Artist Pauline Boty was the only woman in pop art in the UK. She painted complex collages, as if combined of magazine clippings, portraits of movie stars, fashion writers and political scandal figures; she danced in the evenings, starred in films and interviewed The Beatles. She became a symbol of the era, she died young, and her name disappeared from the lists of important artists and gallery catalogues for 30 years. Now, pop art stories cannot practically do without Pauline Boty.

The Wimbledon College of Art cafeteria in the mid-1950s had far more male students than female ones. At one of the tables, one hears a lively debate about the most important artist of the 20th century. The ardent young man loudly assures that, it is certainly Picasso. A hot 17-year-old blonde, dubbed the Wimbledon Bardot on campus, chuckles: "I'd prefer Paolozzi". The young man gets furious. He is sure that now he will put this probably dim-witted beauty where she belongs: "Why do you need so much red lipstick?" She jumps up to the frightened young man and shouts: "This is to kiss you better!" And then she chases him across the cafeteria and a little more down the corridor. The man turns out to be agile and escapes from this psycho and her kisses. The blonde’s name is Pauline Boty, and they will add "the first woman in pop art in Great Britain" to her name very soon.

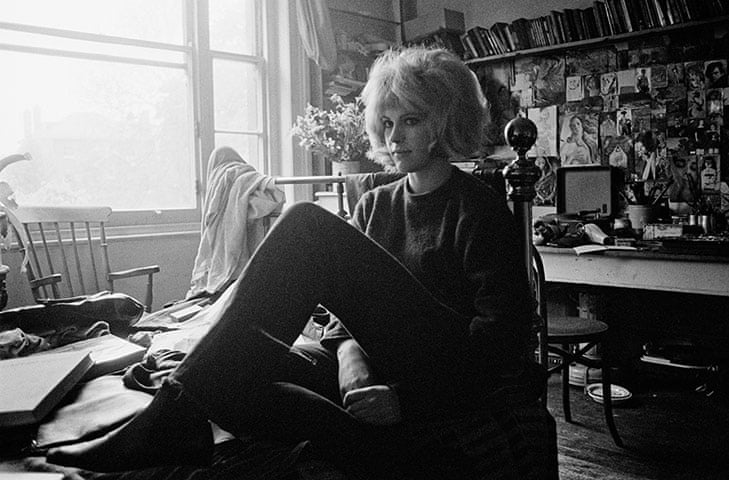

Pauline Boty in her workshop, 1963. Photo: Lewis Morley. Source: www.npg.org.uk

Just a girl

Pauline grew up in the suburbs of London with her three older brothers. Her father, Albert Boty, half Persian, half Belgian, devoted his whole life to becoming an "ordinary Englishman": a devout Catholic, admirer of traditions and rules, croquet and tea, a zealous gardener who planted the most ordinary English roses in the most ordinary English garden. His wife Veronica was a housewife, of course. He himself was an accountant, of course.From their childhood, Albert’s sons figured out the family hierarchy, which (why not?) they confidently projected onto their little world. The younger sister is just a girl. The brothers didn’t hesitate to beat Pauline, they scoffed and beknaved her, and delightedly drove her to rage and screams. When the mother of the family fell seriously ill, the threat loomed over young Pauline, to take her place in the kitchen, in the garden, behind endless laundry and irons gradually and forever. Of course, she wanted to leave her usual English home quickly — and did it as soon as she turned 16. While in other matters her mother Veronica Boty remained silent and submissive, in this venture she suddenly sided with her. Once she stood in the same way in the middle of her own parents' dining room and held a letter with an invitation to an art college in her trembling hands, but she heard her father’s "No!" just like did Pauline now.

Veronica insisted that her daughter got permission to study at Wimbledon College of Art. The father gave up: after all, what’s the difference what nonsense the girl does while waiting for a decent marriage offer, for her own ideal English home.

