log in

Enter site

Login to use Arthive functionality to the maximum

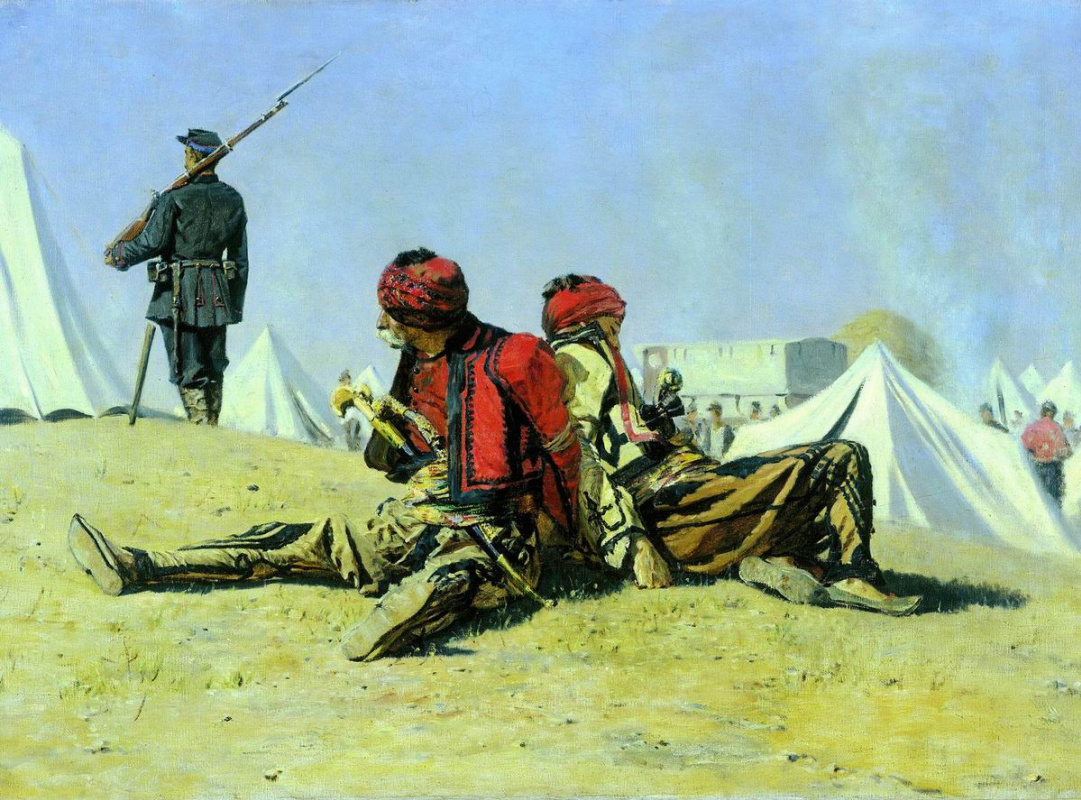

Two hawks (Bashibuzuki)

Vasily Vasilyevich Vereshchagin • Pittura, 1878, 78.5×110 cm

Descrizione del quadro «Two hawks (Bashibuzuki)»

In 1877, after learning of the beginning of the Russian-Turkish war, Vasily Vereshchagin left his Paris studio and went to the front. He was enrolled in the Danube army - without official content, but with the right of free movement in the army.

The result of Vereshchagin's participation in this campaign was the Balkan series - about 30 paintings, rightly considered the culmination of his work, a kind of dramatic peak. The Balkan series became a sensation: it was accompanied by a full house in Paris and London, 200 thousand people visited the exhibition in St. Petersburg.

Against the background of large, truly tragic cycle paintings (1, 2) "Bashibuzuki" are lost a little, they do not look so significant from the travel diary. However (almost always with Vereshchagin), and behind it is quite a dramatic story.

Once, two captured Albanian bashi-bazouks were brought to cavalry general Alexander Strukov. Vereshchagin offered to hang up the thugs right there without hesitation. Strukov replied that "in wartime, he does not like to hang them up, and he will not take these young men on his conscience." “What is it you Vasily Vasilyevich suddenly became so bloodthirsty? I did not know that for you, ”the general in turn asked. And Vereshchagin honestly replied that he had never seen a hang out and was very interested in the procedure. Later he asked the Albanians to hang up another general, who was familiar to him from the Turkestan campaign of Mikhail Skobelev, but he also refused.

Bashibuzuki were famous for their atrocities — professional thugs and marauders — they, according to the Bulgarians, “cut the babies out of their mother’s wombs.” Vereshchagin did not understand that the sentimental feeling did not allow the Russian generals to whip up Albanians at the nearest plane. He had to portray the "hawks" awaiting their fate.

This was the whole of Vereshchagin: for the sake of the sometimes unsightly truth, he did not spare either his enemies or himself. During the campaign, he risked his life more than once, participated in battles, was seriously wounded, but continued frantically drawing.

Once Vereshchagin's paints ran out, and he, after asking for permission from his superiors, went to Paris to pick them up. And barely returning - that's because good luck! - came under artillery shelling. The Turks bombed the barges along the bank of the Danube, and Vereshchagin went straight to one of them. After the shelling, fellow soldiers asked, how did he miss such a “gift presentation”? The artist replied that he saw everything better than others, because all this time he was directly under enemy fire. "Some simply did not believe", - he wrote in memoirs, - “Others considered this useless bravery. It never occurred to anyone that such observations constituted the purpose of my trip to the place of hostilities - if I had a box of paints with me, I would also have sketched several explosions. ”.

