let not your rage or malice destroy a life—for indeed, he who does not value it, does not himself deserve it."At the same time, Leonardo did not restrain form rejection of the institution of Church he had to face in his times. He spited his bitter criticism on its individual representatives as well as entire classes, "Pharisees—that is to say, friars." He accused clergymen in hypocrisy and composed a riddle about people who live in riches and pompous buildings and prove that "this is the way to make friends with God."

However, being a sensible man, Da Vinci did not have a one-size-fits-all approach to people. Despite his skepticism about monastic orders, he made friends with some of them, like Luke Pacioli, a scholar monk of the Franciscans Order, mentioned above.

The Key to the Da Vinci Code

All factors mentioned above, apparently, led to the situation we face now: the artist is credited with the most absurd heresy beginning with his participation in a secret order that keeps the top-secret knowledge about the Christ descendants, and ending with Mary Magdalene on The Last Supper instead of one of The Apostles.The affirmation that Leonardo was a grand master of the ghostly Priory of Sion, a secret society founded in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1099 to keep evidences of birth of a child of Mary Magdalene and Christ and transmitting them around the world, was refuted in a court. According to this theory, the direct descendants of the Savior became the founders of the royal dynasty of Merovingians ruling a certain country located on the territory of modern France and partially in Germany from the 5th to the 8th century.

In fact, this myth is only half a century old: the mysterious Priory was arranged in the 1950s by Pierre Plantard, who considered himself the last of the Merovingian dynasty (and the direct descendant of Christ respectively). He had to admit this at the French court hearing in 1993.

The fabricator made a fake list of the grand masters of the secret order, where he put names of Leonardo da Vinci together with Isaac Newton and Victor Hugo, and planted this "document" at the National Library of France. Well, the writer Dan Brown took advantage of the inexorable fantasy of the fraudster and concocted a strong bestseller, which brought him not one million in quite real American money.

Anyways who's sitting next to Christ at The Last Supper?

In fact, if Leonardo had any reasons to portray Mary Magdalene in The Last Supper, there was no need to do it secretly, in disguise of one of the Apostles. At least, because it was already done half a century before him: Fra Beato Angelico rendered a kneeling figure of Mary on a fresco in the Dominican monastery of San Marco in Florence, depicting the events on The Last Supper of Christ and The Apostles.On the contrary, he liked much more to portray androgynous figures, which can easily be attributed to both female and male sex. In this context, you can recall a young angel in his painting The Virgin of the Rocks as well as his Saint John the Baptist. Some researchers (for example, art historian Silvano Vinceti, who discovered the bones of Caravaggio in 2010) advanced the hypothesis that even the universally recognized ideal of femininity, Mona Lisa, was painted by Leonardo based on his young gay lover Salai.

If only you wish, you can find some similarities between the Gioconda and Saint John the Baptist (read the abstract to the painting to learn that Salai was a model for the latter as well) and the Apostle John from The Last Supper. All of them are united by that same mysterious smile (which, by the way, the German researchers has unraveled not so long ago).

Leonardo has not pioneered in giving feminine traits to the Apostle and Evangelist St. John. Since he was considered the youngest among the Apostles, he was often portrayed as a frail, smooth-faced and effeminate young man. So, Leonardo’s version did not go beyond the established pictorial tradition approved by contemporaries.

What do The Apostles eat on The Last Supper?

Actually, Da Vinci was the first who "gave the feast", depicting a famous evangelical scene. Most often, the last meal of Christ was painted in an ascetic way, since the original source did not provide artists with special details as to the set of dishes. Contrary to his predecessors, who showed mainly bread and wine, needed for the Eucharist (adding a small lamb, at their best), Leonardo feasted on the entire table.One of the three large common dishes in the center of the table is already empty, except for a slice of fruit (possibly a pomegranate) on its edge. However, there is a dish full of fish standing in front of the Apostle Andrew. Well, it not unexpected in any way, as it is repeatedly mentioned in the Gospel, and some of the apostles worked as fishermen before they were called by Christ. Besides, fish is one of the ancient symbols of Christ himself. In Greek, ICHTHUS stands for I=Jesus, Ch=Christ, Th=Theou (God's), U=Uios (Son), S=Soter (Savior), that is "Jesus Christos Theou Uios Soter" (Jesus Christ — the Son of God the Savior).