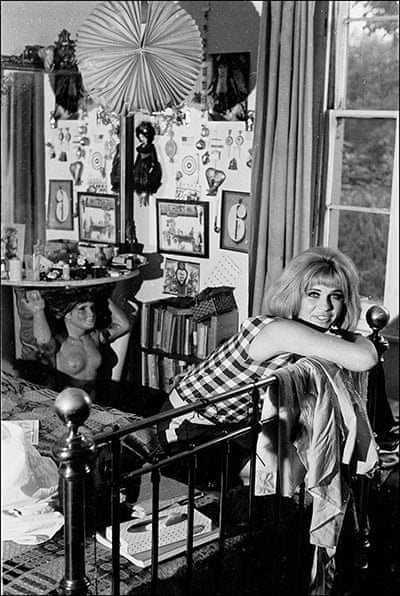

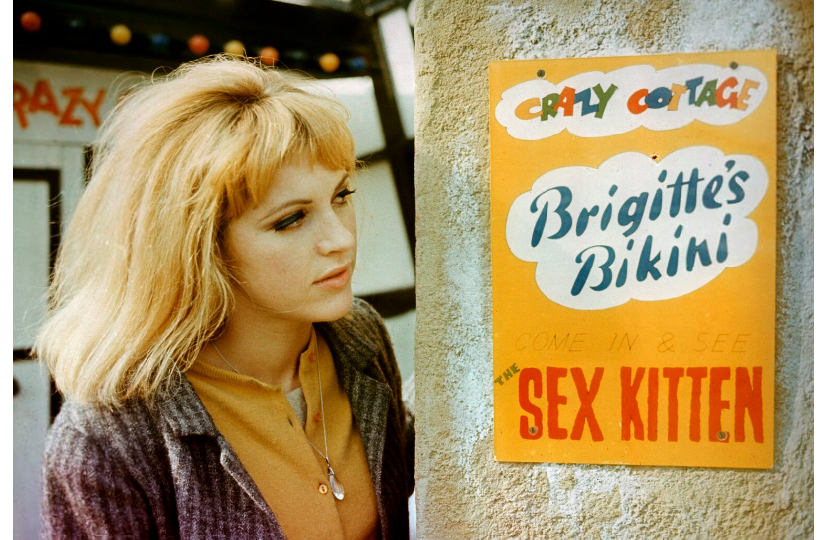

Pauline Boty, 1962. Photo: Michael Seymour. Source: www.npg.org.uk

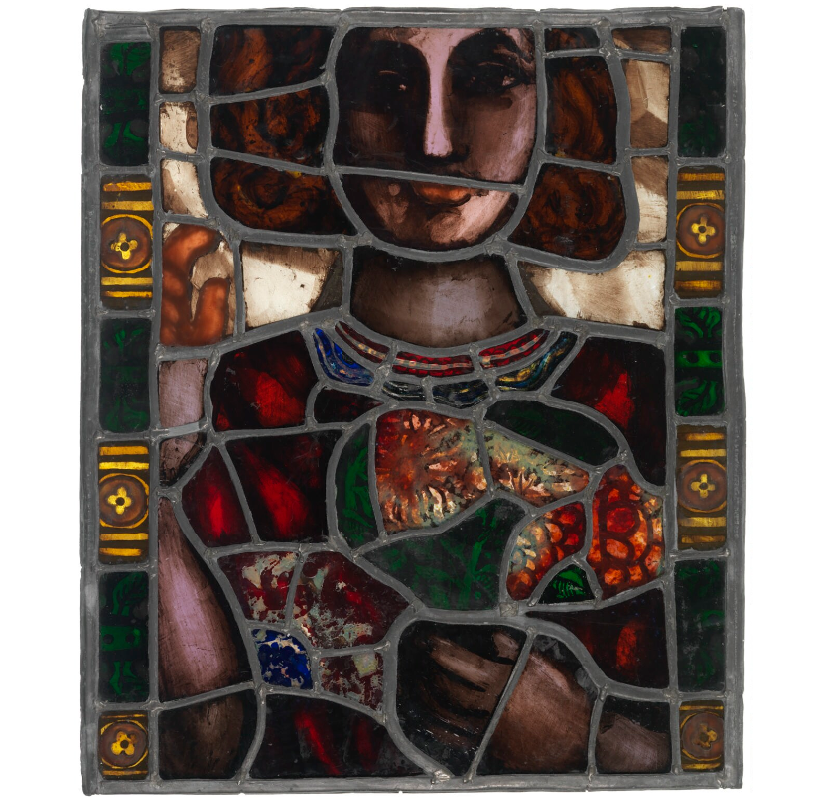

Time of glasswork

Pauline didn’t care that the access to the painting department was denied to her. At Wimbledon College, girls were strongly encouraged to choose stained glass department. They talked a lot about her, in whispers and aloud, they had head over heels in love with her, they called her the Wimbledon Bardot. Beautiful, daring, smart, confident. Pauline reads non-stop, listens to conversations and gets into arguments. For four years, she has been putting together fancy stained-glass windows, joining fragments and already seeing her future through these multi-coloured glasses. It is the stained glass technique that inspires her to experiment with pictorial collages, and these daring experiments are to be supported by one of her teachers. She is predicted to have a great future, they believe in her, she has temperament and talent, support and an inspiring environment.In 1958, Pauline Boty goes to study at the Royal College of Art and receives a scholarship. In the old college building, neither the architects nor the administration provided separate women’s toilets. Fine arts and art schools were still a man’s world. Even in the stained-glass department (yes, here the girls were also strongly advised to do stained glass) studied 28 male students and only 8 females. In college, Pauline works with glass again, while at home in the evenings she had time for painting.

