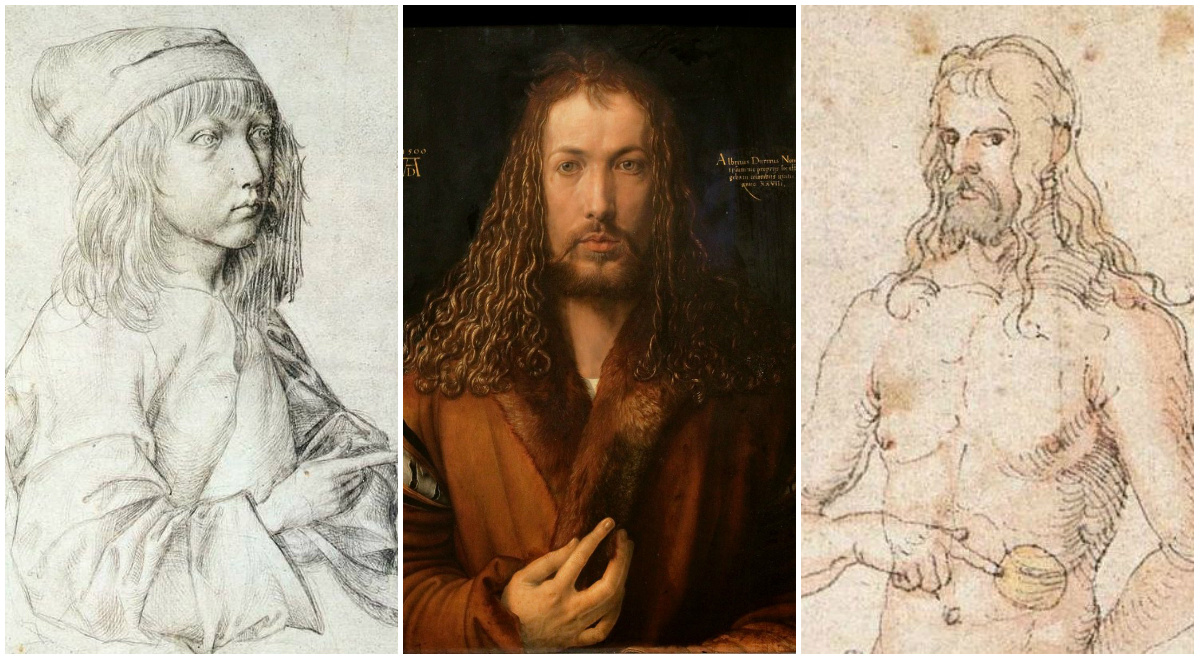

The earliest self-portrait by Dürer at the age of 13.

Sometime later, he wrote in the upper right-hand corner: "This I have drawn from myself from the looking-glass, in the year 1484, when I was still a child — Albrecht Dürer." In Germany, the self-portraiture was not usual in late 15th century. 13-year-old Dürer could not see any samples nor could he assume that, thanks to him, the self-portraiture would become a separate genre in European art someday. With curiosity of a scientist, so typical of the Renaissance , Albrecht simply presented the object he was interested in-his own face-not trying to beautify himself, nor making a hero of himself, nor dressing himself up. This would come later, when he grew older.

Famous art historian Marcel Brion describes the artist’s first self-portrait in his "Albrecht Dürer: His Life and Work": "His features, in the drawing, are most attractive: the plump cheeks have a boyish, ingenuous grace. The wide eyes are full of passionate and touching enquiry. They protrude like those of birds of prey, which can look straight into the sun without blinking. The drawing is oddly clumsy, more so than in any other of his works. The silver point, well suited to the meticulous precision required in delineating jewellery, here traces the curve of the eyelids and the highlight of the pupil in a sharp, emphatic line. The resultant gaze has a wild character, almost suggesting hallucination. It may be due simply to the unpracticed hand of the young artist. But it is also possible that he already possessed that amazing insight into the depths and peculiarities of his own character which he showed later. The face is presented in three-quarter profile, thus giving prominence to the tender smoothness of the full cheeks and the brief, aggressive arch of the beak-like nose. Despite the traces that still remain of some softness and even formlessness in the modeling of the flesh, the nose and eyes are so drawn as to indicate a complete maturity in the subject. The boy looks self-confident, already in control of his faculties and his fate."

