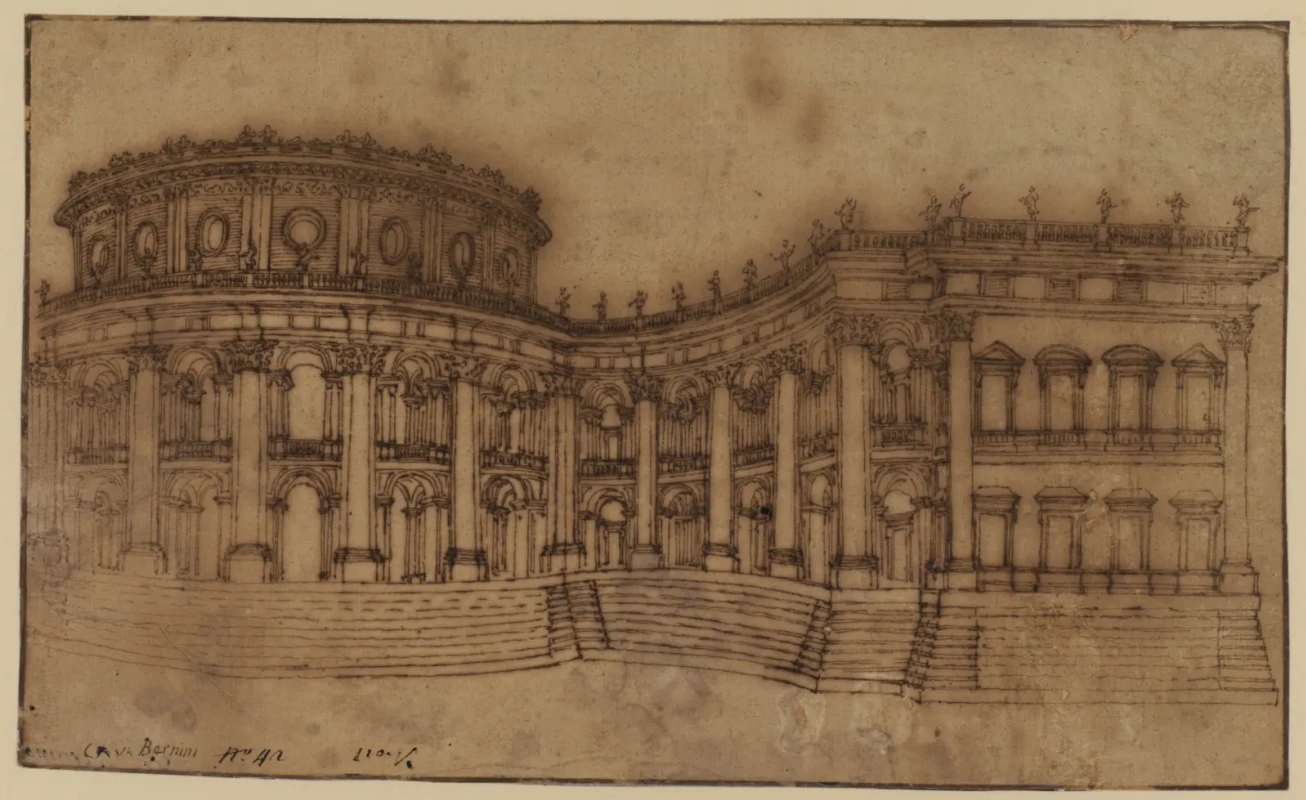

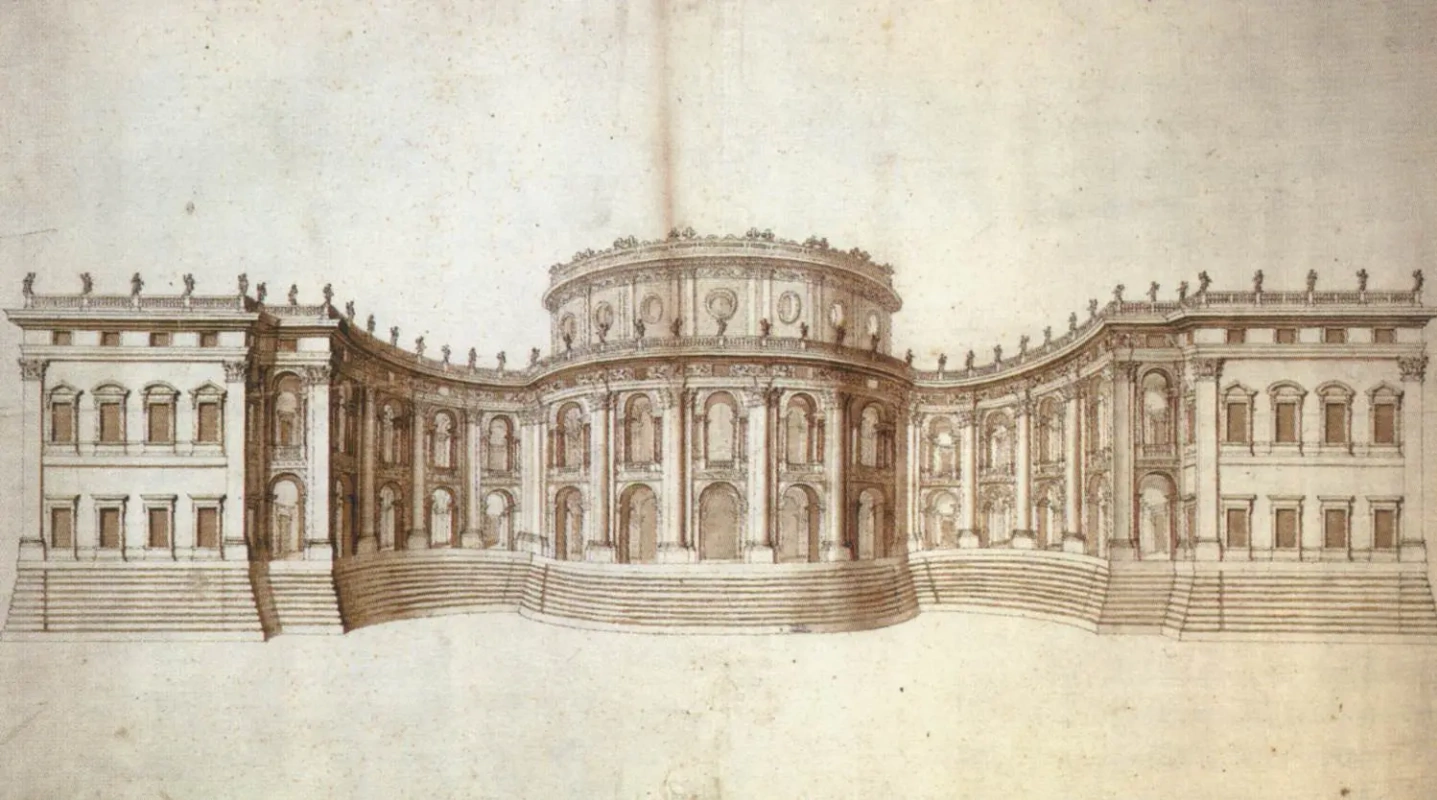

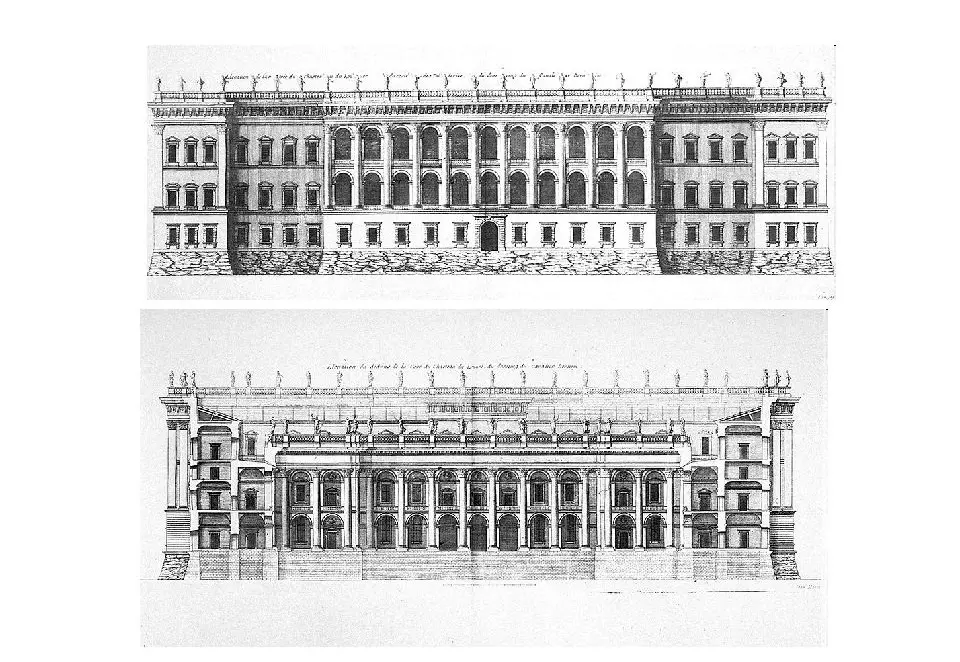

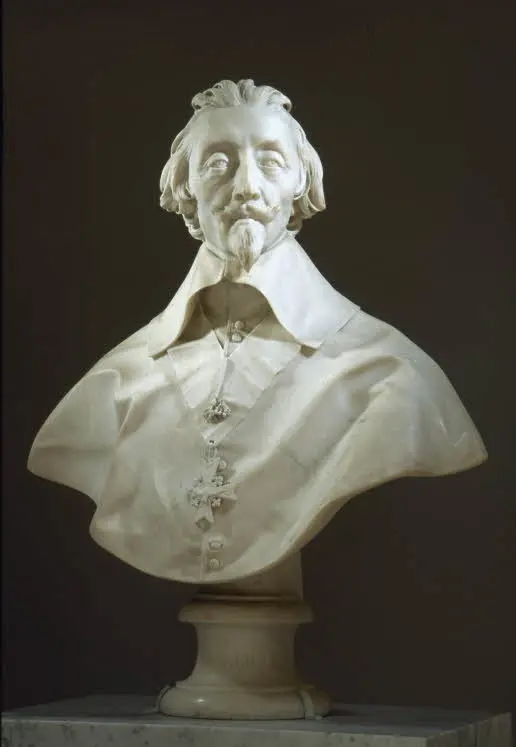

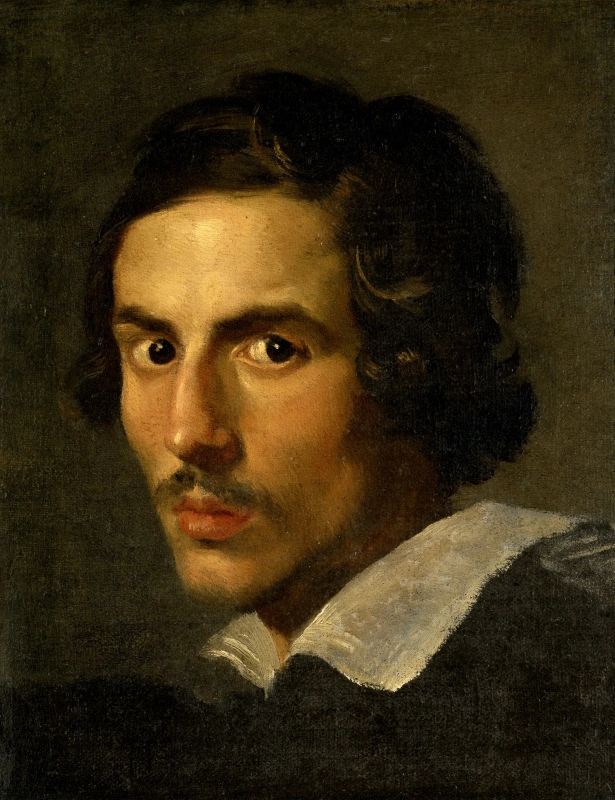

Bernini’s projects for the Louvre never materialized due to the antagonism between the Italian artist and some French courtiers. However, the portrait bust, which was the result of a more personal relationship between the king and the sculptor, was completed and called "the greatest portrait of the Baroque era".

This determined the nature of Bernini’s entire life — to work for successive popes, to endure his comparison with Michelangelo and receive money. He died at 82 in wealth and honour.

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini. The Rape of Proserpina (detail). Borghese Gallery, Rome

