In our modern times, we try to record every precious moment of our lives on our gadgets, especially when it comes to our children and the important steps in their development. In the past, however, without the sophisticated devices, the artists preserved those moments by portraying their kids. In that manner, not only did they keep the sweet memory of infancy and the growing stages of their loved ones, but also made their characters infinite and immortal, as the youth itself possesses that feeling of boundless world and possibilities.

In the Rokoko era, in the midst of Versailles' pomp and profusion, and in close range of burgeoning French Revolution, Madame Vigée-Lebrun, who was a woman portraitist of the court ensemble, painted her self-portrait with her daughter. The painting, as most of her work, depicts an idyllic sight of a mother and a child, represented almost like angelic figures. The overall feeling, considering the historical circumstances, evokes the lull before the storm.

Self-portrait with daughter

1786, 84×105 cm

On the other side of the Channel, British painter John Hoppner, who was also close to high society, and even considered an illegitimate son of George III, quite often painted children’s portraits, as he was a father of five.

Here is the most famous of his children’s portraits, The Hoppner Children, dated 1791, showing them in a pastoral surrounding. The children are posing for their father, but also keeping the vivid movement of the juvenility.

Here is the most famous of his children’s portraits, The Hoppner Children, dated 1791, showing them in a pastoral surrounding. The children are posing for their father, but also keeping the vivid movement of the juvenility.

But things were about to change, as Europe after the Revolution turned away from the ideas of nobility and sentimentalism

, and cleared the path for the realistic, modern views on life. The art reflected the historical events, and even children’s portraits from now on depicted the relaxed, unimposed stand.

Sir John Everett Millais' portray of his daughter Effie, known as My First Sermon, 1863, reveals a young girl, dressed up in a red cloak and furry muff, trying to keep her seriousness, coping with fear and boredom, at the same time. The child’s character became more human and down-to-earth, differing significantly from chubby angels from the previous era.

My first sermon

1863, 92×77 cm

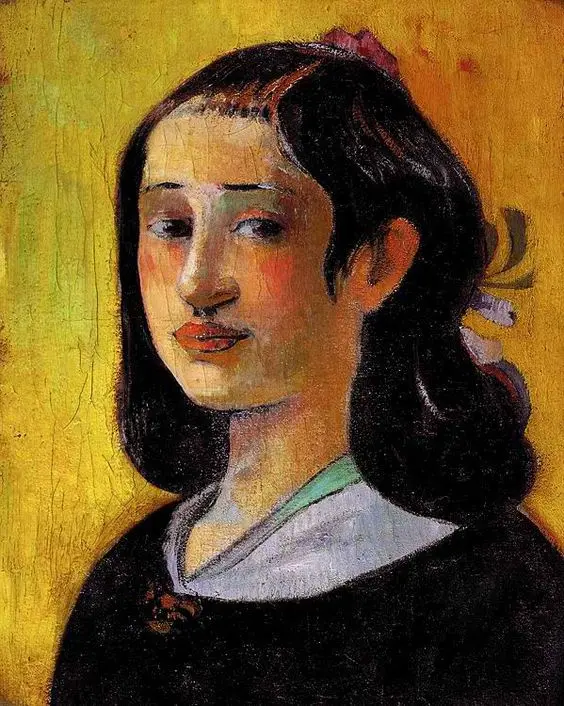

Aline Gauguin, Paul Gauguin’s beloved daughter, served as a model for a couple of portraits since she was still a toddler. Aline died very young, as a teenager, and the news of her death caught Gauguin in Tahiti. It is believed that a few months later Gauguin attempted suicide by drinking arsenic. The frequency of the portraits could suggest the longing to see the child — Gauguin was an infamous drinker and vagabond, away from his family who stayed in Copenhagen. But it can also be an apprehension of her close departure. In that way, the child was saved for eternity.

Paul Gauguin.

Portrait Of (daughter) Aline Gauguin

Paul Gauguin — Aline Gauguin and One of Her Brothers 1883

A grown-up, red hair girl in Berthe Morisot painting is her own daughter, Julie, from Morisot marriage to Edouard Manet’s brother Eugene. Julie posed for her mother and her famous uncle, as well as for Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Berthe Morisot. Julie Daydreaming. 1894.

Berthe Morisot. Julie Daydreaming. 1894.

Jean Monet on his Hobby Horse was painted by his father Claude Monet in the summer of 1872, in the garden of their home in Argenteuil. Jean was a subject for many of his father’s canvases, together with his mother Camille. The boy on his wooden horse was Monet’s favourite — he kept the painting for the rest of his life, protecting it from the public eye. Jean had a rough childhood, as he was born before Monet legally married Camille, and before Monet’s earnings were substantial enough to provide for his family. The portrait indicates an idealistic setting that Monet was now able to create for his loved ones.

