For some reason, it’s not customary to speak well of Picasso's first wife. Many of the artist’s friends openly disliked Olga Khoklova. And the artist himself caused a lot of brickbat. And Picasso’s biographers, who as a matter of fact knew about her only from the artist’s words, rarely graced Olga with serious attention. She was a ballerina, got married, gave birth to a son, lost her mind. But why did this woman attract Picasso? Was their family life unhappy from the very beginning? And how did Olga feel, watching Pablo change his mistresses, while remaining his legal wife until the end of her days?

Picasso came to Rome at the beginning of 1917 to relax and recover from love disappointments. In December 1915, his beloved Marcelle Humbert, known among the Parisian artists as Eva Gouel, died. He dedicated dozens of cubist paintings to her, entitled Ma jolie (My Beauty) and I love Eva. However, after her death, Picasso rather quickly pulled himself together, got into a new relationship and was even going to get married. But at the last moment his fiancée changed her mind. The 35-year-old artist was ready to settle down (at least, he thought so at the time) and have children. He needed peace and harmony, a "serene harbour" to heal his wounds. It was Olga Khoklova who became that "harbour" for Picasso.

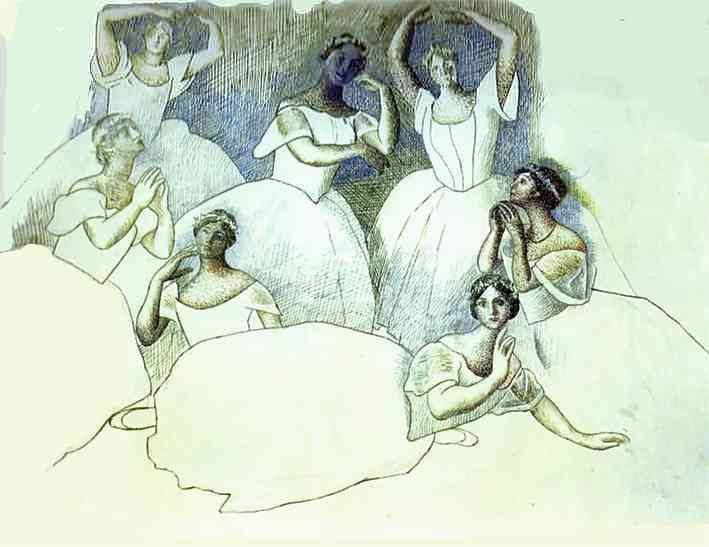

Olga Khoklova dancing

A girl from a good family

Olga was born on June 17, 1891 in the Ukrainian town of Nizhyn, into the family of Stepan Vasyliovych Khoklov, a colonel of the Imperial Army. The strict father did not approve of his daughter’s interest in ballet, but after the family moved to Kyiv, the girl’s mother Lidia began secretly taking Olga to classes. However, both parents didn’t want her to become a professional dancer. So, as soon as she got a chance, Olga ran away from them to Sergei Diaghilev. At the time of her acquaintance with Picasso, she had been dancing in the troupe for five years.There exist quite contradictory memories about Olga Khoklova’s professional abilities and appearance. Some ballerina declared that Olga was "nothing — nice but nothing. We couldn’t discover what Picasso saw in her." Some, on the contrary, compared her with the "Russian Madonnas". Olga was called a mediocre dancer, and Picasso’s beloved, Françoise Gilot wrote in her book about the artist that Diaghilev kept Khoklova in the troupe only because of her attractive appearance and noble origin. This is a very disputable statement, because Sergei Diaghilev, known for his captiousness and perfectionism, didn’t tolerate lack of talent and certainly would never let the untalented ballerina on stage just because of her good looks. It is known, however, that even if Olga wasn’t prima ballerina, she obviously had a certain amount of talent, good technique and a remarkable diligence.

A group of dancers

1920

Challenge accepted!

