Stories of professional jealousy, mutual aversion, insurmountable disagreements, and sometimes even irreconcilable hostility between the artists in the series of Arthive.

It is believed that Marc Chagall and Kazimir Malevich were enemies. Malevich really proved disastrous for Chagall — at least, it could seem so in 1919, the year of their acquaintance.

Malevich took over Chagall’s students. In fact, he drove Chagall out from the People’s Art School (founded by the artist) and his native city of Vitebsk.

However, this conflict wasn’t face-to-face. During the legendary "war", these two hardly exchanged a hundred words, they barely even knew each other. Malevich wasn’t at feud with Chagall and definitely never meant to hurt him. Kazimir became a tool or, if you like, a toy in the hands of the universe, which was so eager to understand, explain and harness. And which, as you know, has a certain type of irreverent humour.

Malevich took over Chagall’s students. In fact, he drove Chagall out from the People’s Art School (founded by the artist) and his native city of Vitebsk.

However, this conflict wasn’t face-to-face. During the legendary "war", these two hardly exchanged a hundred words, they barely even knew each other. Malevich wasn’t at feud with Chagall and definitely never meant to hurt him. Kazimir became a tool or, if you like, a toy in the hands of the universe, which was so eager to understand, explain and harness. And which, as you know, has a certain type of irreverent humour.

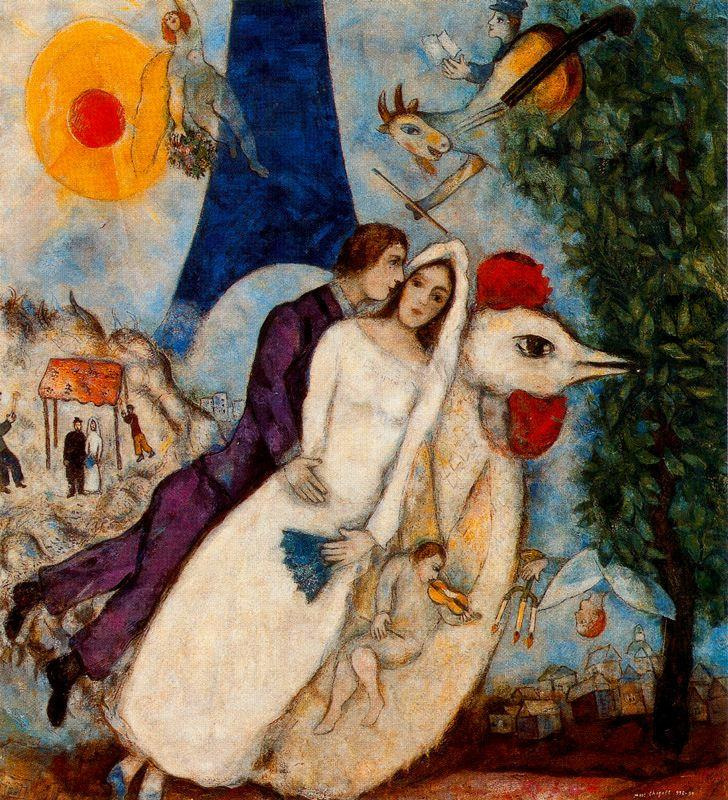

The betrothed and Eiffel tower

1913, 77×70 cm

Tomorrow was the War

In 1914, Marc Chagall came from Paris to his native Vitebsk to finally get married. His bride, Bella Rosenfeld, had been patiently waiting for him for four years. The couple planned to move to Europe after their wedding. But the war began. Chagall found himself unable to leave for Paris. In his memoirs, the artist wrote: "My documents were confiscated and sealed. I feel like I’ve been stripped naked, and I’ve grown a beard and hair." Chagall just accepted it. Taking his clothes off was a common thing for him — while living in Paris, he made it a habit to paint naked. He sincerely loved his small homeland and even called Paris the "second Vitebsk". He wanted to establish an art school there, and this idea carried him through his most difficult years.