The dynamic new concept that he introduced in this scene defined the sculptural canons for the next 150 years. Connoisseurs noted the realistic effects that the artist achieved on solid marble — the texture of the skin, the strands of hair, the tears of Proserpina and most of all, the pliant body of the girl.

"I subdued marble, I made it plastic like wax.." Bernini wrote. And his son and biographer Domenico called the scene "an amazing contrast of tenderness and cruelty".

However, in the 18th and 19th centuries, critics looked for errors in the statue and found them. The Frenchman Jérôme de Lalande allegedly wrote: "Pluto’s back is broken; his figure is extravagant, characterless, it lacks nobility of its expression and features poor outlines; the woman is no better." Another of his compatriots, who visited Villa Ludovisi, where the work was located, said: "Pluto's head is vulgarly pederastic; his crown and beard make him funny, the muscles and posture are emphatically expressive. This is not a true divinity, but a decorative god…"

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini. Bust of Thomas Baker (1638). Victoria and Albert Museum, London

For example, consider the bust of the elegant British courtier Thomas Baker (it is in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London now). This nobleman was sent to Rome with the triple portrait of Charles I by Anthony van Dyck. The artist depicted the king from three points of view, so that Bernini, who had never met the ruler, created his bust that would embody the dignity of the absolute monarchy and the Catholic faith as its consequence (before his death, Charles II converted to Catholicism).