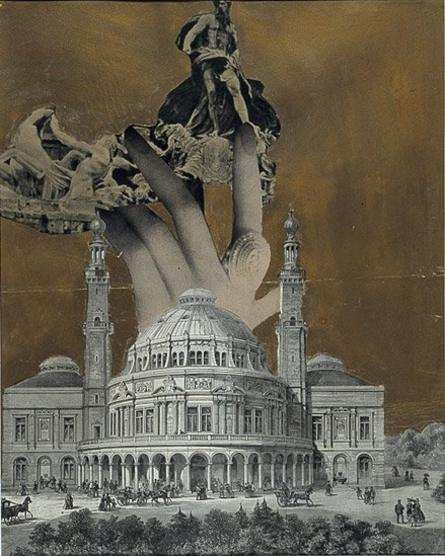

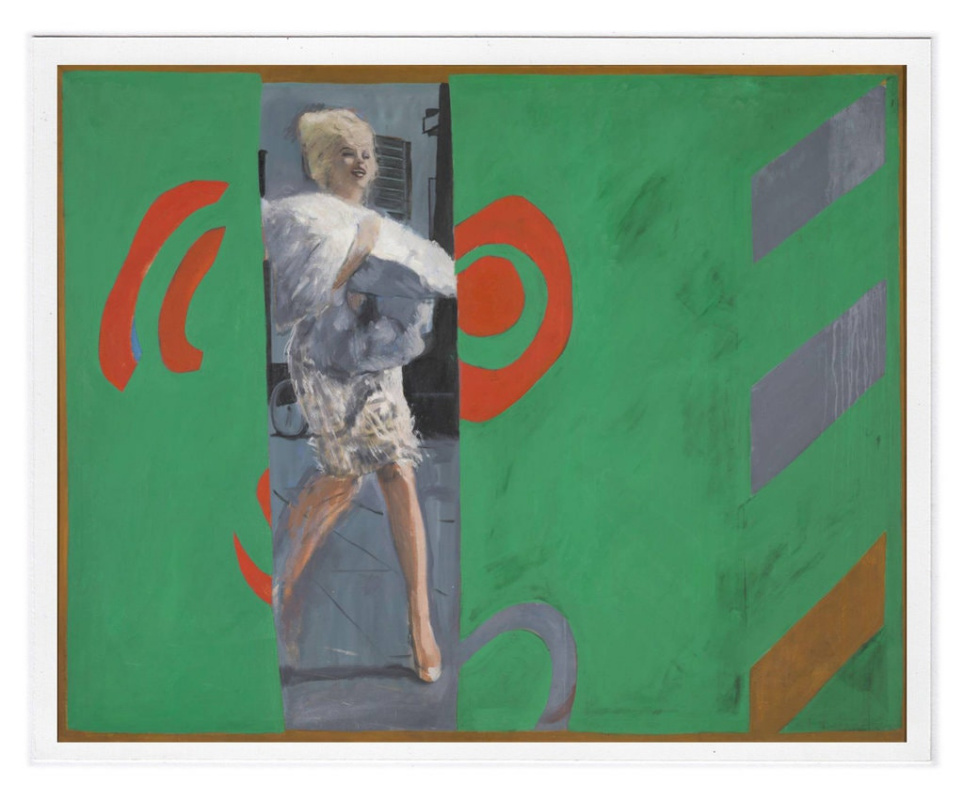

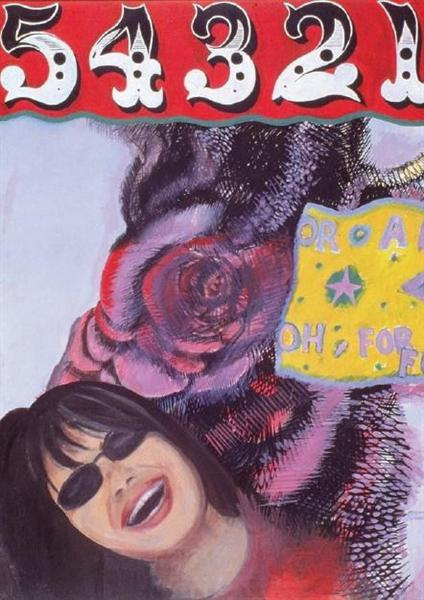

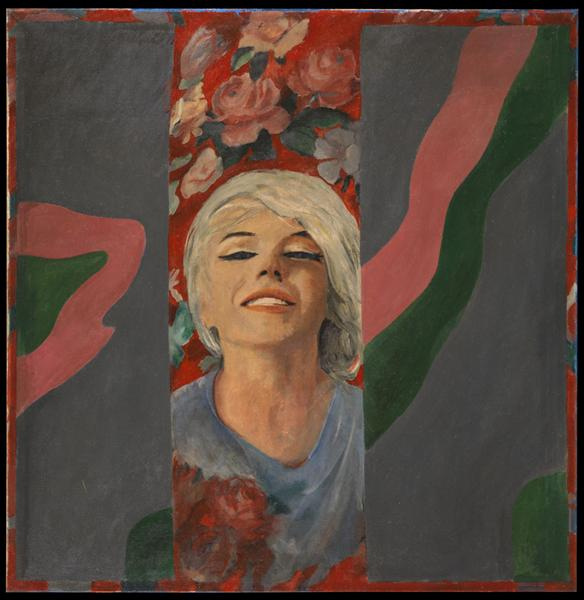

She worked all the time, moving towards her own style: she combined images of architectural structures, glamorous pop idols, abstract elements. In her first year in London, she already declared herself as a serious artist — three of her works had been accepted for the prestigious Young Contemporaries exhibition.

Everyone at the Royal College was in love with her. A College student, the future famous pop artist and Boty’s close friend Peter Blake (author of the cover for The Beatles' "Sergeant Pepper" — ed.) was stroken to his very heart. He said: "She had only one flaw. She was not in love with me." After some time, Boty told writer and playwright Nell Dunn: "I've never had a problem with men’s attention. I am lucky, I seem quite attractive to them, because I have a set of rather sexy qualities. But this admiration was always mixed with something like: ah, this happy dumb blonde! Well, you understand."

She worked all the time, moving towards her own style: she combined images of architectural structures, glamorous pop idols, abstract elements. In her first year in London, she already declared herself as a serious artist — three of her works had been accepted for the prestigious Young Contemporaries exhibition.

Everyone at the Royal College was in love with her. A College student, the future famous pop artist and Boty’s close friend Peter Blake (author of the cover for The Beatles' "Sergeant Pepper" — ed.) was stroken to his very heart. He said: "She had only one flaw. She was not in love with me." After some time, Boty told writer and playwright Nell Dunn: "I've never had a problem with men’s attention. I am lucky, I seem quite attractive to them, because I have a set of rather sexy qualities. But this admiration was always mixed with something like: ah, this happy dumb blonde! Well, you understand."

In the year of her graduation, 1961, Pauline already participated in a serious group exhibition. It was called Blake Boty Porter Reeve, after the names of the four members. Pauline was the only woman in this exhibition, the only woman in British pop art, one of the few women in British art. The world outside college was still a man’s world. And yet it was a wonderful world.