In 1917, 30-year-old Chagall was appointed Fine Arts Commissioner of the Province of Vitebsk. He gained some standing in Moscow and abroad, and his works seemed to the new government revolutionary enough to pass for "proletarian art". Two years later, Chagall founded and headed the People’s Art School in Vitebsk — the work of his life, as he then thought.

Those were troubled times. Somewhere nearby there was a civil war.

In November 1919, Kazimir Malevich entered the city.

Red cavalry gallops

1932, 140×91 cm

World Champion

Using Malevich’s own terminology, we can say that he came to Vitebsk due to "food considerations". Initiatives related to education and art were quite generously funded by the government there, and in general, provinces were richer than capitals. Among other things, Malevich was attracted by the opportunity to publish his work On New Systems in Art in Vitebsk — which he didn’t manage to do in Moscow.

When the teacher at the People’s Art School El Lissitzky (who back in 1918 was still known as Lazar) offered him to move to Vitebsk, Kazimir Malevich quickly packed up his suitcases.

However, his arrival was arranged in such a way that no one would dare to suspect Malevich that he appeared in Vitebsk for the sake of bread, firewood or living space.

This is how the art historian Alexandra Shatskikh described his arrival: "The whole school gathered downstairs, in the hall of the building, where general meetings always took place. There was an open single-flight staircase leading from the hall to the second floor of the building. M. Chagall announced the arrival of a new teacher at the school — and after this speech a round-headed strong man appeared upstairs and slowly began to go down, making wide sweeping movements with his hands. Downstairs, he went to the podium and, without saying a word, continued to do something resembling gymnastic exercises; his massive, stocky built made him look like a wrestler or an athlete. The effect was stunning."

No, it wasn’t a new teacher who came to lead the local workshop — it was a Superstar, Space Messiah, and "World Champion", as Malevich described himself in a letter to the historian of culture Mikhail Gershenzon.

At first, Chagall didn’t realize what was happening. And it was not the right time to be picky about staff members. "Everyone who expressed the desire to work for me, immediately became a teacher, because I considered it useful that the school had a variety of artistic directions," he recalled in his memoirs.

Using Malevich’s own terminology, we can say that he came to Vitebsk due to "food considerations". Initiatives related to education and art were quite generously funded by the government there, and in general, provinces were richer than capitals. Among other things, Malevich was attracted by the opportunity to publish his work On New Systems in Art in Vitebsk — which he didn’t manage to do in Moscow.

When the teacher at the People’s Art School El Lissitzky (who back in 1918 was still known as Lazar) offered him to move to Vitebsk, Kazimir Malevich quickly packed up his suitcases.

However, his arrival was arranged in such a way that no one would dare to suspect Malevich that he appeared in Vitebsk for the sake of bread, firewood or living space.

This is how the art historian Alexandra Shatskikh described his arrival: "The whole school gathered downstairs, in the hall of the building, where general meetings always took place. There was an open single-flight staircase leading from the hall to the second floor of the building. M. Chagall announced the arrival of a new teacher at the school — and after this speech a round-headed strong man appeared upstairs and slowly began to go down, making wide sweeping movements with his hands. Downstairs, he went to the podium and, without saying a word, continued to do something resembling gymnastic exercises; his massive, stocky built made him look like a wrestler or an athlete. The effect was stunning."

No, it wasn’t a new teacher who came to lead the local workshop — it was a Superstar, Space Messiah, and "World Champion", as Malevich described himself in a letter to the historian of culture Mikhail Gershenzon.

At first, Chagall didn’t realize what was happening. And it was not the right time to be picky about staff members. "Everyone who expressed the desire to work for me, immediately became a teacher, because I considered it useful that the school had a variety of artistic directions," he recalled in his memoirs.