Picasso was elated at the prospect of leaving the war behind to spend a couple of months in the relative peace of Rome and started designing sets and costumes for Diaghilev’s Parade ballet. Picasso’s Cubist followers were horrified that their hero should desert them for the chic, elitist Ballets Russes, but he ignored their complaints. The artist had been dreaming of visiting Rome for a long time — he wanted to take his mind off the thoughts about whether he did the right thing when chosing life and art instead of war and probable death. Moreover, a new love appeared on the horizon.The first time he saw Olga, Pablo said with delight: "You look amazing." He started trying to charm and conquer the girl with all the strength of his hot Andalusian temperament. Although he courted her assiduously, the first surprise for Picasso was that Olga was too discreet and told the artist that he was compromising her with all that pressure. Olga proved adamantly chaste. Having noticed that the artist seriously became interested in Khoklova, Sergei Diaghilev warned him that a respectable Slav lady would not sacrifice her virginity unless assured of marriage. Well, for Picasso, it was just another challenge. Olga’s reserved character and restraint made him even more interested in her. He was even ready to marry, just to get that woman. In the end, he was going to settle down, so why not do it with her?

Pablo Picasso and Olga Khoklova in Rome, 1917.

The gala opening of Parade took place in Paris on May 18, 1917, at the Théâtre du Châtelet. Jean Cocteau, who also worked on the performance, then stated: "The audience wanted to kill us, women rushed at us armed with hatpins. A bayonet charge in Flanders [was] nothing compared to what happened that night at the Châtelet. Parade was the greatest battle of the war." This was nonsense invented by Cocteau to drum up publicity, which infuriated anyone who had suffered in the trenches. In fact, there were just a few boos during the premiere; applause prevailed.

Diaghilev’s company left Rome to perform in Barcelona. At that time, the matter of Pablo and Olga’s marriage was already settled, and the artist took his fiancée to meet his mother. Doña María gave the girl a warm welcome, visited her performances, but still saw it right to warn her: "You poor girl, you don’t know what you’re letting yourself in for. If I were a friend, I would tell you not to do it under any conditions. I don’t believe any woman would be happy with my son. He’s available for himself but for no one else." Being madly in love at that time, Olga was dead set on marriage.

Diaghilev’s company left Rome to perform in Barcelona. At that time, the matter of Pablo and Olga’s marriage was already settled, and the artist took his fiancée to meet his mother. Doña María gave the girl a warm welcome, visited her performances, but still saw it right to warn her: "You poor girl, you don’t know what you’re letting yourself in for. If I were a friend, I would tell you not to do it under any conditions. I don’t believe any woman would be happy with my son. He’s available for himself but for no one else." Being madly in love at that time, Olga was dead set on marriage.

Olga Khokhlova in Mantilla

1917, 64×53 cm

Pablo and Olga spent several months in Barcelona. They could not return to Paris, because Olga didn’t have a visa. When she was a member of Diaghilev’s ballet troupe, she could easily cross the borders, but at that time, she had difficulties obtaining documents. Olga was marooned in a country where few spoke French, let alone Russian. Picasso became for the girl almost the only point of support, especially when the Russian Revolution cut Khoklova off from her family. Her father and three brothers died, her mother and sister quickly moved to Georgia. Olga spent almost all the time with her fiancé, who constantly painted her, and even returned to the classical style of painting for the sake of his beloved, who wanted to recognize herself in the portraits. She finally allowed Picasso to sleep in her room. Diaghilev’s troupe went on tour to South America without her. Olga never took the stage again.

A different Olga

Originally scheduled for May 1918, the marriage had to be postponed. Olga had woken up one morning with an agonizing pain in her foot and could not get out of bed. She was obliged to undergo an operation, which left her leg encased in plaster till the end of June. At the wedding ceremony, which took place on July 12, the bride had to hobble around with a cane, and after a luncheon, returned to the clinic.The Picassos spent their honeymoon in Biarritz, where Olga was confined most of the time to an armchair or chaise longue. This is exactly how Picasso painted her: serious, melancholic, always a bit detached and never smiling. That is how she was seen and perceived by the public. That is how she was seen by Picasso’s friends, who took restraint for snobbery and haughtiness.