Nostalgia for now

Glossy Vogue and Elle, films by Bergman and Antonioni, tanned Jean-Paul Belmondo and white-skinned Marilyn Monroe, radio interviews and experimental theatre, Elvis and The Beatles, space exploration and advertising, comics and youth protests, miniskirts and bright shirts, smoky dance halls, coffee, marijuana and wine, bright packaging, mass production. All this poured into England, a country where the rationing system and product distribution control were only finally abolished in 1954. Pauline Boty called her art "nostalgia for now":"This is akin to depicting mythological subjects. Film stars… are the 20th century gods and goddesses. People need them, and the myths that surround them, because their own lives are enriched by them. Pop Art colours those myths."

Pauline is in the thick of things: she is an actress, a radio presenter, an artist, a dancer. She is wearing Levi’s 501, books by Camus, Sartre, Proust, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche are at her bedside. On the wall of her tiny room in Notting Hill, London’s most artistic quarter, there’s a pop-art iconostasis. Portraits of Elvis and Monroe next to African art objects and reproductions of Botticelli and Renoir, photographs of movie stars and young white-toothed politicians cut from magazines, engravings of Parisian squares and Rococo ladies, pictures of Italian cathedrals and black musicians, modern fashionistas on bicycles and heels.

Newspapers wrote about Pauline: "Actresses often have tiny brains. Painters often have large beards. Imagine a brainy actress who is also a painter and also a blonde, and you have Pauline Boty." Since 1962, photographers of important metropolitan magazines and newspapers have been queuing up in her studio — and Pauline posed generously, always next to her paintings: in heels, in underwear and an unbuttoned shirt, without underwear and in a wide Hemingway sweater, hat and sunglasses, she repeated the poses, outfits and smiles of her paintings' subjects. She became one of them herself. An icon, a legend, a star. However, magazine photographers afterwards scaled the photos, cropped the pictures, and left only a spectacular blonde in lingerie.

The BBC host of The Public Ear, Pauline interviews The Beatles for the first time, months before their worldwide fame begins. Little-known Bob Dylan dedicates a song to her. In Alfie movie, young Michael Caine kisses Pauline among the long dry-cleaning hangers in a tiny 11-second sequence. Every day she wanders the streets in search of entertaining trash — bright labels, cigarette packs, flyers. In the street markets, she looks for lace trimmings and magazine filings. They called her "domesticated Dada". Every day she eagerly works on canvases, which she fills with today’s images and dreams, attaching every minute artifacts here and there, which would have become trash tomorrow. She greets every day with joy, and sees it off with longing and nostalgia. Because it never happens again.

The BBC host of The Public Ear, Pauline interviews The Beatles for the first time, months before their worldwide fame begins. Little-known Bob Dylan dedicates a song to her. In Alfie movie, young Michael Caine kisses Pauline among the long dry-cleaning hangers in a tiny 11-second sequence. Every day she wanders the streets in search of entertaining trash — bright labels, cigarette packs, flyers. In the street markets, she looks for lace trimmings and magazine filings. They called her "domesticated Dada". Every day she eagerly works on canvases, which she fills with today’s images and dreams, attaching every minute artifacts here and there, which would have become trash tomorrow. She greets every day with joy, and sees it off with longing and nostalgia. Because it never happens again.

5, 4, 3, 2, 1

1963

5, 4, 3, 2, 1…

Speaking on the radio, Pauline Boty announced the approaching revolution: "All over the country young girls are starting, shouting and shaking, and if they terrify you, they mean to and they are beginning to impress the world." She herself was getting the best at it. After a 10-day romance with literary agent Clive Goodwin, Pauline married him. She was happy and obsessed with work. He was the editor of a radical publication and a leftist ideologist. Thanks to him, a political context appeared in Boty’s paintings: the Cuban Revolution, the Vietnam War, the Kennedy assassination, the sex-political scandal with the military secretary John Profumo, which led to the resignation of the government and the defeat of the conservatives in the elections. Writers, artists and musicians gathered in Clive and Pauline’s apartment. Their happy life together seemed to be just beginning. They were full of energy, they had so many ideas.