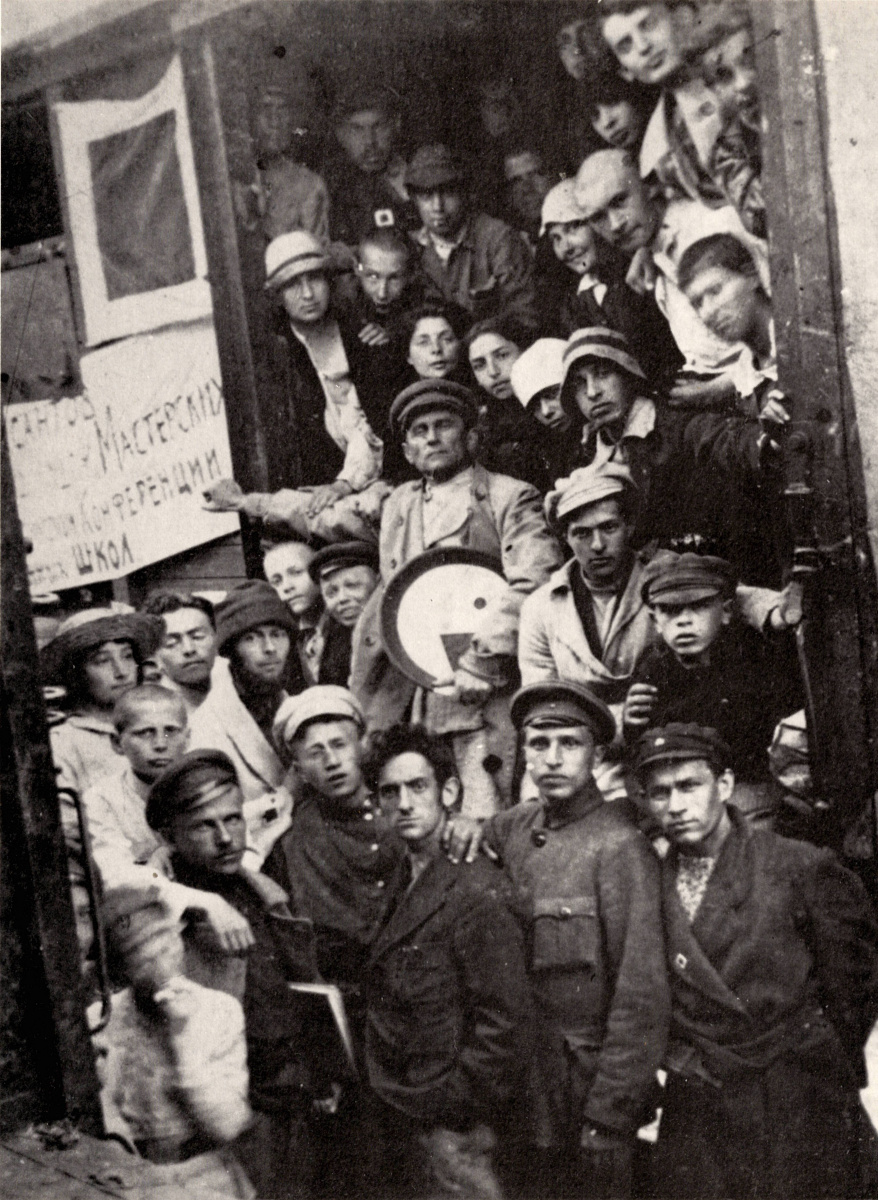

Affirmers of New Art. Vitebsk, 1922. Malevich is the second from left in the top row.

Soon, Malevich organized students into a group under the name of UNOVIS (the abbreviation meaning Affirmers of New Art), the branches of which rapidly spread around the country (already in 1920, they were opened in Moscow, Smolensk, Saratov and Perm). The members of the UNOVIS group greeted each other with a "suprematist" exclamation "u-el-el-u-el-te-ka!", spoke mainly in interjections and abbreviations, published almanacs, manifestos and "affirmations". All this was something between a sect and a party.