Olga and Pablo Picasso during their honeymoon. 1918

The first exhibition of works by Picasso, dedicated exclusively to Olga Khoklova, took place only in March 2017 at Paris’s Musée Picasso. And the visitors were extremely surprised when they saw a completely different Olga. The one, happily smiling in early photos, laughing and playing with the dogs in family videos filmed by Pablo. In one of them, Olga pulls the petals off a daisy — "he loves me; he loves me not". And in the picture taken by Picasso in his studio in the late 1920s, the artist’s slim and elegant wife is sitting in a chair against the background of a nude portrait of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Apparently, there was some kind of sadistic plan in it: to humiliate the annoying, unsuspecting wife by sitting her next to the desired lover.

Olga at Juan-Les-Pins, 1925.

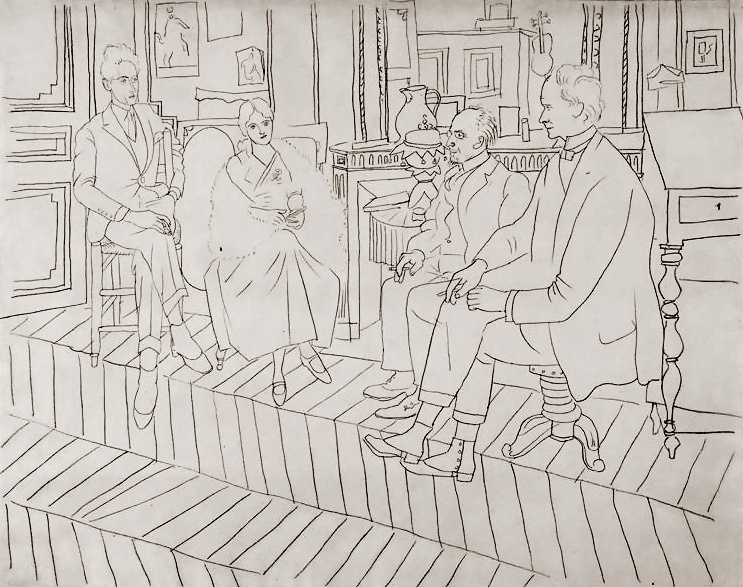

But it wouldn’t happen any time soon. In the meantime, the newlyweds, who returned from their honeymoon, settled in a luxurious apartment at Rue la Boétie. The Picassos' apartment consisted of a single, spacious floor divided into his and her realms. Olga furnished her (or rather, their) part elegantly and stylishly and kept things tidy there (scrupulousness was on the list of features the artist’s bohemian friends did not like about his wife). This is how Brassaï described their accommodation: "There was a large dining room with a round table extended with leaves in the middle of the room, a sideboard, and pedestal tables in every corner; a parlour, decorated all in white; and a bedroom with brass twin beds. No clutter, not a speck of dust. Polished, gleaming wood floors and furniture." Pablo domineered in the other part of the house: there was his workshop, in which reigned chaos, corresponding to the artist’s temperament. And by the way, it was there where Picasso kept a box with different things in memory of his first big love Fernande Olivier.

Picasso’s bohemian friends and colleagues criticized him for turning into a real bourgeois. Of course, it was his wife who was blamed for it. However, the artist himself willingly began to play the role of a respectable gentleman and a right-minded husband. He began to wear expensive suits, accompanied Olga at the balls, and received the Parisian beau-monde. And his former friends were, as they would say now, too "casual" and did not fit well into the interior of his living room.

Picasso’s bohemian friends and colleagues criticized him for turning into a real bourgeois. Of course, it was his wife who was blamed for it. However, the artist himself willingly began to play the role of a respectable gentleman and a right-minded husband. He began to wear expensive suits, accompanied Olga at the balls, and received the Parisian beau-monde. And his former friends were, as they would say now, too "casual" and did not fit well into the interior of his living room.