The last restoration of the fresco made it possible to see one more dish: the sliced eel served with orange slices. At the times when The Last Supper was made, such a delicacy could adorn the table in the most notable houses, and Ross King puts forward two versions why the artist could place such an unconventional dish in his composition.

The first one surmises that since the picture was a part of the vain plan of Ludovico Sforza, then, perhaps, Leonardo wanted to display the luxurious hospitable receptions of his patron. And the second refers to the story written by Gentile Sermini, the 15th century writer, where the dish of eels and oranges was a symbol of gluttony. The story ridiculed on a priest who hurried to finish the divine service to get home for a dinner and taste an eel cooked following a special recipe.

Anticlerical spirit of the story was close to that of Leonardo. But, on the other hand, he painted exquisite dishes on the wall of the monastery refectory, whose order’s members could eat only bread and water most of the year, or simple meals on special occasions. So it is likely that Da Vinci did not aimed on mocking the starving friars.

Silent scene: Eucharist or betrayal?

According to the Gospel, two key moments took place during Last Supper of Christ: it is not only Christ’s announcement of the forthcoming betrayal, but in equal measure the institution of the Eucharist. For a long time researches believed that Leonardo focused purely on the emotional reactions of the Apostles in response to the message of betrayal. Goethe believed in this too, as well as most American art historians of the last century.Goethe did not consider himself a Christian, and there was a progressive trend among the US art schools in the twentieth century which reject the religion in Leonardo’s painting and consider Da Vinci "the most deeply thinking scientists" of his time. Although, if we just recall his reasoning about the Creator’s role in composing a human body, one does not interfere with the other. Gradually, these very efforts of American researchers revised this one-sided view.

Following Leo Steinberg, who devoted his extensive article to the analysis of arguments in favor of the sacred content in the Da Vinci’s Last Supper, this theory was supported by his compatriot Horst Woldemar Janson, the author of a classic textbook History of Art. He noticed that Da Vinci paid his closest attention not only to the psychological drama, but to gestures of Christ, attesting simultaneous establishment of the Eucharist.