At first glance, the Self-Portrait with a Study of a Hand and a Pillow seems a bit of caricature, a kind of a friendly cartoon of himself. However, there is no need to find a hidden meaning in it, it was just a study in drawing. Dürer exercised in creating fully 3-D objects by using hatching and in analyzing how the lines represented their deformations. On the self-portait's verso, he has penned the changing forms of 6 pillows layed in different positions.

Dürer paid close attention to hands as well as face. Being a wonderful draftsman, he consider hands one of the most interesting objects to study and depict. He never drew them in general, but always in detail, working on skin relief, its smallest lines and wrinkles. For example, a sketch for his altar image Betende Hände (Praying hands) is known as a separate work Studie zu den Händen eines Apostels (Study of the Hands of an Apostle), 1508. By the way, his thin hands with long tapering fingers were considered a sign of high spiritual perfection at Dürer's times.

Professionals in the art field think his early self-portraits are full of "concern, anxiety, and self-doubt." They already have a certain emotional peculiarity which is present in all his later self-portraits: there is none, where he portrayed himself joyful or at least having a hint of a smile. It is partially a tribute to the tradition-no one laughed in medieval art-and it reflects his character as well. Dürer inherited his father’s family trait, the habitual silence and gloominess. He had a complex character full of tense thinking that was always dissatisfied with himself. His famous engraving Melencolia I (Melancholia) by Albrecht Dürer, 1514, quite often is referred to as his spiritual self-portrait.

Self-Portrait of the Artist holding a Thistle, 1493.

While Dürer was traveling near the Upper Rhine and improving his skills, he got acquainted with famous artists and sketched views of cities and mountains. At the same time, his father betrothed a bride for Albrecht. He mentioned the courtship as a fait accompli in a letter to his son when Dürer was in Strasbourg, suspecting nothing of this sort. There was hardly anything written about the girl in a letter but plenty about her parents. The future father-in-law, Hans Frey was a famous craftsman of interior fountains and was about to be appointed to the Grand Council of Nuremberg, and the mother-in-law was born in a patrician (though impoverished) Rummel dynasty.

Dürer the Elder was a son of Hungarian peasants, and he wanted so much to make a good match for Albrecht! So, he demanded his son to finish all his affairs and return to Nuremberg. Meanwhile, he also must paint and send his own portrait to Agnes so that the bride could imagine how her groom looked like.

Portrait of the Artist holding a Thistle, 1493, referred to as a kind of preview in Dürer's family life. It was painted in oil not on a wooden panel, as portraits were at that time, but on vellum. Probably, in such a way it was easier to send a portrait. The image was pasted on canvas only in 1840. Dürer was 22 years old at that time. His goal was not to study himself but to show himself to others, to demonstrate his outlook and personality to the world. It was a challenging experience for Dürer and he has fulfilled the order with an artistic enthusiasm. He displayed himself in a calling, carnival and theatrical elegance: his transparent white shirt was constricted by the pinky-purple cords, the sleeves of his outer dress were decorated with cutouts, and extravagant red hat looked more like a dahlia flower, rather than a headwear.

Dürer holds an elegant thistle which brings two rivaling theories. In botany, the flower is named Eryngium amethystinum, the amethyst feverweed, or a 'blue thistle'. Some scholars believe that the thistle represents the crown of thorns from Christ’s Passion. Hence, Dürer shows his symbol of faith. The rival theory is that the thistle is called ‘Männer treu' in German, which also means ‘husband's fidelity.' So, Albrecht makes it clear that he was not going to object father and promises to be a faithful husband. In any case, the artist’s inscription 'My sach die gat / Als es oben schtat' reads, "Things happen to me as it is written on high." It can be interpreted as an expression of resignation to the destiny and parents' will. However, his suit blurts out: "I will do as my father tells me, but that does not prevent me from being myself and choose my own path."