A curious detail: the truth-seeker Vereshchagin depicted bashi-bazouks with weapons sticking out of sashes. It is hard to believe that such dangerous prisoners were not disarmed before being delivered to the camp. It is even more surprising that the sentry has its back to the “hawks”, albeit bound, but still armed, the legends of which are desperate and bloodthirsty. It must be that the artist, who had a great weakness for ethnic color in general and weapons in particular, could not resist the temptation. He embellished the plot with the glitter of daggers, emphasized the danger of the characters. And maybe, even to some extent, he justified in his own eyes the desire to hang them in place.

With all his attention to detail, Vereshchagin was not a petty artist. The truth for him - an incorrigible battle-player - was not in the photographic reproduction of reality, but in depicting war as it is. With heroic pathos and quite prosaic details of army life. With courage and panic, pride and shame, with filth, cruelty, confusion, grief, blood and stench.

Such an approach earned him the fame of a “bad patriot” after the Turkestan series. The future emperor, the Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich, spoke of Vereshchagin, that "his ever-present tendentiousties are opposed to national pride." And the Balkan cycle did not add points to it in this sense.

The Russian-Turkish war broke down this seemingly iron man. During the storming of Plevna, the younger brother of the artist, Sergei, was killed. It affected the injury and accumulated fatigue. After finishing the cycle, he sworn to write "war paintings". "I am too close to my heart to take what I write, I cry out (literally) the grief of every wounded and dead person"- said Vereshchagin. His words of course he did not keep.

The result of Vereshchagin's participation in this campaign was the Balkan series - about 30 paintings, rightly considered the culmination of his work, a kind of dramatic peak. The Balkan series became a sensation: it was accompanied by a full house in Paris and London, 200 thousand people visited the exhibition in St. Petersburg.

Against the background of large, truly tragic cycle paintings (1, 2) "Bashibuzuki" are lost a little, they do not look so significant from the travel diary. However (almost always with Vereshchagin), and behind it is quite a dramatic story.

Once, two captured Albanian bashi-bazouks were brought to cavalry general Alexander Strukov. Vereshchagin offered to hang up the thugs right there without hesitation. Strukov replied that "in wartime, he does not like to hang them up, and he will not take these young men on his conscience." “What is it you Vasily Vasilyevich suddenly became so bloodthirsty? I did not know that for you, ”the general in turn asked. And Vereshchagin honestly replied that he had never seen a hang out and was very interested in the procedure. Later he asked the Albanians to hang up another general, who was familiar to him from the Turkestan campaign of Mikhail Skobelev, but he also refused.

Bashibuzuki were famous for their atrocities — professional thugs and marauders — they, according to the Bulgarians, “cut the babies out of their mother’s wombs.” Vereshchagin did not understand that the sentimental feeling did not allow the Russian generals to whip up Albanians at the nearest plane. He had to portray the "hawks" awaiting their fate.

This was the whole of Vereshchagin: for the sake of the sometimes unsightly truth, he did not spare either his enemies or himself. During the campaign, he risked his life more than once, participated in battles, was seriously wounded, but continued frantically drawing.

Once Vereshchagin's paints ran out, and he, after asking for permission from his superiors, went to Paris to pick them up. And barely returning - that's because good luck! - came under artillery shelling. The Turks bombed the barges along the bank of the Danube, and Vereshchagin went straight to one of them. After the shelling, fellow soldiers asked, how did he miss such a “gift presentation”? The artist replied that he saw everything better than others, because all this time he was directly under enemy fire. "Some simply did not believe", - he wrote in memoirs, - “Others considered this useless bravery. It never occurred to anyone that such observations constituted the purpose of my trip to the place of hostilities - if I had a box of paints with me, I would also have sketched several explosions. ”.

A curious detail: the truth-seeker Vereshchagin depicted bashi-bazouks with weapons sticking out of sashes. It is hard to believe that such dangerous prisoners were not disarmed before being delivered to the camp. It is even more surprising that the sentry has its back to the “hawks”, albeit bound, but still armed, the legends of which are desperate and bloodthirsty. It must be that the artist, who had a great weakness for ethnic color in general and weapons in particular, could not resist the temptation. He embellished the plot with the glitter of daggers, emphasized the danger of the characters. And maybe, even to some extent, he justified in his own eyes the desire to hang them in place.

With all his attention to detail, Vereshchagin was not a petty artist. The truth for him - an incorrigible battle-player - was not in the photographic reproduction of reality, but in depicting war as it is. With heroic pathos and quite prosaic details of army life. With courage and panic, pride and shame, with filth, cruelty, confusion, grief, blood and stench.

Such an approach earned him the fame of a “bad patriot” after the Turkestan series. The future emperor, the Grand Duke Alexander Alexandrovich, spoke of Vereshchagin, that "his ever-present tendentiousties are opposed to national pride." And the Balkan cycle did not add points to it in this sense.

The Russian-Turkish war broke down this seemingly iron man. During the storming of Plevna, the younger brother of the artist, Sergei, was killed. It affected the injury and accumulated fatigue. After finishing the cycle, he sworn to write "war paintings". "I am too close to my heart to take what I write, I cry out (literally) the grief of every wounded and dead person"- said Vereshchagin. His words of course he did not keep.