Olga and Pablo Picasso at the ball of Count Étienne de Beaumont, 1924

Declaration of Independence

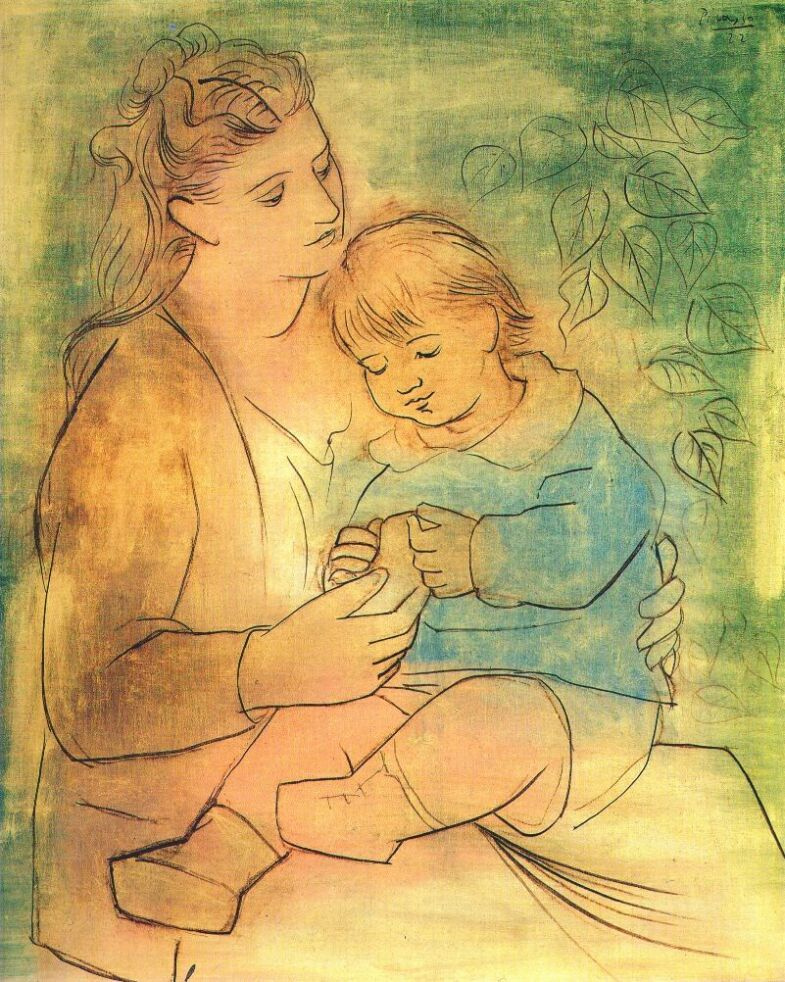

On February 4, 1921, Olga Picasso gave birth to a son who would be named Paul (Paulo). At first Picasso was delighted to have a son. Paintings and drawings of the baby in his mother’s arms testify to paternal pride and love. However, Olga became an obsessively overprotective parent, and, according to the biographer John Richardson, got into the role of the socialite, the wife of the world’s foremost painter, and now also the mother of the family. A bohemian at heart, Picasso would try to adjust to her notion of how a celebrated artist should live. He was proud of Olga and the ambience she provided, but this enjoyment would come under increasing attack from erstwhile friends. "You see, Olga likes tea, caviar, pastries, and so on," Picasso told one of his models. "Me, I like sausage and beans."