Self-Portrait of Dürer, the Magnificent in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

By the moment Albrecht has painted it, he had recently came back from his second trip to Italy. In Northern Europe, he was widely known as an excellent engraver. His series 'Apocalypse', printed in the printing house of his godfather Anton Koberger, were sold out in huge amounts. In Italy, the cradle of art, Dürer was maliciously copied. The artist was suing the authors of fakes, defending his good name. He painted 'Rosenkranzfest' (Feast of the Rosary or Rose Garlands) to prove the doubters Italians that in painting he was as great as in etching, engraving and woodcut . This new self-portrait sent a message declaring that Dürer was no longer a craftsman (in his native Nuremberg, artists were still regarded as a craft class' representatives) but an artist, and therefore God’s elect.

It was a new self-identification of the Renaissance artist, not of a medieval craftsman. Dürer defiantly painted himself as a gentleman, dressed in light toned clothes and looking his best. He wears an open black and white doublet with a striped cap in the same colours, a white silk undershirt trimmed with gold and a silk cord of blue and white threads holding up a grey-brown cloak that falls over his right shoulder. He has grown a nifty beard, which, it seems, still smells of Venetian perfumes, and his red-gold hair carefully curled. That made pragmatic fellows in his hometown ridicule. In Nuremberg, his wife or mother hid his attire in a dower chest for Albrecht, the craftsman, had no right to allow himself such a defiant luxury.

Dürer has sheathed the hands that he uses to paint in grey kidskin gloves indicative of high rank with the aim of elevating his social status from that of craftsman to artist and of locating painting among the liberal arts, as in Italy. Expensive dress by Venetian fashion and mountain landscape outside the window (a tribute to his mentor Giovanni Bellini) convey the idea that Dürer no longer agreed to consider himself a provincial craftsman, limited by the conventions of time and space.

Self-Portrait in Fur Coat, or Self-Portrait with Fur Collar, or Self-Portrait at the age of Twenty-Eight, or Self-Portrait of 1500 at the Alte Pinakothek.

He consciously compares himself to Christ making his transparent gaze looking into eternity, beautifying all his outlook and composing his hands in a gesture of blessing. Was it an audacity to paint himself in the image of the Savior? Dürer was known as a fervent Christian, for him being like Christ was a mission and a duty of a believer. "Help us to recognize your voice, help us not to be allured by the madness of the world, so that we may never fall away from you, O Lord Jesus Christ." - he wrote.

Some scholars suggest that the year the self-portrait was painted brings the hidden meaning in it. In 1500, as in any 00 year of each century, humanity once again expected the end of the world. So, this self-portrait implies a kind of a spiritual testament by Dürer.

Self-Portrait in the image of the Dead Christ?

Some scholars name Dürer's drawing 'Head of the Dead Christ,' depicting the head of the dead Jesus tilted back, as Albrecht’s self-portrait. And it makes sense. It is known that when he was about the age of the Christ, he fallen sick and was at death’s door. Several days he lay with dry lips and sunken eyes, emaciated by the fewer. At that moment everybody thought he would call the priest. Instead he asked for a mirror, put it on his chest and stared at his reflection for a long time, barely finding strengths to lift his head. This frightened relatives a lot. They might have thought that he’s lost his mind because of the illness for no one has yet occurred on his deathbed to admire himself in a mirror. When he recovered, he made this drawing from memory.

There is an inscription below the drawing, in charcoal "1503", with the artist’s monogram, and along the lower edge, faintly in German: "I produced these two countenances when I was ill." The other 'countenance' to which Dürer refers is probably the 'Head of a Suffering Man', kept also in the British Museum, which is of a comparable size and technique. Both portray suffering, which is a likely subject for Dürer to turn to during his illness.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, Head of the dead Christ, 1503. Drawing in charcoal on paper. The British Museum.

Self-Portraits of Albrecht Dürer known to us from the words only.

Both are telling about Dürer's virtuosity, and therefore their descriptions are noteworthy, although we do not know which self-portraits they mention.

Giorgio Vasari tells about "Albert Dürer, the great German painter and engraver, [who] sent to Raffaella a tribute of his own works, a portrait of himself painted in water-colour on very fine linen, so that it showed equally on both sides. And Raffaella, marveling at it, sent to him many drawing from his own hand, which were much prized by Albert."