It took Malevich about six months to take over everything that Chagall lived for in Vitebsk. In May 1920, almost every student of "individualistic" workshops joined UNOVIS as the "only group leading to creative work". In Vitebst, UNOVIS monopolized everything that was somehow connected with artistic activity. In their Suprematist manner, the members of UNOVIS decorated trams, developed designs for ration cards, the interiors of state institutions and city facades. Chagall was left alone, the work of his life fell under the weight of Malevich’s lead charisma.

A born leader, Malevich knew how to charm and intrigue an intellectual like Gershenzon, a famous writer. Needless to say how much he could influence the impressionable commoner: for his students, Malevich was not a mentor, but a deity. Among other things, he proved to be an effective manager at the School. While Chagall tried to teach his students to draw, Malevich "taught them Suprematism." After a couple of months of his classes (mostly theoretical ones), the student was considered a ready-made artist. Of course, Chagall had no chance.

All this high drama took place against the backdrop of quite domestic squabbles. Malevich occupied the accommodation which Chagall claimed to possess (in all fairness, it bears mentioning that Malevich most likely didn’t know about that). Chagall’s salary as the head of the People’s Art School was 4800 rubles. For comparison, some time after his departure from Vitebsk, Malevich was assigned a personal salary of 120 thousand rubles. Chagall felt not only lonely and betrayed, but also humiliated.

It took Malevich about six months to take over everything that Chagall lived for in Vitebsk. In May 1920, almost every student of "individualistic" workshops joined UNOVIS as the "only group leading to creative work". In Vitebst, UNOVIS monopolized everything that was somehow connected with artistic activity. In their Suprematist manner, the members of UNOVIS decorated trams, developed designs for ration cards, the interiors of state institutions and city facades. Chagall was left alone, the work of his life fell under the weight of Malevich’s lead charisma.

A born leader, Malevich knew how to charm and intrigue an intellectual like Gershenzon, a famous writer. Needless to say how much he could influence the impressionable commoner: for his students, Malevich was not a mentor, but a deity. Among other things, he proved to be an effective manager at the School. While Chagall tried to teach his students to draw, Malevich "taught them Suprematism." After a couple of months of his classes (mostly theoretical ones), the student was considered a ready-made artist. Of course, Chagall had no chance.

All this high drama took place against the backdrop of quite domestic squabbles. Malevich occupied the accommodation which Chagall claimed to possess (in all fairness, it bears mentioning that Malevich most likely didn’t know about that). Chagall’s salary as the head of the People’s Art School was 4800 rubles. For comparison, some time after his departure from Vitebsk, Malevich was assigned a personal salary of 120 thousand rubles. Chagall felt not only lonely and betrayed, but also humiliated.