Mother and child

1922, 100.3×81.4 cm

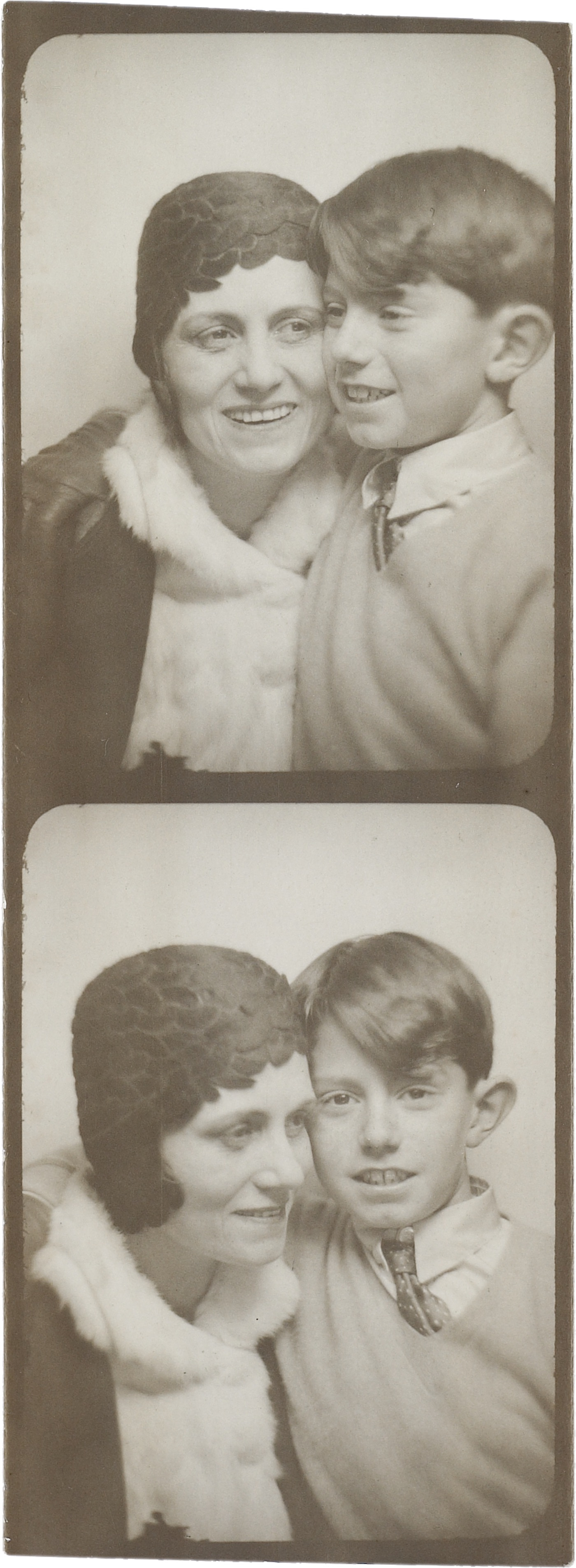

Olga and Paulo, 1928.

Family at sea

1922, 17×22 cm

In the summer of 1922, Olga fell seriously ill — it was seemingly the first manifestation of the gynaecological problems that would cloud the rest of her life. A sanguine drawing of Olga, done in September of that year, shows her looking haggard and sick. 41 years later, the artist, who superstitiously feared everything connected with illness and death, gave that drawing to his son Paulo for Christmas.

The Picassos continued being pillars of the Parisian beau monde. Countless dinners and social events worn Pablo down, but he used them to acquire useful acquaintances. At that time, Olga’s attitude to her son became another bone of contention between the spouses. The artist was not happy at the way she pampered and monitored the boy. Picasso’s constant irritation found a way out in his paintings. The Ingresque classicism would soon give way to a more revolutionary, more metamorphic style. At the end of the summer of 1923, the artist took possession of the floor above his apartment in Paris and was able to lead a much more independent life. No maids were allowed up there, and even Olga had to ask permission if she wanted to visit him. Picasso rarely visited home and resumed his old habit of visiting brothels.

The Picassos continued being pillars of the Parisian beau monde. Countless dinners and social events worn Pablo down, but he used them to acquire useful acquaintances. At that time, Olga’s attitude to her son became another bone of contention between the spouses. The artist was not happy at the way she pampered and monitored the boy. Picasso’s constant irritation found a way out in his paintings. The Ingresque classicism would soon give way to a more revolutionary, more metamorphic style. At the end of the summer of 1923, the artist took possession of the floor above his apartment in Paris and was able to lead a much more independent life. No maids were allowed up there, and even Olga had to ask permission if she wanted to visit him. Picasso rarely visited home and resumed his old habit of visiting brothels.

Passion and hate

The Picassos' marital life began to fall apart in 1927. In January, Pablo met the 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter. To conceal Marie-Thérèse from Olga, Picasso rented an apartment near where he had picked her up; to conceal her in his work, he was obliged to allegorize her in the form of a guitar, a jug or a fruit dish. He also filled several sketchbooks with erotic drawings. It should be noted that the artist lived under the same roof as his obsessively jealous wife Olga, who took the role of Madame Picasso — elegant consort, zealous mother, impeccable hostess — very much to heart. However, Pablo himself was not going to divorce. The guise of an exemplary family man served as his perfect cover.The artist soon found himself leading two separate lives, and this bifurcated pattern would be reflected in Picasso’s bifurcated imagery. Marie-Thérèse's images would be suffused with rampant sexuality, whereas those of Olga would reek of rage. But for quite a long time, Picasso managed to make sure that those parallel lives never met. Even when the artist was staying in Riviera with his family, he used every opportunity to visit Marie-Thérèse, whom he kept secreted in the pension nearby. During that vacation, Olga’s haemorrhages started up again, more seriously than ever, and she had to return to Paris, where she would undergo another operation. In total, she spent almost five months in the hospital, only occasionally returning home. All that time, Picasso could easily meet with Marie-Thérèse.