The accident with Dürer and his faithful dog, described by Sheurl, repeated a story based on an anecdote of the Roman writer Pliny who reckoned that only dogs know their names and are able to recognize their master even if he appears unexpectedly.

"… Once, when Dürer has just finished his new self-portrait and put it to dry on sun, his dog was running by and licked his image, thinking it run against its master. And I can testify that even today one can see a trace of it. Besides, often the maids were trying to wipe away the cobweb painted by him!"

Cameo appearances (Dürer depicting himself in multi-figure scenes)

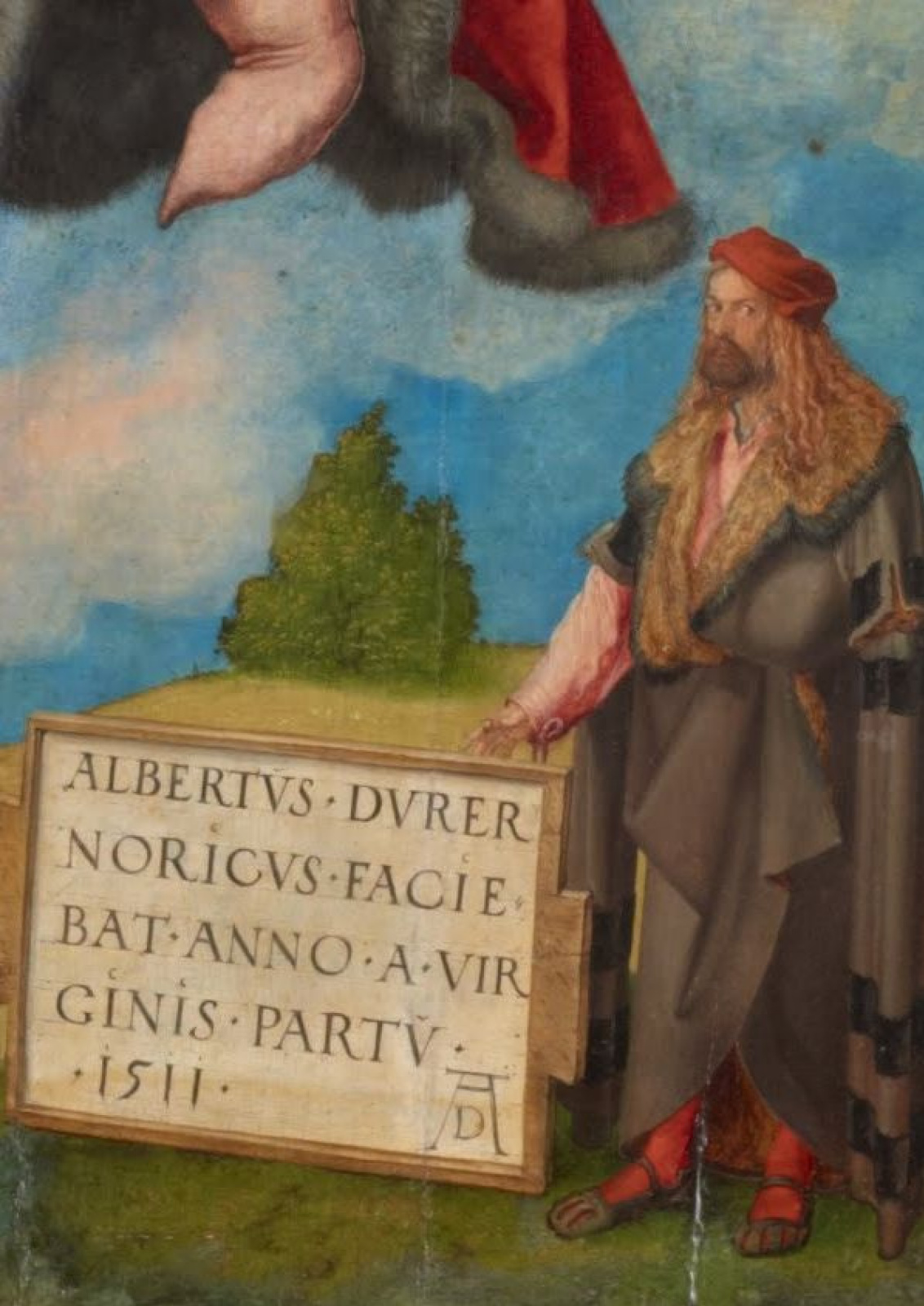

In the right corner of the altar painting 'Rosenkranzfest' (Feast of the Rosary) commissioned by the German community in Venice, Dürer portrays himself in a magnificent attire. In his hands he holds a cartouche with a short inscription reporting that Albrecht Dürer completed the painting in five months, but actually work lasted at least eight. It was important for Dürer to prove to the doubting Italians that in painting he was as good as in engraving.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, detail of 'Rosenkranzfest' (Feast of the Rosary), 1506.

The Jabach Altarpiece also known as the Job’s Altar was probably commissioned by Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, for a chapel in his castle at Wittenberg, in occasion of the end of the plague in 1503. The altarpiece was later acquired by the Jabach family, who kept it at their family chapel in Cologne until the end of the eighteenth century. The wings were then sawn apart and separated, the central panel was lost.

The exteriors show the story of Job: the left one depicts the long-suffering Job and his wife, and on the right one, musicians came to comfort Job. The drummer on the right is a self-portrait of Dürer. In reality, the artist was interested in music, he tried to play the lute. But there is more of Dürer in this image, it’s his inherent extravagance in the choice of clothes. Dürer, the drummer, portrays himself in a black turban and a short orange cape, unusual in cut.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, right wing of the Jabach Altarpiece, Piper and Drummer, c. 1503 — 1504. Collection of Ferdinand Franz Wallraf.