The moving portrait of Pissarro’s daughter Jeanne-Rachel shows a fragile and beautiful little girl. But there’s a shade of grown-up melancholy within her eyes, in her portrait with flowers, even though the whole painting is exuberant with light and colours. The later portraits are darker, as the girl was becoming very ill from tuberculosis, an incurable disease at that time. Jean-Rachel died soon after the portrait on a stool holding a fan, at the tender age of 9.

"When I was still very little, three, four or five years old, my father did not tell me how I was to pose but took advantage of some occupation that seemed to keep me quiet," Jean Renoir, the prominent filmmaker later recalled.

Renoir was a kind and loving father, who let his sons play in his atelier, and had their lead soldiers collections all over the place. The warm colouring, the ripeness of the fruit that’s being shared among the children, brings the plain, intimate moment of pure and simple love. Renoir also kept the boys' hair long, because he enjoyed painting the gold hint of the restless locks.

Renoir was a kind and loving father, who let his sons play in his atelier, and had their lead soldiers collections all over the place. The warm colouring, the ripeness of the fruit that’s being shared among the children, brings the plain, intimate moment of pure and simple love. Renoir also kept the boys' hair long, because he enjoyed painting the gold hint of the restless locks.

Portrait of Jean Renoir and Gabrielle with her child

1894, 56×76 cm

When Edouard Manet married his former piano teacher and mistress Suzanne Leenhoff, she already had a child, a boy called Leon. Manet portrayed the boy many times, although he never legitimately recognised the child. The mystery was enhanced with the speculation that Manet’s father Auguste was actually the boy’s father. The crepuscular setting of the portrait Boy with a Sword evokes the old masters like Rembrandt and Caravaggio, with the enigmatic story behind it.

The portraits of children gradually became more realistic, bringing some complicated issues on the surface. The children were not restless, carefree creatures as they were on the paintings before. The life itself, with all its burden, left an indelible mark, and there was now a notice of entangled relationships among parents and children.

The portrait of Henri Matisse’s daughter Marguerite illustrates precocious girl, the one who grew up more quickly and took care of her father and domestical things. The heaviness in her looks brings the thought of troubles she later went through — during the World War II, she was sent to German concentration camp, yet, by some miracle, she escaped and survived.

Pablo Picasso’s brilliant mind and skills are well-known facts, but unfortunately, so is his problematic family context that continued even after his death. He tried to recreate the children’s manner of drawing, as he believed it is the simplest, yet the hardest thing to achieve. Naturally, he observed his own kids, played with them and painted them — but only while they were very young. Their adult lives and personas didn’t seem to raise interest in him, and all the connections to his children were abruptly cut off when they reached that certain age.

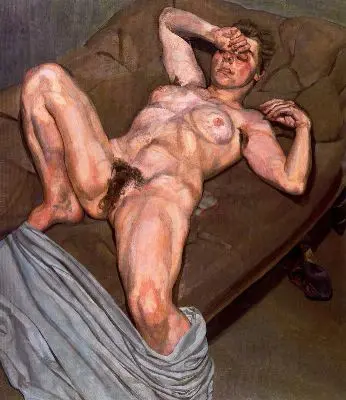

Rose, the study

of a nude body, emphasised the carneous sides of a human figure but it is actually a representation of Lucian Freud’s own daughter. The scandalous buzz that it caused was laughed away by this remarkable British artist, as provincial and philistine. His concerns were of the artistic nature only, and the detachment from the subjects, even if they were his own children, was evident. The depiction of nudity and profanity brings the reminiscence of Lucian Freud’s grandfather’s theories that only hidden agendas bear the danger of turning to impermissible and tabooed liaisons or madness.

Portrait Of Rose

Lucian Freud

Date: 1978 — 1979

Lucian Freud

Date: 1978 — 1979

But this bare and blatant sacrilege of the relationship that was held important for such a long time in human history, the one between parents and their brood, comes with the price. The freedom that it brought, and the boundaries that it took down, overthrew the basic feelings of plain love and care, in favour of the terms artist and his subjects.

Title illustration: Pablo Picasso. Maya in a Sailor Suit. 1938.

Telegraph Madame Guillotine National Gallery of Art

The Victorian Web Gauguin Gallery The Art Tribune The Met

It’s About Time blog MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE Globetrotter blog

The Met Henri-Matisse

Telegraph Madame Guillotine National Gallery of Art

The Victorian Web Gauguin Gallery The Art Tribune The Met

It’s About Time blog MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE Globetrotter blog

The Met Henri-Matisse