In the Eternal City, Baker commissioned Bernini his own image in marble as well. The result is a playful, friendly portrait of the foppish gentleman. Most likely, an apprentice sculptor completed it. However, the statue is, in fact, a work by Bernini — due to the masterly work on marble. The royal bust was destroyed in a fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698.

This may explain the sudden disturbing intimacy of Bernini’s most famous sculpture, The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. The composition is the focal point of the artist-designed Cornaro Chapel in the Roman church of Santa Maria della Vittoria. The viewer feels as if in a theatrical space: in the centre of the "stage" are the main characters — the saint and the angel, who are watched as if from boxes from the right and left by the members of the Cornaro family, imprinted in marble.

When Salvador Dalí, in his surreal collage , The Phenomenon of Ecstasy, pointed out the similarity of Catholic images of holy ecstasy with orgasm, he deliberately did it blasphemously. 300 years ago, Bernini was absolutely orthodox. His sculpture is an accurate visualization of the vision of a Spanish saint. In her autobiography, she describes a little angel with a golden spear "to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God".

During the Renaissance , fountains were the luxury of private princely gardens. Bernini created such a masterpiece in his early period — Neptune and Triton (c. 1620/1), which adorned the pond in the Roman villa of Montalto until 1786. The sculpture was later bought by an Englishman, and now it is exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Bernini democratized fountains. He invented a new kind of visually compact impressive source to bring city squares to life. His Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (Fountain of the Four Rivers) in Piazza Navona is an allegory of papal power, four rivers, four quadrants of the globe, faithful to the Pope. And at the same time, it is a gift to people, pouring fresh cool water all year round over a fantastically skilfully cut stone crowned with an Egyptian obelisk. Bernini said that he loved water, that he was happy watching it flow. He turned it into symbolic blood running through the veins of Rome.

Bernini was a revolutionary, an artist close to us. He abandoned the Renaissance idea that the various arts were rivals — he considered them as an ensemble instead. He practised his own version of installation art in the 17th century. His most striking theatrical performances were performed in the amazing interiors of St. Peter’s — only there he could design large enough decorations that looked harmonious under Michelangelo’s amazing dome.

Bernini was the man whose unconscious has accumulated and poured out in cascades of stone and water all over Rome, who was able to combine his own fantasies with public space. This is why his art is still so exciting, amazing and delightful. Bernini left us a self-portrait in the form of a fairytale city.

Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini. Saint Sebastian (1617). Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

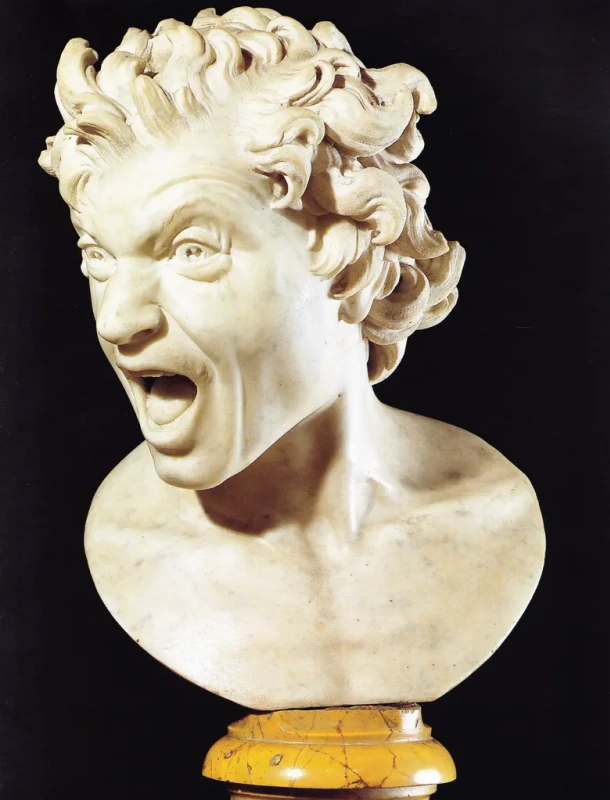

In the autumn of 2019, the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna decided to conduct a dialogue between the works of Bernini and another great artist who lived in Rome, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. The curators wanted to showcase how strong emotions such as fear, horror, surprise, and passion have suddenly become a theme in painting and sculpture. 70 exhibits from the leading public and private collections demonstrated how body movements were determined by the inner impulses and feelings of the subjects.

One of the central pieces at the exhibition was the Saint Sebastian, an early sculpture by Bernini. The unstable, fragile balance of the pose of the hero shot by Roman soldiers reflects the transition between life and death that he experiences. His upward, calm face with parted lips and closed eyes, as well as finely carved marble veins and partly tense body muscles are a prime example of the deep connections between emotional and physical movement that Bernini was researching.