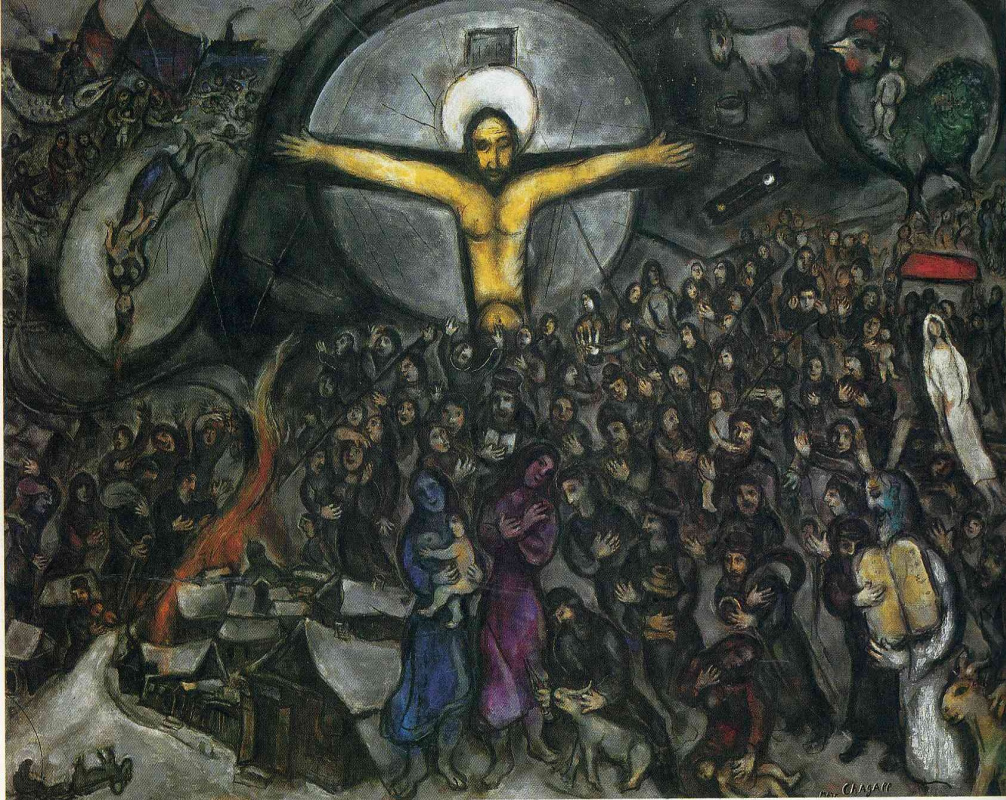

Revolution

1937, 50×100 cm

Greetings to Lunacharsky!

If you don’t know the details, it may seem that this whole story reminds of Bulgakov’s plots. A famous artist, a master and an enthusiast wants to work in piece — to teach students during the day (in the workshops of his school), and to have dinner in the evening (preferably in his dining room). And then there was Malevich with his UNOVIS group: leather jackets, shoulder belts, brochures, Newspeak, and reallocation of living space. Just like the meeting of Professor Preobrazhensky with Shvonder. In fact, the situation was somewhat different.

Chagall didn’t have a shoulder belt. But his personal bodyguard did. The fact that Chagall walked around his native Vitebsk with security doesn’t really fit with the image of the vulnerable artist. Unlike Professor Preobrazhensky, Chagall not only had patrons among the authorities — he was an authority himself. And like any power, he didn’t feel welcomed. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Chagall was local. In Vitebsk, everyone knew and remembered his father, who worked as a clerk in a grocery store and always smelled like herring brine. Chagall with his personal security and the mandate, issued allegedly by Lunacharsky himself, was considered an upstart. He made it easy for Malevich to seem a big metropolitan celebrity in Vitebsk.

In general, Malevich was far from the only reason that Marc Chagall left or, if you wish, fled from Vitebsk. Everything he did there after returning from Paris turned into failure.

If you don’t know the details, it may seem that this whole story reminds of Bulgakov’s plots. A famous artist, a master and an enthusiast wants to work in piece — to teach students during the day (in the workshops of his school), and to have dinner in the evening (preferably in his dining room). And then there was Malevich with his UNOVIS group: leather jackets, shoulder belts, brochures, Newspeak, and reallocation of living space. Just like the meeting of Professor Preobrazhensky with Shvonder. In fact, the situation was somewhat different.

Chagall didn’t have a shoulder belt. But his personal bodyguard did. The fact that Chagall walked around his native Vitebsk with security doesn’t really fit with the image of the vulnerable artist. Unlike Professor Preobrazhensky, Chagall not only had patrons among the authorities — he was an authority himself. And like any power, he didn’t feel welcomed. The situation was aggravated by the fact that Chagall was local. In Vitebsk, everyone knew and remembered his father, who worked as a clerk in a grocery store and always smelled like herring brine. Chagall with his personal security and the mandate, issued allegedly by Lunacharsky himself, was considered an upstart. He made it easy for Malevich to seem a big metropolitan celebrity in Vitebsk.

In general, Malevich was far from the only reason that Marc Chagall left or, if you wish, fled from Vitebsk. Everything he did there after returning from Paris turned into failure.