Corrida. The death of a woman bullfighter

1933, 21.7×27 cm

Of course, at some point, Olga figured out that she had a rival. And although she did not seem to perceive Marie-Thérèse as a serious threat to their marriage with Pablo, she also didn’t want to be humiliated. But his wife’s tears and exhortations caused only Picasso’s anger and remorse. In 1929, he created his Large Nude

in a Red Armchair. Without mentioning the name of the heroine directly, the artist put into his painting all his growing hatred for Olga. Broken limbs, mouth opened in agony… Unable to remove her from his life, Picasso used his canvas to mercilessly disfigure a woman whom he lovingly painted in another armchair only 10 years ago.

On the ruins of happiness

Supposedly, the scales did not fall from Olga’s eyes until Picasso’s major retrospective in 1932. Her husband’s passion for another woman appeared to her in its entirety — from one shameless picture to another. Amazingly, Olga continued living with Picasso. The last straw became Marie-Thérèse's pregnancy. Olga moved out of the apartment at Rue la Boétie, leaving it to her husband, and took Paulo to live with her. Later, Olga had her lawyer send an officer of the courts to make an inventory of her husband’s property. Picasso would never forgive her. He also didn’t agree to a divorce, because in that case, his wife would have gotten half of his paintings. Until the last day of her life, Olga remained Madame Picasso.Did Olga really lose her mind? There’s still no confirmation to that. One of Picasso’s biographers writes that Olga made a big mistake by giving everything she got to her inconstant husband. She devoted herself entirely to the family and made the interests of Picasso her life, and could not become independent. Disgraced and crushed, she was left completely alone. Even her favourite Paulo grew up to resent Olga and ultimately to loathe her, just like his father did. Olga desperately clung to happy moments from her past. That is why she followed Picasso on the streets, reminding him that they were still husband and wife in the eyes of God. That is why she wrote letters to him and sent him photographs of their son. That is why when Picasso moved to Cannes, she followed him, roaming from one hotel to another.

Pablo Picasso, Jacqueline Roque and Jean Cocteau at a bullfight, Vallauris, 1955.

In 1953, Olga became seriously ill. Cancer was eating her up slowly and painfully. She spent the last months in the hospital, begging each of her visitors to call for Pablo. The artist knew about it, but never visited his wife. Desperately holding onto the past, Olga recalled the days when she danced on the stage and dreamed of coming back to Russia. All Olga had kept was a steamer trunk chockablock with old costumes, empty perfume bottles, letters, and hundreds of photographs. She spent her last days frantically going through the things that reminded her of her lost happiness. Madame Picasso died on February 11, 1955.

Olga Khoklova in costume for the Shéhérazade ballet. Ca 1916.

P.S.

Pablo Picasso lived 18 years longer than his first wife. The artist once said: "When I die, it will be a shipwreck, and as when a huge ship sinks, many people all around will be sucked down with it."Françoise Gilot, who was lucky enough to survive in this shipwreck, gave perhaps the most accurate description of Picasso: "Pablo's many stories and reminiscences about Olga, Marie-Thérèse and Dora Maar, as well as their continuing presence just off stage in our life together, gradually made me realize that he had a kind of Bluebeard complex that made him want to cut off the heads of all the women he had collected in his little private museum. But he didn’t cut the heads entirely off. He preferred to have life go on and to have all those women who had shared his life at one moment or another still letting out little peeps and cries of joy or pain and making a few gestures like disjointed dolls, just to prove there was some life left in them, that it hung by a thread, and that he held the other end of the thread."