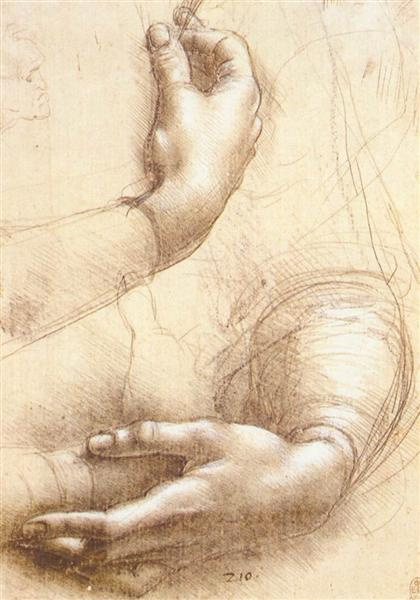

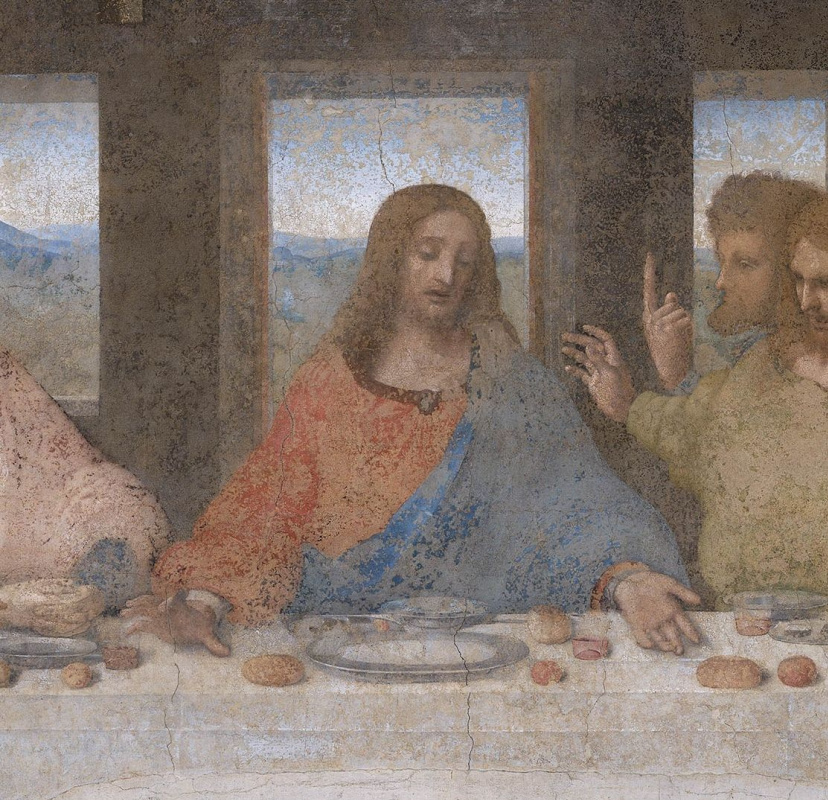

Leonardo was so concerned with an accurate representation of his concept, that he was looking for a separate model to depict hands of Christ. "Alessandro Carissimo of Parma for the hand of Christ," we read in his notes. Nobody has ever been so preoccupied with gestures as a means of expression: among the sketches of his Adoration of the Magi there are two sheets, covered with all possible positions of hands in different views. Among the rest, the hands of Christ are deliberately put in the center of the composition, forming an equilateral triangle in the very center of the painting.

While the right hand of Jesus reaches out to the same dish as the hand of Judas, illustrating the words from the Gospel of Matthew 26:23 "He who has dipped his hand in the dish with me will betray me," his left hand points at bread. The palm is opened in such a way that Leonardo’s idea appeals quite straightforward: Christ does not stretch his hand to take bread from the table, but as if blessing it for the Eucharist, "Take, eat: this is my body" (Mark 14:23).

That the Da Vinci’s Last Supper scene is culminated not in Apostles' reaction to announcement of Judas betrayal, but in the institution of the Eucharist, Christ eyes, looking directly at bread, speak eloquently. Dramatic effect has been reached by the highly emotional contrast on the mural: in the midst of a storm of indignation, bewilderment, embarrassment and other mixed feelings of the Apostles, we see the face of Christ, calm and meditative in his prayer.

"Difficult child" of Da Vinci

The tortures, which the ill-fated work endured when emerging into this world, do not stand any comparisons to what the mural awaited in the future. Leonardo’s experiment with applying pigment to a dry plaster, hoping to achieve a more complex palette, failed, and in less than 20 years, the painted surface showed deterioration. The decay was worsened by all kinds of misfortunes and natural disasters.In 1652, for some unknown reason, the monastery residents decided to make a door in the wall, "cutting off" Christ’s feet and rudely destroying the integrity of the fresco. Later, mediocre artists tried to restore the mural. One of them almost completely overpainted The Last Supper, leaving only the heads of Matthew, Thaddeus and Simon unchanged. Another restoration transformed one leg of the Apostle Bartholomew into a leg of a chair, and turned Foma’s hand into a loaf of bread.

During the Second World War, The Last Supper was saved only by a miracle: on August 16th, 1943, a British Royal Air Force bomb hit the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Only the precaution had prevented Leonardo’s masterpiece from collapsing. In 1940, local art officials had installed sandbags, pine scaffolding, and metal bracing on both sides of the north wall of the refectory.

The ruins of the refectory of the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie after the August 15th Allied bombing. The Last Supper is hidden by the protective construction (photo from the book).

As a result, The Last Supper became world-famous largely due to its state of decay. Writer Henry James called it "the saddest work of art in the world" and "an illustrious invalid whom people visit to see how he lasts, with leave-taking sighs and almost death-bed or tiptoe precautions."

At the same time, it was this very mural that made Leonardo a recognized genius: the rest of his artwork was unavailable for public until almost the beginning of the 19th century, when Mona Lisa came out from the bedroom of Napoleon and went to the Louvre. The Last Supper was the only evidence of Da Vinci’s talent open to public for three centuries after his death.

Written by Natalia Azarenko