The outcome

1966, 130×162 cm

The most resounding of them was, perhaps, decorating the city on the occasion of the first anniversary of the October Revolution. It was a huge event. Seven triumphal arches were built on the squares of the city. The artist and his apprentices (in the interests of the revolution, all those who could hold a brush or roller in their hands and were able to draw at least letters from sketches were recruited into Chagall’s assistants) created many panels and large-scale posters. According to eyewitnesses, there were at least five hundred of them. However, the citizens didn’t appreciate that tremendous effort. In the context of revolutionary agitation, his images produced a powerful psychedelic effect. Green horses. Levitating Jews. Self-portrait with his wife floating in the air, entitled as Greetings to Lunacharsky!

In his book, My Life, Chagall wrote: "The workers marched up singing The Internationale. When I saw them smile, I was sure they understood me. The leaders, the Communists, seemed less gratified. Why is the cow green and why is the horse flying through the sky, why? What’s the connection with Marx and Lenin?"

For some time, the artist cherished the hope that at least the "people" were on his side. But they weren’t: the proletarians laughed at his green horses much louder than the more or less educated "commissars".

In his book, My Life, Chagall wrote: "The workers marched up singing The Internationale. When I saw them smile, I was sure they understood me. The leaders, the Communists, seemed less gratified. Why is the cow green and why is the horse flying through the sky, why? What’s the connection with Marx and Lenin?"

For some time, the artist cherished the hope that at least the "people" were on his side. But they weren’t: the proletarians laughed at his green horses much louder than the more or less educated "commissars".

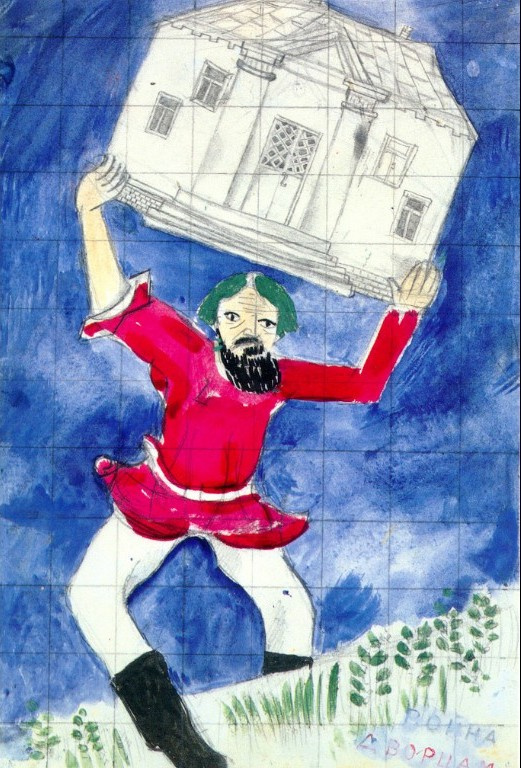

War to the palaces

1918

Chagall’s cooperation (as that of a representative of the authorities) with local artists, artisans, painters and the like was voluntary-compulsory. Chagall created at the School something like an guild, distributing orders — this, of course, also did not add to the number of his friends in the city.

However, Malevich’s part in it should not be underestimated. Chagall put up with ridicule, envy and domestic hardships as long as he had his job. The loss of students who collectively jumped over under the Suprematist banners of Kazimir Malevich made his life in Vitebsk not only difficult, but also meaningless.

However, Malevich’s part in it should not be underestimated. Chagall put up with ridicule, envy and domestic hardships as long as he had his job. The loss of students who collectively jumped over under the Suprematist banners of Kazimir Malevich made his life in Vitebsk not only difficult, but also meaningless.

Kazimir Malevich and UNOVIS. Vitebsk. 1920.

The winner gets nothing

In June 1920, Malevich and his flock went to the exhibition in Moscow. There’s a picture taken on the day of their departure at the Vitebsk railway station: the members of UNOVIS hang from the crowded carriage, their shepherd is in the center, and a Suprematist icon — a black square — is pinned against the heat pipe.