Color her care

1963

In 1965, Pauline got pregnant, and was diagnosed with cancer during a routine pregnancy test. She is offered chemotherapy on one condition — an abortion. And Pauline refused. She decided to bear and give birth to the child.

Pauline Boty died four months after giving birth to her daughter. She was only 28 years old. For a while, friends wrote touching memories of Pauline, pulled themselves together after the shock, talked about a solo exhibition of the only pop artist in Great Britain. But life in swinging London rushed faster and faster, yesterday’s magazines flew into the trash cans, new movie posters were glued on top of old ones that had not yet turned yellow. The scale of the fame of the new stars seemed incredible: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Twiggy, Veruschka. The last person who could still save her work, the artist’s husband Clive Goodwin, died in a tragic and ugly situation in the middle of Los Angeles: they confused his haemorrhage with drunkenness and imprisoned him, so he spent his last hours in a jail. Pauline Boty was forgotten for several decades.

Her daughter, also an artist, died of an overdose at the same age as her mother had died. But she managed to tell one persistent curator that her mother’s paintings have not gone anywhere. They were kept in the most ordinary English house, on the farm of Pauline’s brother.

Pauline Boty died four months after giving birth to her daughter. She was only 28 years old. For a while, friends wrote touching memories of Pauline, pulled themselves together after the shock, talked about a solo exhibition of the only pop artist in Great Britain. But life in swinging London rushed faster and faster, yesterday’s magazines flew into the trash cans, new movie posters were glued on top of old ones that had not yet turned yellow. The scale of the fame of the new stars seemed incredible: The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Twiggy, Veruschka. The last person who could still save her work, the artist’s husband Clive Goodwin, died in a tragic and ugly situation in the middle of Los Angeles: they confused his haemorrhage with drunkenness and imprisoned him, so he spent his last hours in a jail. Pauline Boty was forgotten for several decades.

Her daughter, also an artist, died of an overdose at the same age as her mother had died. But she managed to tell one persistent curator that her mother’s paintings have not gone anywhere. They were kept in the most ordinary English house, on the farm of Pauline’s brother.

An ordinary English house

David Alan Mellor curated a gallery in the London Barbican in the 1980s, organized exhibitions and wrote books on British art of the 1960s. As a teenager, he saw Ken Russell’s Pop Goes The Easel movie about four young pop artists, and was blown away. Everyone knew about three of the artists (Peter Blake, Peter Phillips and Derek Boshier), whereas Pauline Boty, the only female artist in this company, was forgotten. It’s like she never existed. Not a single her picture in the galleries, not a single worth mentioning in books or articles.

Pauline Boty, 1962. Photo: Michael Seymour. Source: www.npg.org.uk

The search led Mellor to a farm in Kent, where the most important paintings by Pauline Boty, which he had only seen in black and white photographs and in a single black and white film so far, were stored in a neat pile in a utility shed. An ordinary English house, in which they did not really understand what to do with all these roses, seductive female torsos, hands and respectable men, recognizable smiles of movie stars, symbols of a time that is long gone. When Mellor pulled out the first painting "It's A Man’s World" from the stack of canvases, he burst into tears.

In 1993, the Barbican hosted the The Sixties Art Scene in London exhibition, where Boty’s paintings took their place. Mellor curated the exhibition. Soon, violent verbal battles unfolded in British TV studios and live broadcasts, where some famous art critics argued about the empty-headed cute doll who painted bad pictures with others who considered Boty an important figure in the history of British art. The fight subsided, and those several dozen paintings that were found on the farm of Pauline’s brother and in some London apartments storerooms, ended up in galleries and auctions. In 2017, "BUM", the last painting by Boty which she painted shortly before her death, was sold at Christie’s auction for 633 thousand pounds sterling, twice the estimate.

And in 2018, the Autumn novel by British writer Ali Smith was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Pauline Boty’s collages were at the centre of the lives and relationships of the book’s main characters. And then they finally learned about her all over the world. Now it can’t do without Boty.

And in 2018, the Autumn novel by British writer Ali Smith was shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Pauline Boty’s collages were at the centre of the lives and relationships of the book’s main characters. And then they finally learned about her all over the world. Now it can’t do without Boty.