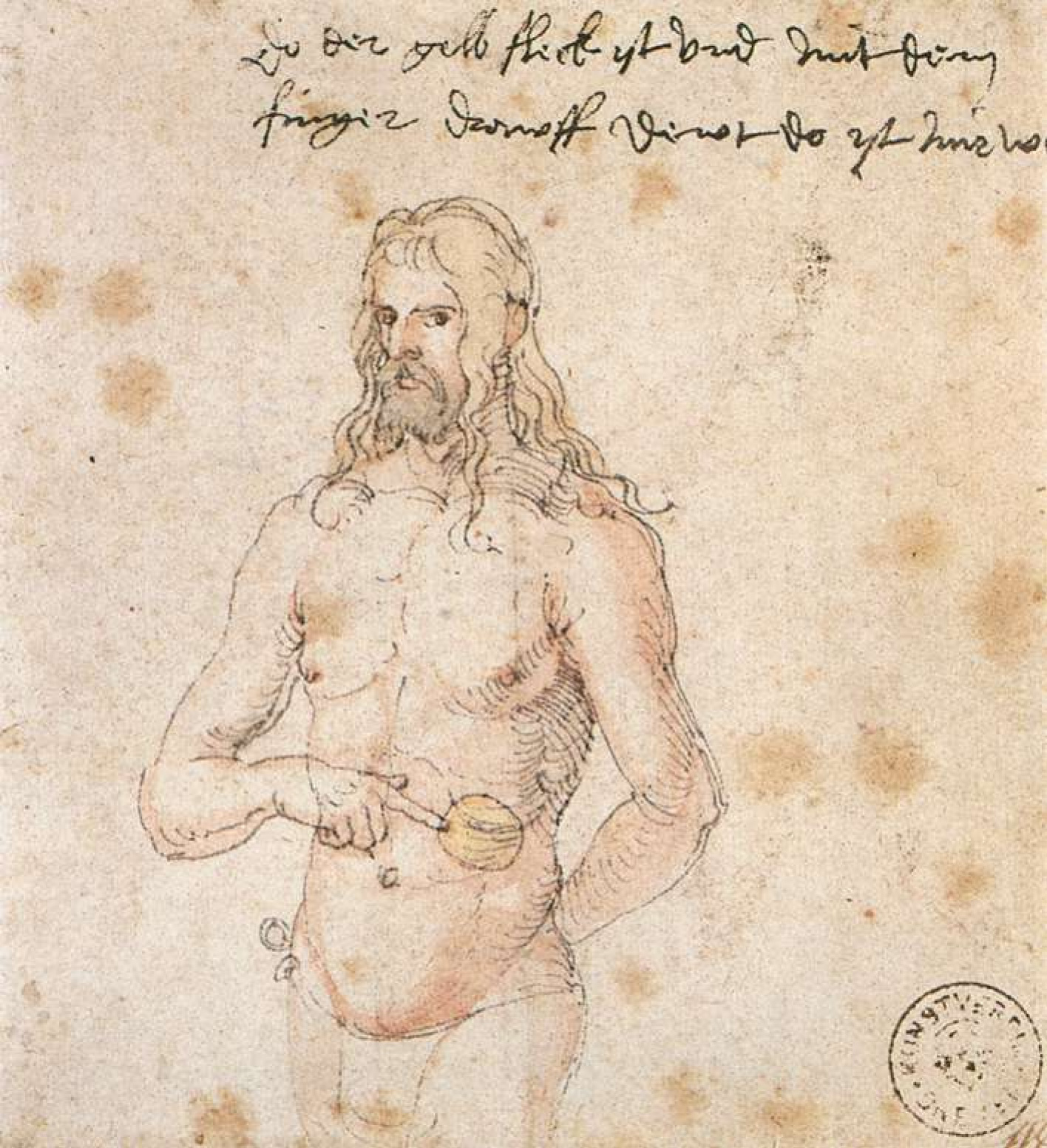

Naked Dürer

The Dürer's frank manner of depicting nude male figure, not just someone but himself, was unprecedented and shocking up to the twentieth century when similar experiments were made by Lucian Freud (1922−2011). In many editions this three-quarter length self-portrait of Dürer shamefacedly cut off at waist level.

However, one needs to understand that Dürer had no wish to shock anybody. Rather, he was moved by the same interest of the Renaissance scientist, who at 13 years of age made the future artist to get interested in his own face, and to immediately check whether he would "double the nature" by depicting what he saw, in drawing. Moreover, in Germany at Dürer's times, depicting nude body image from nature was a serious problem: in contrast to Italy, where it was easy to find sitters of both sexes and it costed not too much, in Germany it was not accepted to pose naked for artists. Dürer complained a lot that he had to learn to draw the human body on the works of Italians (Andrea Mantegna and others). Giorgio Vasari in his 'Lives of Marc' Antonio Bolognese (Raymondi) (1480−1527/34)' even makes a condescending pungent passage about Dürer's skills to portray naked body:

"I am willing, indeed, to believe that Albrecht was perhaps not able to do better because, not having any better models, he drew, when he had to make nudes, from one or other of his assistants, who must have had bad figures, as Germans generally have when naked, although one sees many from those parts who are fine men when in their clothes."

Even if indignantly reject the Vasari’s attack about the ugliness of the German bodies, it is quite naturally to assume that having the perfect body proportions himself, Dürer has used his own figure in his artistic and anthropometric studies. In time, questions of human body structure and the relation of its parts, became the crucial in Dürer's work.

In his woodcut The Men’s Bath, Dürer has found a legal and successful opportunity to depict nude male figures, in no way insulting public morality and foreseeing the accusations from conservatives and prudes. Bathhouses were a special pride of German cities. Like the Roman baths, they serve as a communal meeting place for both washing, friendly get-togethers and substantive discussions. Naturally, men do not wear clothes in a bathhouse!

However, the print is not simply a study of the male figure. The man standing against the water pipe is the artist himself, while the plump seated man drinking from a tankard is clearly a portrait of Dürer's friend, Willibald Pirckheimer. The two figures in the foreground have been tentatively identified as Lukas and Stephan Paumgartner, friends of Dürer. If the observer in the background is included, the figures stand for the five senses: Dürer as hearing, Pirckheimer as taste, the figure holding the flower as smell, his companion as touch and the onlooker in the background as sight.

Left: Albrecht Dürer, The Men’s Bath, 1496/97.