Biographers believe that Marc Chagall was on the same train, leaving Vitebsk forever. A paradoxical irony: Malevich and Chagall were on the same train, but moved in opposite directions. The first one rushed towards a triumph, even though it turned to be a short one. The second one — betrayed, humiliated and frustrated — went into exile.

Two years later, Chagall would leave for Germany, and later — to Paris. He received French citizenship. Got married twice. Was awarded the Erasmus Prize and the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour. The French government commissioned him the painting of the 20-meter ceiling of the Opéra Garnier in Paris. Moreover, he became the first living artist to be exhibited at the Louvre. Marc Chagall lived to be 97 years old.

In June 1920, Malevich and his flock went to the exhibition in Moscow. There’s a picture taken on the day of their departure at the Vitebsk railway station: the members of UNOVIS hang from the crowded carriage, their shepherd is in the center, and a Suprematist icon — a black square — is pinned against the heat pipe.

Biographers believe that Marc Chagall was on the same train, leaving Vitebsk forever. A paradoxical irony: Malevich and Chagall were on the same train, but moved in opposite directions. The first one rushed towards a triumph, even though it turned to be a short one. The second one — betrayed, humiliated and frustrated — went into exile.

Two years later, Chagall would leave for Germany, and later — to Paris. He received French citizenship. Got married twice. Was awarded the Erasmus Prize and the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour. The French government commissioned him the painting of the 20-meter ceiling of the Opéra Garnier in Paris. Moreover, he became the first living artist to be exhibited at the Louvre. Marc Chagall lived to be 97 years old.

Malevich’s path would be marked by completely different milestones: espionage charges, prison, poverty, disgrace, cancer, death at 56.

In Chagall’s life, Malevich (how can we not recall Bulgakov again?) played the role of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good. Except that he never wished Chagall evil. Kazimir Malevich was the element, the embodied idea of the revolution, he did not care whom or what to subvert. Repin. Serov. Chagall. Painting in general.

In 1973, Marc Chagall — already worldwide famous — visited the USSR. But he didn’t come to Vitebsk. Maybe he was too scared to see that his native city became unrecognizable. Or just on the contrary: the artist could fear that he would be flooded with too painful memories. He painted that city until his death; Vitebsk motifs can be found even on the ceiling of the Opéra Garnier. However, he hardly considered Malevich, who made him flee from Vitebsk, his enemy. In his book My Life, he recalled many old grudges. And yet, there was only one, completely neutral sentence about Malevich.

That was their bewildering war: without hatred, battle action, and a winner. The war which was bewildering because it didn’t really happen.

In Chagall’s life, Malevich (how can we not recall Bulgakov again?) played the role of that power which eternally wills evil and eternally works good. Except that he never wished Chagall evil. Kazimir Malevich was the element, the embodied idea of the revolution, he did not care whom or what to subvert. Repin. Serov. Chagall. Painting in general.

In 1973, Marc Chagall — already worldwide famous — visited the USSR. But he didn’t come to Vitebsk. Maybe he was too scared to see that his native city became unrecognizable. Or just on the contrary: the artist could fear that he would be flooded with too painful memories. He painted that city until his death; Vitebsk motifs can be found even on the ceiling of the Opéra Garnier. However, he hardly considered Malevich, who made him flee from Vitebsk, his enemy. In his book My Life, he recalled many old grudges. And yet, there was only one, completely neutral sentence about Malevich.

That was their bewildering war: without hatred, battle action, and a winner. The war which was bewildering because it didn’t really happen.

The gray house. Vitebsk

1917, 68×74 cm

Author: Andrii Zymohliadov

Cover illustration: On the left — Marc Chagall. Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers. 1913. On the right — Kazimir Malevich. Self-Portrait. 1910.

Cover illustration: On the left — Marc Chagall. Self-Portrait with Seven Fingers. 1913. On the right — Kazimir Malevich. Self-Portrait. 1910.