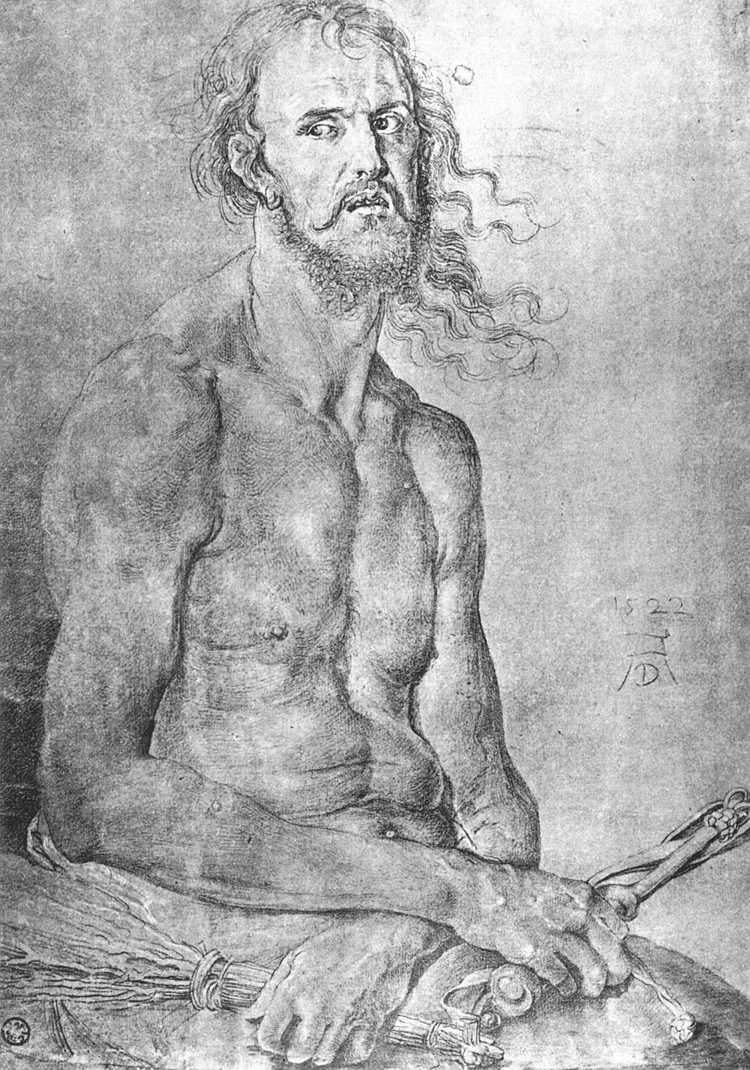

Dürer's Self-Portraits as the Man of Sorrows.

This self-portrait of the late period paradoxically combines two guidelines from the earlier work: he uses his naked body as nature and identifies himself with Christ in a certain way. By drawing his body, no longer young, and his face, touched by the aging, he traces how his muscles and skin gradually become flabby, forming skin folds which he hasn’t have even yesterday. Dürer captures changes with sober objectivity. At the same time, he creates his self-portrait in accordance with the "Man of Sorrows" iconographic type.

The Man of Sorrows is taken to be the figure of Christ, clearly marked by the wounds of the Passion, subsequent to the events of his Crucifixion and Death on the Cross. The name by which the Western image is commonly known comes from the Old Testament book of Isaiah. The image represents tormented Christ in a crown of thorns, half-naked, beaten, spat upon, with a bloody wound under his ribs (1, 2).

Poverty, disease, litigation with customers and arrest of favorite students, accused of impiety, the refusal of Nuremberg’s authorities to pay the artist his annual allowances, set by the late Emperor Maximilian, a lack of understanding in his family filled Dürer's last few years. They were not easy but full of sadness. A malarial infection, contracted in 1521 when the 50-year-old artist went to Zeeland in the hopes of seeing a stranded whale, periodically recurred until his death. Severe illness (possibly pancreatic tumor) resulted in a weight loss. According to Willibald Pirckheimer, Durer has dried, "like a bundle of straw."

And when he was buried without special honors, for the Nuremberg craftsman had no rights for them, unreasonable admirers of his genius insisted on exhumation to make his death mask. They cut off his famous wavy curls and take them to pieces. As if the memory of him needed these props of his mortal flesh… Dürer has left immortal evidences of himself — his prints, paintings, books, and finally, self-portraits.